Nonprofits depend heavily on volunteer labor. In 2013, the value of volunteer labor was worth an estimated $163 billion, according to an Urban Institute report, with a labor equivalent of almost 5 million full-time workers.*

But free labor isn’t free of cost for organizations. Taking on volunteers “takes an investment of resources for the experience to be valuable” to both parties, said Mary Quirk, executive director of the Minnesota Association for Volunteer Administration (MAVA). She added that there is a misassumption “that organizations are standing ready and waiting for as many volunteers as possible.” That’s not always the case because supply and demand of both volunteers and opportunities “all need to be in sync.”

But volunteer habits have been shifting in response to economic, demographic and societal changes, according to Quirk and other nonprofit sources. Data suggest that volunteer participation has been in slow decline, and sources say the motivations and expectations of volunteers have evolved. All of these changes make the matching process more difficult and costly for nonprofits.

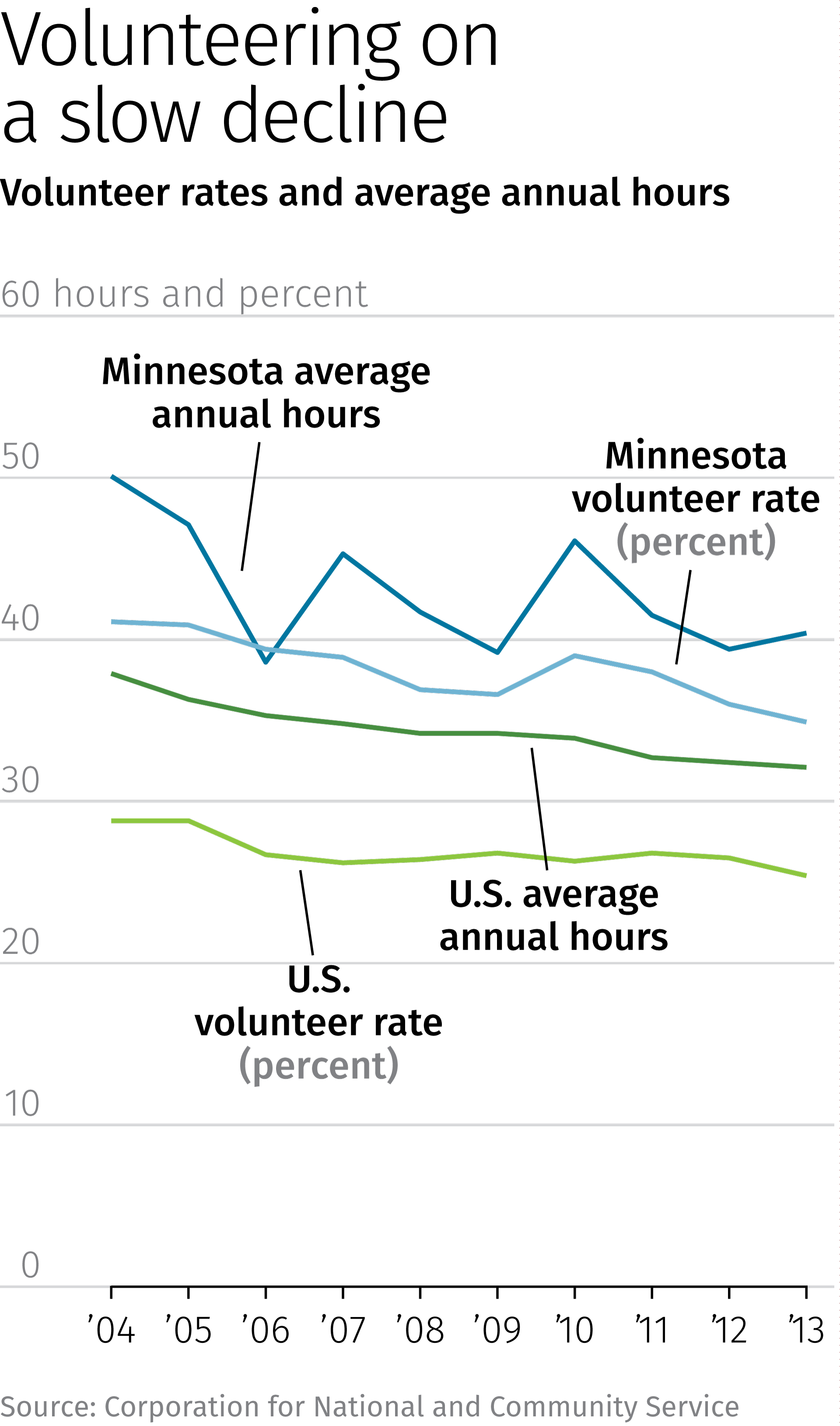

National data on volunteering from the federal Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) show a long-term downward trend in volunteer rates and average hours (see chart). Research by the Urban Institute, using self-reported data in the federal Current Population Survey, also found a decline—though much smaller—in volunteer rates and median hours from 2007 to 2013. (CPS data also suggest that average hours volunteered are several times higher than CNCS estimates.)

The good news is that volunteerism in all Ninth District states is consistently higher than the national average, according to CNCS data. For example, 35 percent of Minnesotans volunteer versus 25 percent nationally, and they donate an average of 40 hours annually versus 32 hours nationally.

Moreover, volunteering actually increased during the recession, both in the data and according to local sources. “It was almost a glut,” said Quirk. “Organizations had trouble placing all of their volunteers.” Some people volunteered in order to network for job leads, she said, “but some just had down time and wanted to do something good with their time.”

But local evidence concerning a longer-term drop in volunteerism is mixed. Most sources suggest that volunteerism declined as the economy improved after the recession, but that drop has not continued. For example, many nonprofits say they are relying more heavily on volunteers, which at least hints at greater volunteer availability.

MAVA has conducted a handful of surveys on the matter since 2010, and “we have pretty consistently found that half [of respondents] are seeing an increase in reliance on volunteers,” said Quirk. The main driver of the increase is financial pressure.

Some sources were not seeing much if any decline in volunteers. Renee Parker is executive director of the United Way of the Black Hills in South Dakota. “From our perspective, volunteering is getting better,” she said. “Nearly every day, we have people call us who want to do something meaningful. ... They want to know where the need is.” The organization’s board of directors has 35 people, “and there’s a waiting list.”

Changing of the guard

Rather than shrinking outright, sources said volunteering is changing, and that’s creating some tension in the mechanism matching prospective volunteers and organizations looking for nonpaid help.

Related content

All in the (nonprofit) family

The recession's effect on nonprofits was broad but uneven. With a return in giving, the sector's health has improved—but many challenges remain

The recession: Good for nonprofit employment?

Not all states are created equal when it comes to foundation giving

For example, the composition of volunteers changed as the recession eased. Today, the most volunteer inquiries come from students and interns who see volunteering “as a means for finding a job,” sometimes indirectly by networking with other volunteers, said Quirk. That was particularly the case in health care, which has seen an increase in volunteers. In a 2014 MAVA survey of volunteer programs in Minnesota, 45 percent of respondents reported seeing more inquiries from students and interns, the highest of any category.

There are geographic variations in volunteering trends. A 2012 MAVA survey of rural Minnesota nonprofits found that volunteer numbers actually rose for 41 percent of respondents, with only 12 percent seeing a decrease. But Quirk pointed out that even in rural areas, there are “haves and have-nots when it comes to volunteers.”

Half of the survey respondents said that older volunteers were no longer able to volunteer and that there was no one to replace them. In rural areas of western Minnesota, Quirk said, many communities had stagnant, aging populations. “Those places are having a lot of trouble recruiting [new] people. Everyone’s after the same volunteers.” Food shelves, for example, are having difficulty replacing a very loyal set of volunteers, many of whom have given their service over decades and are now in their 70s and 80s and unable to keep up the commitment, Quirk said.

But across the district, nonprofits are seeing changes in volunteerism driven by broad shifts in how households and families and individuals allocate their time. Volunteers are particularly hard to come by in the Bakken oil region, which stretches from North Dakota into the eastern edge of Montana, according to Liz Moore, executive director of the Montana Nonprofit Association. Here, the cost of living is so high that both parents often have to work and more seniors are working just to make ends meet. In both cases, volunteerism is undercut.

Parker, of the United Way of the Black Hills, acknowledged that while the organization has a healthy supply of volunteers, the makeup of those helpers is changing. “Younger people want to do a specific thing for a specific day,” she said. “They like the juicier projects where there is more networking and it’s more social. You have to make things fun.”

The stress of hectic work and home schedules is also affecting some potential volunteers. In the tourism-based economy of the Black Hills, many families “are working one, two, three jobs,” which makes it tougher to find the time to regularly volunteer, Parker said.

With busy work schedules, more people are also getting involved through their employers. In 1999, United Way hosted its first “Day of Caring” in Rapid City, which encouraged employers to let employees take time off work to volunteer. In the first year, all the volunteers fit on a small stage for a picture, according to Parker. This year, the event filled the Rushmore Center, one of the largest conference venues in the region, with attendance estimated at 1,200. “Employers are really supporting their employees to volunteer.”

The growth of this event and the preferences of young people are part of a general shift to more episodic volunteerism, often tied to specific events. A 2014 survey by MAVA found that 55 percent of nonprofits were seeing increased interest in short-term volunteering opportunities.

Earlier generations, said MAVA’s Quirk, “seem to be motivated to where the need was greatest, doing whatever was needed, and they were very loyal” to organizations and causes. Today, “more volunteers need to see impact [from their involvement] and more want to use their skill base” directly in their volunteer work. That shift has some upsides; for example, it gives organizations access to highly skilled individuals who would command high wages if they were hired for the same work. “Many want to share skills, and they have amazing skills,” said Quirk.

But matching those types of volunteers with the right opportunities is difficult, in part because of splintered communication channels. It’s no longer good enough to put an ad for volunteers on a website, or even in TV or newspaper ads. “The way people consume media today, you can’t put [volunteer opportunities] in one place” to reach potential volunteers. There are some online sites that match volunteers with opportunities, but even these aren’t much good “if volunteers don’t know they are out there.” To reach volunteers requires a more concerted, targeted effort, according to Quirk, but the time and money necessary are often scarce at nonprofits.

Many organizations also don’t need highly skilled volunteers. Instead, they need a steady supply of regular folks who will commit to getting the job done. “For many organizations, they have work set aside for volunteers to do, and they are having trouble finding volunteers to do the work they’ve always done,” Quirk said.

Note

* In this article, it is assumed that the vast majority of volunteering is for nonprofit organizations, including charities and noncharities.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.