In every community, there are families that everyone knows.

Consider your own hometown for a minute. Surely you know the NonProfit family. The NonProfit family is big and has been around for a long time. It has all types of individuals, oversized and undersized, young and old, and is spread wide.

In fact, you can find members of the NonProfit family in almost every community, even the smallest. It doesn’t matter what you need or have an interest in, you can find a partner in the NonProfit clan. Maybe you need help financially or spiritually, or are interested in political issues and current affairs, or the environment, or culture and the arts. Maybe you need help finding a job, or even just a square meal. Go find the NonProfit family—they are there to serve. You might even call it their mission.

Nationwide, nonprofit organizations play a significant but often underappreciated role in the lives of millions of people, delivering critical help to those in need, but also offering many other services that for-profit businesses and governments choose not to provide. From food shelves to discount clothing, matters of the body (health care) to those of the soul (religion), infants to elders, homeless shelters to housing associations, art museums to animal protection, local issues or international ones, it’s not an exaggeration that virtually everyone uses nonprofit services in some way.

But what happens when that support and service system becomes stressed, as it did during the Great Recession? The seminal economic event of this young century is often viewed from the perspective of for-profit businesses and government, the biggest players in the economy. But many nonprofits were also hit hard, including those that many lean on in tough times, and these organizations had to figure out a way to continue providing service—indeed, supply even more of it—while funding became shaky.

During the recession in Rapid City, S.D., “all the grant sources dried up, and at a time when the need was so high,” said Renee Parker, executive director of the United Way of the Black Hills. Organizations lost individual donors as well as larger foundation grants, she added, and government spending for nonprofit services also fell “and continues to stay fairly flat.”

Like the broader economy, the nonprofit sector appears healthier today, thanks mostly to a slow rebound in charitable giving, a push for more diverse revenue streams and greater collaboration born out of both need and opportunity. But challenges remain, including increasing demand for services, stiff competition for limited funding and changes in donor expectations and volunteer workforces.

First, the ugly

Like that of other sectors of the economy, the current state of nonprofits was heavily influenced by the Great Recession.

The nonprofit sector was put under stress virtually across the board, regardless of mission, because major funding sources—government, individuals and foundations—were themselves stressed. While some organizations suffered funding cuts, many serving the poor also had to cope with a rise in demand.

Related content

The recession: Good for nonprofit employment?

Not all states are created equal when it comes to foundation giving

Organize it, and they will come?

Nonprofits dealing with shifts in volunteering

“Without question, the recession had a tremendous negative effect on many nonprofits in the Upper Peninsula,” said Gary LaPlant, executive director of the Community Foundation of the Upper Peninsula, located in Escanaba, Mich. “The local community action agency was swamped with requests from seniors who couldn’t pay their heat or water bills. The local St. Vincent de Paul and Salvation Army food kitchens and food pantries saw huge increases in the number of people served.”

On the revenue side, he said, “gifts were more infrequent and in most cases smaller, and requests for grants and services were increased by a very considerable amount.” In 2011, nonprofits in Michigan also absorbed a double whammy when state lawmakers eliminated income tax credits for most charitable contributions, which LaPlant said “was quite devastating.”

In northeastern Minnesota, food shelves and homeless shelters “tried to cope with an unprecedented swell in demand. ... Individuals and families that had never before accessed services were turning to nonprofit and/or government assistance,” according to Tony Sertich, president of the Northland Foundation, located in Duluth, Minn. “At the same time, there were deep cuts to state and federal funding” which affected organizations serving those most in need.

In La Crosse, Wis., “nonprofits were stressed to just continue their missions,” said Sheila Garrity, executive director of the La Crosse Community Foundation, which saw time-consuming grant appeals decline. “I think many were too swamped to generate grant requests.”

Across Montana, individuals “whittled down what they gave” during the recession, and grantmakers cut back funding to organizations to “single years rather than multiple years. [So] the ability to plan went away,” said Liz Moore, executive director of the Montana Nonprofit Association (MNA).

The slow recovery

The full effects of the recession on nonprofits are complex (see sidebar). But as was the case in the broader economy, the post-recession recovery for nonprofits was slow and uneven, mostly because of disruption to major funding streams.

Generally speaking, nonprofit revenue comes from a handful of sources (see Chart 1). The largest chunk of nonprofit revenue comes from fees charged to government and private entities for various services, much of it for health care and education.

Between grants and fees, nonprofits receive fully one-third of their funding from government, about $137 billion in 2012. That money was spread among 56,000 organizations nationwide, according to the Urban Institute (UI).

Government funding to nonprofits since the recession, however, reportedly has been slack, though there are scant spending data to verify the matter. Nearly half of nonprofits nationwide reported a decrease in federal revenue in 2012, and 43 percent experienced a drop in state funding, according to the UI report, adding that “nonprofit organizations in 2012 were still dealing with many of the same issues as in 2009.” Responses from Ninth District states were roughly on par with national figures. A national survey last year by the Nonprofit Finance Fund found that almost half of respondents reported a five-year decline in government funding.

That decline has left its mark on Ninth District nonprofits. In Rapid City, nonprofits addressing youth, mental health, domestic violence, substance abuse and other services have been affected, Parker said. While the dollar amounts of lost funding might not always seem large, “for them it was substantial. Those programs have really struggled.”

Kate Barr, head of the Nonprofits Assistance Fund in Minneapolis, said the social services sector “is still really playing catch-up” because of rising service demands and poor funding. Programs serving people with disabilities, for example, are seeing more clients, while funding—typically from federal and state governments—is not keeping pace. Because the service delivery model in most of these programs is very labor intensive, productivity and program efficiency gains over time tend to be very small, Barr said. “So the costs are not in balance with the resources.”

Sertich, from the Northland Foundation, said the erosion of public funding “continues to have a strong impact” in northeastern Minnesota. Programs serving children and youth lost significant operating funding from government, he said, and many organizations sought support from area grantmakers. But Sertich added that “the scale of support that the federal and state governments can provide is difficult to replace by local governments, philanthropy and community giving.”

A foundation of individuals

Compounding lagging government funding has been an apparently slow recovery of charitable donations from individuals and foundations.

The biggest pot of charitable giving comes from individuals. In Minnesota, individuals account for three-quarters of charitable contributions, according to the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits (MCN), and most states see relatively similar levels. As a result, said Sertich, in Duluth, “many nonprofits are looking to increase their individual giving programs, particularly those that have traditionally relied on public funding and contracts.”

But individual giving has been sluggish since the recession, at least according to some sources. Available data on charitable contributions are sparse, and not particularly timely. IRS tax returns through 2012 show that cash and noncash charitable contributions nationwide have grown modestly every year since the end of the recession, but remain below pre-recession levels on an inflation-adjusted basis (see Chart 2). In Minnesota, individual giving rebounded from $3.8 billion in 2009 to $4.1 billion by 2012. But giving remains well below the $4.4 billion peak in 2007 (see Chart 3).

To put increased individual giving in a broader context, a large proportion of total charitable giving—roughly one-third, according to Giving USA—goes to religious congregations. Many nonprofits see only modest support from John Q. Public, and going after individual donors—large or small—often involves big outlays of time and resources.

Nonetheless, the outlook for charitable giving among nonprofit groups might be described as cautiously sanguine. Charitable donations nationwide grew by 4.4 percent in 2013, according to Giving USA, the fourth consecutive year of increase since the end of the recession.

In the Rapid City region, the United Way’s donor campaign raised $2.4 million—the first increase going back to at least 2010, according to Parker. Though the increase was just $100,000 (about 4 percent), Parker said there is more optimism in the region, mostly due to a better economy.

“It’s much easier getting into workplace campaigns. Doors are much more open today,” said Parker. In the past, many employers wouldn’t allow United Way representatives to talk with workers about giving, which she understood. “How can they be expected to donate when these workers are getting pay cuts or reduced hours?” Parker said. “Everybody here says it feels different now.”

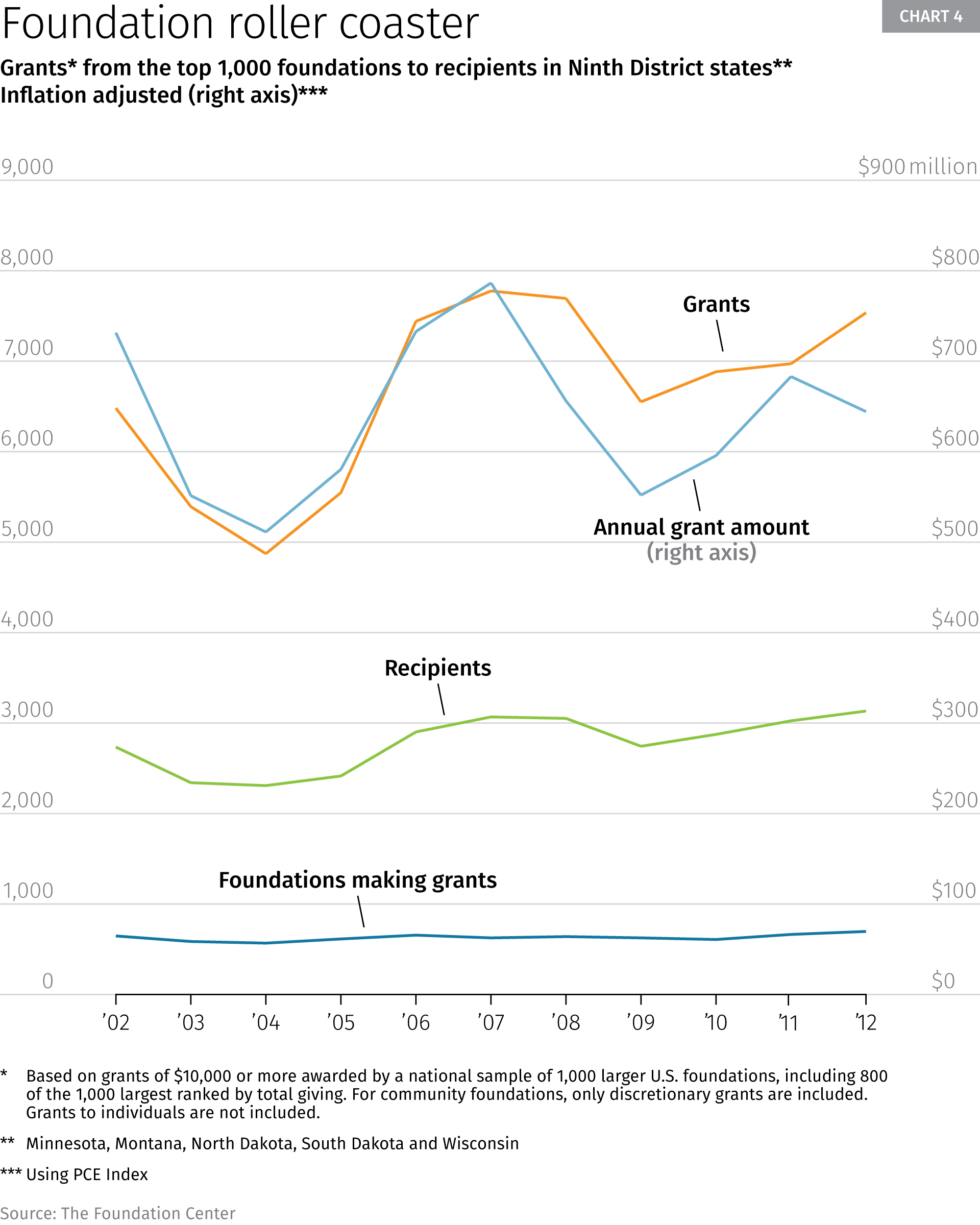

The other big source of nonprofit funding—foundation grants—is following a similar path in district states, according to the Foundation Center, a clearinghouse of philanthropic information. Giving by foundations typically is determined by their financial assets, which took a big hit in value during the recession, triggering a steep decline in overall grants from 2007 to 2009. While foundation grant funding appears to have recovered somewhat in Ninth District states, as of 2012 it remained below pre-recession levels (see Chart 4).

But Foundation Center data cover only 1,000 foundations nationwide, including 800 of the largest in the country. Minnesota alone has more than 1,500 foundations. As such, Foundation Center data arguably are a rough indicator of broad trends.

More comprehensive data from the Minnesota Council on Foundations (MCF) suggest that total corporate and foundation giving in that state did not dip much during the recession, and by 2012 was nearly 9 percent higher in real terms over pre-recession levels (see Chart 3). Unfortunately, similar data for other states aren’t available.

While foundation giving has increased in recent years, it hasn’t done so evenly among the many nonprofit sectors. The Foundation Center data suggest that arts and culture took the biggest funding hit from grantmakers (see Chart 5), and local sources said that is the case. Jon Pratt, executive director of MCN, said the sector experienced a sharp decline in giving, probably more than any other. The same was true in Montana, said Moore of MNA. “The thing that doesn’t get funded in Montana is the arts. ... Arts have been hit hard and have not come back.”

Many sources also noted that while foundation giving appeared to be returning, its emphasis has changed. Sertich, from the Northland Foundation in Duluth, said that “many foundations have recovered financially from the recession. However, there is a shift in the style of grantmaking resulting in ... more prescribed funding as foundations focus on specific types of issues and activities.”

This shift has affected general operating budgets the most. Maria Isley is head of the MCN branch office in Duluth. “Foundations are not giving for operating costs,” preferring to support bricks-and-mortar projects “versus keeping the lights on,” she said. “That’s been a tough thing. These organizations can’t function without operating funding.”

The change in funding approach shows up in the data, at least in Minnesota. According to annual giving reports by the MCF, grants for general support have been falling gradually as a share of total giving by foundations, from about 27 percent (the average from 2002 to 2005) to just 20 percent in 2012.

The same appears to be happening in other states. “Foundations have changed their criteria ... and are asking for more goal-oriented programs,” said Parker, in Rapid City. “They want innovative ideas to solve problems.” While logical and laudable on its face, not all new programs are better, Parker said, and they can pull resources from effective, long-running programs that “are not so jazzy.”

Parker and other sources also noted that funders increasingly believe that short-term funding should help make programs ultimately self-sustaining. But for programs serving troubled youth, domestic or substance abuse, the homeless and many other populations with ongoing needs, “those people can’t pay for services they are using so you’re always going to need those dollars. You have to pay for program services in an ongoing way,” said Parker.

No rest for the weary

In terms of future funding, nonprofits see an opportunity for windfall resources with the retirement of baby boomers and the subsequent transfer of generational wealth. As one source said, “That’s where the real money is.”

But even under the best assumptions—wealth transfers, higher government spending and a continued rebound of more traditional charitable giving—nonprofits aren’t likely to get much of a breather despite an improved economy because demand for nonprofit services has been rising, and that trend is likely to continue.

“The consensus among nonprofits is that the needs of people are much more complicated today,” said Sertich. “People are facing multiple, complicated issues such as mental health, substance abuse, low educational attainment, criminal record and so on. This makes helping them find economic security and stable housing difficult.”

According to a national survey last year by the Nonprofit Finance Fund, 80 percent of respondents reported an increase in service demands in 2013, the sixth straight annual increase; only 3 percent said demand decreased. Almost three in five respondents said their organization was unable to meet demand in 2013—the highest level in the survey’s history. Eighty-six percent expected demand to climb further in 2014.

All the while, donors will be asking for more tangible results and a closer accounting of spending. “One of the biggest challenges facing nonprofit organizations is their ability to demonstrate success and advancement of their missions,” said Judy Alnes, executive director of MAP for Nonprofits, located in St. Paul. “The contributing community wants results, and nonprofits need to make certain that they are both achieving results and measuring results.”

Some are struggling to make that adjustment, according to Alnes. “Many nonprofits in our communities are not organized for success. They operate as microorganisms and only chip away at the issues they aim to address.”

But many sources said the recession nonetheless had some beneficial—if unintended—consequences for the nonprofit sector as a whole. Barr said that the recession had a silver lining in that it forced organizations to identify their strengths and focus resources on their service mission. “There were a lot of hard decisions, but they were good decisions” about the best way forward, she said. “They really had no choice.”

Parker said that during the recession, “every agency was trying to fight for themselves” and their survival. Competition is still fierce for funding, “but people are joining hands and collaborating now” to provide service, she added. “We’ve seen great collaboration partly because they have to,” Parker said. When considering funding requests to the Black Hills United Way, Parker said, “if you are an organization that doesn’t play well with others, we don’t fund you.”

Diversify, and the hidden subsidy

The recession has also forced nonprofits to diversify their revenue—or else. “We’re seeing more organizations that have an earned-income component,” said Alnes, which gives organizations “less dependence on the vagaries of contributions. This makes it possible to exercise more self-determination” over what to do with revenue.

Nonprofits with retail lines like Goodwill-Easter Seals Minnesota, with its discount clothing and merchandise stores, have carved out successful revenue-raising niches to support their missions. From 2008 to 2013, the organization saw retail sales rise from $29 million to $67 million, according to its annual reports; net retail income, used to support the nonprofit’s mission of job training, placement and support, rose from $18 million to $35 million.

But retail enterprise is hardly a sure-fire approach to solvency. Many nonprofits that have historically depended on earned income—especially from sales of discretionary products or services such as admission tickets to the zoo or artistic performances—suffered considerably during the recession and are reportedly still playing catch-up.

Even for those able to make the necessary funding adjustments, sources said other organizational challenges exist. Several people noted that the implicit service contract with government had eroded and needs to be renegotiated.

“Generally, the trend has been to shift traditional government services to the private sector, mainly nonprofits,” said Sertich. “Early in this trend, 30 years ago, there was significant government funding to cover these costs. Over time, that funding has diminished.”

The good news, said Barr, is that “the charitable sector has risen to the occasion,” even during times of hardship. Nonprofits did “amazing things” to simply keep the doors open during the recession.

But she added that the nonprofit sector is starting to seriously grapple with the long-standing, hidden subsidies in many of its services—“where government underpays and gets a good deal,” thanks to either volunteer labor or underpaid staff at nonprofits. Many organizations are now dealing with shifts in volunteerism and difficulty attracting skilled professionals to lower-paying jobs, especially in light of rising student loan debt.

Eventually, Barr said, “the subsidy is not sustainable, and there comes a point where [an organization] can’t do it anymore.”

See the fedgazette article "Organize it, and they will come?" discussing volunteer trends among nonprofits in the Ninth District.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.