Video: fedgazette Editor Ron Wirtz on college finance

Many Americans hold a soft place in their heart for college. It’s a place for intellectual freedom, for expanding personal horizons, for gaining new friendships, experiences and perspectives.

Many Americans hold a soft place in their heart for college. It’s a place for intellectual freedom, for expanding personal horizons, for gaining new friendships, experiences and perspectives.

But many college-goers are ringing up a small fortune in debt, and a growing number of graduates across the Ninth District are earning a big, fat D—as in default—on their student loans, according to a fedgazette analysis of default rates at more than 250 public and private higher education institutions in district states.

Rising student debt and related defaults have been gaining national attention, in part through the Occupy Wall Street movement and its evolution. Facebook and other outlets are brimming with stories about students facing 5-, even 6-figure debts, accompanied by calls for loan forgiveness, temporary waivers for unemployed graduates and other efforts to address debt that OccupyStudentDebt.com says “is slowly suffocating us.”

Myriad factors influence student loan defaults in the short and long term. Two of the biggest causes behind the recent spike in defaults are rapidly rising student debt and a tough job market for graduates since the recession. Current default rates are also a fairly crude financial measure, and additional information about student borrowers suggests that their financial condition after graduation is worse than current default rates imply.

At the same time, default rates were much higher in the early 1990s, before changes made to the financial aid system helped to bring them down. Further changes made by Congress this time around should help struggling graduates. But rather than reducing incentives for schools and students to borrow (as in the 1990s), recent changes make it easier for borrowers to delay or dilute loan repayments on record-level debt. Though debt counseling and training in financial literacy have proven useful in helping borrowers to avoid delinquency, only strong job growth is likely to reverse the overall upward course of loan default rates.

The dog ate my payment

Student default rates are measured in cohort groups—in essence, the percentage of student borrowers due to begin repaying a federal loan during a federal fiscal year (Oct. 1 to Sept. 30) who default by the end of the following fiscal year. Borrowers who are more than 270 days delinquent by the end of the second fiscal year are considered in default unless special arrangements are made with the lender, which is fairly common. (This and other caveats to default rates are discussed later in this article and in the sidebar.) This official measure is called the 2-year cohort default rate.

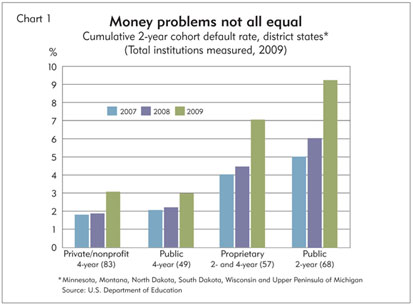

Virtually any way the data are sliced, default rates got significantly worse after the recession for the large majority of higher education institutions in Ninth District states (including those in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and all of Wisconsin). Though default rates vary considerably by institution type, the biggest increases were seen at public 2-year and for-profit schools of any program length, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education. But defaults also rose among public and private 4-year schools. (See Chart 1. These data concern only defaults on federal student loans; there are no public data on privately financed student loans.)

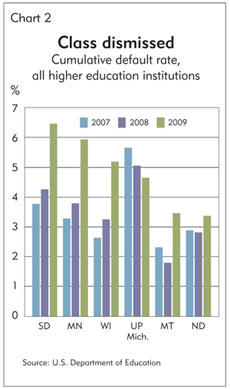

Neither is it a case of a few large schools running off the rails. Rather, increased default rates are widespread within institution types and sizes. For example, among 68 2-year public community and technical colleges in district states, only three saw default rates improve from 2007 to 2009 (the most recent data year available).Default rates for most district states (all schools, all borrowers entering repayment) have climbed significantly over this period (see Chart 2). The biggest exception to the overall rise is the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where student default rates actually declined. However, that region had comparatively high default rates to begin with and has just seven higher education institutions; four of them are 4-year institutions, which historically have had more stable default rates.

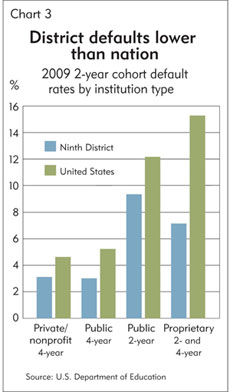

There is good news. Default rates in the district are generally—and significantly—lower than those for their national peers across institution types (see Chart 3). That’s particularly the case with proprietary (aka for-profit) schools, where the district default rate is about half the national rate and lower even than the district average for public 2-year schools.

Part of that advantage, however, is a quirk of data. Default rates are generally lower for 4-year programs offering bachelor’s degrees, and the district is home to a few 4-year, for-profit schools with a nationwide footprint whose respectable default rates are attributed solely to their home states. Minnesota, for example, is home to Walden University and Capella University, two online universities with tens of thousands of student borrowers throughout the country. The two schools had a total of 18,000 students begin repaying loans in 2009, and their combined default rate was less than 5 percent. All those borrowers were treated as though they attended college in Minnesota.

Pop quiz: Why?

Some of the culprits behind rising default rates are not particularly hard to identify. Like millions of other people, graduates are struggling to find jobs, and those are important as a means to pay off debt.

National American University (NAU) was founded in 1941 in Rapid City, S.D., and offers mostly secretarial and accounting classes. Today, the for-profit school offers a range of 2-year, 4-year and advanced degrees catering mostly to nontraditional, working adults (70 percent of them women), who can choose online courses or attend one of 35 campuses in 11 states, including 10 in South Dakota and Minnesota.

NAU’s default rate has typically been in the single digits, and it was 8.2 percent as recently as 2007. But the school’s default rate spiked to 14 percent by 2009. “The number one reason is the economy,” said Ron Shape, NAU chief executive officer. “There’s no doubt that plays a role here” because in a sluggish economy, graduates are not able to find jobs as quickly as they have in the past. Shape said that until recently, 92 percent of NAU students found jobs within five years of graduation. The 5-year job placement rate is now about 83 percent, “and it’s tied directly to the economy,” Shape said.

North Dakota is a good—if contrary—example of the relationship between economic performance and the ability to repay debt. With the economy booming, default rates at the state’s higher education institutions have risen only slightly of late (see Chart 2). At 3.4 percent, the Peace Garden State has the lowest statewide default rate in the district, and a sliver of the national rate of 8.9 percent.

The state’s handful of proprietary schools are a good example. Their cumulative default rate was 4.9 percent in 2009—one-third the national rate and well below the district average for such schools. Josef’s School of Hair Design is a for-profit vocational school with programs in cosmetology, skin aesthetics, massage therapy and nail technology. With locations in Fargo and Grand Forks, the school’s cumulative default rate was just 4.4 percent.

“There are more positions available than we have graduates,” said Heather Ostrowski, company recruiter and manager. And that’s despite strong growth in similar vocational schools in the eastern part of the state. “I think [graduates] can find jobs, and if not locally, then for certain in [other areas of] North Dakota.”

The connection between default rates and the job market is evident at many community colleges in other states. For example, annual job placement rates at Minneapolis Community and Technical College declined from 89 percent for 2007 graduates to 63 percent last year, according to Angela Christensen, MCTC financial aid director. Default rates rose by 50 percent from 2007 to 2009, to more than 12 percent.

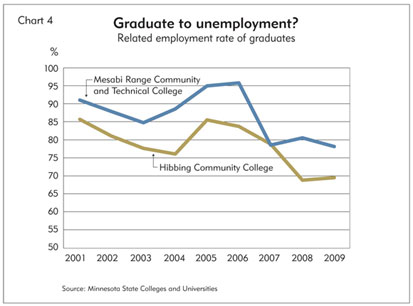

Hibbing Community College and Mesabi Range Community Technical College, located about 10 miles from each other on the Iron Range of northeastern Minnesota, have both watched default rates for graduates reach 15 percent and 16 percent, respectively, in 2009, while rates of employment related to graduates’ studies have fallen significantly, particularly since 2006 (see Chart 4), according to data from the Minnesota System of Colleges and Universities. (Financial aid officials at both schools declined to comment.)

It’s not just the economy, stupid

But there’s more to the default trend than a sputtering economy. In recent years, more students have taken out loans, and total debt levels have been ramping up to keep pace with steeply rising tuition. At 2-year public schools in Minnesota, the percentage of graduates incurring school-related debt rose from 54 percent in 2004 to 68 percent four years later, according to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study. Over the same period, median total debt rose 40 percent (inflation-adjusted) to $11,000.

Debt levels are heading further north. In 2008, Congress increased limits for federal student loans to keep up with the rising cost of going to college. Students have responded by significantly upping their borrowing. Among all undergraduate students attending Minnesota postsecondary institutions, borrowing from 2007 to 2009 increased by 39 percent (inflation-adjusted) to $1.54 billion, according to a 2010 report by the Minnesota Office of Higher Education (MOHE). The majority of those borrowers are still in school and have not yet entered repayment.

And unlike other holders of consumer debt, student debtors are on the hook indefinitely for those loans. “It’s extraordinarily difficult to discharge student loans in bankruptcy,” said Tricia Grimes, a policy analyst with MOHE.

Of course, higher debt would be manageable if wages for new graduates were increasing as well. But adding insult to a tough job search are stagnant wages for newly minted grads fortunate enough to find a job. A study of college graduates by Rutgers University last year found that wages for a nationally representative sample of college graduates in 2009 and 2010 were 10 percent lower than wages for graduates in 2006 and 2007. An analysis of entry-level wages for college graduates (using the Current Population Survey) by the Economic Policy Institute found that inflation-adjusted wages through 2010 had been flat for five years (and lower than wages in 2000).

As such, student borrowers have hit the trifecta of debt woes—students are more likely to take out loans and have higher debt, they’re having difficulty getting jobs and, even for those finding jobs, starting wages are not growing on pace with debt.

Default rates at Wisconsin’s 16 public technical colleges reached almost 10 percent in 2009, more than double the 2007 rate. Comparing the graduating classes from those years shows that 2009 grads found fewer jobs (86 percent compared with 93 percent), fewer found jobs in their field of study (73 percent to 77 percent) and median graduate wages had actually fallen by 13 cents per hour (to $14.46) after adjusting for inflation.

These data don’t count students who go to college but never graduate—unlucky winners of the double-whammy trifecta, if you will, because many of these students incur debt without earning the credentials that typically lead to higher-wage jobs (or any jobs) that help borrowers repay education loans. These students are particularly at risk for default. Though there are exceptions, college completion rates in the district have fortunately been moving in the right direction.

If you think this is bad...

Gauging the seriousness of this default trend depends a bit on the context. Current default rates are in many ways a poor measure of the financial health of students and their ability to repay education loans. More careful accounting suggests that student loan repayments are more troubling than current default rates imply (see sidebar).

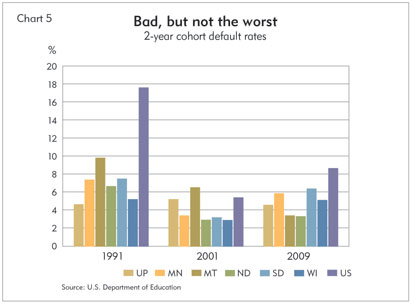

But it’s not as though student borrowers have broken through some fundamental, edge-of-the-abyss barrier for defaults. While rates have risen considerably, they are still well below rates of the early 1990s (see Chart 5). Rates as high as 20 percent were not uncommon, particularly among public and for-profit, 2-year institutions.

There are a number of reasons for the higher default rates back then, including much higher interest rates on loans. But a bigger reason is simply that they could be higher—there were no penalties on institutions whose students defaulted. That changed in 1991, when Congress required that colleges keep cohort default rates below a particular threshold—35 percent initially, 25 percent eventually. Failure to comply over a 3-year period meant their students would no longer be eligible for federal student aid. By 1997, more than 1,000 educational institutions nationwide had lost eligibility.

In the Ninth District, the Department of Education listed 333 colleges whose students were eligible for financial aid in 1991; by 2001, that number was down to 278, and in 2009 it was 257. The eliminated institutions were typically small, for-profit schools. Though default rates are rising today, all schools are a considerable distance from sanctions. In Minnesota, for example, the highest default rate in 2009 was 16.9 percent, at the Duluth Business University, a 4-year, for-profit school.

What, me worry?

The outlook on defaults is uncertain, because various factors could influence movement in either direction. Most sources agreed that faster economic (and thus job) growth is the best cure for ailing student borrowers. Said Grimes, at MOHE, “As the economy gets better, it would be surprising if rates didn’t settle down a little bit.”

On that front, things should get better, though not quickly or dramatically. In its annual forecast, the Minneapolis Fed predicted faster-than-average employment growth in 2012 across all district states, but unemployment is expected to decrease only moderately and remain above historical averages, in part because an improving economy is expected to pull more people who stopped looking for work back into the job market.

“Overall, I’m not very concerned about the cohort default rates,” said Mark Kantrowitz, a leading researcher on student debt and default, and founder of FinAid, an online resource for financial aid. “I expect them to start decreasing in a few years, especially as unemployment rates return to pre-credit-crisis norms over the next four years.”

In the near term, however, default rates are guaranteed to increase by bureaucratic quirk. That’s because starting in 2014, schools will be required to track 3-year cohort default rates, rather than the current standard of two years. That means default rates will rise almost by definition, and in most cases quite steeply. (See sidebar for more discussion and a 2-year versus 3-year cohort comparison of 2008 graduates.)

Interest rates are also a compounding factor. Rates on federal student loans were steadily lowered by Congress to 3.4 percent in response to the recession and slow recovery, but are scheduled to reset up to 6.8 percent for federal loans originated this summer unless Congress intervenes. Kantrowitz said that a 1 percent increase in the interest rate on a federal student loan corresponds to about a 5 percent increase in the monthly payment on a 10-year repayment term, and more as the loan term increases.

A penny borrowed...

Until the economy improves and job openings increase, many sources pointed to financial education as the best hedge against rising default rates. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of room for better grades in this department.

For example, Ostrowski, from Josef’s School of Hair Design, said it’s rare for prospective students to ask basic questions about average debt or starting wages. “It’s a very smart question,” said Ostrowski, who’s been at the school for 13 years. “I’m never asked that question.”

In a report last year on the financial outlook for private (nonfederal) student loans, Moody’s Investors Service projected future charge-off rates at more than 20 percent by 2014, in part because “there is increasing concern that many students may be getting their loans for the wrong reasons, or that borrowers—and lenders—have unrealistic expectations of borrowers’ future earnings. Unless students limit their debt burdens, choose fields of study that are in demand, and successfully complete their degrees on time, they will find themselves in worse financial positions.”

“The thing that bothers me is that some people are borrowing every penny they can” to support a certain lifestyle, said Grimes, “and then they are really surprised later” that they owe so much money. “Buyer beware has to enter at some point. … But I believe financial literacy is beginning to creep in.”

Montana offers a case study on how default rates can be corralled—at least to some degree—by lenders and higher education institutions. The state’s default rate increased only modestly in recent years. It was previously the district’s best at less than 2 percent and remains well less than half the national default rate.

“The secret to our success is fairly simple. We have committed significant resources in the form of employees who work with delinquent borrowers to keep them out of default,” said Bruce Marks, director of student financial services for the Montana Office of the Commissioner of Higher Education. “We believe that if we can talk to a borrower, we can keep that borrower from defaulting. … Individually contacting each delinquent borrower is expensive and time consuming, but we have done exactly that in recent years.”

That might sound like a simple bullet with too much silver in it, but financial counseling works. Kantrowitz, from FinAid, pointed out that many student borrowers are simply unaware of their options. Currently, borrowers can limit loan payments to 15 percent of their discretionary income, and all debt is forgiven after 25 years. Last year, Congress sweetened the terms even more, lowering the income-based payment to 10 percent and shortening loan forgiveness to 20 years, changes that are expected to go into effect this year.

The introduction of income-based repayment means “there’s absolutely no reason why anybody should default on their federal student loans,” said Kantrowitz. A borrower losing his or her job or earning less than 150 percent of the poverty line “has a zero monthly payment under income-based repayment. Yet borrowers still default on their federal loans. This demonstrates the need for improved communication with borrowers.”

Sources widely agreed that communication has to start when students first consider taking on education debt. According to Grimes, schools and aid programs are introducing financial literacy tools to make sure students understand what they are getting into when they take out loans.

But even then, a school’s hands can be tied if a student simply wants whatever federal loan money is available—money that comes without credit checks or other considerations. Aid formulas determine how much a student can borrow, and it might amount to several thousand dollars more than the student technically needs to cover tuition, books and other college expenses. But that extra money is hard for a student on a shoestring budget to turn down.

“If a check shows up in your mailbox for $2,500, would you send the check back, saying ‘I don’t want the excess money?’” asked Shape, from NAU.

He believes giving schools the ability to deny excess loan money would help in the fight against high loan debts and defaults. He added that getting students to borrow more frugally “would be the best option, but I don’t see it,” because students have gotten used to borrowing with few strings attached. “That train has left the station.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.