When it comes to student loans, “default” is a word with a simple meaning, but many social connotations. Technically speaking, default occurs when borrowers are more than 270 days late on their loan payments. But it carries many negative implications about financial responsibility and maturity.

It turns out that the measurement of student loan defaults is similarly nuanced. Even the term “default” is a bit misleading. Many assume it refers to people who have skipped out on their debt, or will eventually, as happens with personal bankruptcy.

But as many borrowers have come to learn, student loans (federal or private) are virtually impossible to discharge, even in bankruptcy. Funds for repayment can be garnished from the wages of student debtors and from Social Security benefits. Even long-term defaulters “pay something,” according to Tricia Grimes of the Minnesota Office of Higher Education. “If you earn some money, [lenders] are going to get some of it.”

So while virtually all student loans must be repaid, default rates tell us nothing about the state of student debt—whether, or how soon, borrowers will make good on repayment and to what extent taxpayers foot the bill for loans gone bad. Plenty of other caveats exist, suggesting that current default rates do not offer a very clear picture of the financial wherewithal of students after graduation.

For example, default rates reflect the repayment status only of federal student loans—those originated through either the Direct Loan or the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program (both administered through the U.S. Department of Education). A third source of loans is financed privately by financial institutions. These loans skyrocketed from about $6 billion in 2000 to $22 billion in 2007, or about one-quarter of all student loans that year. (Due to the recession, private lending pulled back to $6 billion in 2010, or less than 6 percent of all student loans.) These loans typically carry higher interest rates—a significant factor in monthly repayments. Students taking on private loans are also more likely to come from low-income families, go to a for-profit school and attend on a part-time basis—subgroups that tend to have higher-than-average default rates. Yet there are no default data on private student loans.

Current default rates also supposedly gauge repayments over two years, but that window is narrower than it might appear. The rate measures those entering repayment in one federal fiscal year (Oct. 1 to Sept. 30) and defaulting by the end of the following fiscal year. So ex-students entering repayment have just 12 to 24 months to fall more than 270 days (9 months) behind in loan repayments. So default rates capture loan performance of students who fall almost immediately and deeply into repayment problems.

Time out

Loan repayments typically start within six months of when a student graduates, has credit loads fall below required thresholds or drops out. But borrowers can postpone loan payments—through deferment or forbearance—based on economic hardship and other situations, such as continuation to graduate school. Though technically different, deferment and forbearance both provide relief from loan payments for up to several years. Once qualified, loans in defermentor forbearance are also considered current and thus counted (only) in the denominator of default rates, regardless of any underlying financial difficulty.

Surprisingly, very little is known about deferments and forbearance. The Department of Education publishes no public data on these categories, and institutional and other sources had little insight into the use of these tools over time.

A few studies shed some light on the matter. A July 2010 investigation of student loans by the Chronicle of Higher Education found that the percentage of those postponing their loan repayments grew from 10 percent in fiscal 1996 to 22 percent in fiscal 2007.

There are financial consequences to deferment and forbearance, because interest on outstanding debt continues to accrue on the loan balance for most loans in deferment or forbearance (the exception is for subsidized student loans in deferment). That typically adds up to thousands of dollars of additional debt—increasing the burden on students who delayed repayment because of financial hardship.

A study last year by the Institute for Higher Education Policy looked at a 4-year repayment window on 1.8 million FFEL loans originated in 2005. It found that 23 percent of borrowers used deferment or forbearance to avoid any delinquency on their loans. But another 21 percent became delinquent by 2009 and then applied for forbearance or deferment. Finally, 15 percent defaulted altogether by that year, and 4 percent were delinquent at some point but made payments to become current again on loans. Just 37 percent of borrowers managed to make timely payments without postponing payments or becoming delinquent or defaulting during the 4-year repayment period.

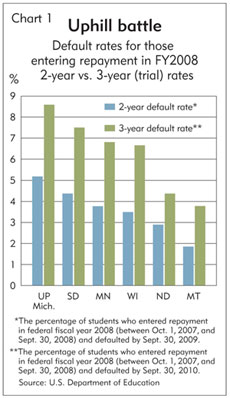

The widespread use of deferment and forbearance also means that the repayment performance of many student loans is effectively never measured because payments are postponed beyond the official 2-fiscal-years window. So in 2008, Congress responded by moving to a 3-year cohort rate, effectively extending the measurement window by an additional fiscal year. The new rates won’t have regulatory teeth in terms of student aid sanctions until fiscal year 2014, but preliminary data from the Department of Education show a big jump in default rates in the district. (See Chart 1; note that the comparison uses the 2008 cohort, because 3-year data are not yet available for the 2009 cohort.)

A lifetime of default

What happens to loans after this comparatively short—and early—repayment window is mostly guesswork. Unlike other consumer borrowers, a student’s likelihood of repaying an education loan actually goes up over time as he or she latches onto employment and builds a work history, which typically leads to higher wages in the long run.

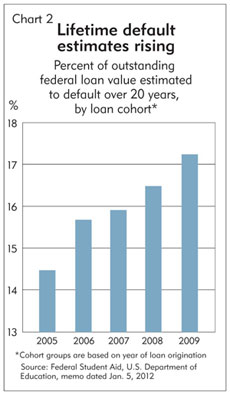

The Department of Education does not technically track lifetime default rates. But its Federal Student Aid office has started estimating a so-called budget lifetime default rate that reflects rates over a 20-year period for a particular pool of loans (based on when loans originate, rather than when they go into repayment). Not surprisingly, those estimates have been rising for recent loan cohorts (see Chart 2). Chronicle of Higher Education estimated in 2010 that one of every five government loans that entered repayment in 1995 had gone into default.

Critics of the current system say government should move away from nonpayment measures and instead track repayments, which would give policymakers a better idea of how many use financial aid as intended: Borrow money to go to college and improve skills, which should lead to a better job with higher income that makes it easier to repay loans.

In fact, a controversial pilot program that takes this approach was implemented last year. Congress imposed “gainful employment” regulations on for-profit schools intended to quash questionable recruiting practices by some schools and push institutions to pay more attention to job placement and wages earned after graduation.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.