Hey, buddy, can you spare a dime of credit?

Back in October and November, financial markets teetered as they haven't for decades. Urgent claims of a credit crunch—that credit was simply not available, except at scandalous rates—were rampant. Though evidence of an actual credit crunch was sketchy, bankers and businesses alike were feeling a bit of credit vertigo: Easy credit conditions were replaced by credit standards that better reflected borrower risk, a matter complicated by an economic slowdown that pulled the plug on demand and besmirched borrowers' credit ratings in the process.

Fast-forward six months—has anything changed?

To get a glimpse into credit conditions in the Ninth District ahead of the release of official data, in late April the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis conducted separate polls for financial institutions and businesses in the Ninth District. These are a follow-up to similar credit conditions polls conducted in November of last year (the results of which were published in the January 2009 fedgazette).

The results from the most recent polls show that credit conditions don't appear dramatically changed, save for the fact that people on both sides of credit transactions likely have a little better feel for and familiarity with the new credit environment. In general, credit volume to businesses and consumers continues to be weak, the result of tighter credit conditions and weaker credit quality among borrowers, but also because of weaker demand overall as borrowers wait out the recession.

Solitaire, anyone?

Banks and credit unions reported little problem with deposits; two of three respondents said insured deposits were up—about 20 percentage points higher than in the November poll. That finding jibes with national data showing a relatively sudden and positive shift in savings habits among U.S. consumers.

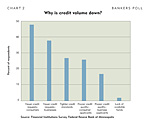

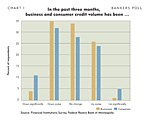

Despite the availability of credit, however, it's not flying out the door; over the previous three months, credit volume was down about 40 percent for both businesses and consumers (see Chart 1). A similar percentage of financial institutions said credit volume was down because both businesses and consumers were simply not seeking credit (see Chart 2). That's not particularly surprising given the depth of the recession to date, though not a lot of attention is paid to the demand side of this supposed credit crunch.

A small Montana bank with $9 million in assets said, "Our (customers) are very conservative and have stopped asking for money. We have money to loan and very few applications."

A Minnesota regional bank with $145 million in assets echoed that theme. "Businesses we talk to are laying low," reducing short-term spending and investments, "which reduces their interest in borrowing." Consumers are worried about their jobs and retirement nest eggs "and are not borrowing for consumption purposes."

Another Montana financial institution with $45 million in assets noted that it was not seeing a significant economic slowdown in its region, "but our volumes indicate (borrowers) are trying to save more and spend and borrow less."

For those seeking credit, many were less qualified to receive it: More than half of respondents said that credit quality for both business and consumer credit applicants had declined in the previous three months; about one in five attributed the decline in credit volume at least in part to the fact that applicants could no longer qualify for loans.

The trifecta for weaker credit demand stems from the fact that banks and credit unions have continued raising the bar to qualify for credit. Banks have been tightening their credit standards across the board, and for some time, according to various quarterly Federal Reserve polls. That appears to be continuing, according to this poll: Over the previous three months, almost 60 percent of respondents said collateral requirements rose, and 44 percent said they required more documentation for credit approval.

Overall credit quality at a small Minnesota bank was still good, according to an official, in part because "less stable borrowers are deferring large purchases that require credit. It appears the people who don't qualify know it and are deferring credit requests."

Businesses down in the credit mouth

The main themes coming from bankers were largely reinforced, and amplified in some cases, by district businesses, according to a second poll conducted in partnership with state chambers of commerce.

Forty percent of business respondents said their access to bank credit has tightened to some degree over the previous three months (see Chart 3). For those experiencing tighter credit, it manifested in several ways. For example, 59 percent said tighter credit came in the form of higher interest rates, almost half said their credit limits were lowered and about one-third said previously available credit was eliminated.

There were several reasons for tighter credit, according to business respondents. Almost 80 percent cited poor credit market conditions overall as a culprit. But about one-third acknowledged that credit had tightened as a result of their firm's own poor financial condition. As might be expected, tight credit was also affecting business operations. For those seeing tighter credit, 43 percent said they were curtailing capital expenditures and 31 percent said it would affect hiring decisions.

A Minnesota manufacturer with 45 employees said it was not having trouble getting credit—because it was simply not looking for any. "We actually do not need as much credit because we have stopped our capital investments, and we have stopped all unnecessary expenditures." That might not be good news to local bankers with cash to lend, but it has helped stabilize the company's financial position despite lower sales, an official reported.

Many businesses also deal with upstream and downstream credit markets—what nonbankers call suppliers and customers—and credit has been tightening there as well, according to the poll (see Chart 3). Close to half of business respondents said they have tightened credit to their customers and are doing so on multiple fronts, such as limiting new credit accounts, lowering credit ceilings and shortening pay periods.

A $65 million company in the oil and mining sector commented, "Customers want longer credit terms (and) suppliers want shorter terms. We are asking our suppliers and vendors for longer terms. All of our customers want price cuts of 10 to 30 percent, which is simply not realistic."

An official with a Minnesota manufacturer with $25 million in revenue said the firm was "very financially strong" and had very little debt. "This combination has allowed us to attract banks very willing to offer funding if we were to need it." At the same time, the company has had to take a "tougher stance" on credit to customers, stopping shipments for late payment and requiring advances from some customers that were in poor financial shape.

Firms in construction and manufacturing were most likely to report difficulties accessing credit. A $30 million commercial real estate firm with sales in three states said it "is virtually impossible for developers to get financing. We have a national client with a solid business that we cannot move forward with because money is not available to build their building."

And it's not hard to see how credit problems for some firms cascade into other ones. A construction firm with 500 employees and $75 million in sales in five district states and Iowa said its own access to credit "has not been impacted, but our customers' access has been impacted severely." The company lost several contracts totaling approximately $10 million last year "due to financing issues facing our customers."

In the end, a familiar commentary among bankers and businesses was the current lack of confidence in the economy, and the role confidence plays going forward regarding the supply of and demand for credit. Even in areas not feeling the economic pinch so much, "there is a hunker-down mentality," said a small North Dakota bank. "Although the local economy remains reasonably strong, uncertainty about the national economy is impacting both borrowers and lenders."

A larger Montana bank with about $350 million in assets noted that "borrowers are being more conservative and waiting to see how the recession plays out. Loan volume will come back when borrowers are more confident in the economy."

See description and methodology.

Bank Survey Summary [xls]

Business Survey Summary [xls]

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.