You might call it part of the underground economy: It doesn't deal drugs, but it helps those that are addicted to them.

You can also call it the middle-child economy, not getting much attention despite the fact that it employs close to one in 10 American workers and has annual revenue in the trillions. You might even nominate it as the nation's most productive sector, given its extensive use of free labor.

If you've ever been a Scout, belonged to a religious organization, listened to a live orchestra, had a baby; if you're a veteran; if you've volunteered or been a member of a local chamber of commerce—among many, many other things—then you've participated in the underappreciated economy of nonprofits.

Certainly, everyone's familiar with the nonprofit sector, thanks to the likes of the ubiquitous United Way and its network of charities. But you might be surprised to learn just how prevalent nonprofits are in today's society. More than half of the nation's hospitals, and almost half of its higher education institutions, are nonprofits, not to mention virtually all religious organizations and most museums, symphonies and membership associations in the United States. The sector also includes such niches as cemetery companies, co-ops to finance crop operations, mutual insurance companies, credit unions and public-employee pension funds.

We pay a lot of attention (with good reason) to the economic health of the private sector economy, as well as to the fiscal and political environment of government. But what of the nonprofit sector—what have you heard lately? Don't talk all at once now.

The collective blank stare stems from the fact that we know comparatively little about the third leg of the nation's economy. Largely thought of as humanitarian—they don't care to earn a profit, for goodness' sake—nonprofits nonetheless occupy a major portion of the economy. In Minnesota, nonprofits employed almost 10 percent of the workforce and reported almost $24 billion in revenues last year. Nationwide, the sector holds assets topping $3 trillion. A paper by the Aspen Institute in Washington, D.C., called the nonprofit sector "one of the least understood segments of national life, yet also one of the most crucial."

The reasons we don't know much about the nonprofit sector are both simple and complex: Simple, because we just don't collect much data on nonprofits. The majority of nonprofits are not even required to file tax returns. This also hints at the complexity. With private for-profit industry, we have a shed full of tools for measuring short- and long-term economic activity—prices, income and gross product statements, income tax returns, licensing and other registrations, bank lending records, and innumerable surveys by government and other entities on employment, capital spending, current orders, production utilization, future expectations—you get the picture.

Virtually none of these measures is available or reliable for the nonprofit sector. Employment might seem both useful and accessible for gauging nonprofit activity. But it is not widely or closely tracked, and available figures don't even attempt to include volunteer labor, an important element of nonprofit activities. Moreover, many traditional economic measures are not particularly relevant with nonprofits. For example, how might one measure the "output" of a homeless shelter or a veterans' association? How about gauging price trends for services that have always been free?

Despite data limitations, what we do know about nonprofits might surprise you: According to data from the Internal Revenue Service, the nonprofit sector has been growing rapidly over the past decade or two in terms of total organizations, revenue and assets. According to unique job-tracking efforts in Minnesota, nonprofit employment appears to be going gangbusters as well. The nonprofit meek, if you will, are inheriting a bigger share of the earth.

That growth, however, is not uniform in terms of geography or among the many different types of tax-exempt entities allowed by law. And though the sector's revenues have never been higher, it's trying to adapt to short- and long-term funding challenges.

Those present, say I

Trying to paint a neat summary of nonprofit trends in the Ninth District gets messy quickly. People generally lump all nonprofits together—as does a lot of research on this topic—when in reality, nonprofits represent an amalgamation of organizations, with widely varying missions, sizes and revenue streams. Much of the data available might be generously called "suggestive" (see sidebar on data issues).

But with those caveats, there are some clear, notable trends among nonprofits, both nationally and in the district. First, as a group, they are growing fast: The number of U.S. nonprofits registered with the IRS has jumped by 30 percent since 1996. Nonprofit growth over this period varies among district states, from a high of 37 percent in Montana to a mere 1.6 percent in North Dakota, according to data from the National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCCS), which operates a comprehensive database of nonprofits using IRS tax returns.

Hidden among such macro data is a host of other interesting trends. In layman's framing, the nonprofit sector can be thought of loosely as three groups: public charities, private foundations and noncharitable organizations (see sidebar below for brief taxonomy of nonprofits), each of which is growing at different rates in different states. Roughly summarized, charities and foundations-501(c)(3)s, in IRS-speak-are seeing strong growth nationwide and among district states, with the general exception of North Dakota (see chart).

Conversely, noncharitable organizations saw their numbers decline by 5 percent across the country. This group includes social associations, business and labor groups, and sundry other organizations that are tax exempt, but cannot offer tax deductibility for charitable donations. District states saw even greater decline within this group, with five states registering a drop of 13 percent or more.

In Minnesota, for example, fraternal beneficiary societies and other 501(c)(8)s saw their numbers cut in half from 1996 to 2006. Worse, their annual revenues fell more than 75 percent. Wisconsin had more than 3,000 such organizations in 1996; a decade later there were only 1,450.

According to Jon Pratt, executive director of the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits (MCN), "There's kind of a trend away from membership organizations. ... People aren't participating in Lions' and Moose clubs—the animal groups—as they used to."

That's not to say that overall participation is down among nonprofits. Rather, it's up, but distributed differently, said Pratt, because many people today are involved in charity nonprofits, which they also use as a social outlet. So rather than joining a membership nonprofit, such as Rotary, Pratt said, now people work with Habitat for Humanity, where they can contribute directly to a cause and get their social fix all at the same time.

As a result of these coincident patterns, the nonprofit sector has become much more concentrated in 501(c)(3)s over a relatively short period. In terms of market share over the past decade, Michigan, Minnesota and Montana saw the number of public charities and foundations rise from about 50 percent of the nonprofit sector to about 65 percent. The same general trend held in Wisconsin and the Dakotas as well.

Mostly small, yet bigger and richer

Most nonprofits are small. The IRS requires financial reporting from only those nonprofits with revenues over $25,000. That might seem like a low threshold, but only about 40 percent of nonprofits cross over it. The remaining 60 percent only have to register with the IRS.

Among this higher-revenue subset of nonprofits, the number of nonprofits that filed IRS Form 990 grew by 33 percent over the past decade—just a bit faster than nonprofits as a whole. Among district states, Montana had the largest increase in 990 filers, at 45 percent, while North Dakota again saw the slowest growth, 12 percent.

In fact, given the flat overall growth among all nonprofits in North Dakota, and its modest 12 percent growth among 990 filers, the number of very small nonprofits in the state actually declined over the past decade, which bucks a consistent growth trend among small nonprofits elsewhere in the district and across the country.

Population decline and struggling rural economies likely explain at least part of the stunted nonprofit activity in North Dakota, because those things affect funding from both individuals and businesses. Foundations are also relatively scarce in the state (see more on this topic in "The leader of the nonprofit pack").

As a result, the state has limited access to funding compared with many other states, such as Minnesota, said Gerald Skogley, a retired executive from the Bush Foundation and now a board member of the North Dakota Association of Nonprofit Organizations. Newer agencies have a harder row to hoe than older, more established organizations that have dependable support year after year from individual donors, churches, local businesses and other sources.

And though nonprofits are predominantly small, as a group they are getting bigger and richer—not all of them, certainly, but the overall trend is unmistakable. In the past decade, gross annual receipts have almost doubled to $2.4 trillion dollars. Total assets held by nonprofits doubled to $3 trillion. (And remember, receipts and assets are counted only from those organizations filing 990s, or about 40 percent of nonprofits. So those numbers are conservative.)

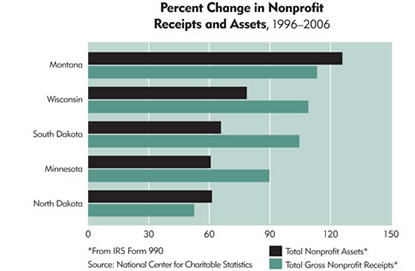

Montana outperformed the national average for both receipts and assets over this 10-year period, as well as remaining district states in this category. (See chart below; Michigan was not included because an apparent—and astounding—five-fold increase in receipts over the past decade to $270 billion could not be verified or traced to logical sources.)

Rather than everyone sharing the wealth, the explosion in revenue and expenditures tends to be concentrated in larger nonprofit organizations, particularly health care and education. In Wisconsin, these two nonprofit subsectors make up about one-fifth of larger nonprofits (those filing 990s), but lay claim to about three-fourths of the revenue. In Montana, 8 percent of larger nonprofits are in the health care field, as is 60 percent of revenue, according to NCCS data.

Take this job and love it

As you might expect, a ballooning number of organizations means more nonprofit workers. Today, nonprofit employment is estimated to be larger than the transportation, agriculture, finance and insurance sectors, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and nonprofits employ about as many workers as durable goods manufacturing, a sector that public policy officials, economists, financial markets and the general public tend to obsess over.

Like other economic data on the sector, nonprofit employment data are not particularly firm (see data sidebar). Minnesota offers a rare exception. The state Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED) can flag nonprofits in quarterly survey data because of their exemption from the state unemployment insurance program. It provides these data annually to MCN, according to Christina Macklin, a policy analyst with MCN.

Maybe other states should do the same, because business leaders and policymakers might find it interesting that employment in the Minnesota nonprofit sector has been going great guns. Based on MCN's figures (provided by DEED), nonprofit employment in Minnesota grew by 48 percent from 1993 to 2004 to more than 250,000 workers-an annual average growth rate of 4.4 percent. Employment grew every year during this period, even through the recession.

To put that performance in perspective, Minnesota's private sector employment grew 20 percent over this same period, which was better than the national private sector average by a shade. Nonprofit employment even beat its private sector counterpart from 1993 to 2000—a period of extraordinary employment expansion in the private sector. In 2004, employment in the nonprofit sector in Minnesota grew by 1 percent—not terribly bad by private sector standards, but the lowest annual rate of growth for nonprofits since the mid-1980s, according to MCN, and widely attributed to tight funding, particularly from government.

Much like revenue growth, most employment growth in Minnesota has come in the health care sector, which employs two-thirds of nonprofit workers, according to MCN. Some have surmised that the disproportionate share of nonprofit employment in health care is why the sector's total employment didn't dip during the recession. But most other subsectors have also shown strong growth over the past decade or so—evident in the fact that employment market shares among the handful of nonprofit categories tracked by MCN have changed little since 1993.

Less is not more

Given the numerical and revenue growth among nonprofits, you might think the industry mascot was the bluebird of happiness. But just plain blue might be more accurate. That's because overall funding is not as flush as the data might suggest. As the number of charitable nonprofits grows, the revenue pie—while also growing tremendously—is being disproportionately consumed by health care nonprofits, leaving the rest of the nonprofit field to fight over the crumbs.

There are only a few major funding sources for most nonprofits: charitable donations, direct government grants and program fees for services provided (a significant portion of which originates from government as well). Charitable giving as a whole has been strengthening of late, but many nonprofits saw giving sag during the recession (see "Charity case: Trends in giving" for additional discussion on giving).

That leaves government as a major source of revenue for most nonprofits, through either grants or program fees. In Minnesota, the smaller the organization, the more dependent it is on government grant funding (as well as individual donations), according to a 2005 report by MCN. Those with revenues under $1 million get 22 percent of their revenue (on average) from government grants; for those with revenues between $1 million and $10 million, the percentage declines to 17 percent, and just 3 percent for those with more than $10 million in revenue. The funding proportions flip when it comes to program fees: The largest nonprofits, which include the majority of health care and education nonprofits, derive 83 percent of their revenue from program fees. For the smallest nonprofits, program fees make up just 34 percent of revenue.

In the past, government at all levels provided a lot of its own services. That has slowly changed; today, many services are paid for by government, but delivered by nonprofit and for-profit organizations. "There is a consensus not to add more government employees, but continue to add more government services," said Pratt of MCN.

That spigot of government funding has likely fueled the organizational growth of nonprofits. According to a 2005 report by the Aspen Institute, nonprofits derived about $288 billion in revenue from the federal government in 2005—about two and half times 1980 levels after adjusting for inflation. The report calculated that better than 80 percent goes to health care nonprofits, thanks to programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Still, other nonprofits took in an estimated $50 billion from federal sources in 2005.

All that government spending has also created something of a dependency problem, because government funding is undergoing "retrenchment," according to Pratt: "There's this desire (to think) that if government pulls back, others will fill this (funding) space and provide the necessary services."

A number of sources said nonprofits have turned to foundations to help fill the void. Anita Pampusch, president of the Bush Foundation in St. Paul, said that foundations can only do so much for cash-strapped nonprofits, in part because of lagging investment returns for foundation endowments (which generate annual grant funding) early in the decade. The Bush Foundation endowment is still short of 2001 levels, she said.

According to Carleen Rhodes, president of the St. Paul Foundation, "Many did turn to the foundation community for support, but the capacity just isn't there to make up the gap." That shouldn't be surprising: According to Aspen's data, nonprofit revenue from just the federal government is roughly 10 times the amount of annual foundation giving.

"No matter how much charitable giving can increase, it is a drop in the bucket compared to governmental funding for primary issues," said Ruth Ascher, executive director of United Way of Southwest Minnesota, via e-mail. "When core, supportive programs are defunded by government, nonprofits are hard pressed to pick up the slack."

It's difficult to say how deep "retrenchment" will be, or what it means in actual dollars, but the Aspen Institute has taken a stab at it. A 2006 analysis of five-year federal budget plans, based on the president's 2007 budget submitted to Congress, found that direct funding to nonprofits would likely be cut by a cumulative $14.3 billion over five years. Nonprofits in community development, income assistance, and education and research would be the hardest hit, according to the report, while those in health care would have brighter funding prospects.

That's on top of existing funding woes, much of them caused by the national recession that pummeled first the economy, then local and state budgets, before slamming nonprofits. In 2003 and 2004, more than 40 percent of nonprofits reported deficits for their fiscal year, according to an MCN report last year. "Some nonprofit organizations in Minnesota are nearing financial crisis as their major sources of revenue—particularly government funding—have been on the decline in recent years," the study said. It found that nearly half of the nonprofits surveyed had experienced cuts in state and local funding—at the same time that two-thirds of respondents said demands for services were increasing.

Some evidence suggests that certain sectors are winning the funding battle. For example, Mark Wilson, an associate professor at Michigan State University who has tracked nonprofit trends in the state for years, has found wide fluctuations in average revenue among 26 categories of nonprofits. Nonprofits in arts, environment, health, ag/nutrition, public safety, and recreation and leisure all saw annual revenue growth of at least 4.8 percent from 2000 to 2003. Conversely, nonprofits with missions in community improvement, philanthropic/volunteer, religion/spiritual development and public/society benefit all suffered annual revenue decreases of 3.5 percent or more.

A more friendly cage match

Numerical growth among nonprofits has exacerbated the funding problem, pitting organizations against each other for limited funds, said Nancy Straw, president of the West Central Initiative, located in Fergus Falls, and also a member of the Minneapolis Fed's Advisory Council on Small Business and Labor. Corresponding by e-mail, Straw said the recession has left many organizations "reeling, even years later." But the real problem is that organizations have tended to shift their immediate focus, she said. Rather than focusing time and energy on their service mission, "some organizations are chasing funds to keep their doors open."

Not all organizations suffer to the same degree. Those nonprofits with strong board leadership, solid management and fiscal stability "weather up and down economic conditions fairly well," said Bob Sutton, head of the South Dakota Community Foundation, via e-mail. "Like the for-profit sector, those organizations that have not planned for ongoing funding or do not have contingency plans in place fare the worst."

When tough times hit private industry, businesses tighten their belts. If that's not enough, market forces will weed out the inefficient. Something similar—and something different—appears to be happening in the nonprofit sector. For example, sources widely report that they are seeing greater belt-tightening and improved organizational efficiency among nonprofits. In some cases, nonprofits are taking a page out of the business textbook, consolidating business operations and even merging with other nonprofits.

According to Trixie Golberg, president of the Southern Minnesota Initiative Foundation, the recession had "lasting impact" on how nonprofits do their work. More are looking at their organizational and financial infrastructures "with an emphasis on resiliency," she said by e-mail. "We have seen nonprofits collaborate and combine in new ways. Many nonprofits discontinued entire program areas." She also noted that more nonprofits have started endowment and planned giving programs in an effort to "be more innovative" in their financial planning.

Carleen Rhodes, from the St. Paul Foundation, said she sees evidence of nonprofits getting smarter all the time. The foundation is even leading by example, recently combining back-office operations with the Minnesota Community Foundation and two other private foundations. This arrangement allows them to share staff, which lessens the resources devoted to basic operational matters like accounting, and expands the foundation in mission-specific areas.

Rhodes is also seeing nonprofits view each other more as potential collaborators and less as competitors, in part because of a growing awareness that fundamental problems or causes that nonprofits are organized to address—early childhood development, domestic abuse, environmental cleanup—are really a series of interconnected problems or forces. By extension, Rhodes said the role of foundations "is to help organizations find their way to other complementary partners."

It's hard to say whether any of these changes will put the industry on a better footing. Nonprofits appear to bend over backward to maintain staffing levels, resorting to alternative cost-saving measures—reducing hours or freezing or reducing wages and benefits—before taking the drastic step of laying off workers. While that might be in sync with nonprofits' humanitarian mission, it might not be a good organizational strategy.

And despite the talk of mergers and consolidation, there appears to be no slowdown in the total number of nonprofits. Few sources could identify more than one or two nonprofits that actually closed their doors. One North Dakota source said he believed that "too many (nonprofits), once established, stayed in business to perpetuate themselves and staff for economic reasons" when times got tough or when their task was completed or assumed by government or some other agency.

We hardly know ye

A lot of other nagging issues crowd the nonprofit agenda. Although surveys show nonprofit workers find great satisfaction from their work, turnover is problematic in part because of lower-than-average wages. College graduates are leaving school with higher average debts, making nonprofit jobs a tough sell on campus.

Congress has also been shining a spotlight on high executive compensation and abuse of nonprofit status. Within the district, the Minnesota Legislature has considered proposals to cap nonprofit salaries. Most in the industry said they believed these problems are overblown. Pratt noted that the industry's wages are 13 percent lower on average than those in the private sector.

Other issues are more fundamental, like erosion of financial support and a problem-of-the-month mentality among the public. As one South Dakota source noted, "Unfortunately, the social ills change right in the middle of the game. If fetal alcohol syndrome and teen pregnancy are the social problems of today, and methamphetamine rears its head, the priorities change immediately. This is a constant issue."

Underlying many of these issues is a superficial understanding of the role nonprofits play in the economy. A 2004 study on the state's nonprofit sector by the Michigan Nonprofit Research Program noted that nonprofits "are often commended for their contribution as a 'safety net' providing valuable services to a state's residents, but rarely are these organizations cited for the contributions they make to a state's overall economic vitality and success."

Pratt said the mainstream media mostly gloss over the nonprofit industry, profiling individual organizations and favoring emotional stories over economic ones.

But the media are hardly alone in their view of the sector. "It's not seen as part of the economy," Pratt said. "It's seen as a dependent part of the economy, rather than as a contributor."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.