Car donated to Boys' Ranch, and $50 to church this month. Then there was the bag of clothes for Easter Seals. Volunteered for the cancer fun run.

Now get out the calculator: What's it all add up to?

Some charitable giving is relatively easy to track, and recent data show that monetary generosity is increasing. But like other data on the nonprofit industry, many measures on giving are not particularly straightforward. Then there are in-kind contributions like volunteering that are no less valuable than cash donations, but are harder to measure in economic terms.

In 2004, charitable giving in this country hit almost $250 billion, according to the most recent report by the Giving USA Foundation, a research arm of the American Association of Fundraising Counsel. That's a 5 percent increase over the preceding year, prompting the group to claim that charitable giving had gotten "over the hump" of stagnant donations caused by the national recession earlier this decade. In Minnesota, for example, individual and foundation giving remained virtually unchanged from 2000 to 2003, according to the Minnesota Council on Foundations.

Kathy Gaalswyk, president of the Initiative Foundation in Little Falls, Minn., said via e-mail that the economic downturn earlier this decade reduced giving by businesses across the board, mostly because when firms struggle to turn a profit, many find cutting charitable donations "an easy and early budgetary adjustment to make."

The effect of those cuts isn't spread evenly among nonprofits. According to Giving USA, in recent years, nonprofits that received more than $1 million in contributions were more likely to report increases in charitable giving, while those with less than $1 million in contributions were less likely to see increases. The organization attributed the poorer prospects of small nonprofits to a lack of fundraising staff—a vital asset, particularly in lean years when there is more competition for diminished funds.

But even during the recession, Americans continued to be comparatively generous. Beginning in 1999, charitable giving exceeded the threshold of 2 percent of gross domestic product for the first time since 1971 and has stayed above that level ever since. Other measures also show a long-term increase in giving. According to testimony last year before the House Ways and Means Committee, total charitable tax deductions (in constant dollars) increased from $43.7 billion in 1975 to $145 billion in 2002.

Some fret over "donor fatigue," given the slew of catastrophic events—the Gulf Coast hurricanes, the Pakistan earthquake, the 2004 tsunami, 9-11—that have hit the United States and elsewhere in the past half-decade, generating major charitable outpourings. The fear was that such donations would merely displace day-to-day donations that people make to their favorite charities; after all, the Gulf Coast hurricanes have generated $3.4 billion in charitable contributions, according to the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University.

A survey of nonprofits by the center found that about one-third believed that hurricane-related donations had an immediate and negative—but ultimately short-lived—effect on their organization. A giving outlook report by the Minnesota Council on Foundations found that 61 percent of grant-makers gave disaster donations over and above their budgeted levels. However, 18 percent said they did cut back on their usual grant-making to carve out some disaster relief help.

But other research shows that most individual donors—though not all—simply reached a little deeper into their pockets. According to a survey earlier this year by the Conference Board, a nonprofit market research organization, nine of 10 individual donors continued to give money to the charities they traditionally supported.

Saint or scrooge?

Still, charitable generosity is in the eye of the beholder, dependent on circumstances, need, available resources and, of course, whatever data put the beholder in the best light.

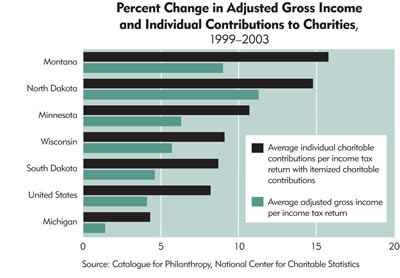

According to Internal Revenue Service tax data, individual contributions from 1999 to 2003 also grew faster than adjusted gross income in every district state, and for the nation as a whole. For example, in Montana, gross income grew by 9 percent over this period, but average charitable giving increased by almost 16 percent (see chart).

But philanthropic tendencies diverge in some states when weighted as a percentage of income. According to IRS tax return data on itemized charitable contributions (crunched by the Catalogue for Philanthropy and the National Center for Charitable Statistics), South Dakotans have hearts of gold, giving almost 12 percent of their adjusted average income in 2003. On the other end of the generosity spectrum in the district, Wisconsin's average giving was less than 6 percent of average adjusted income. Just such a relationship is evident in the widely cited Generosity Index by the Catalogue for Philanthropy, which trumpets the fact that low-income states tend to rank high in generosity when their giving is measured as a percentage of income.

Like virtually all economic measures of the nonprofit sector, however, data on giving come with a lot of footnotes. For example, the generosity of South Dakotans might be methodologically inflated. Here's how: Adjusted income for a state is averaged from all tax returns, while charitable contributions come only from itemized tax returns—a small subset of all returns, which likely includes proportionately more higher-income returns.

That's not all. In South Dakota, the number of charitable itemizers is particularly small—about 13 percent of all tax returns—while supposedly less generous states such as Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin have charitable itemization rates above 31 percent.

As a result, there could be some selection bias involved here: Those with higher incomes tend to itemize deductions. As the percentage of itemizers shrinks, this group's average income—and charitable giving—likely rises compared with non-itemizers. In fact, raw figures on total charitable giving suggest that states with low rates of tax itemization (like the Dakotas) might be the real charitable scrooges. For example, in 1999, the percentage of total itemized charitable deductions was just 1.4 percent of adjusted income from all returns for both North and South Dakota, while it was above 2 percent for Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

One final who's-on-first: Even this measure has gaps, because it doesn't include charitable contributions—and certainly there are some—from non-itemizers. This would change overall giving figures considerably, given that non-itemizers exceed 80 percent of taxpayers in the Dakotas.

Helping hands

Any analysis of charitable giving trends also needs to look beyond the balance sheet, because nonprofits leverage significant resources through the use of volunteers.

Mark Hiemenz, from Hands On Twin Cities, an organization that helps match volunteers with nonprofit organizations, said via e-mail that volunteers "are more important than ever for nonprofit organizations," particularly at a time when budgets are tight and organizations "are looking to do more with less."

A look at volunteerism trends—the proportion of people who volunteer, and the amount of time they spend doing it—quickly exposes some data gremlins. For example, a periodic survey by researchers at the University of Minnesota shows that two-thirds of adult Minnesotans volunteer, a level that has crept up slightly over the last decade. On average, they donate close to 190 hours a year.

However, surveys by the Bureau of Labor Statistics put national rates for volunteerism below 30 percent for those 16 and older, and annual volunteer hours at about 50. Though Minnesota is known to be progressive, the disparity is more likely to be rooted in methodological differences in the surveys. For starters, the Minnesota survey included volunteer activities for school and other government entities, as well as informal opportunities like coaching.

Measuring volunteerism at the organizational end might get closer to the mark. According to survey research by the Management Capacity study, a cooperative project between government and a number of nonprofits including the Urban Institute, 80 percent of nonprofits use volunteers. Coordinating a volunteer labor force is much trickier than it might seem-at least in terms of exacting good outcomes for both the organization and the volunteer. It's a human resource challenge from a variety of angles.

For example, changing lifestyles and demographics (more single-parent families and dual-income households) are having an impact on volunteerism. When most adults work, getting day-time volunteers can be particularly challenging. Numerous sources indicated that nonprofits tend to prefer long-term volunteers, but many individuals and groups are looking for one-time or short-term opportunities. For some volunteers, the social connections gained through volunteering might be as important as the cause itself.

Tony Nathe, volunteer coordinator at Talahi Senior Campus, an elderly housing and health care organization in St. Cloud, Minn., said short-term volunteers, particularly students, are fairly easy to find, but they require more attention and training. Regular volunteers who want to "do good for fellow mankind" are harder to find, Nathe said.

Nancy Anderson is the volunteer coordinator for the City of Plymouth, Minn. She said via e-mail that more people are interested in volunteering than in the past, but they also have less time—so they tend to avoid long-term assignments. "I have a lot of volunteers who come out to help at special events," Anderson said. "They get the feeling of helping out, they feel part of their community, but they only have to put in three to four hours."

A rising number of nonprofits means there is a wider variety of volunteer opportunities available. People move more frequently, meaning they might not sustain close ties with neighborhood organizations. Volunteers also "want to sample many different kinds of volunteer positions," Anderson said. "People are more concerned about getting a good fit rather than just helping out. I think the days of a woman signing up to be a pink lady at a hospital and staying in that position for 25 years—I know a woman from church who has done that—are over."

Portals into volunteering appear to be changing as well. Hiemenz said that corporate volunteerism "has become a much larger way for individuals to become engaged over the last 15 years." He said research shows that corporate volunteerism is good not only for the community, but also for the company and its employees.

Sources also said that families see volunteering as a way to get an easy two-for-one: With busy family schedules, volunteering offers some family time together, and it's for a good cause. Hiemenz said working families can even get a three-for-one deal, as corporate volunteering increasingly allows for family participation.

The solution is not to bemoan such changes, many sources said. Rather, shifts in volunteer lifestyle and motivation call for nonprofits to better understand and manage their volunteers, and match opportunities with people's interests. But that appears to be easier said than done.

Volunteers "want to be engaged. They don't just want to stuff envelopes. ... (But) there's a direct lag in organizations' ability to use those volunteers effectively," said Judie Russell, retired director of volunteer services for the Children's Home Society and Family Services in St. Paul. Russell, who was recently appointed to ServeMinnesota, the state's commission for national and community service, noted that high-schoolers are volunteering more, and she expected baby boomers to do the same as they reached retirement. She acknowledged the trend of "cyclical volunteers—they pop in and out," but added, "There is a segment willing to make the investment" in making a difference in society.

Coordinating more volunteers—and more engaged volunteers—requires more skill from organizations, said Russell. Are nonprofits responding to the challenge? A small number have, she said, "but not nearly the increase necessary. ... There is not the level of sophistication necessary. That's clearly the issue."

The problem is fairly basic: Many nonprofits don't have dedicated staff to coordinate volunteers. Those that do often have little formal training, or they dedicate only a fraction of their time to this particular duty, according to the Volunteer Management study. Russell and others pointed to various efforts at the state and national levels to help nonprofits take advantage of valuable, free human resources.

Nonprofits devote a lot of time and attention to applying for grants and pursuing other charitable giving in an effort to compete for limited funding. Russell said nonprofits have to adopt the same mentality when utilizing their equally precious volunteer resources—or else.

"Someone has to organize it, and do it well, or that will drop too."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.