Today's national banking system could be described as one that was largely molded by strict regulation and is now being remolded as that regulatory straitjacket is incrementally and steadily loosened.

Previously, strict laws dictated both banking activities and the geographic areas in which banks could operate. The underlying motivation for this regulatory environment—originating in the 1930s in reaction to bank failures that precipitated the Great Depression—was to provide banks with a narrowly defined business model and then protect them from excessive competition under the notion that it would lead to a more solvent and safe banking industry. And in fact, it accomplished just that: Between about 1934 and 1984, bank failure rates were exceedingly low, and new entrants were few.

What evolved over this period was the creation of separate banking systems in each state. Regulations on interstate banking prevented expansion by and competition among banks in different states, and intrastate regulations kept an artificial lid on branching within most (but not all) states.

Subsequent banking deregulation has been widespread, but its adoption and absorption has been gradual among individual states. In many cases, deregulation of interstate and intrastate banking has come more slowly to district states than elsewhere. (Here and elsewhere, "interstate and intrastate banking" refers to bank chartering and ownership as well as branching.)

One less brick in the wall

Banking deregulation has both a long and recent history, dealing mostly with geographic expansion and growth of bank powers (allowable products, really).

The last major bank legislation, for example, was in 1999 when federal law (known as Gramm-Leach-Bliley for its congressional authors) tore down the walls between banking, securities and insurance, allowing each industry to dabble in the products of the other, something that had been outlawed since the early 1930s.

These efforts got a boost from a third leg—the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980—that gave banks more freedom on deposit interest rates.

Up to that point, "banking was fairly cookie-cutter," with the Federal Reserve Board setting maximum rates on bank deposits, according to Stan Koppinger, president and CEO of Merchants Bank, a $45 million bank in Rugby, N.D., via e-mail. "I can remember looking at the card supplied to us from the Fed which told us how much we could pay for certificates of deposit out to seven years. All banks in the United States paid the same."

After the new law was passed, "banks were allowed to compete [for deposits] more freely with each other," according to Koppinger. "In my mind, this was the change that ignited the current mentality that all bets are off. ... We [could] no longer rely on old systems and business as usual."

Later deregulatory efforts complemented this by giving banks greater ability to expand geographically and to compete in new markets, and giving them something to compete for. But liberalization in the geographic expansion of banks sometimes took years, even decades to fully take hold, often because states (which also regulate banks) weren't as aggressive in peeling back regulation.

For example, the federal Douglas Amendment to the 1956 Bank Holding Company Act permitted a bank or bank holding company to purchase a bank in another state only if the second state's government permitted such acquisitions (though there were grandfathered exceptions to this rule). Nothing much happened at first because most states prohibited acquisitions by out-of-state banks. Maine was the first state to allow such transactions, doing so in 1978, followed by Alaska, Massachusetts and New York in 1982. Shortly thereafter most states entered into similar regional or national reciprocity arrangements, and this deregulatory effort finally got on its feet.

South Dakota was the first district state to allow interstate bank purchases in 1983—and was a district leader in most deregulatory aspects—while other district states were generally slow in joining the party. By 1990, all but four states permitted at least some type of cross-border purchases, but two that didn't were Montana and North Dakota.

Then in 1994, the Riegle-Neal Act completed the Douglas Amendment phase of deregulation by mandating that states allow interstate bank purchases by 1995. Montana was among the last holdouts; it did not permit acquisitions of its banks by out-of-state firms until 1993.

Branching is another major deregulatory area that federal and most state regulators have eased into. Prior to 1975, 12 states explicitly prohibited any type of branching and another 34 states had restrictions of varying severity; only four states allowed liberal branching (one of them being South Dakota).

Intrastate branching—or branching by banks in their home state—was the first sector to be liberalized. By 1992, all but four states allowed some type of statewide branching. Again, save for South Dakota (which had fewer branching restrictions by 1970), district states were comparatively late in deregulating intrastate branching. Michigan and Wisconsin granted their banks this power in 1988 and 1989, respectively. North Dakota and Minnesota didn't allow limited branching until 1988, with Montana following their lead in 1990. But as late as 1996, Minnesota, Montana and North Dakota were three of only 12 states that still had some controls on statewide branching.

Riegle-Neal also permitted interstate branching—where a bank holding company can extend branch offices into out-of-state markets where a subsidiary holds a charter (aka head office). States were allowed to opt out of this provision, though Texas and Montana were the only states that did. Montana was the last state in the nation to finally allow interstate branching in 2001.

Finally, Riegle-Neal open the door to de novo branching for the first time as well. This measure allows a bank to branch in another state without having an established charter in that state. Because states must pass legislation expressly permitting such activity within their borders, adoption of this measure has been very deliberate. To date, Michigan and North Dakota are the only district states that allow de novo branching, and both are on a reciprocal basis with the other 16 states that allow the activity.

Presence of out-of-state banking firms still small

The net effect of deregulation to date has been both profound and stunted. Branching has skyrocketed (see "In banking, less can equal more"), while expansion of interstate banking has been much more subdued.

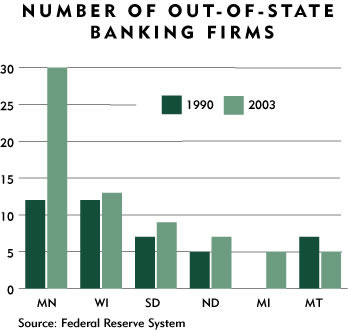

North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin have seen a net gain of only a couple of nonnative banking firms since 1990, and Montana has actually registered a decline over this period. Minnesota gained 18 firms (net) during this period, but out-of-state banks still comprise a relatively low percent of the total number of unique firms operating there. In percentage terms, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan has seen the greatest increase in out-of-state firms, but that's in part because it had none in 1990.

There are several likely reasons why cross-border banking is still a nascent trend. First, deregulation is relatively fresh in historical terms, particularly in some states. With the chains of intrastate branching unbound, banks may be busy enough expanding in states where they already have a presence, rather than in those they don't. Among

in-state banks, branching growth has been particularly strong in larger markets—arguably the most attractive market for an out-of-state bank to enter.

It probably also has something to do with the rural and small-town markets that dominate most of the district. "To a [big] banking firm, we're a very rural state," said Rosalie Sheehy Cates, executive director of the Montana Community Development Corp., a nonprofit agency that often partners with banks to make loans to small businesses.

With "lots of one-town banks" in the state, Sheehy Cates said, "we don't have a very corporate face to our banks here. ... To be a bank in Montana, you have to know how to serve the local community."

Laws that giveth and taketh awayOver the past century, countless laws have helped shape and reshape the structure of the banking industry today. Below are a few of the major deregulatory laws of the last 50 years. Bank Holding Company Act of 1956: Required Federal Reserve Board approval for the establishment of a bank holding company, and prohibited bank holding companies headquartered in one state from acquiring a bank in another state. Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980: Began the phaseout of interest rate ceilings on deposits, established a formal Depository Institutions Deregulation Committee, granted new powers to thrift institutions and raised the deposit insurance ceiling to $100,000. Depository Institutions Act of 1982: Expanded FDIC powers to assist troubled banks, and expanded the powers of thrift institutions. Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994: Relaxed capital requirements and other regulations to encourage the private sector secondary market for small business loans. Contained more than 50 provisions to reduce bank regulatory burden and paperwork requirements. Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994: Permitted bank holding companies to acquire banks in any state one year after enactment. Beginning June 1, 1997, allowed interstate bank mergers. Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork Reduction Act of 1996: Modified financial institution regulations, including regulations impeding the flow of credit from lending institutions to businesses and consumers. Amended the Truth in Lending Act and earlier housing law to streamline the mortgage lending process. Amended or eliminated various application, notice and recordkeeping requirements to reduce regulatory burden and the cost of credit. Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999: Repealed remaining vestiges of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 that kept banking, securities and insurance functionally separate as businesses. Also granted some regulatory relief to small institutions by reducing the frequency of their CRA examinations if they have received outstanding or satisfactory ratings. (See special issue of The Region, March 2000, dedicated to financial modernization.) Adapted from the FDIC's "Important Banking Legislation," which was developed from the 2004 report, "Major Statutes Affecting Financial Institutions and Markets," by the Congressional Research Service. |

|

Related articles: |

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.