(This is the final piece in a series investigating structural changes in banking in the Ninth District. See the November issue of the fedgazette for other articles.)

Banks have a special place in small-town America. Often they are among the oldest businesses in farm towns and other small cities dotting the rural landscape. Indeed, if it has a bank, then it's a town. Few other businesses have such widespread presence and influence, particularly in the faraway spots of rural America. The buildings themselves are testimonials to their local importance—still standing even if they are no longer home to a bank, but maybe a law or insurance office or even an antique shop.

But trends in banking over the last two decades have many fearful for the future of small community banks. Relentless consolidation has put small banks under siege, the argument goes, not only in rural areas but also in big cities, pressured by ever-expanding megabanks whose bottom line is their bottom line. Get big or get out.

There's a little myth and a little reality to the wistful longing for days gone by in community banking. In the past, strict state and federal regulations on bank startups, acquisitions and branching gave many small banks a certain amount of market turf and protection from competitors. Subsequent deregulation and other coinciding forces (like ATMs and other new service technologies) have exposed community banks across the district to steep competition. The result has been a steady decline in the number of community banks and considerable hand-wringing among those remaining.

But the same regulations that opened up markets to new competition are affording community banks new opportunities to remain competitive. And while deregulation has swallowed many community banks, it has also unleashed a fairly strong counterpunch from community banks that grabbed hold of new opportunities to merge and add branches. As large banks gobbled up a bellyful of other banks, there has been something of a renaissance in startup banks—almost by definition a small bank—that see an opportunity to beat the big, sprawling banks in customer service that starts with a name, not an account number.

As community banks compete for customers, most tend to keep their eyes not on their big-bank brothers, but on proverbial neighbors across the street—firms that are not banks, but act like blood relatives because they can offer many banklike services yet don't face the same type of regulation as banks.

Which way to what bank?

The trend in bank consolidation started rolling downhill about the mid-1980s and has been fueled by periodic bank deregulation at federal and state levels which, among other things, tore down artificial barriers to geographic expansion.

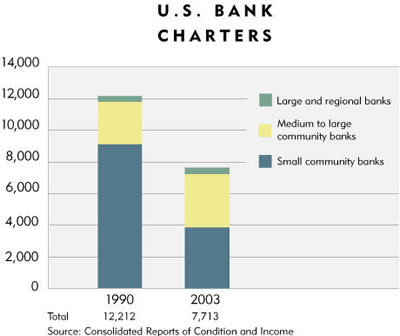

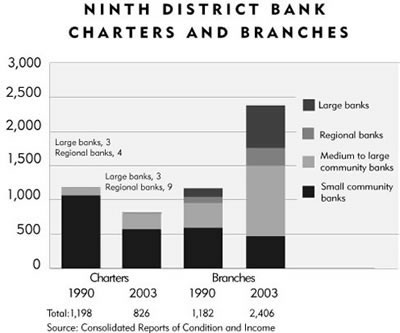

Most affected by this movement—in terms of firms—have been small community banks (typically those defined as having less than $100 million in assets). Since 1990, the number of banks with less than $100 million in assets has dropped by close to 60 percent, while the district saw a 46 percent decline (see chart below).

The reasons for the decline among small independent banks are many, but most can be traced back to the simple fact that deregulation opened local markets to greater outside competition, forcing community banks to go wingtip to wingtip with other (often larger) banks. Despite a public perception to the contrary, it's been a fight that community banks haven't really lost—since the early 1990s, bank failure rates have been exceedingly low.

Rather, small banks have dropped in number mostly because these firms have been attractive buyout targets. Deregulation made both bank mergers and branching easier, which increased local competition. This, in turn, created urgency for banks to find both new clients and operational economies of scale to reduce costs. Banks of all sizes found a ready solution in the thousands of small banks scattered throughout the district, whose owners likely saw a buyout as the best strategy for their bank in a deregulated environment. It might have meant the loss of a few jobs as certain functions moved to a new head office, but most of those small banks "lost" to consolidation are still open for business.

I'm feeling much better

Indeed, the health of community banks is good, and by some measures and anecdotes, very good. A 2004 Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) report on the future of banking found that community banks "maintained their presence in all types of markets—urban, suburban and rural," as well as in markets seeing both population growth and decline.

The report pointed out that a good portion of the decline among the smallest class of banks had to do with the fact that many simply outgrew the category during a period of heavy acquisitions and strong asset growth—evident in the increased number of banks with between $100 million and $1 billion. Also, their market share has more than doubled nationally (and tripled in the district) since 1990.

And whereas some trends—consolidation, asset concentration—are lamented as the death knell for community banks, plenty of evidence and anecdotes suggest that community banks have benefited from these very trends. A 2003 paper analyzing consolidation's effect on small business lending and community banks by researchers at the Fed's Board of Governors and the FDIC stated that "consolidation presented an opportunity for community banks."

Small business lending tended to slow among big banks involved in mergers during the period studied (1994 to 2000), while small business lending by community banks-often considered their bread and butter-rose, particularly in markets undergoing consolidation, according to the paper. "We find pretty consistent evidence that the 1994-2000 period in general and consolidation in particular were good for community banks."

Deregulation was fretted as a pox on community banks because it made it easier for competition to come to town, often in the form of branches. While large banks have aggressively pursued branching, community banks have also looked to branching as a way to stay competitive, particularly for those banks with more than $100 million in assets. From 1990 to 2003, the number of branch offices in the district doubled, with a total of 1,700 new branches opened (along with almost 500 closures). Almost 800 (46 percent) new branches belonged to banks with fewer than 10 branches, according to an analysis by the fedgazette (see chart).

In Montana, for example, the vast majority of banks are small (median size is $63 million), yet the number of banks with branches has grown by 50 percent since 1990 and the total number of branches exploded sevenfold to 275 as of last year. In many cases, community banks are expanding in nearby small towns—markets they know and understand.

"I don't have any hard numbers, but most of our smaller banks that have branched went into neighboring communities without any banking services," said Bob Fitzsimmons, deputy commissioner in the Montana Division of Banking, via e-mail.

The same was true in North Dakota. Don Forsberg, executive vice president of the Independent Community Banks of North Dakota, said there was a notable move among community banks into other small, unbanked communities to diversify loan portfolios and look for new customers to offset sagging loan volumes in declining rural areas.

One intriguing, and probably still nascent, trend is the expansion of rural community banks into larger markets—the little fish swimming into the big pond. Forsberg said that most new branches built in North Dakota in the last few years were by banks in smaller communities expanding in the likes of Fargo, Bismarck, Grand Forks and Minot. Fitzsimmons said such activity "has occurred in Montana but only in a few instances," usually among rural banks close to Montana's larger cities like Billings, Missoula and Bozeman.

The practice is fairly pronounced in South Dakota. A check of state records found that five of the last six proposals for new bank branches through June 2004 involved banks headquartered in smaller towns looking to branch into bigger cities like Watertown, Rapid City and Sioux Falls. (The other proposal involved a Sioux Falls bank wanting an additional branch there.)

It's alive

Still more evidence of a strong community bank sector is the relative vigor of startup, or de novo, banks. Nationwide, de novo activity all but dried up in less than a decade's time, going from a peak of 415 in 1984 to just 40 in 1992. But it has since bounced back, at least somewhat, with about 1,250 de novos nationwide since 1992, according to the FDIC. But given the overall trend in consolidation and declining bank numbers, a recent paper by the FDIC called the de novo growth "remarkable."

The district saw a total of 94 de novos sprout up from 1990 to 2003. Minnesota had the lion's share of startup banks, with 59—not surprising given the state's share of district population. But on a per capita basis among district states, Montana saw the strongest growth in de novo banks during this period.

Conventional wisdom on the matter suggests that consolidation is a major driver of de novo activity. Research tends to confirm this view. A 2003 paper by Steven Seelig of the International Monetary Fund and Tim Critchfield of the FDIC "shows a positive relationship between merger activity among market participants and de novo entry." In a 2000 report, William Keeton of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City found that the last half of the 1990s "provide[s] strong support for the view that mergers encourage the formation of new banks. Specifically ... markets with more merger activity experience higher rates of new bank formation, and that the mergers with the strongest link to new bank formation were those in which small banks were taken over by large banks or distant banks."

Bank executives of de novos—many of whom get "acquired" in a merger along with the building—often end up leaving the larger (acquiring) bank, returning to their community banking roots with the belief that profits await by serving smaller niche markets that get ignored by big banks.

Yes, but

That's not to say that community banks are finding themselves on easy street. Contact with more than two dozen bankers across the district indicates that increased competition is a way of life for all banks, large and small. But banks of different sizes might not always have the same competitors or face the same difficulties. For one, many small banks don't fear other banks, even the big ones.

"I would really welcome the challenge of another one of the bigger banks in my market," said Greg Traxler, president of First National Bank in Le Center, Minn., via e-mail. Located about 50 miles south of the Twin Cities, Le Center is a place the big banks have "never bothered" to expand into, Traxler said. "They are too big and can be too inflexible for a lot of small-town people."

But mention nonbank competitors and you'll get an instant rise out of most community bankers because these firms are getting their fingers deeper into people's wallet—what one banker called a "splintering of financial services markets to nonregulated entities" like mortgage and finance companies. It sounds odd to say, but banks used to dominate bank products—those products that people typically associate with banks. No longer.

A 2001 paper for the Federal Reserve Board of Governors looked, in part, at the competition banks faced from nonbank financial firms. Using data collected by the Federal Reserve's Survey of Consumer Finances, the authors found that the share of households using a commercial bank grew modestly from 1989 to 1998, thanks in part to a decline in the number of thrifts and, to a lesser degree, credit unions.

However, the share of households using a nondepository firm (like a mortgage company or auto leaser) for at least one service "increased substantially," roughly doubling to two-thirds during the same period. Depository institutions—commercial banks mostly, but also thrifts and credit unions—still had a tight hold on checking and savings accounts and certificates of deposit. But nonbank firms made serious headway into products like money market accounts, IRA/Keogh accounts and personal loans. In 1989, nonbank firms had just 15 percent of the personal loan market for things like mortgages and cars. By just 1998, their share had leapt to 42 percent.

Competition from nonbanks has likely increased on several fronts in district states, but it's hard to gauge exactly because as nonregulated businesses, very little information is collected from them, unlike from banks. For example, the onset of low interest rates in 2001 set off a frenzy of new mortgage companies in most states. The Minnesota Department of Commerce only started licensing residential mortgage originators in 1999, when it registered 1,284. Five years later, the number had more than doubled to 2,711.

As of June 2004, North Dakota had issued 351 mortgage licenses, only a "very small handful" of which went to banks, according to Sheryl Sailor of the state Department of Financial Institutions, via e-mail. But that doesn't mean there's a nonbank mortgage firm on every proverbial corner. Sailor noted that North Dakota does not require a firm to have a physical location within the state as a condition of licensing, and to date, only 57 licensees do. As a result, Sailor wrote, "I don't believe a vast number of them are conducting a great amount of business" in the state. Rather, entities are securing licenses "in the event there may be a possibility of conducting business here in the future."

Still, as many bankers pointed out, the breadth of competitors is growing, and even some seemingly innocuous organizations pose a threat. Farm Credit Services, for example, drew numerous complaints from district bankers, thanks to its entry into the rural mortgage market.

Paul Pieschel is president of Farmers & Merchants State Bank of Springfield, Minn., a town of about 2,200 in the agricultural southwestern part of the state. Pieschel noted that competition for his bank is coming from grain cooperatives. Many small grain co-ops have merged in recent years, and the newer, larger co-ops are opening finance offices. "They can give away the [higher] interest [rate] and capture all the farmers' business with higher margins in the sale of inputs," like seed and fertilizer, Pieschel said in an e-mail.

But nothing triggers the competitive ire of bankers quite like credit unions. The reason boils down to the fact that as a not-for-profit provider of financial services, credit unions get to act like banks without having to pay the corporate taxes of a privately held,

for-profit commercial bank.

Say what you will about the effects of deregulation and the spark-plug effect it has had on consolidation and increased competition among banks. According to Traxler, from First National Bank in Le Center, "[Deregulation] will not have the impact on me, here, that the credit union industry has," simply because of the tax advantage enjoyed by credit unions.

Nationwide, there are about 9,500 credit union firms—about one-quarter more than commercial banks. But their $610 billion in assets is less than one-third the $2 trillion held by commercial banks, largely because of limited branching. They are allowed to branch, but restrictions in expanding their so-called common bond (or field of eligible membership) has meant that credit union branching is much more limited than bank branching. Nationwide, credit unions have only about 9,500 branches, according to the June 2004 Consolidated Balance Sheet report issued by the National Credit Union Administration. Commercial banks, on the other hand, have about 68,000 branches nationwide.

However, credit unions continue to expand in other ways. Since the 1980s, common bond rules have been relaxed, offering credit unions the opportunity to gain members. And many are attempting to take advantage. This past June, the Soo Line Credit Union in Minneapolis and the Duluth (Minn.) Teachers Credit Union applied to expand their field of membership. Credit union membership has gone from 1 percent of the adult population in 1935 to 38 percent by 2001, according to a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. "Overall, it appears that credit unions, banks, and thrifts are more direct competitors today than when credit unions first appeared."

But bank sources also acknowledged that consumers are unlikely to complain about a hyper-competitive bank environment because tough competition "is generally always good for the consumer," said Eric Hardmeyer, president of the Bank of North Dakota, via e-mail. "There are more products and delivery channels for [banklike] products than there have ever been. Competition generally means providers have to sharpen their pencils and skinny up their prices," which pushes up deposit interest rates and keeps a lid on fees.

Playing favorites

At the heart of bankers' complaints is a deep-rooted belief that there are two sets of rules that create an oft-mentioned "unlevel playing field": a strict one for banks and a kid-glove, laissez faire one for nonbanks.

Julie Williams, chief counsel to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which regulates nationally chartered banks, testified to a Senate panel last June that "unnecessary [regulation] can become an issue of competitive viability, particularly for our nation's community banks, where bankers face competitors that offer comparable products and services but are not subject to comparable regulatory requirements."

The actual cost of regulation on an individual bank is hard to pin down. A 1998 Federal Reserve Board staff paper on the topic said regulation was "a small but not inconsiderable share of banks' costs." The author, Greg Elliehausen, noted that available evidence (going back to 1991) "is not very precise," but suggested that the total cost of regulation might reach about 12 percent of banks' noninterest expenses—half of which accrued in "activities that are undertaken only because they are required," most notably truth in lending requirements.

An increasing web of bank regulations also falls hardest on small banks. Regulations have scale economies in terms of compliance costs; in other words, the bigger the bank, the less it costs in percentage terms. This factor alone is enough to stimulate bank consolidation and discourage new firms from entering the market, according to Elliehausen.

Said a banker in Wells, Minn., "At some point, more and more of the little people in the small markets are going to say, 'It's not worth the hassle,' and sell to a neighbor or someone else who is willing to put up with all the regulations and oversight."

Struggling all the way to the bank

FDIC Vice Chairman John Reich told a Senate banking committee in June 2004 that the regulatory burden was "particularly important for community banks. ... Unless Congress takes action soon, community banks may indeed become an endangered species."

That's probably overly dramatic. For starters, many complaints from bankers today are not exactly new. "They are really long-standing complaints," said Chris Olson, deputy commissioner of the Montana Division of Banking. And as for credit unions, he said, "that's the fight that may never end."

Branching and de novo trends also run counter to the notion that small banks can't compete—to say nothing of recent strong profits throughout the industry, including its smallest firms.

One banker, president of a $220 million bank in north-central South Dakota, said it can be difficult for small banks to attract deposits—the capital seeds necessary to grow revenue-generating loans—particularly in slow-growing rural areas. "There's so much competition out there. ... If I'm out there in a $20 million or $30 million bank, I think it would be difficult to be competitive."

But he conceded that some bankers' complaints fly in the face of their own success—his own bank has averaged 10 percent annual growth in recent years. "It's the truth. We've had some good earning years. ... We are able to compete."

Jason Schmidt, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis senior quantitative analyst, contributed research to this article.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.