A command of mathematics is useful in farming, a calling in which making a living requires constant analysis of cash flows and rapid responses to ever-shifting global commodity prices. These days, Minnesota farmer Matt Romsdahl’s computational skills—he has a math degree from Augsburg College in Minneapolis—are proving especially handy.

Romsdahl, 39, and his wife Britta are relative newcomers to farming. Fifteen years ago, they took out an operating loan to start growing corn and soybeans near St. James in the southern part of the state. Since then, every harvest has been a time of reckoning when the Romsdahls faced the prospect of losses eroding the equity they had built up in the farm.

For much of their tenure, good harvests combined with relatively high crop prices generated sizable profits, and the Romsdahls invested the proceeds in additional grain storage and new barns to raise pigs. But crop prices turned south in 2013, and continued low prices have led Romsdahl to draw upon his math acumen like never before.

He has jumped at any chance to earn a few more cents per bushel, using risk-management tools such as forward pricing—contracting to deliver grain at a future date—to lock in a profitable or at least break-even price.

And the Romsdahls have cut back spending, for both farm operations and family living (they have four preteen children). “Obviously, you look twice before you spend any money. You try to cut fertilizer costs or seed costs; maybe you don’t buy equipment you thought you were going to. We’ve always tried to be pretty frugal with our family living budget and save money where we can,” Romsdahl said.

The family hopes to eke out a slim profit from last fall’s harvest, a disappointment after healthy returns the year before. But Romsdahl believes he’s faring better than many farmers. At his local bank, “there’s a lot of talk about guys they are a little more worried about. I don’t know if I’m one of the exceptions to what’s going on out here; maybe I am.”

For agricultural producers across the Ninth District, this has been the winter of their discontent. After reaping handsome profits earlier in the decade, producers are reeling from lower crop and livestock prices, the result of several years of high commodity production worldwide and a strong U.S. dollar that has limited farm exports.

Many producers in the district are operating at a loss because revenues are not covering their costs. “I’m not sure I want to call it depression, but we’re getting into probably what is the third year of a downswing, and certainly there’s concern and anxiety,” said Keith Olander, dean of agricultural studies at Central Lakes College, a community and technical college in north-central Minnesota.

Farmers are adapting to market conditions as best they can, trimming spending and exploring ways to boost income, including seeking out higher-paying customers, growing alternative crops and working off-farm jobs.

The pain in farm country extends to agricultural suppliers and service firms such as farm implement dealers and manufacturers, which have retrenched and laid off workers.

The downturn in the farm economy has raised the specter of the 1980 farm crisis, when low commodity prices triggered widespread foreclosures of debt-laden farms. But at this point, a reprise of the 1980s appears unlikely because market conditions are different and district farms are on average larger and better capitalized today.

Swing high, swing low

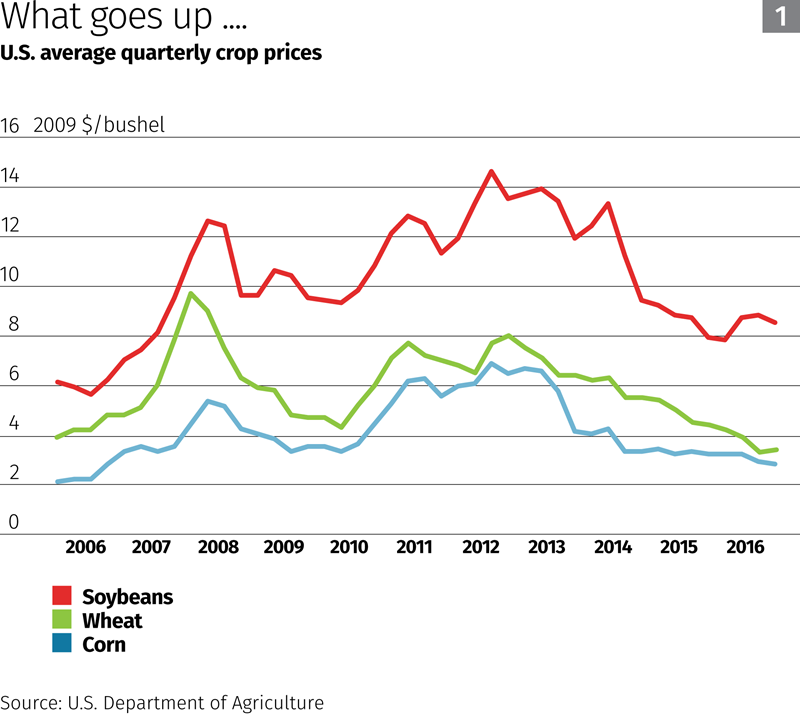

A few years ago, farm fortunes were riding high in the district and across the nation. Instead of looking for ways to economize, spending to expand operations and capitalize on high prices was the order of the day. In 2007, U.S. crop prices rose due to rising domestic and overseas demand that outstripped farm output (see Chart 1). Inflation-adjusted prices for corn and soybeans peaked in 2012, when a drought stunted harvests in much of the Midwest.

“Farmers made money and farmers, sometimes to a fault, like to reinvest in their business,” said Mark Holkup, a farm management instructor at Bismarck State College in Bismarck, N.D.

Producers bought or rented more land to increase production, purchased new machinery and built additional grain storage and other facilities. Low interest rates encouraged borrowing for both farm improvements and family expenditures such as home remodeling, new vehicles and vacations.

But since 2012, crop prices have been on a downward slope because for most commodities, production has caught up with and surpassed demand.

Last fall, U.S. farmers hauled in a bumper corn and soybean harvest, the fourth record or record-tying harvest in a row, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Responding to higher prices, producers have put more acres into production, and favorable weather has boosted per-acre yields. Most of the world’s agricultural regions have also seen bountiful harvests in recent years, contributing to ample worldwide grain reserves.

Global consumption of district farm mainstays has failed to keep up. Domestic corn use for ethanol production has been relatively flat since 2011, and growth in demand for U.S. grain has slackened in regions of the world with slow-growing economies, such as western Europe and Central America.

A strong U.S. dollar, which makes American goods more expensive abroad, has also depressed foreign demand for U.S. farm products and prices received by farmers. The Wall Street Journal Dollar Index, which tracks the performance of the dollar against a basket of foreign currencies, has risen about 20 percent since 2013. U.S. crop prices are lower today than they would be if the dollar were weaker, stimulating foreign sales, said Frayne Olson, a crops economist and marketing specialist at North Dakota State University (NDSU) in Fargo. “Another way of saying it is that we’ve had to discount our prices more heavily to maintain or re-establish our exports.”

The robust dollar has affected prices of some farm commodities more than others. In 2015, 57 percent of wheat grown in the district (and a similar share of wheat produced nationwide) was exported, compared with 52 percent of district soybeans and just 15 percent of corn, according to the USDA. Competition in global wheat markets from countries such as China, India and Ukraine makes American wheat especially sensitive to exchange rates.

The combination of large harvests, cooling demand and export challenges has been a perfect storm for crop producers. “That’s why you’ve seen this dramatic shift” in prices, Olson said. “On the way up, everything came together to cause this rapid acceleration, and now all the major factors that caused that acceleration have flipped on us, and we’re seeing this rapid decline.”

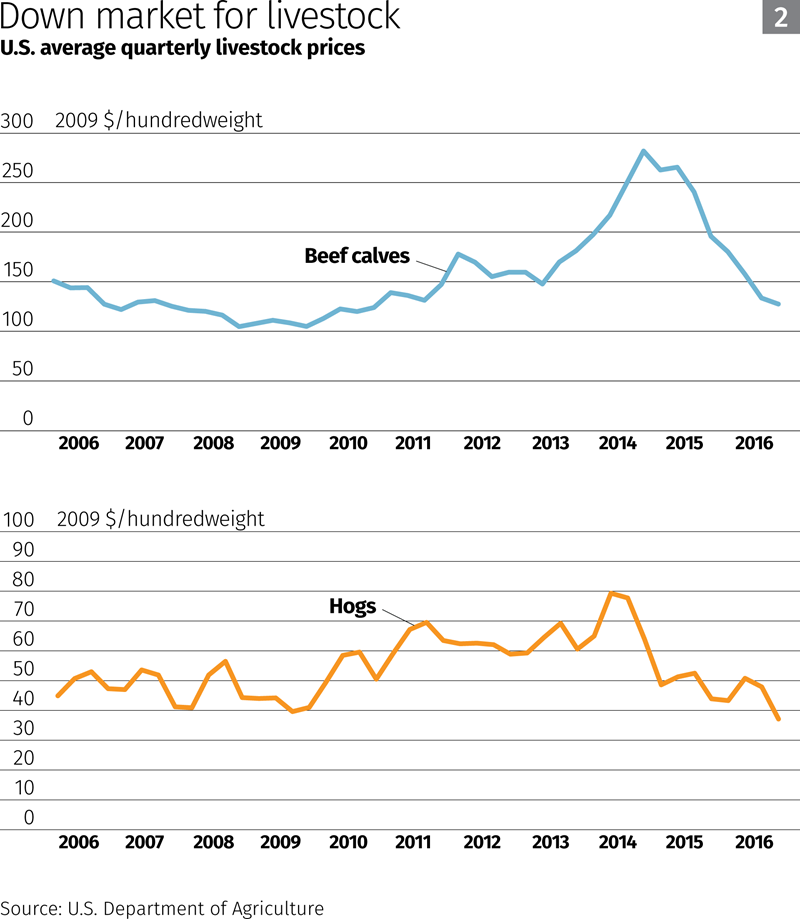

Lower prices for soybeans and corn, chief ingredients in animal feed, have benefited livestock producers. But since 2014, when beef calf and hog prices peaked at the highest level in at least a decade (Chart 2), a meat glut has driven down livestock prices. Hog prices fell by more than half in real terms from the summer of 2014 to the end of 2016. Milk prices have also dropped sharply over the past two years, although prices recovered slightly late last year and are projected to rise somewhat in 2017.

The impact of these changes has rippled throughout the district’s ag sector, upending the balance sheets of producers and their suppliers and, in some instances, endangering livelihoods.

Battling to break even

Ag producers are absorbing the brunt of the sea change in market conditions. Romsdahl’s Minnesota farm made a solid profit in 2015; he had sold most of that year’s crop on forward contracts back in 2013 and 2014, when corn and soybean prices were higher. Slumping prices since then determined a very different outcome for the 2016 harvest. “I’ll be close to the black, or in the black,” he said, depending on the price he can get for corn that remains unsold.

Roughly 900 miles to the west, Lyle Benjamin and his wife Adele expect to make little or no profit on the barley, canola and other crops they plan to plant this spring on their farm near Sunburst, Mont. Crop prices are just too low, Benjamin said. “The last two years, we’ve been able to project breaking even or making a reasonable profit,” he said. “This year, we’re going to be right at break-even, even on our highest-value stuff.”

In 2016, revenues were down 30 percent from the farm’s peak sales in 2013, and the Benjamins lost about $26,000 on their wheat crop.

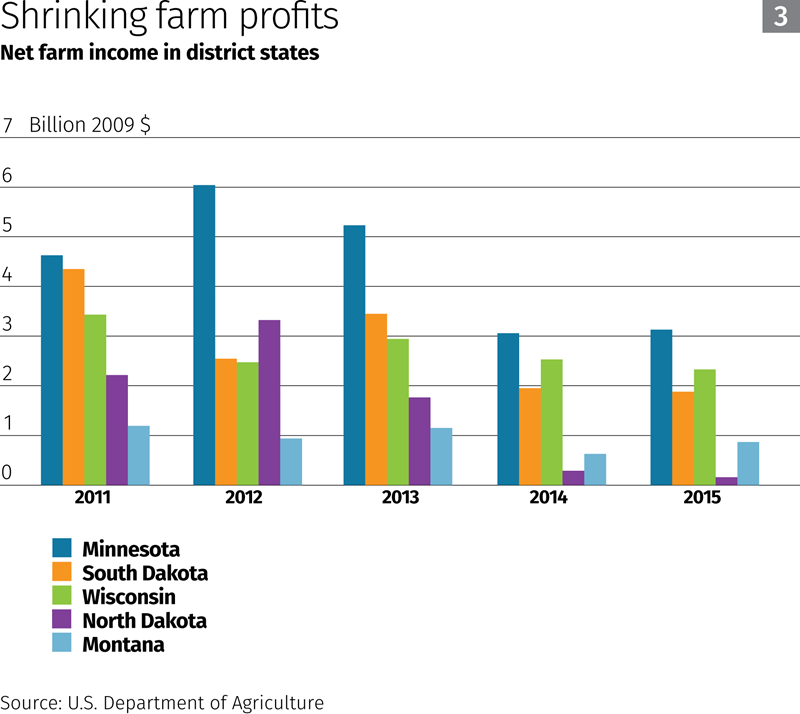

Myriad similar financial outcomes in ag country have resulted in sharp annual declines in net farm income. Nationwide, farm profits fell 13 percent from 2014 to 2015 and were projected to fall 17 percent in 2016 when all USDA data were in. In the district, farm income fell in all five states (excluding the Upper Peninsula of Michigan) from 2013 to 2015, the latest year for which state-level data are available (see Chart 3). North Dakota farm profits plummeted 91 percent over that period.

In many areas of the district, abundant yields in recent years have partly offset lower revenues due to falling crop prices. Holkup says per-acre crop yields for soybeans, corn and sunflowers were “phenomenal” in south-central North Dakota last fall, although wheat yields were less impressive.

Montana has also seen high crop yields, said Lola Raska, executive vice president of the Montana Grain Growers Association. “The thing that has saved a lot of our farmers is that we’ve had two years in a row now of good production. It’s all about revenue, and you can achieve revenue through either price or yield.”

But Raska added that “there are certainly farmers who are really struggling with this recent decline in prices.” Many Montana wheat growers are receiving payments from the federal Price Loss Coverage program, which compensates enrolled farmers for revenue losses due to low prices. Typically, the payments allow farmers to cover their expenses for the previous crop year.

Livestock and dairy producers are also burdened by low prices, despite lower prices for animal feed that have cut production costs.

In South Dakota, high hog prices owing partly to a virulent disease that decimated pig barns nationwide in 2013 led producers to enlarge their herds. The state’s supply of hogs ready for slaughter increased 15 percent from 2015 to 2016, according to USDA figures. Today, in a buyer’s market for pork, “the majority of our producers are operating at a loss,” said Glenn Muller, executive director of the South Dakota Pork Producers Council.

For Wisconsin dairy farmers, “breaking even is a goal for many, and some are not,” said Tim Trotter, executive director of the Wisconsin Dairy Business Association, an industry trade group.

For all types of producers, the financial strain is particularly severe for less-established operators like Romsdahl and Benjamin, who is also 39—relatively young for a farmer (in 2012, the average age of U.S. farm operators was 58, according to the Census). Younger farmers, many of whom were drawn to farming by high crop prices, are more likely than their elders to rent land and to incur debt to buy new machinery and cover operating expenses.

“They’re maybe a little more highly leveraged, a little less financially able to weather some of these downturns,” Raska said. “We need younger people to come into the industry, but it’s hard for them.”

Tightening belts

Farm costs have risen in recent years in response to the runup in commodity prices, which increased demand for farm inputs and so raised prices for everything from land to fertilizer to fencing. Those costs have been slow to adjust to lower crop and livestock prices, putting extra pressure on farmers’ profit margins.

Almost universally, district producers have reacted to income loss by cutting their expenses down to size. “Farmers are tightening their belts all over, just trying to find a way to make it through,” Trotter said.

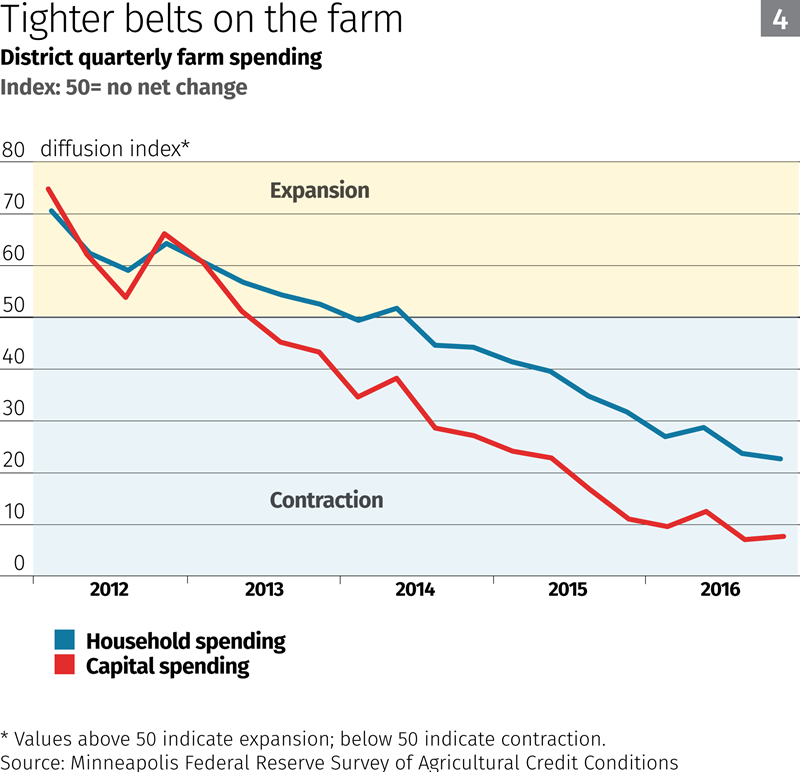

Nationally, annual spending by ag producers has declined since 2014, paralleling the drop in farm income. From 2014 to 2015, capital investments by U.S. farms fell by one-quarter, according to the USDA, and were projected to stay virtually flat in 2016. Annual surveys of agricultural credit conditions in the district by the Minneapolis Fed show a similar pattern, with a sustained decline in both capital outlays and spending by farm households over the past three years (Chart 4).

Farmers have put off purchases of big-ticket items such as pole barns, combine harvesters and tractors, opting to repair rather than replace or buy used instead of new. “We don’t buy new vehicles, because we just can’t afford it,” said Eric Leritz, who raises Angus cattle on his farm near Park Rapids, Minn. He said he needs a new hay baler to produce winter forage for his animals, “but I’ll probably have to wait a couple of years on that.”

When commodity prices were high, producers bid up land values and rents in many areas of the district; in Minnesota, average cropland rents increased 40 percent in constant dollars from 2010 to 2014, USDA figures show. Since then, rents have moderated—but not quickly enough for some farmers desperate to cut costs.

Negotiating lower rents can be a delicate matter; pushy tenants risk losing their land to another farmer. But district producers are seeking relief from their landlords; last fall, University of Minnesota Extension presented a series of workshops across the state to help farmers and landlords work out fair farmland rental agreements.

Crop producers are also trying to make do with less fertilizer, seed and chemicals for weed and pest control. More judicious use of fertilizer—varying the amounts applied to different parts of a field based on soil conditions—saves money. And some farmers have opted to buy less genetically advanced, cheaper seed varieties. But producers must be careful about cutting corners on these vital crop inputs, said Olson of NDSU. By skimping on fertilizer or failing to control weeds, “you run the risk of lower yields and shooting yourself in the foot.”

Family living expenses—vehicles, appliances, home remodeling, entertainment—make up a relatively small share of total farm costs, Olson said. But many producers are also striving to economize in this area. For example, Leritz and his wife Janel were considering limiting cell phone service for their four teenaged children. “Cell phones are expensive,” Eric said. “Not every kid needs to have a cell phone.”

Farm-supply woes

Less spending by farmers has in turn forced agricultural suppliers and service firms to cut their own costs and adapt in other ways to an austere economic landscape.

Farm implement dealers that grew accustomed to customers packing into their showrooms to buy the latest models now labor to reduce their large inventories of discounted used equipment. With sales of new equipment down markedly, many dealers in the district have tried to shore up sales by focusing on leasing and equipment repair.

Revenues at Midwest Machinery, a John Deere dealership with 13 locations in central Minnesota, fell 40 percent from 2014 to 2016. But increased equipment leasing—a less common dealer practice before the farm downturn—helped the firm squeeze out a modest profit in 2016. “The farmers right now like the lease option because it removes the risk” of owning equipment that is likely to fetch a poor price in a glutted used-equipment market, said Jacob Bryce, Midwest’s used-equipment manager. Leasing also reduces the upfront cost of acquiring machinery.

Parts and service is another bright spot for the firm; sales have increased 15 percent since 2013 because many farmers are opting to repair their aging machinery instead of trading it in for something new.

Farm implement manufacturers hit by lower nationwide demand for combines, tractors, tillers and other farm equipment have laid off or furloughed workers. Last year, CNH Industrial, which produces equipment under the Case IH and New Holland brands, let go 70 employees at its plant in Fargo, N.D. The move brought to at least 260 the number of workers at the site who have lost their jobs since 2014.

Other implement manufacturing operations in the district that have downsized include Raven Industries, a large employer in Sioux Falls, S.D., North Dakota tillage equipment manufacturer Wil-Rich and a plant in Jackson, Minn., owned by Georgia-based AGCO Corp.

Elevators that handle grain for producers have trimmed their profit margins in an attempt to hold onto customers. Low crop prices that induce farmers to shop around for cheaper storage and routes to market have “put pressure on elevators to try to attract business, be as competitive as they can,” said Bob Zelenka, executive director of the Minnesota Grain and Feed Association, which represents over 250 grain elevators and feed mills in the state.

An analysis of the impact of reduced farm spending on broader local and state economies is beyond the scope of this article, but there’s evidence that in ag-dependent areas of the district, farm troubles are spilling over onto Main Street and government balance sheets. In South Dakota, state revenues for the upcoming fiscal year were $26 million lower than projected last fall, in part because of a drop in tax receipts from farm machinery sales; from 2013 to 2016, collections fell by half.

Communities in north-central Montana’s Golden Triangle are feeling the strain of a third year running of low wheat prices, said Miles Hamilton, president of Havre-based Independence Bank, a community bank with branches in Conrad and four smaller towns in the region. “There is an impact on Main Street, clearly,” he said. “Ag is what we do; it’s big.”

Hamilton said that local auto dealers were selling fewer trucks, and at a Havre western-wear store, holiday-season sales last year were 60 percent below levels typical a few years ago.

Shrewd marketers

Cost cutting isn’t the only way producers are adapting to low commodity prices, although market conditions and the nature of farming often limit their options.

One strategy being pursued by farmers is to take advantage of often fleeting opportunities to garner a higher price for their production.

The prolonged downturn has made hedging tactics such as forward pricing less effective; it makes little sense to lock in crop or livestock prices that are currently below the cost of production. But a producer may be able to sell to a local or regional buyer for a higher price than prevailing prices on national commodity exchanges. For example, a farmer may sign a forward contract with an ethanol plant that is willing to pay a premium for corn delivered in the spring, when the plant anticipates ramping up production to meet demand for ethanol to blend with gasoline.

“We’ve got some pretty shrewd marketers out here,” said Harold Wolle, president of the Minnesota Corn Growers Association. “They’re going to look for an extra dime or an extra quarter [per bushel] in this market and capitalize when they get the chance, to take some risk off the table.”

In some parts of the district, farmers have turned to alternative crops that command higher prices than traditional crops.

Over the past few years, Benjamin has planted less wheat and more barley, canola and pulse crops such as dry peas and lentils. “The market’s been telling us it doesn’t want wheat, and we’ve been listening to that signal,” he said, adding that he wasn’t planning to plant any hard spring wheat this spring.

But his farm receives greater annual rainfall than other parts of the wheat-growing Golden Triangle. The climate in much of the region is unsuited to growing pulse crops and other alternatives to wheat, said Raska of the Montana Grain Growers Association. And existing grain distribution networks are set up to move wheat and barley to market, she said.

Farm families are increasingly reliant on jobs in town to supplement diminished farm income. A wage earner in the family has been a lifeline for many families trying to cover expenses such as health care, Wolle said. “If you have a spouse with an off-farm job that provides health insurance, that goes a long way toward reducing the amount of money that the farming operation has to kick in for family living expenses.”

The Romsdahls’ health care coverage is provided by Britta’s nursing job at Mayo Clinic Health System in Mankato.

In the Leritz family, Janel also works in health care, as a personal care assistant. And Eric works part time off the farm, trucking potatoes on contract for mega-potato grower R.D. Offutt Co. “Hauling spuds is a big money generator; it helps make my [bank loan] payments,” he said.

The 1980s revisited?

The downturn in the farm economy has led some commentators to draw comparisons with the 1980s farm crisis. There are parallels between today’s market conditions and those at the beginning of the period when thousands of farmers nationwide went bankrupt and lost their livelihoods. As occurred in the early 1980s, bumper harvests and export constraints slashed commodity prices after a prolonged runup in prices had induced producers to increase spending and borrowing.

But there’s little indication—yet—that district producers are headed for a reprise of that dark time in agriculture. Farm consolidation followed the 1980s crisis, and district farms today are on average larger, more efficient and better capitalized than 35 years ago. Land values are higher and interest rates much lower, allowing producers to support more debt. And lenders have become adept at working with farmers to help those in trouble make it through to the next harvest (see A call to action for community banks).

Nevertheless, “for the farmer that goes broke, it will be the ’80s all over again,” said Olander of Central Lakes College. So far, farm exits by cash-strapped producers have been rare in the district, but Wolle and other sources said it’s likely that some older farmers have chosen to give up the farm and retire rather than keep battling low prices. Prospects for a turnaround in farmers’ fortunes depend to a large extent on the trajectory of commodity prices this year. A recent uptick in soybean prices due to relatively strong exports has heartened crop farmers like Wolle, who plans to capitalize on the market shift by planting more beans than corn this spring. Dairy farmers were also hoping that a modest rebound in milk prices since last fall means that they “can begin to see the light at the end of the tunnel,” said Trotter of the Wisconsin Dairy Business Association.

The price outlook is less sanguine for other commodities, including beef cattle. Holkup observed that ranchers in drought-prone western North Dakota are “a resilient bunch … but it’s going to be a couple of tough years on the livestock side.”

As winter rolls into spring, district ranchers, farmers and businesses that depend on their spending are cinching their belts a bit tighter and keeping a weather eye on the market horizon. Olson foresees “rapid price rallies” and improved profit margins for U.S. producers if production falters in other parts of the world, reducing global reserves of commodities such as corn, soybeans and wheat. But when and where crops will fail and what commodities will be affected “is the unknown part of this,” he said.

Much is unknown for producers trying to make the best of challenging market conditions, Olander said. “They’re wondering, ‘What do I do in 2017 that’s going to be different and allow for profitability?’ We don’t know that. Nobody’s got that answer.”