Video: fedgazette editor Ron Wirtz on upward income mobility

The Quick Take: Upward income mobility—children faring better financially than their parents—is widely believed to be stagnant, even decreasing in the United States. New research by a team of academics has found that, in fact, the American dream is still alive, but achieving it depends heavily on where you grow up.

In large swaths of the country, upward income movement across generations is low. But if you live in the Ninth District, statistically speaking, you’re more upwardly mobile than people living elsewhere in the country. The reasons for this are hard to pinpoint, but appear to stem, at least in part, from comparatively better education outcomes, greater family stability, strong local economies that foster a larger middle class and access to good-paying jobs, whether in oilfields or in larger cities where wages are higher. In rural areas, the strength of the farm economy—as well as its cyclicality—also appears to play a role in improving the fortunes of children compared with their parents.

Few notions are as ingrained in the national psyche as the American dream—the idea that kids will be better off than their parents and that anybody can make it to the top in this country with a little grit, determination and hard work, no matter their starting place on the ladder.

But there is national hand-wringing over the state of the dream—a victim of income inequality, a sluggish economy coming off a horrendous recession or sundry other factors. A Wall Street Journal/NBC poll in early August found that “Americans are registering record levels of anxiety about the opportunities available to younger generations.” A CBS poll in early summer reported that almost three in five believed that “the American dream has become impossible for most people to achieve.”

Bruce Vold, pastor, Trinity Lutheran

Church, Carrington, N.D.

Photo by Layne Kennedy

Bruce Vold has a multigenerational perspective on the matter. The pastor at Trinity Lutheran Church in Carrington, N.D., he’s a third-generation churchman who has lived the American dream even if that was never the goal. Vold’s pastor grandfather was paid “in chicken” in the 1930s—rather than receiving a salary, parishioners would give him chickens or “a cow for milk for a family of seven. They had nothing,” Vold said. But each successive generation has attained a higher standard of living.

Vold and his wife, Anne, have three children: two out of college and one still attending. “Certainly, we wanted them to have professional success,” said Vold. “But I didn’t care what they did. ... I’m looking more for how they are contributing to society.”

Nonetheless, the young Vold clan appears poised to continue the sought-after American dream of moving up financially. Middle child Matthew has a business degree and works at Dakota Growers, a large pasta plant in his hometown. Daughter Kelly is studying dentistry at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minn.

Eldest son Bryan is an accountant in Minneapolis. He also attended Concordia College, and “didn’t have a clue” about what he wanted to be until he took a sophomore class in accounting in 2006. With the Great Recession looming, “accounting looked like [a career that] I should be able to get a good job in,” he said. He was right, landing a position at tax and audit giant Grant Thornton before the start of his senior year. After five years, he now makes about $70,000 annually.

Regarding his financial prospects, “I always felt I would do better” than his parents in terms of income, but not because of a poor upbringing, said Bryan. Growing up, “we didn’t lack for anything, but there wasn’t any excess.”

The Vold kids also heard about the importance of going to college—not so much for careers and big money, but to obtain a broad world view and “to learn how to learn,” said Bruce Vold. “I think I’m a frugal person and try to be wise about things and feel good about getting my kids through college. ... But they are going to do better financially.”

One family’s story cannot capture the national experience when it comes to intergenerational income mobility—how kids fare financially compared with their parents. But reports of the death of upward income mobility in this country may be exaggerated. Groundbreaking research by a group of academics has found that, in fact, the dream is quite alive in the United States.

However, the research also unearthed a major caveat: It matters where you grow up. In large swaths of the country, upward income mobility is low. But if you live in the Ninth District, statistically speaking, your upward mobility is much higher and rivals anywhere in the country. The reasons for this are hard to pinpoint, but appear to stem, at least in part, from comparatively better education outcomes, greater family stability, strong local economies that foster a large middle class and proximity to and availability of good jobs in oilfields and higher-paying metro areas. In rural areas, the strength of the farm economy—as well as its cyclicality—also appears to play a role in how children do financially compared with their parents.

That’s not to say that everyone, everywhere in the Ninth District is upwardly mobile. Some places, particularly Indian reservations, continue to experience generational poverty and income stagnation. But even these places have a unique story to tell regarding the quality of life where people call home.

The research base

Recently, a group of academic researchers led by Raj Chetty of Harvard University released a comprehensive study on the intergenerational income mobility of poor families nationwide. (See Chetty, Hendren, Kline and Saez 2014. NBER Working Paper 19843.) All of the data in this study were made public, serving as the foundation for this fedgazette analysis.

The research—which has evolved into an ongoing study called the Equality of Opportunity Project—looked at the incomes of children from the poorest families to see how these children later fared as 30- to 32-year-olds. Subjects in the study, who were identified anonymously through federal tax records, were then grouped into commuting zones, or clusters of counties with strong commuting ties that serve as a rough proxy for regional economies nationwide. (For more on the study’s methodology, see “And now, a word from our sponsor.”)

The study found that upward income mobility, while generally lower in the United States than in many developed countries, hasn’t changed much. But the researchers found major differences in income mobility depending on where children grew up. In Atlanta, for example, only 4.5 percent of children from households in the lowest 20 percent of income can expect to be in the top 20 percent as adults. In Rochester, Minn., and Fargo, N.D., it’s 14 percent, which compares favorably with high-mobility countries around the world.

“We actually came in just asking a simple question of whether the American dream is still alive and whether the U.S. is a land of opportunity, and what we found is that that question really doesn’t have a straightforward answer because the answer seems to depend very much on geography. That is, it depends on where you grew up,” said Chetty earlier this year in St. Cloud, Minn., where he was giving a speech at St. Cloud State University. “In some parts of the U.S., kids who grow up at the bottom of the income distribution, in disadvantaged families, end up having very high chances of moving up ... and in other places the American dream doesn’t seem to be nearly as alive.”

Enter the Ninth District, where adult children in the study scored much higher on two fundamental measures of income mobility analyzed by the fedgazette: absolute upward mobility and bottom-to-top mobility (see maps with related mobility definitions). This performance was not a methodological quirk—something driven by, say, the Bakken oil boom and a red-hot North Dakota economy. Every district state outperformed the nation as a whole in both measures, often by considerable margins.

s

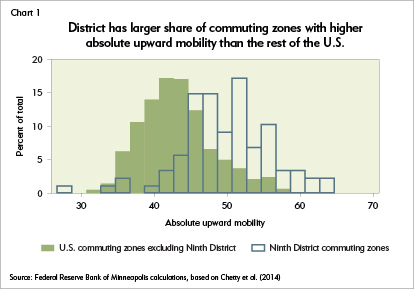

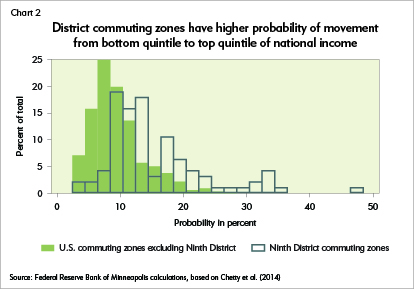

For absolute upward mobility, the distribution of the district’s 87 commuting zones shifts far to the right, or up the income mobility ladder, compared with 622 other commuting zones across the country (see Chart 1; due to small samples, a number of commuting zones in the nation and district had no rank and are not included here). At the same time, the chances of going from rags to riches—from the bottom quintile of income to the top—were also higher in the district (see Chart 2).

We’re #1 (through #6)

The district is home to many of the nation’s highest income mobility commuting zones. North Dakota alone grabbed the top six scores in absolute upward mobility in the country, and seven of the top eight. Two of these are located in the western oil patch, a region that has seen unprecedented income gains over the past decade. But the other five are rural commuting zones located outside the Bakken region.

Related content

And now, a word from our sponsor

Calling home

Despite low upward mobility on many reservations, more Native Americans are calling them home, where culture often comes before commerce

Hunting for economic development

Both opportunities and obstacles abound on reservations looking for more economic activity

One of them is the Carrington area, home to the Volds, located in the heart of the state and encompassing Foster and Eddy counties. The commuting zone is ranked eighth nationally in absolute upward mobility, but doesn’t necessarily look or feel rich in the way you might expect in a place reported to be upwardly mobile. Until about 2010, the city’s population had been in gradual decline and has increased by only a few dozen people since then, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Homes lining the streets, and the vehicles plying them, are like a new pair of comfortable shoes: nice, functional, but not gaudy. There is wealth in the community, numerous sources said, but it is not often publicly displayed.

Income mobility rankings by the Chetty research team do not solely depend on the net change or difference in the income of children versus that of parents (see methodology sidebar). Nonetheless, income gains are a decent predictor. In Foster and Eddy counties, for example, annual median income for the adult children rose to $61,500, up from $53,000 (inflation-adjusted) for their parents.

Carrington, which sits at the intersection of two major state highways, feels like a city of more than 2,100 people. There’s a new hotel in town, and Central City Grain is erecting an 820,000-bushel steel bin to match the slightly smaller one it put up two years ago. The streets in many places are a mess—not because of neglect, but because they are being torn out and replaced, thanks to a new 1 percent increase in the local sales tax. The city boasts 50 to 60 job openings, and that’s only the advertised jobs.

Vold said the growing affluence in the community can be seen in the parking lots. “We’re not in the suburbs of Minneapolis or St. Paul or wherever ... but the number of newer pickups that kids drive and park in the school parking lot” seems to be growing, he said.

On a map, Carrington is an island in a sea of agriculture, 45 minutes by car from Jamestown (pop. 15,000) and two hours from Fargo, Bismarck and Minot. That seeming isolation has its advantages. Two decades ago, the city beat out almost 30 other communities competing for the Dakota Growers plant, which employs about 200. The community’s central location and its good highway and rail access were factors in the firm’s decision to build in Carrington.

Today, Agro-Culture Liquid Fertilizer is building a new plant in Carrington “because they can distribute to a four-state area from here and save themselves a lot of money,” said James Linderman, Carrington economic development director. “So that’s been a really big help for us—our geographical location within the state and what’s around us.”

Don’t forget the big cities

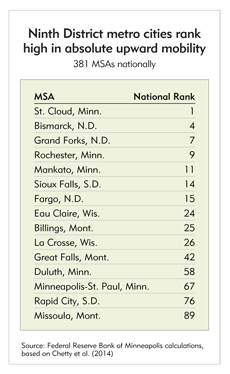

Larger cities in the Ninth District also fared well among their peers. St. Cloud scored highest among 381 metropolitan statistical areas nationwide in absolute upward mobility; several others were in the top 25, and all 15 MSAs in the district ranked in the top quartile (see table).

These results were something of a revelation to some observers, such as King Banaian, a St. Cloud resident and state representative in the Minnesota House. “It did surprise me to some extent,” he said. Nonetheless, Banaian had no problem offering possible explanations for the ranking, in part because he’s an economist and interim dean at the School of Public Affairs Research Institute at St. Cloud State University (SCSU) and co-author of the St. Cloud Quarterly Business Report.

St. Cloud might not have the upper income potential of the Twin Cities, he said, but the city has always had good places to work. The region has a higher-than-average percentage of manufacturing jobs, at 15 percent, and many are in high-value sectors like technology and precision instruments.

King Banaian

While the region has lost manufacturing jobs, the overall rate of job loss from 2003 to 2013 (6.5 percent) was significantly lower than the statewide average (10.8 percent) over this period. At the same time, the area has seen strong growth in other sectors like health care. The region is a medical center for much of the north-central part of the state, Banaian noted.

Banaian also believes that St. Cloud’s proximity to the Twin Cities, roughly an hour away, is a big reason for the ranking. Minneapolis-St. Paul is a big draw for St. Cloud residents. That matters because the Chetty research team assigned all income of the adult children to their home commuting zone when they were 16 years old. So in the study’s statistical framework, St. Cloud children who left home for the bright lights of Minneapolis nonetheless had their paychecks attributed back to their home commuting zone.

“We’re just a way-stop to the Twin Cities,” Banaian said. “Our number one export is smart kids.” The department recently found that of roughly 700 alumni, 400 lived in the Twin Cities. “Most probably went down there to earn more money than they could get here.”

Many sources in other communities similarly acknowledged that their sons and daughters had gone elsewhere to make their living, very often to larger cities that historically have paid higher wages, thus offering a better opportunity to surpass mom and dad’s income.

Vold is not even the sole pastor at Lutheran Trinity whose children went away for college and later found good jobs in bigger cities. His colleague, Russ Christiansen, grew up 35 miles away in the little town of McHenry. He and his wife of 38 years have two kids; a daughter lives in South St. Paul, Minn., and does administrative work out of her home for a hospital based in Duluth. Their son works in Fargo for Microsoft and “earns more than my wife and I together,” said Christiansen.

Of course, no community keeps all of its own, and young adults from every community move away to find their fortune. But higher upward mobility in the district might also be related to comparatively high college attainment in district states; North Dakota and Minnesota rank among the top seven states for percentage of adults ages 25 to 64 with an associate’s degree or higher, and South Dakota and Wisconsin are above the national average, according to Census figures. Such attainment makes it more probable that hometown kids will land higher-paying jobs in professional fields, whether at home or elsewhere.

In Carrington, “I see the expectation of the student [to achieve] from the parents, from the community, from the school,” said Brian Duchscherer, superintendent of Carrington Public Schools. He said that 86 percent of the high school class of 2013 had plans to pursue two-year or four-year degrees. “Combine that with the economic climate in North Dakota right now ... [and] I think it’s the perfect storm when those two meet.”

More on why and how

Ultimately, the factors behind intergenerational income mobility are many and vary by location. But it’s not hard to infer why some commuting zones have high income mobility.

For example, the commuting zone of Dickinson, N.D.,—which includes the counties of Stark (home to Dickinson), Billings and Dunn—has the highest absolute upward mobility ranking in the country. While there is no irrefutable proof, its location in the Bakken oilfields likely plays a considerable role in its high rank.

In 2013, for example, 47 percent of the 22,000 jobs in Stark and Dunn counties, and 67 percent of income earned, were related to the oil and gas industry, according to a recent report by Job Service North Dakota. (Figures for much smaller Billings County were unavailable.)

In the Chetty study, average annual income for adult children in the Dickinson commuting zone was almost $76,000 in 2011-12 (current dollars); that compares with about $65,000 for parents in this zone (1996-2000 average, adjusted for inflation to 2012 dollars).

But in other places, as well as more broadly across states, teasing out the reasons for high or low upward mobility is a very complex task because a multitude of economic and social factors influence income over generations. Rank could even be influenced by methodology.

Robert Johnson, professor and chair of the Ethnic Studies and Pre-College departments at SCSU, suggested to Chetty after his speech in St. Cloud that the city’s top ranking in absolute upward mobility among MSAs might be influenced by the timing of the parent sample. By choosing to study children born in 1980 to 1982 and measuring income of the parents in the latter half of the 1990s, the St. Could population sample “at the time, would have had low ethnic and minority populations,” who typically fared worse on mobility measures nationwide.

Over the past two decades, St. Cloud has seen a considerable increase in immigrant—particularly Somali—and domestic minority populations, according to Johnson. Whether these new St. Cloud residents will experience similarly high mobility, “you’ll have to wait another 10 to 15 years for those results.”

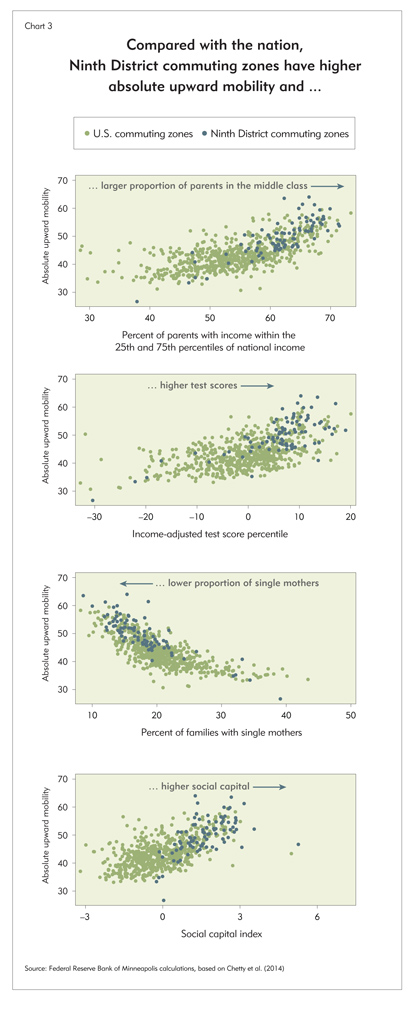

While the Chetty research team did not specifically factor for demographic changes in local population samples, it did investigate a number of variables looking for correlations to mobility—not causal proof, but evidence that the presence (or absence) of a particular factor was common to those with high (or low) upward mobility. Among almost three dozen variables studied, five stood out for having a significant correlation with income mobility: residential segregation, size of the middle class, K-12 test scores, social capital and single parenthood.

As one might expect given their high mobility rankings, Ninth District commuting zones generally outperformed the nation on these measures. Residential segregation, which includes income and racial segregation, is lower in many district communities. This might be partly due to the fact that many district commuting zones are smaller in population (which tends to limit the upper end of the income distribution) and largely white (reducing racial segregation by default).

Other correlations also offer a notable contrast compared with the rest the country. For example, the middle class—defined as the percent of parents with incomes between the 25th and 75th percentile of the national income distribution—is larger in Ninth District commuting zones, while the fraction of children living with single mothers is smaller. As for school performance, income-adjusted school test scores in English and math for children in third through eighth grades tend to be uniformly higher (see Chart 3).

Ninth District commuting zones also tend to have higher social capital, which the Chetty team gauged through voter turnout, percentage who return Census forms and participation in community organizations. Upwardly mobile St. Cloud offers a good example.

“There is tremendous social capital here. ... People are willing to invest their time, talent and treasure into the community. And you can see it,” said Banaian. He pointed to the renovation of Lake George and Eastman Park near downtown, which had fallen into disrepair. In 2007, the St. Cloud Rotary Club raised over $1.5 million from local businesses and members, which helped leverage a total investment of $7 million to transform the lake and park into a community destination with walking and biking trails, sitting areas, fishing piers, a splash park and meeting facilities.

In 2011, the club started hosting “Summertime by George,” a weekly festival at the park featuring live music, a farmers market, food vendors and family activities. Attendance reached 86,000 people in the summer of 2013, and Rotary members logged 1,500 volunteer hours.

“It’s the biggest thing in town. This is like a party on steroids,” said Banaian. “If you’re looking for anyone on Wednesday night, they are down there.”

Back home on the farm

The Chetty research team looked at only a few isolated factors directly related to local economies, including the share of manufacturing jobs and workforce participation rates, and found no strong correlations. An exhaustive review of other local-economy factors—like employment growth and industry mix—is outside the scope of the project. But there does appear to be one factor—identified by multiple sources and supported by data—that seems likely to have influenced upward mobility rankings, particularly for lightly populated rural areas: agriculture.

In this case, the time frame for measuring the income of parents (1996 to 2000) came when the farm economy in many ag-dependent counties was poor to modest, but was followed by one of the strongest farm economies of recent memory. The ag surge appears to have had significant spillover effects.

For example, the commuting zone of Linton, N.D., includes the counties of Emmons, Logan and McIntosh, with a combined population of just 8,200. The zone ranks second in the country in absolute upward mobility, but that’s not necessarily obvious in the zone’s biggest city—Linton, population 1,100. Broadway Street downtown is active, but also has a few vacant storefronts and has lost some business anchors over the years, according to local sources. The town of tidy neighborhoods and unassuming, well-maintained houses appears content with what it has, rather than dreaming about what it might become.

Without a vibrant farm economy, it’s difficult to see how this commuting zone could be ranked so high, and the study’s timing likely plays a role as well. In the late 1990s, farming in the region was struggling, responsible for just 13 percent of the three-county economy, according the Bureau of Economic Analysis; in 1997, annual net farm income in this region averaged less than $25,000 per farm (unadjusted for inflation), including fairly generous government subsidies, according to the USDA’s Census of Agriculture.

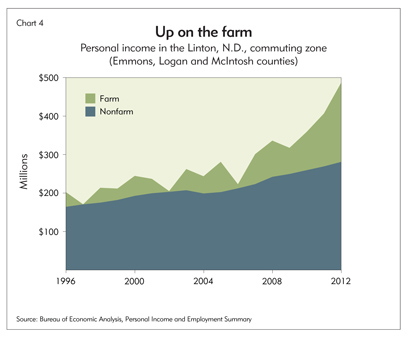

Things didn’t improve quickly, but a confluence of factors over the next decade and a half—rising commodity prices, higher yields from better farm practices and movement to more profitable commodities like corn and soybeans—eventually led to record farm income in the region (and across North Dakota). By 2012, annual average net farm income had risen to almost $120,000 per farm in these three counties, and agriculture’s share of total personal income in this commuting zone leapt to 42 percent (see Chart 4).

Spencer Larson is a recently retired senior farm loan officer for the USDA’s Farm Service Agency in Linton. He came to Linton in 1972 to work for the Farmers Home Administration (renamed the Farm Service Agency in the 1990s). Over a 42-year career, Larson has ridden the agricultural roller coaster with local farmers, including the brutal 1980s, when many farmers went bankrupt.

Things started turning around in the 1990s, Larson said, thanks to more consistent precipitation, better farming techniques and technology. Eventually, farmers started making real money, and some weren’t quite sure what to do, Larson said. “One young farmer said, ‘You know, now that I’m making money, it’s more stressful on my wife and [me] because we have to decide where to spend it instead of giving it all back to the lender.’”

He knows of one young man who came back to the area to farm. “His dad gave him a nice part of his unit to farm, gave him all of the equipment—he just had to borrow money for the inputs and the rent.” Despite fairly high rent that first year, Larson said, “the kid ... hit the crop, hit the price and he was on his way ... from basically nothing to six-figure [net worth]. In less than 10 years of farming, he probably has equity in excess of $1 million today.”

For some, the hardscrabble days seem like ancient history. “I’m on the third or fourth generation of farmers,” Larson said. “The dads that have turned over [operations] to their sons and daughters have said, ‘My kids have never experienced a bad year. I’m worried what’s going to happen when that happens.’ We’ve had no crisis, no severe weather issues, no overall big disasters,” but he added that current low crop prices would be a big test for young farmers.

While farm consolidation continues, new opportunities have opened up in the farm economy, according to Larson and multiple other sources. For example, agronomy—the science and technology of food production and farm management—has brought new companies and jobs to town, helping farmers with soil science, irrigation, weed and pest control, crop rotation and more. Many agronomy jobs involve considerable schooling, bringing jobs for college graduates to many rural communities. “So that’s been a job opportunity that was nonexistent 20 years ago,” said Larson.

Thriving agriculture also offers a chance for sons and daughters to come home. While there are no good data on such matters, local sources suggest that there has been a boomerang effect on young adults. Allan Burke might be called the eyes, ears and mouth of Emmons County. In 1993, Burke and his wife Leah bought the Emmons County Record, the oldest business in the county and the third-largest weekly newspaper in the state. While Burke is semi-retired, he still keeps close tabs on the community as the publisher emeritus.

Before the ag boom hit, “our farmers were aging, and nobody wanted their kids to come back and farm. But now, they want junior to come home ... [and] we have a lot of young couples and young farmers who have come back” to work the land, he said. Burke’s son graduated from high school in 2007 and recently moved to Washington state to teach high school biology—a common move for many graduates in the past. “Nobody stayed around here, or very few,” said Burke. But that appears to be changing. “Now there’s like five or six boys from his class [of about 34] who are farming, and then there’s a couple who are in agronomy.”

Vold has seen the same phenomenon in Carrington. “There was a point in North Dakota [where we said] goodbye to our kids. Graduation felt like a funeral. It was like, ‘Well, nice having you here for these 18 years, and you’re all going to go off and get jobs everywhere around the country,’” said Vold. “Now, we have all kinds of people, young families [coming back]. Many of them are farming, but [there are] also a lot of other choices. We have three excellent doctors in our clinic and three physician assistants, and they’re all from here.”

Vold’s middle child, Matthew, “grew up here, went off to college, came back, and he’s got a good job” in the business office at the pasta plant in town. Just 26 years old, “he bought a house here in town. Doing better that way than I was” at that age, Vold said.

Though Vold’s older son, Bryan, said he enjoys living in the Twin Cities, he hasn’t dismissed the idea of coming home. “I definitely have not ruled it out.” Bryan Vold is single right now, but if he were raising a family, he said, “I would rather do it in Carrington. It just feels better.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.