Video: fedgazette editor Ron Wirtz on low income mobility

The Quick Take: Upward income mobility is very high across the Ninth District, but very low in some places, most of which have a large Indian reservation. These places have struggled for years with low income, high unemployment and poverty, and high rates of violence and alcohol and drug abuse, among other things. But reservation populations appear to be growing—modestly by official count, but faster according to tribal sources. That tribal populations appear to be growing at all, given the struggles of reservation life, suggests that there are important, nonfinancial reasons why people live where they do in spite of circumstances that appear not to be in their best economic interest. Anecdotes from tribal members returning to their place of birth are a signal that something besides income and financial opportunity influence where some people choose to live and raise their families.

Maps are very confident things.

They tell you specific facts about geography, the people living in those places, and the economy coursing over the land and through the lives of these people. Maps are great for innumerable comparisons, offering demarcations with little wiggle room: You are here or there, this or that, one or the other and never both.

Recent research on intergenerational upward income mobility—a geeky phrase for how well kids do financially compared with their parents—puts much of the Ninth District on the proverbial map for having some of the highest upward mobility in the nation (see cover article). These data suggest that the American dream is more alive in the Ninth District than virtually anywhere else in the United States.

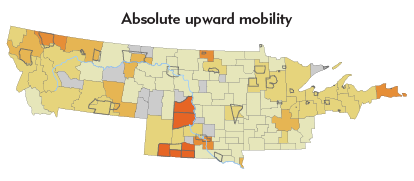

But not everywhere in the district, mind you. Income mobility maps show—indeed, highlight—that some of the places with the least upward mobility are also in the Ninth District (see map). Virtually all of these places have large Indian reservations. The region that includes the Rosebud Reservation, home to the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, has the dubious distinction of having the worst upward mobility rank in the country.

If the American dream means doing better than your parents, or going from the bottom floor to the penthouse, the map implies that achieving the dream also means leaving the reservation.

But go to the Rosebud Reservation in south-central South Dakota, or to the Cheyenne River Reservation to the north, and a story emerges that doesn’t always fit the income mobility map. Rather than emptying out, reservations appear to be growing, luring back members who were pursuing the dream somewhere else, only to decide later that they wanted something else they could get only on the reservation.

A decade ago, Ann-erika White Bird and her husband, Josh Dillabaugh, were living in Denver after they both earned bachelor’s degrees at the University of Colorado in Boulder. She was a paralegal at a civil rights law firm, Josh worked construction and they enjoyed the city, she said. They were making good money and started a family, having a daughter and then a son two years later. Then the recession hit, and Josh’s work became more sporadic. Coupled with the costs of raising children, owning a home and city life in general, the downturn got them thinking that maybe city life wasn’t for them anymore.

“The only reason to be in the city is to make money. I mean, there’s opportunity, [but] if you can’t build a life and you’re just living from paycheck to paycheck, go home. That’s why we came home,” said White Bird, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. (Her husband is a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.) So three years ago, they packed up the family and moved to the Rosebud Reservation.

Ann-erika White Bird, her husband Josh Dillabaugh, daughter Osina and son Josh Dillabaugh II

Photo by Layne Kennedy

White Bird is now a part-time instructor in foundational studies—reading and writing—at Sinte Gleska University in Mission, S.D., in the heart of Rosebud. She also put her English degree to work by starting a news blog called Lakota Voice, covering tribal governance and politics. Josh works construction in the area.

Their income is a fraction of what it used to be, and the transition to the reservation wasn’t flawless. But their children, now ages 6 and 4, “acclimated really quickly,” said White Bird. “It was really great because we wanted the kids to have the kind of imagination that we had” playing outside and improvising toys from sticks.

Make no mistake, the income mobility maps don’t lie. Economically speaking, life is a struggle for many on the reservation. Educational attainment is low; unemployment, poverty and suicide rates are high. Housing is often in short supply and subpar. Jobs in the private sector are scarce; well-paying jobs in tribal government are more numerous, but can be difficult to get without a family connection, according to numerous sources.

But the maps are incomplete, two-dimensional fact sheets that lack descriptive depth and nuance about why people live where they do despite challenging circumstances in some cases. The fact that some—possibly many—tribal members return to their place of birth is a sign that something besides income and economic opportunity influence where people choose to live and raise kids.

Income immobility

A team of researchers from Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley, investigated the intergenerational income mobility of parents and their adult children across the country. Parent household income was measured in the late 1990s, and child household income was measured in 2011 and 2012 when children were in their early 30s. The research team organized households and their income by commuting zones—a multicounty designation that serves as a rough proxy for local economies, including rural ones like those on reservations. (For more discussion of research methodology and definitions of income mobility, see the cover and sidebar articles.)

Related content

Hunting for economic development

Both opportunities and obstacles abound on reservations looking for more economic activity

Movin' on up

New research suggests that intergenerational income mobility is high in much of the Ninth District, and the reasons are both obvious and subtle

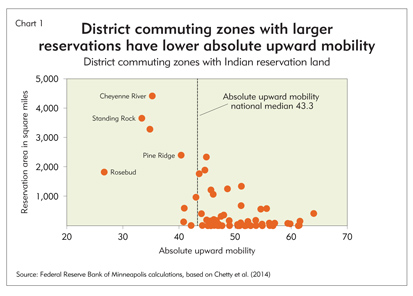

The research shows that commuting zones with the least upward income mobility in the Ninth District typically have a sizable reservation within their borders. Of the 709 commuting zones analyzed nationwide, four zones in the Dakotas with huge reservations—Rosebud, Pine Ridge, Cheyenne River and Standing Rock—rank in the lowest 25. Reservations make up all or most of the territory of these four commuting zones.

Among 87 commuting zones in the district, only nine are ranked below the national median of 43.3 for absolute upward mobility (see Chart 1); Seven of them have sizable reservations (at least 600 square miles) and/or tribal populations. The four lowest-ranked commuting zones are almost entirely reservations; the populations of four other commuting zones are between 20 percent and 65 percent tribal. Only one commuting zone below the national median has neither a large reservation nor a large tribal share of population (Sault Ste. Marie in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, which has two small reservations and roughly 4 percent of the population).

There are reservations in many higher-mobility commuting zones, but these reservations tend to be much smaller, and the nonreservation, nontribal population of the zone much larger. There are also a few large reservations in the district located in high-mobility zones. For example, the 1,500-square-mile Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota is split among three high-ranking commuting ones—Bismarck and Dickinson, N.D., and Sidney, Mont. All three are located in or very near the Bakken oil patch, which is generating tremendous economic activity and high-paying jobs.

Tribes on Fort Berthold—Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara, also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes—have also received considerable tax and royalty income from oil production on the reservation, according to state and federal records. In fiscal year 2014, the tribes received $249 million in oil tax revenue; in fiscal year 2013, they took in almost $100 million in royalties, while individual trust land residents earned royalties of at least $350 million (see related article).

"Your identity is rooted in your family, who you are and where you came from." - Eileen Briggs, executive director, Tribal Ventures

Photo by Layne Kennedy

Tough indicators

It’s not difficult to identify some of the likely reasons why upward income mobility lags on many Indian reservations.

The Chetty research team investigated factors associated with either high or low income mobility. Among the variables most correlated with mobility, the nine district commuting zones below the national median scored much lower (or more negatively) in school test scores, size of middle class and fraction of children with single mothers (see Chart 2).

Some of these measures likely carry less explanatory weight than others. For example, commuting zones with large reservations ranked poorly for the size of their middle class. The Chetty team targeted this variable (among others) to see what role income inequality had on mobility. But on reservations, rather than a matter of income inequality (with more high- and low-income households) the absence of a large middle class stems solely from low household income, often 50 percent to 75 percent of the state median. In fact, Chetty’s team measured income inequality more directly (using Gini coefficients, not shown here), and reservation-based commuting zones ranked relatively higher because of the general lack of higher-income households.

Probably no indicator offers more insight to the low-mobility puzzle than education outcomes. The Chetty research, for example, shows that K-12 test scores in district commuting zones below the national median are widely lower than those in other Ninth District commuting zones. Other data from the South Dakota Office of Indian Education offer further clues. For example, the graduation rate for high school students in South Dakota is about 83 percent (measured as a cohort group in ninth grade). Among all South Dakota reservations, the graduation rate is 57 percent. At the Todd County School District, which serves Rosebud, the rate is 48 percent; two Rosebud sources put the rate at closer to 30 percent. In Shannon County, home of the Pine Ridge Reservation, the state says the graduation rate is just 7 percent.

Reservations also struggle with other, related problems. Domestic violence and crime are high on reservations, often generated from alcoholism, drug abuse and depression that are “pandemic,” according to a Simply Smiles, a tribal children’s services program on the Cheyenne River Reservation.

Those struggles trickle down to youth, who often lack communal gathering places and activities, according to several tribal sources. The rate of violent teen deaths in Todd County is roughly four times the state average, according to South Dakota KIDS COUNT. According to congressional testimony by Julie Garreau, executive director of the Cheyenne River Youth Project, native youth nationwide are two to three times more likely than other youths to commit suicide, but tribal youth in the Northern Plains region “are often five to seven times more likely” to take their own lives.

“I think a lot of our young people are really struggling to find their place here,” said Eileen Briggs, executive director of Tribal Ventures, a 10-year-old initiative to reduce poverty on the Cheyenne River Reservation funded by the Northwest Area Foundation. “So if they want to survive, sometimes they will leave, not because they don’t want to live here, but because there isn’t opportunity here for them.”

Poor yardsticks

Given these challenges, it would be easy to assume that tribal members living on the reservation are heading for the exits en masse, looking for a better life off the reservation. But that doesn’t appear to be the case; in fact, there is evidence that the opposite might be occurring—many are staying or seeking to return, which speaks to a reservation dynamic that is not easily captured by income or other socioeconomic data.

Wayne Ducheneaux II, Cheyenne River

Sioux tribal council member

Photo courtesy of Bush Foundation,

Native Nations Rebuilders

Wayne Ducheneaux II is a tribal council member with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, a lifelong resident of the reservation and the son of a two-time tribal chairman and former president of the National Congress of American Indians. He said you can’t judge the quality of life on the reservation from the outside, or from the official data. “While you have the high poverty, the high unemployment, and the material quality of life is very poor, the family, the spiritual, the emotional quality of life is very high here because we’re close-knit. You thought everybody in Mayberry knew everybody’s business. It’s 10 times worse here. Everyone’s related to everybody.”

The matter of population growth—especially from returning tribal members—is difficult to pin down exactly. Census figures suggest modest growth in population. Todd County, which is entirely reservation territory, has grown by 10 percent since 2000, according to U.S. Census estimates.

Then there’s the recurring matter of accurate counts, which tribal officials often dispute. Official statistics say the population of the Cheyenne River Reservation grew by about 300 from 2010 to 2013, or 4 percent. Many believe that significantly undercounts the population increase.

Ducheneaux said tribal members make up about 80 percent of the reservation’s population, or about 6,000 people. But tribal enrollment “is currently hovering right around 20,000 members. There’s no way in hell two-thirds of our population lives off the reservation,” he said. To do so would mean members live outside both Dewey and Ziebach counties, whose boundaries closely mirror those of the reservation—all 4,300 square miles of it, fourth largest in the country.

Based on tribal applications to federal grant and other programs, according to Ducheneaux, the tribe believes the Native population on the reservation is closer to 10,000. “I would argue that it’s more than that,” said Ducheneaux. “It seems to me that on any busy Friday, any payday Friday, you have 6,000 Indians in Eagle Butte that day.”

Confirmation of whether population growth on reservations is large or small, real or imagined, is difficult. But there is evidence that official head counts on reservations are understated. In a 2012 report, the Census estimated that its 2010 survey had undercounted the American Indian population living on reservations by 4.9 percent and overcounted the Indian population living off reservations by 2 percent. Nationwide, the overcount of all people was estimated at just 0.1 percent.

The Cheyenne River Sioux have been working on this population matter with the state demographer, who has presented some preliminary evidence that post office receptacles on a per capita basis are much lower in Indian communities. In turn, this would negatively affect the number of native households receiving (and returning) census questionnaires, potentially leading to an undercount, according to Lakota Mowrer, assistant director at Four Bands Community Fund.

Home is for the heart

The idea of growing reservation populations flies against the challenging winds that life on the reservation can present. The income mobility data from the Chetty project make it clear that reservations are not the place to get ahead financially. Conventional wisdom says to find opportunity elsewhere.

But for Native Americans growing up on reservations, suffice to say that not all decisions are financial ones. Roughly a dozen sources on the Rosebud and Cheyenne River reservations were virtually unanimous in their belief that more tribal members are returning after a spell off the reservation, most often from a spiritual calling or a duty to their tribal family.

According to White Bird, who moved from Denver, “for me, part of it is spiritual. ... The one thing I really like is that capitalism isn’t the religion here. ... You can figure out a way to make it, and people will help you along the way. If you are homeless and your family can’t help you, you can always go to the tribe. I appreciate that culture of generosity,” she said. Of course, not every tribal member acts in such a way, she said, “but the understanding of how we should be is still there. That’s why I live here.”

Cora Mae Haskell has lived her whole life on Cheyenne River and is the asset development coordinator for the Four Bands Community Fund. Before that, she taught for more than a decade at the high school.

“I see many of the students I taught returning to the reservation for various reasons, but mostly because it will always be their home,” said Haskell. She believes more young tribal members are returning home now than in the past, in part, because they were more likely to leave the reservation for advanced education, “and now they feel a need to return to actually help their tribe and their families.” Most still have family on the reservation, and “they feel it is time to come home to be with family, which is a value very close to all Lakota people.”

Haskell herself is a mother of six, four of whom have always lived on the reservation and “one that has returned after 25 years away”—a younger daughter who has lived and worked “at various places, but decided there is no place like home.”

Cora Mae Haskell with family members from four generations, Eagle Butte, S.D.

Photo by Layne Kennedy

Briggs, from Tribal Ventures, grew up on the reservation, her mother a tribal member and her father a nonmember. When she was 12 years old, her family had to leave the reservation when her mother became ill, and “when we left, I thought I would just go away—like, we would come back and visit grandparents and such, but I didn’t expect that I would live here.” There wasn’t much opportunity to begin with, she said, and her mother later died, loosening her ties to home even more.

Or so she thought. Briggs lived in different places—Minneapolis; Madison, Wis.; Columbus, Ohio—but as she grew older, occasional trips back home started taking on new meaning, “like I’m always coming home here,” she said. Eventually, she returned to be with family. “I actually came back for my mother, even though she was passed. It’s all your connections to who you are. Your identity is rooted in your family, who you are and where you come from,” said Briggs.

Many, like Briggs, are giving up better financial opportunities elsewhere to come back and support development in their own communities—something that is surely worthwhile, but doesn’t necessarily compute favorably or immediately on income mobility indexes.

Wizipan Little Elk, director, Rosebud

Economic Development Corp.

Photo courtesy of Native Sun News

Wizipan Little Elk, director of the Rosebud Economic Development Corp. (REDCO), believes the attraction to come home is growing. “I see a lot more people who are in their 20s that are going off, going to school and coming back and working at home. It’s one of the things where we need those people to come home for a quality of life and education. We need our own tribal members here to help develop the tribe, and it’s something I think is becoming more prevalent.”

Little Elk is living what he’s preaching. He grew up on Rosebud, left after graduating from high school and eventually graduated from Yale University. But as a freshman, he said he had an “epiphany” while home for Thanksgiving.

“I’m driving around at two in the morning through St. Francis, and I just look around and I realize that everything is wrong. It just doesn’t fit, it’s not right, the poverty”—a stark contrast to “going to school with some of the richest and most powerful children in the world,” said Little Elk. “So I kind of had this epiphany where whatever I do in life has to have an impact on improving the quality of people’s lives” on Rosebud.

It didn’t happen overnight or as Little Elk had planned. After interning for former U.S. Sen. Tom Daschle doing Indian affairs work, he got a lobbying job in Washington D.C., and later went to law school. In 2008, Little Elk landed on newly elected President Obama’s transition team for his role in drafting a 50-state strategy for garnering Indian election support, and he eventually became deputy chief of staff for the assistant secretary of Indian Affairs.

But all the while, Little Elk’s attention was not far from home. “The plan, my wife and I, our plan was to come back in 2012,” after the president’s first term. But life intervened. Little Elk had already lost a brother in 2007, and his sister died in 2010, leaving behind a 2-year-old son. So Little Elk and his wife moved back. “I was called home. ... My spiritual guides said it’s time for you to come back.”

He returned with no formal job in hand, but did some work for the tribe. Eventually, the REDCO position came open, “and so I put my name in the hat and here I am, a little over two years later.”

Needs list

None of this should imply that everyone who leaves the reservation comes back, or that those who do return find perfect harmony or stay permanently. Sources widely acknowledged that reservation life presents considerable obstacles for growing roots, particularly for the well- educated.

Returning to the reservation invariably involves some economic sacrifice—being underemployed and underpaid (sometimes both) or living in crowded or substandard housing. Any notions of returning home also bring up questions about the quality of schools, job opportunities for spouses and even where families can live—something Little Elk experienced firsthand.

“The hardest thing, when my wife and I moved home, we lived with my mom for four months because we couldn’t find a place to live,” said Little Elk. “So there’s a lot more issues than just people wanting to come back.”

Pay scales also are much lower on the Rosebud Reservation—even in comparison with other reservations with healthier economies. A decade ago, Shawn Bordeaux decided it was time “to come home to work and live to be near family” on the Rosebud Reservation, leaving his post as the vice president of Ho-Chunk, Inc., the economic development arm of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. He accepted a pay cut of more than 50 percent to do so. “I was happy to take a pay cut,” said Bordeaux, who then rephrased. “Or more like, I was happy to find a good-paying job” that helped him come back.

Bordeaux took a job at Sinte Gleska University as a consultant working on economic development, planning and legislative affairs. He is now the director of the Land Institute at Sinte Gleska and directs four federal grant programs. “I haven’t had a pay raise since I started. But I am content, and that is all that counts.”

Little Elk agreed that it can be “extremely difficult to bring people back because we can’t pay them enough. And I don’t think people want to make money hand over fist, but they want to at least feel that they’re fairly compensated.” In one example, Little Elk said, REDCO hired a “kid who came out with his MBA, very smart, very talented, but I ended up losing him because I couldn’t pay him enough.”

But for many, the inconveniences and self-sacrifice of living on the reservation pale to the obligations many feel toward their people. Maybe no one embodies that notion for the Rosebud Sioux Tribe like Lionel Bordeaux, father to Shawn Bordeaux and president of Sinte Gleska.

Lionel Bordeaux, president, Sinte Gleska University, left and son, Shawn Bordeaux, director, Land Institute at Sinte Gleska University

Photo by Layne Kennedy

The senior Bordeaux grew up in White River, about 20 miles north of Mission, “in a rural area, no plumbing, no heat, no what-have-you, walked a mile for a pail of water and you chopped wood. You didn’t have anything to compare it with, so you thought, ‘that’s a good, happy life, a lot of horses and fishing and hunting.’”

After graduating valedictorian of his high school class, Bordeaux left the reservation for college, graduated and worked in different places for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), during which he pursued his doctorate at the University of Minnesota. “I’m 32 years old with a family of four little kids, and my life seemingly ahead of me all laid out.”

As Bordeaux neared the completion of his doctoral degree, a tribal elder, Stanley Red Bird Sr., “called me and then came to my apartment with the damnedest message that I could ever hear at that time,” said Bordeaux. “He said, ‘I’m here to give you a message. I recruited, and I used medicine men and spiritual leaders and their ceremonies to help me find a Lakota-speaking young guy who has academic credentials and ... your name has come through from the spirit world. I’m here to tell you that you’ve been selected to be the next president of Sinte Gleska.”

That was all it took. Bordeaux moved back to Rosebud, assumed his leadership position at Sinte Gleska and took a pay cut from what he had been earning with the BIA. He also received no retirement benefits—the same today—because, as Redbird told him that day, other tribal members “don’t have financial security when they grow old, so you can’t have any. So to this day, I don’t have retirement and I’m going on 42 years here.”

Bordeaux sees firsthand the difficulties parents and their children experience on the reservation. He sees it in his students, many of whom struggle to pay for tuition or even the means to get to class. The school recently developed a transportation system to bring students to school from across the expansive reservation. It also instituted a day care and access to a modest meal for students in need.

“Some of the students get on that bus at seven in the morning and they’re here until [late] at night, and that’s all the food that they have.” Before the bus service was operating, “one guy I used to pick up used to sleep in a culvert. ... He would come to school, and if he wasn’t picked up, he’d sleep in his culvert and then next morning he’d turn around and come back to school again.”

It’s those students, striving for a better life, that give Bordeaux hope. “You always have that hope. Hope’s not a strategy, but it’s sometimes all that you have and everybody ought to be allowed to dream. Dreams started this [university] and it’s now a reality. So, yeah, your hope is always to train as many and get as many young ones to come back and to find their role, and know their responsibility as a teacher to the next generation,” said Bordeaux. “So you always have an evolving dream that’s materializing generation to generation.”

—Claire Hou, research assistant, contributed data and other research to this article.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.