The rollout of the Affordable Care Act has been one of the biggest and most-watched policy developments in years. While various employer-based mandates have been postponed (in some cases, several times), implementation of the law for individual health insurance was completed in the spring. While Ninth District states took different approaches to sign-ups, they had comparatively strong enrollment. But there was considerable variance in the populations eligible for and ultimately getting insurance and in how much they had to pay.

Marketplace structure: In this first round of implementation, only individuals were required to sign up for insurance coverage by March 31 or face penalties of $95 a year or 1 percent of their annual income, whichever was higher. Health care exchanges created a “no wrong door” approach that allowed individuals to apply, depending on their household income, for health coverage either through marketplace plans offered by insurers or through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP); the latter two programs are publicly financed health care for poor adults and children.

States were given the choice of constructing their own exchange for health insurance plans or using the federal exchange (healthcare.gov). The majority of states (34) chose the federal option, including Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin. Sixteen states (including Minnesota) plus the District of Columbia constructed and operated their own health insurance exchanges.

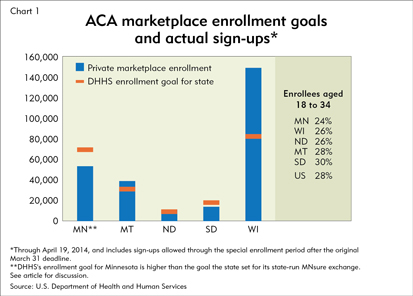

Private insurance enrollments: In the fall of 2013, enrollment goals were established for all states by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), based in part on a state’s population and the percentage of residents that were uninsured. For example, Montana’s ACA enrollment target as a percentage of total population (3 percent) was more than twice the rate of Minnesota’s (1.2 percent) because the uninsured make up 17.5 percent of the population in Montana compared with Minnesota’s rate of 8.5 percent.

Private-insurance enrollments nationwide and in Ninth District states were slow-moving at first. By the end of February, overall sign-ups as a percentage of the nationwide enrollment goal were still at 60 percent; among district states, they ranged from a high of 90 percent in Wisconsin to a low of 36 percent in South Dakota.

As the deadline loomed, March enrollments poured in, growing by 81 percent across district states; enrollments in the Dakotas and Wisconsin all grew by more than 94 percent. As a result, Montana, North Dakota and Wisconsin met their enrollment goals or came very close, while South Dakota and Minnesota missed (69 percent and 75 percent of goal, respectively; see Chart 1).

(The DHHS goal for Minnesota was much higher than the state’s own goal for its state-operated MNsure exchange. MNsure’s board of directors set an enrollment goal of about 40,000 shortly after the website went live in October following significant technical difficulties. The board later revised that goal to about 50,000 in December, which has been exceeded.)

The age distribution of enrollees skewed higher than originally projected. For health insurance markets to work efficiently, the number of younger (and healthier, actuarially speaking) enrollees has to balance out the number of older, less healthy enrollees. It was originally estimated that 18-to-34-year-olds would make up 35 percent to 40 percent of all enrollees. By the end of the sign-up period, that enrollment was just 28 percent nationally, though it improved from 25 percent at the end of February. Among district states, the number of young enrollees varied between 24 percent (Minnesota) and 30 percent (South Dakota). Wisconsin jumped from 21 percent to 26 percent over the last month of sign-ups.

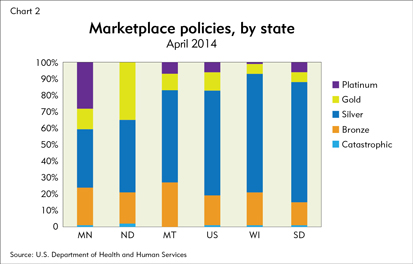

Plan preferences, costs and subsidies: Private marketplace insurance plans use metal categories—bronze, silver, gold and platinum—to designate insurance coverage and out-of-pocket costs. Bronze is the lowest-cost plan; 60 percent of costs are covered by insurance, and 40 percent are borne by the consumer. Each succeeding plan level increases cost coverage by 10 percentage points (to 90 percent for platinum). “Catastrophic” plans with lower premiums than bronze plans are also available, but have typically attracted just 1 percent of enrollees.

Silver plans have been the most popular choice for subscribers, both nationwide and in the Ninth District (see Chart 2). But consumer preferences diverge markedly among district states. For example, North Dakota enrollees have chosen gold plans almost as often as silver, and Minnesota residents have had one of the highest rates of platinum sign-ups in the country, at 27 percent—significantly higher than the 5 percent rate projected by the state, and more than four times the national rate (6 percent).

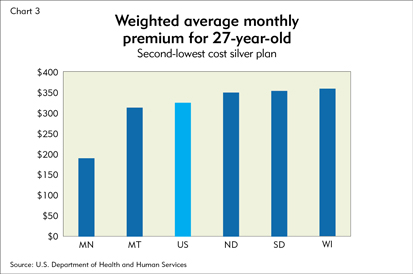

Some of this variation appears to be tied to average premiums. For example, Minnesota enjoys some of the lowest-cost plans in the country (see Chart 3). The premium range between low- and higher-cost plans is also less in Minnesota than in many other states. As a result, Minnesota buyers appear to be trading up fairly often to higher platinum coverage for only moderately higher premiums.

There are drastic price differences even among nearby regions. For example, consumers in the Twin Cities pay among the lowest monthly premiums in the country, in part because insurers can choose from four major health care systems, some of which “have been in the vanguard of experimenting with more efficient ways to care for patients,” according to Kaiser Health News.

Meanwhile, premiums just across the Wisconsin border (in Pierce, Polk and St. Croix counties) are more than double because of different insurers, doctors and hospitals. But rates immediately to the north in Wisconsin are considerably cheaper.

(Coverage cost comparisons are tricky because plan costs depend on plan choice as well as household characteristics such as age, income and number of children. This means there are literally hundreds of potential cost comparisons. But geographic cost differentials are generally consistent when plan variables change.)

What’s not clear is why low premiums in Minnesota have not yet translated into heavier insurance purchasing in Minnesota. For example, the DHHS projected only slightly higher private enrollments in Wisconsin (79,000) than in Minnesota (67,000). Yet Wisconsin’s enrollment by the April deadline was nearly three times that of its western neighbor. Aside from early technical problems with MNsure’s website, another possible reason may be higher deductibles. There is very little comprehensive information on this cost factor, but a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report found that Minnesota plans had the highest average integrated deductibles among 10 states surveyed, at about $4,000.

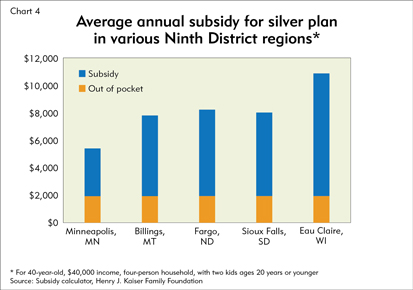

The ACA provides significant subsidies for marketplace buyers at different levels of income above 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Those at 138 percent and below are eligible for public health insurance. More than 80 percent of private insurance enrollees received some financial assistance. These subsidies apply evenly to all buyers based on their income, family size and plan choice, essentially capping out-of-pocket expenses.

The subsidy is significant for a household earning just over 138 percent of FPL and gradually falls as income rises (and more gradually for families with children). Because the subsidies cap out-of-pocket costs, low-income consumers in Minnesota receive smaller average subsidies than those elsewhere whose overall plan costs are higher (see Chart 4).

Medicaid expansion: One of the key pieces of the ACA—and its goal to cover more uninsured people—was the expansion of Medicaid, a federal-state health insurance program for the poor.

As originally enacted in the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was to be expanded to nearly all adults with incomes below 139 percent of FPL (about $32,500 for a family of four in 2013). This expansion was to be administered by states, but financed by the federal government at 100 percent for the first three years, with states assuming a 10 percent cost share thereafter.

However, in June 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the required expansion of state Medicaid was unconstitutional and allowed states to expand at their own discretion. A total of 26 states and the District of Columbia have chosen to implement the expansion, including Michigan, Minnesota and North Dakota among district states, according to the Advisory Board.

A significant pool of the previously uninsured population in these expansion states now has access to public insurance coverage—for example, 41 percent in Minnesota and 32 percent in North Dakota, up from about 6 percent to 8 percent pre-ACA in both states. That translates to around 130,000 newly eligible adults in Minnesota and 24,000 in North Dakota, according to estimates by the Urban Institute.

At the same time, 24 states so far have opted out of the Medicaid expansion—including Montana, South Dakota and Wisconsin—most of them under Republican leadership and citing general opposition to the ACA and the belief that state costs would rise beyond federal estimates and outstrip assistance over the long run.

The Supreme Court ruling means that many low-income, uninsured adults in states that did not expand Medicaid will likely not obtain any health coverage, or will do so at high cost. This is because of the so-called coverage gap—they earn too much money to be eligible for Medicaid in their home state, but not enough to qualify for subsidized marketplace health insurance (starting at 139 percent of FPL; these subsidy levels were not revisited by Congress after the Supreme Court’s decision).

Nationwide, about 7.6 million poor, uninsured adults would have been newly eligible for Medicaid had all states expanded coverage, according to an April estimate by Kaiser. That includes more than 100,000 in Montana and South Dakota (combined), where childless adults are not covered at all, and Medicaid income eligibility is much tougher for a parent with two children, at roughly 50 percent of FPL in both states.

By opting out of Medicaid expansion, Montana, South Dakota and Wisconsin are dealing with various coverage scenarios for adults (thanks to different Medicaid eligibility guidelines) and related political debates. In Montana, Gov. Steve Bullock has discussed holding a special legislative session on Medicaid expansion. Advocates for Medicaid expansion in the state attempted but failed to get the necessary signatures to put a referendum on the November ballot.

In South Dakota, Gov. Dennis Daugaard has sought a waiver from ACA regulations to expand Medicaid eligibility there to 100 percent of FPL, which would have extended coverage to an estimated 26,000. This appears unlikely to be approved by the DHHS, in part because it would still leave a gap of individuals uncovered between 100 percent and 138 percent of FPL, where marketplace subsidies kick in.

Wisconsin, for its part, took something of a middle road between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion. The state actually toughened its eligibility for BadgerCare (the state’s Medicaid program), cutting 77,000 people from the program. But these were adults earning up to 200 percent of FPL, and the state cut these people from the program knowing that they would be eligible for federal marketplace subsidies. The state is also using these BadgerCare savings to extend coverage to all adults (including childless) up to 100 percent of FPL. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Wisconsin is the only state that did not expand Medicaid that will have no coverage gaps among adults earning less than 100 percent of FPL. But the state does have a secondary, ACA-induced coverage gap—53,000 adults—among those with earnings between 100 percent and 138 percent of FPL.

Uninsured: According to the Kaiser Foundation, “a key measure of success of the ACA is whether the number of uninsured Americans drops. While that outcome seems like a relatively straightforward metric, it will in fact be surprisingly difficult to evaluate.” While eligibility for affordable insurance has risen significantly from expanded Medicaid coverage and low-income subsidies for private policies, exchanges have not tracked actual sign-ups by the uninsured.

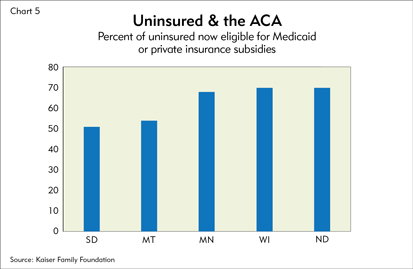

About 70 percent of the nonelderly uninsured in Minnesota, North Dakota and Wisconsin are now eligible for Medicaid or subsidized private coverage, according to Kaiser (see Chart 5); in South Dakota and Montana, it’s about 50 percent, mostly because those states didn’t expand Medicaid eligibility. Among the uninsured that are ineligible for assistance, many simply earn too much money to qualify for either private subsidies or Medicaid coverage.

According to a May report from the DHHS, by the April deadline, Minnesota’s Medicaid enrollment had grown by roughly 100,000 (about 11 percent) over its pre-ACA Medicaid population (July to September 2013 average). But, again, estimates vary. A June report by the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) at the University of Minnesota suggests that public health coverage for the poor grew by more than 155,000 from the end of September to May 1.

In either case, it’s not known to what degree the net increase is the result of newly eligible people enrolling versus people previously eligible (but not enrolled) who decided to do so during the ACA sign-up period.

Among those signing up for private plans, even less is known about whether they were previously uninsured. Health care exchanges have not tracked the previous status of enrollees, though a few outside surveys have made estimates. For example, a mid-March Rand survey found that about one-third of new marketplace enrollees were previously uninsured, which is higher than levels found in earlier McKinsey surveys (27 percent of February enrollees and 11 percent of January enrollees).

Overall, while more uninsured adults are obtaining health coverage through either private plans or Medicaid, there is still a large population of uninsured. An April study by the Congressional Budget Office projected that the new law would reduce the number of uninsured by 12 million this year—roughly split between new private and Medicaid enrollees—or about 29 percent of the nation’s 42 million uninsured (which does not include illegal immigrants). SHADAC’s June report estimated a 41 percent decrease in Minnesota’s uninsured population, driven mostly by sign-ups for public health coverage (which SHADAC pegged higher than DHHS estimates).

For the time being, said a Kaiser report, “A complete understanding of the first year of full ACA implementation will require triangulating across many data sources.” It added that a more complete picture of coverage under the ACA will start to emerge in June 2015, when various federal agencies are scheduled to report more comprehensively on the matter.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.