Economic well-being has always been relative. How well a person or group of people fares rests in part on the fortunes of others.

Not that long ago, North Dakota was one of the have-nots among a nation of haves. The state was losing population, and average earnings were declining compared to the national average. As has been widely publicized, that’s no longer the case. But while most observers attribute the state’s growth to the recent oil boom there, the longer-term story is much more interesting and compelling.

North Dakota’s rise is not unique. Research on historical earnings in three Ninth District states—the Dakotas and Montana—from 1965 to 2011 shows just how far states in the western portion of the Ninth District have come in terms of average earnings. The data also reveal similarities and differences in the performance of these states over time.

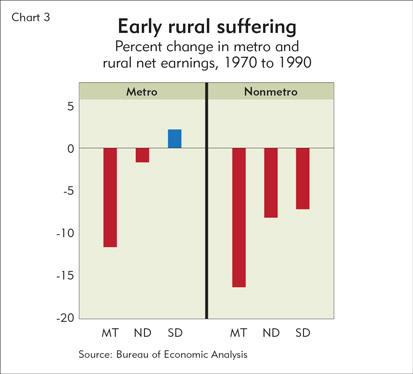

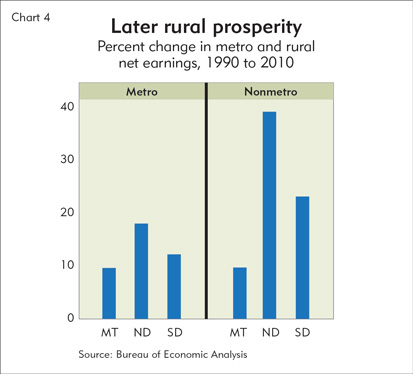

From 1970 to the late 1980s, western district states experienced a hardscrabble decline—mostly due to a struggling farm sector—that saw average earnings drop considerably compared to the national average. But the second period, from about 1990 to 2011, has witnessed an economic rebirth, especially in the Dakotas, with earnings climbing steadily and, in the case of North Dakota, streaking past the national average.

Ultimately, this is a story of economic transition brought about by changes in the performance of certain industry sectors that strongly influence the economies of thinly populated states like North and South Dakota and Montana.

Certainly some of this story is about oil, particularly in North Dakota, which is experiencing an energy boom that requires all such previously labeled periods to bear an asterisk. But earnings growth was plainly visible well before the boom, a matter that is particularly obvious in South Dakota, which has virtually no oil production to speak of. The good news is that the Dakota economies appear to still be on the ascent, and economists in those states see solid fundamentals for continued growth.

Tracking net earnings

To home in on the economic performance of the Dakotas and Montana, the fedgazette gathered data on average net earnings per person from 1965 to 2011 for the Dakotas and Montana. Net earnings, roughly speaking, equal wages, salaries and proprietor income after subtracting contributions to government social insurance programs. These earnings were compared to nationwide earnings over the same period, producing a relative earnings measure for each state over time.

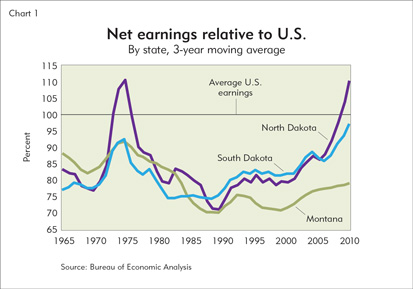

The ratio of state to national net earnings per person often fluctuates modestly in any given year. In 1970, earnings in each of these three states were roughly 75 percent to 85 percent of the national average (see Chart 1). Over the next four decades, these states (especially North Dakota) went through an extremely volatile period, cut into two roughly equal halves of a rags-to-reasonable-riches story.

“These findings fit the North Dakota experience to a T from my perspective,” said David Flynn, director of the state’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research and an economics professor at the University of North Dakota (UND).

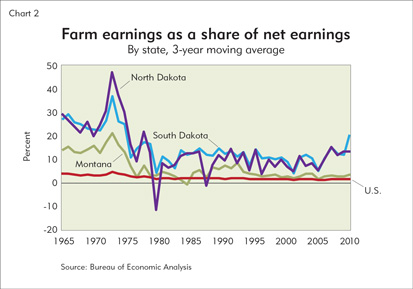

Things started positively enough for the three western district states. Crop and livestock prices rose dramatically in the early 1970s in conjunction with rising exports. Strong farm earnings spilled over into farmland prices and other areas of the economy, increasing nonfarm earnings. With small economies (especially at the time), the effect in these states was direct and large (see Chart 2). North Dakota briefly experienced earnings that were well above the national average.

Ultimately, that growth proved unsustainable; farm prices eroded quickly, pulling the rug out from under farmland values and dealing a harsh blow to these state economies. It’s interesting to note that an oil boom in North Dakota and Montana (to a lesser degree) in the late 1970s and early 1980s had little effect on the economic trajectory in these two states, save for a short blip in North Dakota. By the late 1980s, average earnings in these three district states had fallen to about 70 percent to 75 percent of the national average.

Because much of the earnings drop stemmed from farming, that also meant that rural workers and households took a bigger hit than those in metro areas, though Montana saw a significant drop among earners in both categories (see Chart 3).

Movin’ on up

What happened over the following two-plus decades hardly could have been predicted. Since about 1990, there has been a remarkable resurgence in the western Ninth District economies (see Chart 1). By 2011, North Dakota had caught up to and streaked past the national earnings average, while South Dakota had earned parity—this from a flat-footed 74 percent in 1989.

Economies are complex entities, so the sources of these gains are multifaceted and vary by state. For example, earnings from agriculture and mining (which include oil and gas production) contributed moderately to the relative rise in earnings, but their effects are concentrated in recent years and unequally distributed among these three states (see Charts 2 and 5).

North Dakota has been a big beneficiary of strong farm and energy sectors. Oil production has led to a gusher of economic activity; with a robust farm sector in recent years factored in, average earnings in the state have leaped over the national average. According to Flynn, “There are clearly spillover effects from these sectors into others such as transportation and retail. We have also seen increased demand for services such as financial services and accounting services.”

Montana has likely benefited from growth in both sectors, but to a much smaller extent, while South Dakota has seen little impact from the oil boom; whereas, its farm sector has prospered. Gains in farming and mining—sectors largely conducted in the countryside—also translated to strong earnings gains in rural areas, particularly in the Dakotas (see Chart 4).

But even before fracking for oil and gas became a household word, and before robust increases in farm prices, earnings in the Dakotas were making strides against the national average. South Dakota is an interesting case, because its economy has virtually no presence in oil or other mineral mining, yet earnings there have risen dramatically since 1990.

Some of the growth in relative earnings can be attributed to the fact that South Dakota as well as North Dakota avoided the catastrophic effects of the last three recessions—and particularly the most recent one—seen in other parts of the country. The state’s economic performance looks better on paper simply because it “suffered a less severe recession than did the U.S. ... We did not overbuild and participate in the subprime mortgage fiasco to the same extent as the U.S. did,” said Ralph Brown, an economics professor at the University of South Dakota (USD) and a member of the Governor’s Council of Economic Advisors. The state’s peak-to-trough employment loss was 3 percent—less than half of the U.S. rate of job loss, according to federal labor data.

Brown added that South Dakota has benefited from two major industry expansions. The state has a fairly small manufacturing base, but the sector has witnessed significant growth. The rise of computer-maker Gateway in the early 1990s kick-started sharp growth in employment and income. Across the state, manufacturing jobs grew by 10,000 during the 1990s—an increase of about 30 percent—to over 44,000 jobs.

In 2001, on the heels of a recession, Gateway moved most of its operations from North Sioux City to California, and by 2003 the state had lost about 7,500 manufacturing jobs. A subsequent recovery, followed by the Great Recession and another recovery, has pushed manufacturing employment once again over 40,000, according to Brown.

South Dakota has also benefited from “great growth” in the financial services industry, Brown said, fueled by expansion in credit-card banking. From 1990 to its peak in 2008, Brown said industry employment increased from 17,000 to 31,000—an average annual growth rate of 3.4 percent.

The last recession hurt employment in the financial sector, but some of that slack has been taken up by well-timed growth in the farm sector. From 1990 to 2012, farm income accounted for about 7.4 percent of personal income in South Dakota, Brown noted. But since 2011, farming’s income share has risen to over 12 percent. In 2011, farm income averaged $174,000 per farm proprietor.

Earnings capture only part of the farm impact. Farm production expenses amount to 20 percent of personal income, Brown said, “which makes farming a big player in the economy. Farming itself does not create new jobs directly, but the spending by farmers does. When things are going well, farmers purchase more trucks, tractors, farm equipment, farm building [and so on]. When things are not going well, they postpone these expenditures where possible.”

Flynn, from UND, also pointed out that even when farming wasn’t particularly profitable in the mid-to-late 1990s, the sector was still contributing to stronger households and businesses because “land prices continued to appreciate, so asset values for farmers continued to rise.”

Montana lags its neighbors

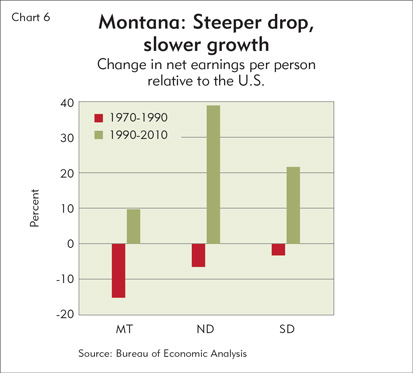

Among the three western district states, Montana has fared the worst, experiencing both a larger fall from 1970 to 1990 and a smaller rise since 1990 compared with the Dakotas (see Chart 6). Montana saw only modest gains in relative earnings, rising from a low of 69 percent of the national average to 79 percent in 2011.

Along with farm struggles shared with the Dakotas in the 1970s and 1980s, Montana also saw two major industries—mining and forestry—go through significant upheaval during this period. The city of Butte was home to the Anaconda Copper Mining Co., one of the largest companies in the world in the 1920s and one of the largest in Montana for its entire operational life. The company went through regular boom and bust cycles, but by the 1970s the mine once known as the “richest hill on earth” was at the end of its useful life. The mine was sold to ARCO in 1977, which shuttered it in 1983.

“We lost almost 8,000 well-paid union jobs at the mines and two refineries” that were shut down with the mine, said Paul Polzin, director emeritus at the Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana who has studied the state economy for 35 years.

In the mid to late 1980s, the wood products industry also mechanized and restructured, resulting in the loss of thousands of high-paying jobs. Employment peaked in 1979 at about 13,500 and has zigzagged its way to roughly half of that level today—the victim of Canadian softwood and other lumber imports, low prices, slow housing markets and other factors. Montana’s forest products industry made up about 16 percent of the state’s economic base in the late 1980s, according to Forest Service research. That share has steadily dwindled. By 2006—a year before the start of the home-building collapse and recession—it had fallen to 9 percent.

All Montana’s relative earnings growth has come since 2000—and most of it occurred before 2007 as mining and construction industries fed off the housing boom and rising commodity prices. Though the state did not suffer as steep a downturn in the subsequent recession as the nation, the housing collapse nonetheless knocked the state’s growth trajectory lower starting in 2007.

Seizing opportunity

Economic fortunes have swung so dramatically in the Dakotas that it’s easy to forget the arduous economic path both states were treading in the 1980s—well, it’s easy for non-Dakota residents to forget.

Brown, for one, said, “I think South Dakotans appreciate the significant changes that have taken place in the state over the decades.” Some change requires time to take hold. He pointed to the development of a four-year medical school at USD in the mid-1970s “that led to many more South Dakota physicians and the subsequent development of Sioux Falls as a regional medical center.” Combined with the city’s financial services niche and an expanding economy in general, “college-educated students, more than ever before, do not have to move to the Twin Cities, Omaha or Denver to find a job compatible with their education,” Brown said.

The state is also well positioned to benefit from worldwide demand for food, fiber and energy, Brown said. The state’s business climate is an attractive selling point to businesses of all types, and while “growth of the financial sector is a bit more murky ... demographics and public policy will drive the demand for medical care, which will continue to be a growth sector in the economy,” said Brown. “I think South Dakota is poised to take advantage of whatever that future may hold.”

In North Dakota, the oil boom offers the state a unique opportunity to mold its future for generations. Almost fortuitously in retrospect, the state has seen prior booms and subsequent busts that left painful scars. Now many firms, investors and other market participants are battle tested.

As the economic promise becomes more tangible with every new oil well, Brown added, “I think there are more that view this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. ... Individuals tend to recall the oil bust of the early 1980s and use that as an argument for better planning. As a result, I think the gains are likely more permanent in nature.” The boom has sparked discussion across North Dakota about “the structure of the tax system, about infrastructure needs and economic development. I interpret these as efforts to capitalize as much as possible on the current growth environment and lock in whatever gains they can.”

Map: County-level change in earnings

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.