Market swings create winners and losers. So it is in rental markets, where property owners appear to finally have some breathing room with profit margins, while renters are starting to feel a little squeezed.

It’s almost to the point of suffocation for low-income renters. There are virtually no vacancies in this market segment to begin with, and when demand increases—from job loss, home foreclosure and the like—many low-income renters have to scramble for shelter.

“Certainly, we know homeless counts are going up. And we know that families are doubling up in apartments. All of the shelter system is at capacity. And people are also having two or three jobs to help cover rent” at more expensive units, said Sue Speakman-Gomez, president of HousingLink, an affordable housing clearinghouse in the Twin Cities. People of very low means are having more difficulty obtaining an affordable unit, she added, but so are those who have “any other barrier in their history,” such as being unemployed or having a prior eviction or criminal conviction on their record. For these would-be renters, “it’s significantly harder to find a place,” she said.

Patrick Dienger is the executive director for the La Crosse County (Wis.) Housing Authority and has been involved in public housing for 22 years. Over that time, “I’ve seen things fluctuate,” he said. “But I see this as a particularly desperate time.”

Dienger said that “the calls to my office have increased” with the rise in foreclosures. Smaller households are moving in with mom and dad, or maybe with their kids. “Or they move from friend to friend until the landlord gives notice” when occupancy limits are exceeded. Other options include the YWCA, the Salvation Army and a local warming shelter, though the latter is not designed for overnight stays, and users have to sleep sitting up. “There’re also campers in the summertime, and park benches.”

While the past decade provided relative stability for many renters in terms of costs (see cover article), people and families of modest means faced challenges even before the recession. Rampant job loss, flat wages and a surge in home foreclosures since the recession have put even more pressure on renters in a market with few vacancies, compounded by the fact that construction of new units for low-income households hasn’t kept up with demand.

As a result, more renters are paying a high percentage of their income toward monthly rent, and public rental assistance programs are ill-equipped to help much. Vacancy rates in these programs, already very low, have gone to virtually zero, and waiting lists for housing assistance have lengthened to the point of system paralysis.

Wanted: Cheap digs

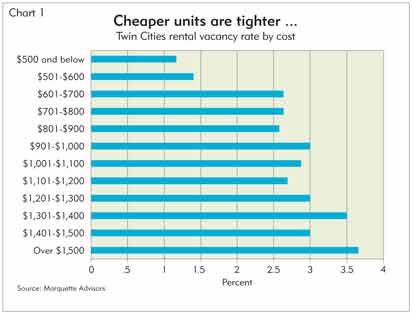

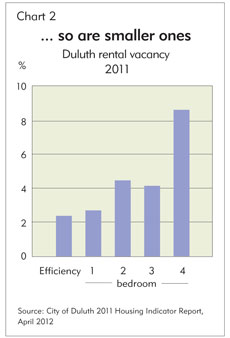

Though rental vacancies are tightening across the district, not all rental segments are created equal. Smaller and less-expensive units are particularly scarce as more households look to stay within tight budgets (for examples in the Twin Cities and Duluth, Minn., see Charts 1 and 2).

Low-cost housing, “from what we’ve heard, is the tightest market. But it always is. There will never be enough of that,” said Mark Obrinsky, chief economist for the National Multi Housing Council.

Speakman-Gomez noted that demand for low-cost housing units, especially units targeted to the very lowest income groups, “has been very high for the past decade. In my 10 years at HousingLink, there has never been a time where we have routinely seen openings in very affordable units being advertised.”

Part of the problem, along with joblessness and stagnant wage growth at the low end, is that new construction of low-income housing “is not keeping pace with demand,” said Speakman-Gomez. She said thanks to creative efforts to utilize available tax credits, “we do see some production. But not enough.”

Arguably, in an unconstrained market, some private developers would build units of a size and type affordable even to those of modest means. That they can’t or won’t is the result of myriad factors, including high land and construction costs and a panoply of local and state regulations that affect everything from minimum unit size to safety issues to parking requirements. All of this adds costs and strings out the development process. Neighborhood opposition also plays a role, particularly for smaller, no-frill units that would be affordable to low-income renters without subsidy. These and other factors increase costs and reduce (even negate) profits, pushing many private housing developers to seek better profits building units suitable for higher-income tenants.

In turn, government has become very involved in low-income housing, including the development of new units, most of which are built with the help of the federal Low Income Tax Credit, which goes to qualified investors building low-income housing. But even this activity slowed with the recession. In 2008, for example, about 3,100 low-income rental units were built in district states using the LITC—the lowest number since 2000, and about 20 percent lower than in 2006, according to program records.

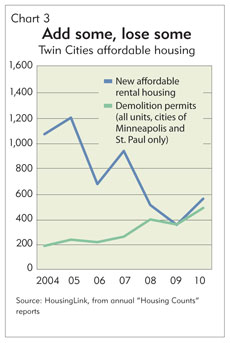

At a regional level, data from HousingLink show a considerable drop-off in new low-cost units in the Twin Cities since the recession, though the decline is smaller in percentage terms than the decline in market-rate units over the same period. Compounding the supply problem is the fact that demolitions have increased in some markets where demand for affordable units is particularly high, and these units tend to be older and in poorer condition (and thus more affordable). In 2009 and 2010, there were almost as many demolitions in Minneapolis and St. Paul as there were new affordable units in the 50-plus communities of the Twin Cities metro area (see Chart 3).

Tight housing and economic conditions—and recently, escalating rents—have pushed more households to seek public assistance. The problem is that there is little excess capacity in public housing assistance programs to help those in need. There are a variety of rental assistance programs, but the two big ones are publicly owned housing, where rents are subsidized by federal and state funding based on household income, and Section 8 vouchers that act as cash to buy down rents at qualified units.

A check of programs in several cities shows that vacancy rates are well below those of market-rate units. The St. Paul Public Housing Agency, for example, owns or manages more than 4,200 rental units. At the end of February, eight units were available, a vacancy rate of 0.2 percent; only 44 units came open at any point during the entire month. That’s worse than in previous years, but only slightly. In 2002, average vacancy was 42 units (1 percent). It has slowly dwindled every year since, to 13 units (0.3 percent) in 2011 and fewer than 10 units for the past seven months.

The Section 8 program in St. Paul is just as tight. In fiscal year 2011, no new families on the regular waiting list were issued vouchers and “leased up,” according to the program’s annual report. Only a fortunate few in programs for veterans, the disabled and other special groups were placed.

Even those lucky enough to receive a new Section 8 voucher aren’t guaranteed a place to live, because “it can be hard to find an owner willing to accept the voucher and wait the two weeks that the inspection and paperwork take to get the renters into the unit,” said Speakman-Gomez. “Instead, owners are opting for renters without assistance who can move in immediately and pay rent right away.”

That hasn’t stopped more people from seeking help, and waiting lists have exploded. St. Paul Public Housing has 7,700 applicants on its waiting list; the Section 8 waiting list has almost 3,900 names and has been closed since 2007 due to lack of turnover—mere dozens in the past two years. In fact, around the Twin Cities, Section 8 waiting lists at six of seven county-level housing authorities were closed to new applications, and Scott County was accepting applicants only for three-bedroom units, according to an October 2011 report by HousingLink.

It’s the same story elsewhere. In Sioux Falls, S.D., almost 1,800 people are on housing assistance. But there are more than 3,000 families on an estimated four-year waiting list, according to the Sioux Falls Housing and Redevelopment Commission. In Duluth, Minn., public housing vacancy fell from 3.6 percent in 2007 to 1 percent last year, and the waiting list increased by about one-third to almost 1,000, according to a city housing study. The waiting list for Section 8 vouchers increased from 1,400 to 1,800 over the same period, and the city estimated wait times at 12 to 24 months.

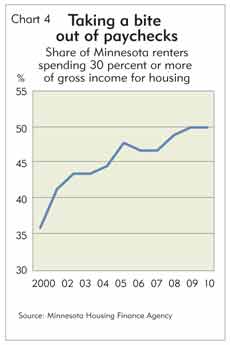

As a result, more renters of modest means are finding themselves in market-rate units, and many are spending more than 30 percent of their monthly gross income on rent—a rough, but widely accepted threshold for affordability. A 2011 housing affordability report by the city of Sioux Falls found that 45 percent of renters were spending above this benchmark. In Bozeman, Mont., despite a decline in home prices and rents in recent years, renters paying over 30 percent of their income for rent increased markedly over the past decade, reaching 49 percent, according to an April city housing plan. The entire state of Minnesota experienced a similar increase, according to figures from the Minnesota Housing Finance Agency (see Chart 4).

Scarce resources

Little change is expected in the short term, mostly because demand swamps supply by such a large margin. Tight fiscal conditions at every level of government don’t help much, though housing assistance funding in some places has been on the uptick. In Minnesota, housing assistance channeled through about 40 different programs large and small increased from $514 million in 2009 to $727 million last year, according to the Minnesota Housing Finance Agency (see Chart 5).

Despite the funding increase, however, the number of households served dropped by 6,000 (about 10 percent) over this period, due in part to large spending increases in home-purchase, rental-construction and rental-rehabilitation programs, which are proportionately more expensive per unit served compared with direct renter assistance like Section 8 vouchers.

More affordable housing units are expected to be built this year, maybe 600, according to the Minnesota Housing Finance Agency. But with waiting lists across the Twin Cities solidly into five digits, that’s a housing ripple that won’t carry far.

The slow pace of new units is one reason some organizations are helping owners upgrade and preserve units while keeping them eligible for the subsidies that come with low-income renters. Speakman-Gomez said it costs 40 percent less to preserve a unit for a low-income renter than to build a new unit for the same renter.

Other supply shocks might be on the horizon as well, in the form of so-called opt-outs—units that no longer want to serve the subsidized market and convert to market rate. Minnesota has 53,000 private rental units under contract to participate in various renter assistance programs, according to HousingLink. Those contracts expire on a rolling basis between now and 2040, but between 2011 and 2015, three of every eight units (37 percent) will be free to opt out of assistance programs and convert to market rate.

If history offers any insight, however, most will renew their contracts with public programs. Minnesota Housing administers project-based Section 8 contracts for more than 30,000 assisted units and thousands more for which it provides asset management oversight and/or supportive services under various income-based public housing programs. While just a small portion of contracts expire every year and have the chance to exit, as of mid-May, contracts for fewer than 100 project-based Section 8 units have not been renewed since 2010, according to Minnesota Housing.

Cam Oyen, housing program specialist from Minnesota Housing, said there “is sort of a little bubble last year and this” for expiring contracts. “But the vast majority renew. We’ve not seen a huge increase in the number opting out.” There are several reasons. In many cases, continued program involvement might have been a prerequisite for getting financing in the first place, Oyen said. Many nonprofit property owners often have social missions and “are very motivated to stay in the program.”

But Oyen acknowledged that current conditions in the rental sector make for “a lot of unknowns” regarding opt-outs. “Rental markets are better now, and that may be something people are watching.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.