Health insurance serves as armor against the sticks and stones of life. Given the high—and rising—cost of health care, it’s difficult to overstate the importance of financial protection against illness or injury. But all aspects of that protection—who provides it, how much it costs, what it covers and who’s left uncovered—are in flux as various players in health care and insurance markets jockey for position.

For example, regardless of where you live, you and your family probably have health insurance coverage provided by an employer. But the proportion of those wearing employer-issued armor has been dropping, and employers that continue to offer coverage are making some fundamental design changes. An increasing proportion of working-age people—primarily low-income earners and the unemployed—receive health coverage from public sources. For them, health coverage depends to a surprising degree on which state they call home.

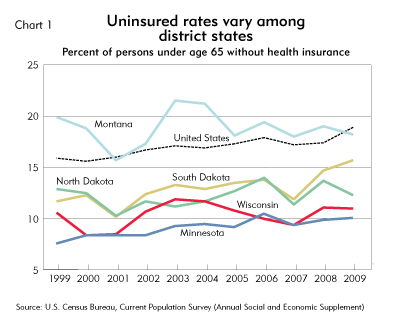

Health insurance coverage is more pervasive in the Ninth District than in many other parts of the country. In 2009, the rate of uninsured children and working-age adults was lower than the national average in every district state, according to U.S. Census figures (see Chart 1). Rates among district states vary considerably. Montana only recently dipped below the national average, and just barely, while rates in Minnesota and Wisconsin are significantly lower.

These differences stem from a number of factors, including the mix of industries and the relative share of large versus small businesses (large employers are more likely to offer workplace coverage) in each state. Public policy also has a strong bearing on uninsured rates in the district; some state governments have gone further than others to provide coverage to low-income people.

Uninsured rankings within the district—lower rates in eastern states, higher rates to the west—haven’t changed much over the past decade. And for the most part, district states have bucked the national trend of slowly declining coverage; in 2009, the uninsured rate in each state was about the same as it was 10 years earlier. Only South Dakota’s rate was markedly higher.

But this picture of consistency—disturbed only by increases in uninsured rates during recessions—obscures the changing dynamics of health coverage in the district and nationwide.

Employer-sponsored insurance is less extensive than it was a decade ago. Nationally and in most district states, the proportion of people covered by workers’ policies has fallen, despite cost-cutting efforts by employers, such as requiring employees to pay more out of pocket for health care. The Great Recession further undercut coverage by forcing employers to lay off workers or curtail health care benefits.

Higher enrollment in public insurance programs during the economic downturn dampened the impact of these losses. Some district states have gone to greater lengths than others to provide low-income people with an alternative to private coverage. Minnesota, for example, sponsors a public insurance program subsidized by a tax on health care providers and in January expanded its Medicaid program to cover single adults.

However, such programs run the risk of “crowding out” private insurance—inducing firms and workers to switch to taxpayer-subsidized coverage. Thus public insurance can reduce participation in employer-sponsored insurance. And funding of expensive public insurance programs may be unsustainable in district states facing budget deficits in the wake of the recession.

Federal health care reform—not a sure bet because of repeal efforts in Congress and legal challenges—is expected to expand health insurance coverage nationwide within a few years. In the district, “Obamacare” would have the biggest effect in states such as South Dakota that have relatively high rates of uninsured.

Ailing workplace coverage

For many workers, jobs offering health care benefits are a powerful draw. For family coverage, employers typically pay at least two-thirds of the insurance premium—a boon for any household trying to make ends meet (although the trade-off is lower wages). But not every worker has access to employer-sponsored insurance, and workplace coverage varies widely among district states. In 2009, the share of nonelderly people covered through the workplace—including spouses and dependents of workers—ranged from about 70 percent in Wisconsin to 54 percent in Montana (see Chart 2).

This variation stems from the different commercial makeup of each state—the proportion of large versus small businesses and the distribution of employment by industry. Minnesota and Wisconsin have health coverage rates well above the national average because a large proportion of workers in those states are employed by types of firms that are more likely to offer coverage—large concerns and those in the manufacturing and service sectors.

In Wisconsin, for example, firms with more than 50 employees accounted for 70 percent of the workforce in 2009, according to data compiled by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). And only 6 percent of workers were employed in agriculture, forestry, fisheries and construction—industries with lower rates of employer insurance. In contrast, Montana has sparse workplace coverage because it has the highest share of workers in firms with fewer than 50 employees in the country—46 percent—as well as greater concentrations of workers in industries that are less likely to offer health coverage.

Since the late 1990s, employer-sponsored coverage has dropped in every district state except North Dakota, where employment has been buoyed by strong growth in oil drilling. The recession exacerbated this long-term decline, taking a toll even in North Dakota. Many companies laid off workers or cut back their hours, making them ineligible for coverage.

“With close to 10 percent [national] unemployment, it means a lot of people have lost their health benefits along with their jobs,” said Sara Collins, an economist with the Commonwealth Fund, a health care research organization based in New York City. In addition, sagging revenues led some firms to cancel their health policies, obliging employees who wanted to stay covered to buy expensive individual insurance or enroll in government programs.

But long before the recession, rising insurance premiums had been eating away at workplace coverage. Over the past decade, U.S. health care spending has increased about 7 percent annually, partly because the population is aging. In 2009, private medical expenditures in the United States surpassed $1.2 trillion—about 8 percent of gross domestic product—according to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Premiums for employer-sponsored coverage vary from state to state because of different consumer preferences, state-mandated benefits, types of medical providers and other factors. But every district state has seen big premium increases, according to an AHRQ annual survey of medical expenditures. From 2003 to 2009, price increases easily outstripped inflation (see Chart 3).

Although premiums for workplace coverage appear to have moderated recently—average total family premiums actually fell in three district states from 2008 to 2009—insurance prices continue to rise in many markets, inducing some employers and workers to drop coverage. Small employers in particular continue to find health insurance for workers an expensive proposition (see “A small problem”).

Health insurance coverage by the numbers

Sharing the pain

Efforts by insurers and employers to buttress health insurance coverage have focused on reducing insurance premiums. For many employers, that has meant cost sharing—offering high-deductible policies that require covered workers to pay a sizable portion of medical expenses out of their own pocket before coverage kicks in.

The AHRQ medical spending data show clearly how employers have embraced high-deductible plans in response to climbing premiums—average deductibles for employer-sponsored family coverage have also risen (see Chart 4). From 2003 to 2009, average family deductibles rose 35 percent nationwide, adjusted for inflation; in Wisconsin, over the same period, the average family deductible increased 55 percent in constant 2009 dollars, to almost $1,900.

Participation in consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs)—high-deductible plans that let enrollees pay out-of-pocket expenses with pretax dollars—has grown rapidly over the past five years (see page 5). Stephen Parente, a professor of health finance at the University of Minnesota who has done research on CDHPs, believes that without these plans and other high-deductible policies, many employers would have cried uncle and dropped coverage. “If they did not have high-deductible plans available to them, there would be a higher likelihood of people being uninsured through the employer market,” he said.

High-deductible plans offered by insurers in the individual market have also helped to limit premium increases for the self-employed and other people without access to employer-sponsored coverage. However, high-deductible plans have been criticized for their skimpy coverage and the incentive they give people to skip preventive care.

Self-insuring is another strategy used by employers to exert more control over plans and cut regulatory costs.

By self-insuring—paying medical claims themselves, often with the help of a third-party administrator—employers avoid state oversight and certain regulatory costs that they would otherwise have to pay when purchasing coverage from a commercial insurer. There are no federal taxes on self-funded plans, and federal law gives employers wide latitude in designing insurance packages—what benefits employees receive and how much they pay out of pocket for health care.

Self-insuring has long been popular among large employers—they have more workers over whom to spread the claims risk—but more mid-sized firms are self-funding in a bid to trim costs and sustain health coverage for employees. A 2010 national survey of health benefits by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research & Educational Trust found that 58 percent of covered workers at firms with 200-999 employees were in partially or completely self-funded health plans. That’s 5 percentage points higher than in 2007.

In Minnesota, surveys by the state Department of Health show an increase in self-funded coverage since the late 1990s. Firms with at least 100 employees have contributed to that trend, said Bob Johnson, president of the Insurance Federation of Minnesota, a trade association representing insurers in the state. “As [health care costs] have gone up, smaller employers look to self-funding because they may be able to save 3 to 5 percent” on one of their biggest business expenses, he said.

It’s difficult to tell whether or to what extent cost-control efforts by insurers and employers have affected private health insurance coverage. The fact remains that employer sponsorship has continued to drop, although it may rebound as hiring picks up in a resurgent economy.

Moreover, individual insurance hasn’t compensated for the decline in workplace coverage; the proportion of nonelderly people covered by policies they purchased themselves has declined nationally and in most district states over the past decade.

The public option

Low-wage workers who aren’t offered insurance, the long-term unemployed and other low-income people often turn to the government to provide health coverage. In this country, public insurance programs originated in the 1960s, when Congress established Medicare and Medicaid to cover the aged and the poor, respectively.

In the district, state programs aimed at assisting the uninsured differ widely in intent and scope. North and South Dakota and Montana have long pursued a conservative strategy in providing a public option: State funding of Medicaid (technically a social welfare program, not insurance) at close to the federal minimum covers children and pregnant women in low-income households, but serves a much smaller proportion of parents and childless adults.

In South Dakota, for example, to qualify for Medicaid, parents must have monthly incomes less than half of the federal poverty level ($1,863 for a family of four). The U.S. average income limit for parents in 2009 was 66 percent of FPL, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Adults without children aren’t eligible at all. Despite these restrictions, Medicaid enrollment in the state rose 45 percent during the recession, to 96,000 in 2009. (Every district state saw increases in Medicaid enrollment over that period—see Chart 5.)

Montana’s eligibility rules for Medicaid are even more rigorous—incomes less than a third of FPL for parents (single adults are ineligible). “The target population for Medicaid coverage in this state is pretty limited,” said Wendy Doely, executive director of Flathead Community Health Center, a Kalispell clinic that sees a lot of low-income patients. “If you’re 25 years old and not pregnant, you’re probably not going to get Medicaid.”

But in recent years, as workplace coverage has fallen, state government in Montana has taken additional steps to boost health insurance coverage. In 2008, voters approved an initiative to expand coverage for children, tapping insurance premium tax revenue. Last fall, nearly 80,000 Montana children were enrolled in the Healthy Montana Kids program, which receives federal matching funds under Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Insure Montana, administered by the State Auditor’s Office, subsidizes employer-sponsored coverage by firms with fewer than 10 employees. One part of the 5-year-old program defrays premium costs for firms that offer health insurance for the first time through a state purchasing pool or affiliated health plan. As of January, 872 businesses were enrolled in the pool, which state officials credit with extending health coverage to over 4,400 employees and their dependents. A tax on tobacco products funds both the pool and another part of the program that gives state income tax credits to firms that already offer insurance.

A wider safety net

In Minnesota and Wisconsin, policymakers have gone to greater lengths to provide an alternative to private insurance coverage. Compared with the Dakotas and Montana, and the nation, these states set higher income ceilings for Medicaid eligibility and sponsor additional programs for low-income people who would be denied public support elsewhere.

In Wisconsin, state government has set a goal of ensuring that at least 98 percent of the state population has access to affordable health coverage. To that end, the Legislature in 2007 enacted BadgerCare Plus, an enhanced Medicaid program that provides coverage for about 770,000 people in low-income households. Adults with incomes up to twice the FPL receive an array of health services, with childless adults (added to the program in 2009) getting more basic care, including preventive treatment and drug prescriptions.

Minnesota also “has made it a priority to provide access to coverage for its citizens,” noted Julia McCarthy, outreach manager for Portico Healthnet, a St. Paul agency that helps people obtain health coverage.

Since the early 1990s, MinnesotaCare has offered public insurance to people who make too much money to qualify for Medicaid but lack private coverage. Enrollees—including parents with incomes up to 275 percent of the FPL—pay premiums based on a sliding income scale and co-pays for certain services such as inpatient hospital stays and nonemergency ER visits.

Enrollment in the program, which is almost two-thirds funded by premiums and state taxes on insurers and health care providers, shot up during the recession. In January, about 164,000 people were covered by MinnesotaCare—a 39 percent increase over the average monthly head count in 2007.

Minnesota has also expanded Medical Assistance (the state’s brand of Medicaid) to cover working-age adults without children living below the poverty line. The federal health care law enacted last year makes low-income single adults eligible for Medicaid—but not until 2014 in most states. In January, Minnesota was one of a handful of states to enroll early in the federal expansion, a move that is expected to add about 95,000 adults to the Medicaid rolls this year.

Benefits and costs

There’s little doubt that public insurance programs in these states have prevented further increases in the number of uninsured due to the recession and higher insurance costs. A fedgazette analysis of Census data estimates that in Minnesota, increased enrollment in Medicaid and MinnesotaCare between 2007 and 2009 amounted to almost 4 percent of the nonelderly population. In Wisconsin, a wave of Medicaid (including BadgerCare Plus) signups over the same period more than offset a decline in private coverage.

However, this accounting doesn’t reveal whether all the new Medicaid enrollees would have remained uninsured if the program weren’t available. There’s the rub with public health insurance: Some firms and workers may opt to drop workplace coverage, preferring to shift insurance costs to taxpayers. Likewise, the unemployed or low-wage workers who aren’t offered insurance by employers may spurn individual policies in favor of cheaper public programs. In either case, some increased enrollment in public programs comes at the expense of private coverage instead of reducing the number of uninsured.

There’s anecdotal evidence of such “crowding out” of private insurance in some states. In Massachusetts, insurance brokers reported last year that some small businesses had dropped coverage and encouraged workers to enroll in Commonwealth Care, the state’s subsidized insurance program.

But economic studies of state-sponsored insurance programs have found mixed evidence for crowding out. A 2006 study by researchers at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., concluded that expanding coverage to parents in California and New Jersey eroded private coverage. Other studies have indicated that the degree to which it occurs depends on how public insurance plans are designed.

MinnesotaCare and, to a lesser extent, BadgerCare Plus, have provisions intended to prevent inroads into private coverage. MinnesotaCare applicants, for example, are ineligible if they’ve been offered workplace coverage anytime in the last 18 months. How successful these measures are at preventing crowding out is unclear.

For state lawmakers, a more pressing issue raised by expansive public insurance programs is their costs. Spending on such programs in Minnesota and Wisconsin dwarfs state government outlays in other district states, both in absolute dollars and as a share of the total state budget. For example, Medical Assistance and other government insurance programs cost Minnesota taxpayers about $3.4 billion in fiscal 2010—roughly 17 percent of overall state spending. That level of expenditure is more than three times what residents of the Dakotas and Montana pay, in proportion to total state spending.

Strained budgets due to lingering economic malaise have made it harder for states to justify continued support for expensive public insurance coverage. In Wisconsin, enrollment in the BadgerCare Plus Core plan for childless adults was frozen in 2009 because of a state Medicaid deficit; this past February, the deficit stood at $153 million for the 2010-11 biennium. Roughly 100,000 applicants are on a waiting list. In Minnesota, state budget woes have cast doubt on the state’s ability to continue to fund MinnesotaCare and the expanded Medicaid program.

Even district states with less costly public health plans are reevaluating their commitment to covering the poor. In South Dakota, lawmakers are weighing a proposal by Gov. Dennis Daugaard to slash state Medicaid reimbursements to providers by 10 percent. Such a cut could induce some doctors and clinics to turn away Medicaid patients.

ACA: An uncertain prognosis

In any discussion of health insurance, one topic dominates: the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, enacted by Congress a year ago. The law has provoked staunch opposition; the Republican-controlled U.S. House has vowed to repeal it, and attorneys general in Wisconsin, North Dakota and South Dakota are involved in federal lawsuits challenging its constitutionality. These and other district states may reject some or all aspects of the federal effort to revamp the health care system.

If ACA is fully implemented—its major provisions go into effect in 2014—analysts expect it to significantly increase health insurance coverage. In the district, the impact of enhanced Medicaid coverage, an individual mandate to buy insurance, subsidies for small businesses and other features of the law will be greatest in states such as Montana and South Dakota that currently have relatively high rates of uninsured. But the degree to which ACA will boost coverage in the district is as uncertain as the prospects for survival of the law itself.

One large and predictable effect of the law is expanded public coverage for low-income people. In 2014, all states will be required to meet a new income eligibility standard for Medicaid: Parents and childless adults may have incomes up to a third above the FPL to qualify for aid. The new standard will dramatically loosen Medicaid eligibility requirements in Montana and the Dakotas, where a sizable portion of the nonelderly population falls below that income threshold.

An analysis of the impact of ACA on Medicaid coverage by the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that in South Dakota, the law will add 31,000 people to the state’s Medicaid rolls by 2019, reducing the number of low-income uninsured adults by more than half. Montana would see a slightly smaller proportional drop in uninsured adults below 133 percent of the FPL.

But health policy experts expect the Medicaid expansion to increase coverage to a lesser extent in Minnesota and Wisconsin, where eligibility ceilings for Medicaid and other public insurance programs are higher. In Minnesota, many low-income people currently enrolled in MinnesotaCare may switch to Medicaid under ACA—saving them premium expenses but not shrinking the number of uninsured in the state.

To what extent the law will stimulate or erode private health coverage in district states is harder to gauge. Much depends on how individuals and firms in different markets respond to the various incentives and penalties embedded in the law.

As its creators envisioned, ACA may increase private coverage by fostering competition, rooting out inefficiency and encouraging individuals and small businesses to buy insurance.

Beginning in 2014, individuals and small businesses will be able to purchase insurance through regional health care exchanges, marketplaces set up by states to certify health plans and allow consumers to directly compare benefits and prices. Federal tax credits will subsidize premiums for individual policies purchased by lower-income people through exchanges.

However, market responses to the law may partially offset gains in private coverage due to tax breaks or more transparent prices, or even reduce private coverage. For instance, some people—particularly those whom Johnson of the Insurance Federation of Minnesota calls “the young and invincible,” may opt out of the individual mandate, preferring to pay a penalty instead.

And employers struggling to pay insurance premiums might drop coverage, leaving employees to shop for subsidized insurance in the exchanges or sign up for Medicaid. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that 8 million to 9 million workers nationwide—mostly in small firms that pay low wages—will lose their workplace coverage because of such cost shifting under ACA.

Hey, if they can cure cancer …

Paying for health insurance—both private and public—is likely to become more difficult if health care costs are not contained. Rising health care expenses put upward pressure on premiums and out-of-pocket expenses, making coverage more expensive for employers and individuals. Higher costs also increase the burden shouldered by taxpayers to support public insurance programs such as Medicaid and MinnesotaCare.

But cutting health care costs is a tall order because trends in the sector, including expensive new medical technology and a wave of aging baby boomers with chronic diseases, are pushing in the opposite direction. “Cost pressures are going to continue to erode the market,” said Jean Abraham, a health insurance expert at the University of Minnesota.

Short of some medical breakthrough like curing diabetes or heart disease, the most likely path for reining in health care costs is to chip away at the margins—employing a variety of strategies that not only shift costs or cut regulatory expenses, but also achieve measurable reductions in spending on medicines and treatments.

Recently, insurers have started to pay incentives to medical providers that succeed in cutting costs while keeping patients healthy. In Minnesota, HealthPartners, Medica, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield—the three biggest health insurers in the state—have signed such incentive contracts with providers over the past three years.

Other approaches to reducing medical expenditures and insurance premiums include corporate wellness programs and value-based insurance design—lowering deductibles and co-pays for medicines that keep patients with serious, chronic illnesses out of the hospital.

But none of these strategies has a long enough track record to show that it can significantly reduce health care costs, keeping insurance premiums in check. “I don’t think there is any single magic bullet for slowing the growth of health care costs,” Abraham said. “These are incremental changes.”