If you’re a professional in the commercial real estate industry, it’s probably akin to being locked in a car, with no steering wheel or brakes, heading into a potentially violent, slow-motion crash.

Commercial real estate (CRE) is that part of the economy involved in imagining, financing, building and managing the offices, production plants, storefronts and other businesses that drive much of the economy.

CRE has been making a lot of news lately, and for all the wrong reasons. Much like its residential sibling, it experienced a boom through the middle part of this decade and is now facing the ramifications of that excess. Vacancy rates across the district are rising—often steeply—in office, retail and other CRE submarkets. That’s pushing down rents and putting new CRE projects in a deep freeze, among other problems.

As a senior vice president for CB Richard Ellis, an international real estate services firm with offices in the Twin Cities, Murray Kornberg has watched both the huge run-up in the CRE market during the past decade and, in his words, the “nuclear winter” currently gripping the sector. “We were going fine and then fell off a cliff.”

The industry faces the prospect of widespread defaults, thanks to a triple whammy of slack demand, plummeting prices and tight credit—a rolling real estate snowball that offers challenges not only to property owners, but investors that financed the boom in the first place. As a result, a badly suffering CRE industry is on the minds of investors, in the speeches of regulators and virtually the only topic of conversation at industry mixers.

CRE borrowers face two different, but related, challenges. Most obviously, the recession is making life difficult for many businesses. As businesses close, vacancy rates for office, industrial and retail properties are rising, and building owners are having trouble keeping enough cash flow to meet their mortgage payments.

The other challenge is a quirk of boom financing during the CRE heyday, when real estate prices and transactions rose steeply. Investors competing to finance the CRE boom locked in loans at fast-rising values with relatively short—and now, ill-timed—maturities. A throng of CRE loans now face maturity with no clear resolution. Property values have plummeted, putting many CRE loans at a loan-to-value ratio that’s too high to refinance. And investors, including lenders, have tightened credit across the board (see related story for more discussion of banks and their CRE loans).

Investors and borrowers alike are searching for escape hatches. While certain options, like loan extensions and other modifications, might be appealing and ultimately helpful given the circumstances, none is without risk; at best, they might lessen collateral damage as investors and borrowers nervously await recovery in CRE markets and the economy more generally.

How did we get to this place?

First, a few formalities. There is no tight definition of “commercial real estate” among the various sectors involved in this market. In general, the term is meant to refer to buildings and other property used by owners to generate profit from either space rental or property appreciation. For this article, “commercial real estate” refers to (but is not necessarily limited to) buildings and other property used for industrial, office, retail, medical or educational purposes, as well as residential properties having more than four dwelling units. That definition changes slightly for what banks and their regulators define as CRE lending. (See CRE: The cracked glass slipper? for more discussion.)

Now, back to the journey taken by the commercial real estate sector this decade. Its current position is not particularly difficult to trace. The industry witnessed significant new development, as well as heavy buying and selling of existing properties, through about 2007. Both trends boosted overall demand for CRE and sent related property values skyward.

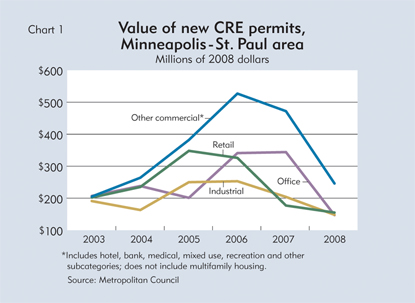

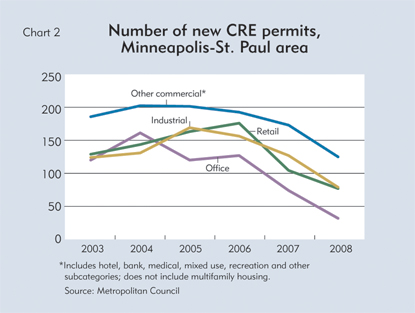

In the seven-county Twin Cities region—far and away the largest market in the Ninth District—both the value and number of building permits for new office, retail, industrial and other CRE projects saw robust activity through 2006, and even 2007 wasn’t a terrible year in terms of permit value (see Chart 1 and Chart 2).

CRE Roller Coaster

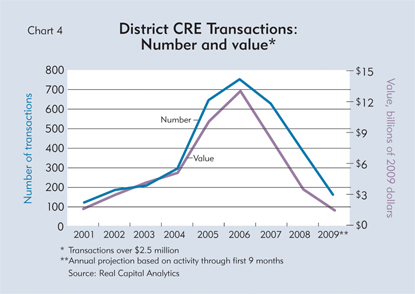

On top of new development, CRE properties saw a dramatic increase in the number and value of transactions, as property owners used favorable lending conditions to refinance properties and investors used an appreciating market to make money buying and selling properties. During this period, retail and office saw particularly heavy action in the district. In Minnesota, for example, the value of retail CRE transactions rose from $200 million in 2001 (inflation-adjusted) to more than $3 billion by 2006, according to data from Real Capital Analytics, a real estate research firm that tracks transactions and other activity; office sales went from $250 million to over $2 billion.

All of this CRE activity—lots of new development and high demand for existing properties—had the effect of driving up CRE values. In Hennepin County, home to Minneapolis and its suburbs, the estimated property value of commercial and industrial land increased almost 50 percent between 2003 and 2008—to almost $30 billion, according to figures from the county’s most recent comprehensive annual financial report. That’s an even faster pace of appreciation than housing experienced during the same period.

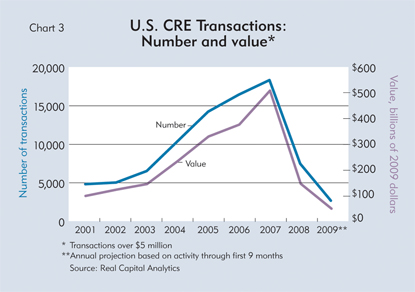

But in a cliché that was surely thought up by the real estate industry, what goes up eventually comes down, oftentimes hard. Starting in 2007, CRE started to soften and then turned downright squishy by 2008. CRE transactions nationwide plunged off the cliff, while district transactions merely fell down a steep hill (see Chart 3 and Chart 4).

U.S. and District CRE Transactions Fall

New CRE development also slowed dramatically. In the Twin Cities region, total CRE permits fell by more than half (53 percent) from 2006 to 2008, and a variety of sources show that 2009 has been worse. In Minneapolis, for example, there were 15 commercial building permits in the first half of 2009 exceeding $1 million in value, compared with 42 in the first half of 2006, according to city figures.

Most of the district played follow-the-leader. The city of La Crosse, Wis., approved 23 commercial and industrial permits in 2007, according to city officials. In the subsequent 22 months (through early November 2009), the city approved just 20 projects. In Marquette County, home to the largest city in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (Marquette), permit activity hit 31 in 2007, according to Eric Anderson, a county senior planner. Through October of 2009, just 15 permits had been issued. More notable was the drop in permit value, which dried up from $47 million to just $4 million.

The CRE market in Billings, Mont., has lagged the rest of the district, in part because the entire state felt the effects of the national recession later than the rest of the country. Billings saw continued growth through 2008, but activity was cut roughly in half in 2009, according to Mary Bradley, the city’s permit coordinator. Commercial permits through October of 2009 fell to 40, compared with 75 for the same period a year earlier. Permit value dropped from $85 million to $45 million.

Real estate booms and busts are hardly novel. What is new today is the potential depth of the problem, caused by the fact that many CRE borrowers face two solvency challenges: The first and most obvious one for a commercial property owner is not being able to pay the mortgage, which happens if tenants are struggling and behind on their rent or go out of business altogether and the space becomes vacant and earns no revenue.

And that’s happening. Vacancy rates are rising across the district and in most submarkets like retail, office and industrial. Colliers Turley Martin Tucker, a national CRE firm with an office in Minneapolis, said in a report on third-quarter conditions that office and industrial vacancies in the Twin Cities hit 19.6 percent and 12 percent, respectively—both up a couple of percentage points since the end of 2008.

Office vacancy in the Sioux Falls region hit 16 percent in 2009—the first time in history the city’s vacancy rate exceeded the national rate, according to Douglas Brockhouse, a principal with Bender Commercial Real Estate Services, via e-mail. He added that the firm isn’t involved with financing, but he knew of a number of developers that reportedly have “handed the keys to properties to the banks and told them to figure it out.”

Compounding the problem is that property owners have had to start discounting rent to attract new lessees, which also gives an incentive to existing tenants to ask for lease concessions or go looking for new space. Rental rates on the best office space in Sioux Falls have dropped from $15 to $11 a square foot, according to Brockhouse. Industrial vacancy remains under 5 percent, yet rents dropped about 20 percent over last year.

Jim Villa, president and CEO of the Commercial Association of Realtors Wisconsin (CARW) said that the state’s office market is seeing vacancies rise and rents fall, “and property owners are struggling to hold clients.” It’s affecting new development as well, as many firms are considering contracting existing space because of their leverage in a soft market, rather than expanding facilities or building anew.

Maturity default

The second challenge facing CRE owners might seem more mundane, but is potentially more ominous. It involves the maturing of existing CRE loans.

To understand the predicament, first go back to the boom years. Strong demand meant that many new developments and existing properties were getting financed or purchased at rapidly rising prices and on terms much shorter than residential mortgages—typically five to 10 years and even shorter for booming construction and land development loans.

Now fast-forward to the present. A wave of CRE loans from the gravy years are maturing, or coming due. Unlike most home mortgages, where the buyer makes monthly payments until a loan is paid off, a commercial real estate loan typically involves monthly payments followed, at the maturity date, by a large equity balloon payment for the balance of the loan. Often these loans simply get refinanced or are paid off through a new loan from a different bank or through the sale of the property to an interested investor.

But these loans only get refinanced (or picked up by other lenders or paid off through a property sale) if the collateral property retains its appreciated value. And that’s not happening. In a replay of the housing collapse, CRE values have crashed since 2007. How much is difficult to say, because each market is unique and there are few concrete data on such matters, especially at the local level. Nationwide, prices have reportedly declined between 25 percent and 40 percent since their peak in the fall of 2007, according to various sources, and market conditions suggest that they will fall further. In the district, declines are expected to vary widely, depending on the health of the local market and the degree of price appreciation during the boom.

Falling property values means that many maturing CRE loans are underwater—borrowers owe more in loan principal than the collateral property is worth—and few property owners have cash on hand to meet the balloon payment; if they did, few would likely leverage it in a market that many believe has not yet hit bottom. Even on loans that retain some equity, loan-to-value ratios are typically too high for either the current lender or a prospective new one to extend credit.

In other words, it’s a classic boom trap. The magnitude of the maturity risk is difficult to peg. US Bank estimated in 2009 that CRE loans worth $271 billion were maturing in the United States, a rising tide that is expected to reach $600 billion by 2017. Daniel Tarullo, a governor on the Federal Reserve Board, has estimated that almost $500 billion in CRE loans will mature each year over the next few years. Of course, not every maturing loan will be in an equity pickle. But according to Foresight Analytics, a California-based real estate consulting firm, about $770 billion in commercial mortgages set to mature in the next five years are currently underwater.

A fuzzy elephant

The district picture is more difficult to discern. According to a Federal Reserve Board analysis (using data from Real Capital Analytics), the number of CRE properties in distress as of October was lower in the Ninth District than in any other Federal Reserve district, and the total value of those distressed properties was the second lowest of the 12 Reserve districts. But the RCA database tracks only higher-value properties and transactions, of which there are comparatively few in the largely rural Ninth District.

But there is widespread evidence of CRE problems in the district. Jill Rasmussen is a principal at the Davis Group, a small CRE firm in Minneapolis, and has 25 years of experience in the office and health care sector. She said she knew of “several large properties” that were purchased in the Twin Cities at high values and now have maturing loans. “The values of these properties have declined, and refinancing will be very challenging or impossible,” Rasmussen said.

Brockhouse, from Bender Commercial, said there were too many underfunded investors in a growing Sioux Falls market that developed properties “that were not preleased or were leased to companies that never had a chance of fulfilling their lease obligations.”

In a soft market, property owners have been forced to renegotiate leases to maintain sufficient cash flow and make monthly payments. But the resulting drop in property income means that loan-to-value ratios “have gone out the window,” Brockhouse said. “When it comes time to renegotiate a new loan, every one of them is going to have to write a significant check to bolster the equity that they have in the property. The problem is that the landlord-investors don’t have the capital to write those checks.”

That problem is exacerbated by the fact that credit has tightened from all financing sources, including banks. According to nationwide quarterly surveys of senior loan officers by the Federal Reserve, CRE loan standards were tightened by about 80 percent of responding banks in all four quarters of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009. By the second quarter of 2009, those figures started to come down and stood at 35 percent in the third quarter (October) survey. That’s better, but banks indicated that current lending standards were still much tighter than average levels over the long term.

District sources widely reported that borrowers—even new buyers looking to scoop up good deals—were facing much higher equity demands to get a CRE loan; during the boom, a borrower could expect to borrow up to 90 percent of a property’s collateral value. Today, lending limits are being set at about 65 percent of an already depreciated asset. “One thing buyers need is cash, and lots of it,” said the Colliers report on third-quarter conditions. “With the continued tight credit markets, banks require more money down to make a deal happen. Unfortunately, very few companies have the luxury of holding extra cash.”

Kornberg, from CB Richard Ellis, sees a “big maturity risk” in the market because of the scarcity of credit. Many loans are healthy and performing well, but at maturity “they don’t have the equity to get the [refinancing] job done,” he said. “I don’t believe banks are walking away from good deals. But if you’re going to make a loan in this environment, the deal better be very good.”

That mentality shows up in the data. According to a third-quarter 2009 survey by the Mortgage Bankers Association, commercial and multifamily mortgage loan originations in the third quarter were 12 percent lower than in the previous quarter and 54 percent lower than in the same period in 2008.

Villa, from CARW, said Wisconsin has “a growing problem of properties facing loan maturity and not being able to find a lending institution to rewrite the loan. … For the most part, brokers and owners are saying it has become extremely difficult to find refinancing.”

CRE borrowers also have fewer financing options than during the boom. For example, through 2007, ample credit was available through commercial mortgage-backed securities—CMBS, the same mortgage-finance tool that created the subprime mortgage frenzy and played a lead role in the housing collapse. During the boom, CMBS financed about one-quarter of CRE deals, peaking at $250 billion in 2007, and then crashed back to “not one dime this year,” Kornberg said. “That’s a supernova.”

Though CMBS financing is believed to have been used much less often in the district, and district banks hold comparatively little CMBS debt on their books, capital is nonetheless finite and mobile, and the implosion of CMBS shrank available capital and increased competition nationwide for what remained.

In short, CRE financing has morphed from easy money at inflated prices to hard money at depreciated values.

Fork in the loan road

The path out of the CRE woods is not particularly clear. Already, CRE loan delinquencies are increasing (see CRE: The cracked glass slipper?), and the number of properties facing loan maturity is reportedly climbing in step with the previous rise in total financings during the boom. Given the circumstances, borrowers facing either term or maturity default are hoping for patience from banks and other sources of CRE financing.

From a lender’s standpoint, both term and maturity defaults offer a choice between two unsavory options. Foreclosure is the most obvious option, and a good one to ensure that lenders recover some of their investment.

Another option involves refinancing or modifying a loan with new terms (including a maturity extension) in hopes that an economic rebound will allow borrowers and properties the ability to make their way to the proper side of the ledger. Such a strategy can offer safe harbor for those needing some time to rebound with a recovering economy, as well as for those already performing well but facing an equity gap.

Without necessarily approving of these so-called loan workouts, bank regulators, including the Federal Reserve, issued guidelines this past fall that encourage lenders and borrowers to modify loans where appropriate and prudent. The IRS also issued changes regarding its view of bank loan modifications. Taken together, some believe these regulatory moves offer much-needed flexibility for borrowers and lenders alike while the economy and the CRE market stabilize and allow the CRE conflagration to become more a controlled grass fire than a scorched-earth forest fire.

Villa, from CARW, said, “I don’t think a significant percentage of properties will end up in default.” Many might approach default, he said, which would give both borrower and lender the incentive to be creative. “Will you see a double-digit increase in the percentage of properties going into default in 2010? I think it’s possible, but more likely I think people are going to be working with lenders to bridge the gap creatively [by finding mutually beneficial ways to modify or extend loans] between now and when the credit markets loosen up again.”

Between a rock and a soft loan

Nonetheless, the biggest problem for property owners and their debt holders is a CRE market that’s predicted to get worse before it gets better. Heavy job losses, high vacancy rates and tight credit have created the rolling CRE snowball. Regardless of loan workouts, the amount of distressed property is expected to increase, keeping supply high and reinforcing the lid on any value appreciation.

As such, while the regulatory flexibility might help, the real key will be the timing and pace of recovery in the CRE market. Unfortunately, most sources aren’t particularly optimistic on that front. A midyear report on the Twin Cities market last summer by Northmarq, a regional CRE firm, said, “It’s clear that the market will see an increase in distressed ownership situations during the second half of 2009 and into 2010 as more landlords face cash flow problems” while dealing with pressure from their lenders.

In a nationwide recap of third-quarter sector performance, CB Richard Ellis said the office market was simply “another quarter closer to the bottom.” In its annual emerging trends report, released in November, the Urban Land Institute said rents would fall and vacancies would rise this year, and a “lackluster” economic and job recovery means that the CRE market “probably cannot gain much traction until late 2011 or 2012.” And for struggling property owners, the report said that this year “will be the worst time for investors to sell” in the report’s 30-year history.

Kornberg and others say the key will be job creation, because it drives everything in CRE. “If we can’t create jobs, we won’t have demand for space.”

Unfortunately, the job outlook is shaky. Future hiring is expected to grow much more slowly than recent job firing. For example, in the 12 months ending this past October, employment in Minnesota fell by 100,000 workers—or about 4 percent of total employment, according to state figures. If job growth rebounded to equal the state’s historic average (just over 1 percent annually), it would take almost four years for employment to regain its October 2008 levels. Unfortunately, forecasts by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and other organizations predict much more sluggish employment growth in coming years (see the 2010 employment forecast). That doesn’t bode well for vacancy rates, rent and new CRE development.

Compounding the problem is an abundance of “shadow space”—space that is leased but underutilized—that will need to be absorbed before real net absorption happens. Many firms have slashed employment and production, which means they have space available to grow operations once the economy and hiring kick back in. A report this past summer by Colliers said that shadow space could delay real recovery by 12 to 24 months.

Still, some sources are guardedly optimistic. Kornberg feels that the CRE problem is both smaller and simpler than the subprime mortgage disaster. “The degree of lunacy in subprime got way ahead of the lunacy of CRE,” he said. Maturity default is a real problem for CRE, he said, but it’s easier to deal with than the subprime mess, which gave home loans to some buyers who never had the means to pay their bills.

Moreover, lenders literally own part of the CRE problem, unlike subprime home loans that were sold by lenders into secondary markets. That means lenders have to worry about preserving the value of their collateral—commercial property. As a result, “I am not seeing a wave of maturing loans default,” Kornberg said. “I have to feel that way, or I wouldn’t be able to get up in the morning.” Instead, he predicts a wave of loan extensions because, as one of his peers told him, “a rolling loan gathers no loss.”

“Have we hit bottom? No,” said Kornberg. But, he added, unlike what many once believed, “we’re not going into the chasm.”

Associate Economist Daniel Rozycki and Economist Mark Lueck contributed data and analysis to this article.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.