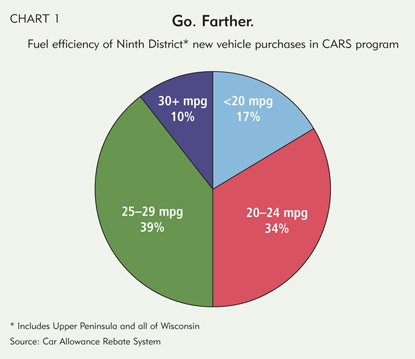

Though the federal cash for clunkers program was controversial in terms of economic utility, it offers some interesting economic tidbits on consumer behavior and on upgrading the fuel efficiency of the automotive fleet in the Ninth District.

The program, officially called the Car Allowance Rebate System, offered vehicle owners the chance to get up to $4,500 knocked off the sticker price of a new vehicle for trading in an older, less fuel-efficient one. With the dust settled, it appears that sales varied widely in district states, and while the program managed to increase overall fuel efficiency, the gains from many transactions could be considered quite modest, particularly given the buyer subsidy.

Overall, more than 40,000 cars, trucks and SUVs were purchased in the Ninth District (including the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and all of Wisconsin). That’s almost 6 percent of the 677,000 incentive transactions throughout the United States. Participation rates varied; about one in 300 licensed drivers nationwide took advantage of the purchase subsidy. That compares with about one for every 225 licensed drivers in the district. That might not sound like a big difference, but dealers would have sold 10,000 fewer vehicles had the district rate mirrored the nation’s.

Consumers were also more eager in some district states than others. For example, Montana was the only district state with a lower clunker participation rate than the national average; in fact, participation on a prorated basis was less than half that of any other district state, at about one for every 500 licensed drivers. At the other end, Minnesota participation came in at one for every 185 licensed drivers (see table).

There are likely a handful of reasons participation rates varied among states. For starters, the number of vehicles per registered driver is higher in Minnesota than in other district states, as well as in the nation as a whole. This means Minnesota probably had more eligible clunkers per driver.

But there are also some mysteries, like Montana’s low participation rate. The state’s rate of vehicle ownership per licensed driver is on the low side among district states (see table), but it is actually higher than the national average and does not point to an obvious deviation in car ownership habits.

Given the program’s uniformity of (demand) incentives, it’s worth looking at whether some supply-side effects influenced clunker participation rates. For example, did consumers have ample access to the program via dealerships? On the surface, at least, it appears they did; in Montana, there is one dealership for every 7,425 residents versus one dealership for every 12,600 people in Minnesota.

But vehicle inventory might have been a key, at least in Minnesota. Scott Lambert, head of the Minnesota Automobile Dealers Association, said dealers in his state “made a strategic decision” to aggressively promote the incentive program to potential buyers. “They loaded up on inventory and took out lots of full-page ads” to get the word out, he said. The added inventory cost millions, and dealers also had to shoulder the initial cost of the incentive before getting reimbursed by the federal government.

“It was a huge risk to order inventory, and other parts of the country didn’t do that,” said Lambert. But it paid off for Minnesota dealers, he added, because the program initially did not allow back-ordered vehicles to qualify for the subsidy. As a result, “if you didn’t have inventory on the ground, you were out of luck,” he said.

Dealers also thought they might see a lot of potential buyers with bad credit; instead, said Lambert, “they came with beat-up cars and great credit,” which translated into many sales.

Fuel, if maybe not economic, efficiency

Average fuel efficiency between trade-ins and newly purchased vehicles rose about 50 percent, from roughly 15.5 miles per gallon to 24.

But that covers up a lot of variation, part of which suggests a sop to owners of older, typically larger vehicles who used the opportunity to upgrade to something with only marginally better gas mileage.

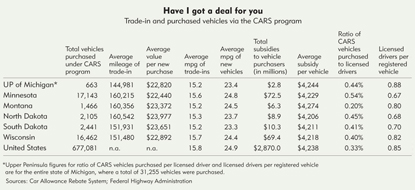

For example, about one quarter of the new vehicles purchased through the clunker program in the Upper Peninsula and the Dakotas had fuel efficiency gains of four miles per gallon or less. In many cases, older trucks and SUVs were simply traded in for newer but only marginally more fuel-efficient versions. Only 10 percent of all vehicles bought in the district under the program got 30 mpg or better (see Chart 1).

At the same time, even seemingly meager improvements shouldn’t be dismissed, because upgrading the fuel efficiency of a gas guzzler by just a few miles per gallon saves an enormous amount of fuel; in fact, a driver saves more fuel by going from 10 mpg to 14 mpg than by upgrading from 20 mpg to 30 mpg (286 versus 167 gallons of gas saved for every 10,000 miles, respectively).

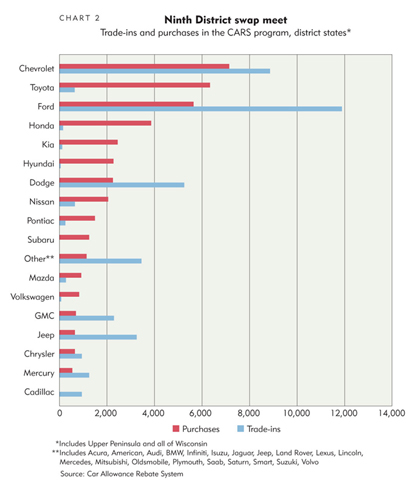

It’s also interesting to note the brand shift among vehicle owners. By large margins, the most common trade-ins were Ford, GM and Chrysler brands—a result of the stated goal of removing older, gas-guzzling trucks and SUVs (a market dominated by those firms) from the road. Though Ford and GM also netted significant sales of new vehicles, so did foreign-owned competitors like Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Nissan and Toyota (see Chart 2).

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.