In late December 2008, the Minneapolis Police Department held a press conference to announce a major achievement. For the second year in a row, the city had experienced a double-digit reduction in crime. Since 2007, violent crime had dropped 13 percent; compared with 2006, it was down 24 percent. Homicide—the most brutal component of the violent crime category—was down 22 percent in 2008, a 39 percent drop since 2006. Robbery and rape were also down significantly.

Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak praised the police for this accomplishment. He attributed the reductions to better police work, outreach to communities and a focus on juvenile crime prevention. But in the next breath, Rybak cautioned that the trend might not continue.“When the economy is bad,” he observed, “people do desperate things they wouldn’t otherwise do.”

As the economy sours and increasing numbers lose their jobs, more and more voices like Rybak's are warning of the ominous prospect of a return to high crime. Since hitting historic peaks in the early 1980s (property crime) and early 1990s (violent crime), crime rates have dropped significantly in the United States. But many fear that trend will reverse because of the economic recession: Not only will a tough economy push some individuals toward criminal activity, as Rybak suggested, but government budgets will be strained by lower tax revenues, and law enforcement budgets could suffer. Both concerns were voiced by people throughout the district.

But not all see the link as so clear-cut and dire. Yes, budgets will tighten, but public safety won’t necessarily be threatened, according to some. And while desperate times may encourage desperate acts, many criminologists and some police point out that crime rates are influenced by a wide range of factors. Recessions aren’t pleasant for anyone, but concerns about surging crime waves are likely overblown.

The matter is complicated, at least somewhat, by findings from economic theory and empirical research. Though some research supports the conventional view of rising crime during economic downturns, a closer look at theory finds a more complex story, and empirical studies over the years haven’t found as solid a relationship as one might think between economic downturns and criminal activity. Many other factors are at play, from demographic changes and shifting cultural norms to legislative initiatives and technological innovation. Thus, forecasting crime trends—like predicting the weather or the economy—is an uncertain venture.

Criminal tendencies?

There's no question that many law enforcement officials in the district fear that a weak economy will lead to more crime. In Douglas County, home to Superior, Wis., police are concerned about the impact of a recession.

“It can't get better anytime soon, in my opinion, just because you have more and more people who aren’t working; more and more who are losing their homes,” said Douglas County Sheriff Tom Dalbec. “I mean, our foreclosure notices and sheriff’s sales … have gone up pretty drastically.” Dalbec said that property crimes like theft and burglaries are likely to increase in a recession. “It’s more the necessary things that are part of the crimes—food, gas and that type of stuff.”

Lynn Erickson has a similar view. He worked for years in the Williston, N.D., police department; now he’s chief of police in Glasgow, Mont. In both states, he said, bad times mean more crime, and though the recession hasn’t hit Montana as hard as it has some states, he anticipates that it will. Already, crime is trending up as the economy heads down and some people lose their jobs and/or homes, he said. “People are looking at, you know, if they have a family and they’re going to survive, they have to look at any means possible, and I think we are seeing somewhat of a rise in theft and other property crimes” because of that.

Erickson sits on the Montana Board of Crime Control, and its executive director, Roland Mena, is of the same opinion. “We’re not in this recession enough to know for sure; our crime reporting would lag,” Mena said. “But anecdotally, there appears to be more fraud and different kinds of scams that we’re seeing. We're also seeing some increases in larceny and theft over the past quarter. Also, domestic violence becomes a major issue in [difficult financial] times, with stress on families and so forth.”

Still, Mena said that the connection between economic health and crime rates is unclear. “It’s complicated when you look at all the factors that come into play, so there’s no cut-and-dried answer to the [question of] economics and crime trends.”

Cutbacks?

In addition to worries about increased criminal activity, the conventional wisdom also holds that recession-strained government budgets will result in fewer police on the street.

Mike Angeli, police chief in Marquette, Mich., is concerned about the impact a recession might have on his budget. Michigan’s economy has been “in the tank” for quite a while, and revenue-sharing with local agencies has been going down for years. “So we’ve had to cut back in our law enforcement. If it gets worse, it could have an effect [on our ability to fight crime].” State police and sheriff's department staffing has been scaled back considerably, he said, but the Marquette Police Department has been able to maintain staffing, so far, and that’s kept criminal activity outside of town limits. “If our numbers go down, and they know it—the bad guys know it—certain things could develop in town. I do see a relationship there.”Erickson in Glasgow, Mont., is similarly alarmed. “The recession is going to start affecting us, and when it does, it’s going to be a budgetary thing. One thing in my 28 years in this business that I’ve known is that usually law enforcement is the first place they like to cut,” he said. “Do you give up your public works or your law enforcement? Which one are people going to bitch most about? If people have potholes in their street, they’re going to be really mad, but if they don’t see that police car drive by every 15 minutes, it’s no big deal—until it directly affects them.”

Unlike Minnesota and Wisconsin, which face multibillion-dollar deficits over the next two years, Montana will enjoy a budget surplus in 2009, but its projected size has dwindled rapidly over recent months. “We’re starting to get the forecasts that we’re going to be hurt just like everybody else,” said Mena of the Montana Crime Board. “That'll impact local budgets, and certainly law enforcement struggles locally competing with other interests in the community.”

Sheriff Dalbec in Douglas County, Wis., has a pretty good sense of how things might play out there. In setting his 2009 budget, he faced contractual wage increases for his staff of about 2.5 percent and health care costs rising about 10 percent. But the state’s expenditure restraint payment program allowed him to raise his total budget by only 2 percent, “so I’m behind the eight ball going into the budget process based on wages and health care costs alone,” Dalbec said. Thanks to cuts over the previous three years, “if I have to start making cuts for the 2010 budget, it’s going to end up being positions, because I’ve got nothing else left to cut.”

In Minnesota, city administrators are suggesting that police services will be on the cutting block along with everything else as the state’s financial shortfall forces communities to trim budgets. St. Paul had planned to hire 14 new police officers in 2009, but in mid-January Mayor Chris Coleman announced a hold on those hires. In December, Rochester, Minn., city administrator Steve Kvenvold told the Post-Bulletin that he anticipates some level of cutbacks in police services in response to the state’s $1.9 million reduction in local aid to the city.

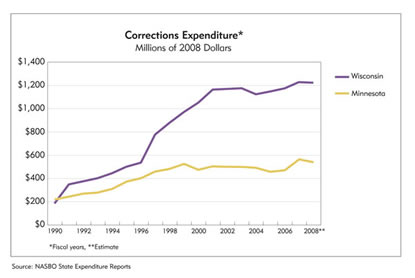

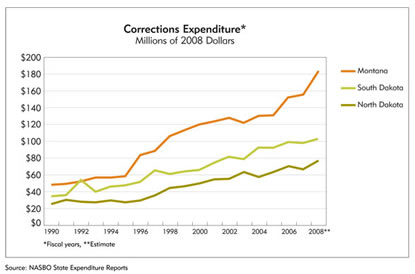

Financial pressures are also hitting farther up the criminal justice ladder. District states vary widely in spending on their prisons, but generally speaking it has been rising. Minnesota expenditure growth has been the slowest in the district, up 132 percent since fiscal year 1990, adjusted for inflation; Wisconsin’s spending has grown the most, up 531 percent (see charts below).

Still, corrections are a relatively small fraction of total state expenditures. Wisconsin, Montana and South Dakota now spend a bit over 3 percent of their total state budgets on corrections, while North Dakota and Minnesota spend about 2 percent. Where these trends will go over the next few years is hard to predict.

Whatever happens with corrections spending, police and court budgets are strained nationally, according to Chris Uggen, professor of criminology at the University of Minnesota. In Hennepin County or Minneapolis, for instance, absorbing a significant funding cut would be difficult. “To the extent that there was any fat in the budget, it was trimmed several years ago,” Uggen said. Police and prosecutors are typically protected in the budget process in the name of public safety, but “often that means that we’re laying off their administrative staff so they’re spending time doing paperwork.” If a recession forces further cutbacks, he concluded, “you do reach a tipping point at which it becomes difficult to maintain the sort of crime control service level that we’re accustomed to.”

Cracks in the wisdom

Even if there are no cutbacks in public safety budgets, many believe that a deteriorating economy is certain to spur a rise in crime. But many scholars in the field—and a few police officers as well—tend to be more cautious. Yes, budgets will tighten, but public safety won’t necessarily be threatened, according to some. And while desperate times may encourage desperate acts, crime rates are influenced by a wide range of factors unrelated to macroeconomic trends.

Does economics play a part in explaining crime rates? “Clearly it does,” said Uggen. “But it’s complex.” He pointed to historical data on arrests and unemployment and noted that “there’s not a clear one-to-one relationship. In many times of economic expansion, crime rates have risen, and during times of contraction they’ve sometimes fallen.”

At the individual or group level, he said, the relationship is clearer. Uggen has studied recidivism among released prisoners and found that if they have steady jobs, they’re less likely to commit crimes. Also, overall economic conditions make a real difference in youth perceptions of whether to invest in school or consider illegal activities instead.

But such tendencies don’t necessarily add up to general societal trends, according to Uggen. “The relationship between economic conditions and crime is complex and crime-specific. There are some crimes—for example, residential burglary—where having more people at home during the day actually can help reduce some of those crimes.”

University of Montana criminologist Dan Doyle agrees that particular crimes, even violent crimes, can be associated with economic difficulties. “Domestic violence can go up when times are hard just because the level of tension within families and communities rises,” he said. But Doyle is cautious about linking crime rates and economic trends. “For many years, there’s been hypothesized a relationship between good times versus bad times and crime rates,” he noted, “and there have been a number of longitudinal studies where they’ve tried to correlate some sort of measure of economic health and some measures of crime. It’s proven to be difficult to draw really close correlations.”

Why is the conventional wisdom so hard to confirm? “When you find changes over time in any kind of social factor,” said Doyle, “they tend to be associated with so many other kinds of changes that it’s hard to attribute them to [just one factor], like crime being affected by economic circumstances.”

Uggen agreed. “Crime rates,” he said, “are much like rates of economic performance in that you’ll have a local phenomenon and you’ll make attributions as to its causes, but then you look around, and there are these larger secular trends in operation that are clearly multifaceted and systemic.”

And indeed, not all police are convinced that recessions cause crime. “We don’t tend to see that type of relationship,“ noted Angeli, of Marquette, Mich. “We do see a relationship between economics and crime, but not necessarily bad economic times. In other words, less fortunate or poorer people tend to be involved in more crimes than the wealthy. But when it comes to the economic times, I can’t say that I see a huge difference here.”

John Sweeney, chief deputy sheriff of Oneida County, Wis., says the recession hasn't hit his area's tourism-heavy local economy too hard yet, as far as he can tell. On the other hand, the largest manufacturing employer in Rhinelander, a paper mill, is now on rolling layoffs. In any case, he isn't ready to predict that the recession will cause a spike in crime. “I’m not gonna make that connection yet.”

And though many fear the effects of cutbacks in local police budgets, some officers say the public needn't fear desperate criminals roaming the streets emboldened by the absence of police. “We’ve gone through this before, and we’ve weathered the storm pretty good,” said Jesse Garcia, a sergeant with the Minneapolis Police Department. “Basically, we’ve tightened our belts and made ourselves a little bit more efficient. We already have a framework for that. If it happens again, we’ll do the same thing.”

Theory and data

Economists have studied the interrelationships between crime and economics for centuries, but the first formal model was set forth by University of Chicago economist Gary Becker in 1968. Becker described a theory of crime that assumed criminals were rational people who supply crime just as any businessperson supplies a service or product—with an informed calculation of costs and benefits.

For a criminal, the benefit of crime is, of course, the “ill-gotten gain”—the television, auto, cash or identity he or she manages to steal. The cost includes not just the crowbar used to pry open the window, but the likelihood of being caught and the severity of punishment if caught. There's also the opportunity cost to be considered; perhaps an hour spent as a pickpocket would be less lucrative than an hour delivering pizza. Rational criminals, in Becker's theory, will supply crime up to the point where costs outweigh benefits.

On the other side: society trying to minimize expected losses from criminal activity. Those losses, Becker explains in a June 2002 Region interview, include “ the damage done by the crime … [and also] the cost of policing, cost of taking somebody to trial, cost of punishment” and so on. Society won't pay for an officer on every street corner to prevent illegal parking—the cost would outweigh the benefit. Becker suggested that society will tolerate (or “demand”) a certain level of crime, and that demand is derived indirectly from the cost of crime protection. The higher the cost of protection, the less protection society will purchase, and the more crime it will tolerate.

Becker's model quickly sparked an outpouring of debate among economists, sociologists and other scholars. (It was also responsible, in part, for Becker receiving the 1992 Nobel Prize for economics, for “having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behavior.”) Was crime truly a rational act? Were criminals so calculating? Didn't punishment serve other purposes besides mere deterrence: revenge, for example? Becker's theory addressed many of these issues, but also invited elaboration and refinement.

For example, Becker’s model was essentially static. The calculation of how much crime to supply (or prevent) was described as a one-time decision based on present values. Later, economists would build dynamic crime models in which decisions made in the current period would depend not only on present cost/benefit calculations but also on earlier actions taken by the potential criminal or on the expected impact of current actions on future outcomes. Economists have also explored the intricate interaction between labor and crime policies, including recent models that show how labor market policies such as wage subsidies might affect crime rates and how crime policies such as jail sentences could influence labor markets.

An empirical explosion

But the main explosion generated by Becker’s theory was empirical research into its validity and implications. How well does deterrence work? For instance, does the threat of capital punishment result in fewer murders? Is the severity of punishment more or less important than its probability? Do improved labor markets result in less crime because they raise the opportunity cost of criminal activity? Do economic variables such as unemployment rates have greater explanatory power than deterrence variables like expenditures on corrections or policing?

Research on these questions should, ideally, examine data at the level of the individual, since Becker’s theory speaks to motivations of individuals. But for practical reasons (including the fact that few criminals are amenable to scientific inquiry and that random sampling requires large study populations) most research has looked at data aggregated at the state, regional or national level. Looking at data at this level, though, may obscure some of the effects Becker’s model predicts.

For example, while most studies have found that, as theory (and intuition) predicts, unemployment rates are positively associated with crime rates, the effect is surprisingly small, smaller than one would think when hypothesizing motives about “desperate” out-of-work individuals committing crimes to feed their families. As Harvard economist Richard Freeman wrote, “Even the largest estimated effects of unemployment rates on crime are much too small to explain the variation in crime. … Joblessness is not the overwhelming determinant of crime that many analysts and the public … expected it to be.”

Freeman and other economists suggest that, to some extent, this is because crime and employment aren’t mutually exclusive—indeed, some crimes (embezzlement, for example) are dependent on being employed—and the boundary between the two is porous. And while unemployment rates may not have a strong impact, recent empirical research indicates that higher wages for unskilled workers may result in less criminal activity, suggesting that opportunity cost is part of the equation for those contemplating crime.

Does deterrence work?

Economists have also devoted much attention to measuring the effect of deterrence—police, prisons and other direct costs—on crime. This research has looked at imprisonment rates, length of prison sentences and numbers of police, but the results have sometimes been hard to interpret. For instance, studies have often found that crime rates actually tend to be positively correlated with numbers of police—an inversion of the deterrence hypothesis.

Upon reflection, the reason seems clear: As crime rises in a given city, state or nation, politicians respond to public concern by hiring more police to stop the rise in crime. For similar reasons, imprisonment rates are often positively correlated with crime (not negatively, as deterrence theory predicts) because higher levels of crime increase political pressure to throw criminals in jail. So while Becker’s theory may well be valid—most individuals are no doubt dissuaded from crime by fear of arrest and punishment—other effects may obscure the true impact unless analysts employ careful statistical techniques to isolate the specific effect of a particular variable.

For example, one study—by Freakonomics co-author Steven Levitt—used the timing of mayoral and gubernatorial elections as a variable in estimating the impact of police numbers on crime rates. Increases in police force numbers, Levitt showed, were disproportionately concentrated in election years for these city and state officials, rising an average of 2 percent for a sample of 59 large U.S. cities versus 0 percent in nonelection years.

By taking this influence into account, Levitt was able to measure the independent impact of police numbers on crime rates. He found it to be large for violent crime, smaller for property crime. “Given the imprecision of the estimates,” however, he couldn’t conclude that the benefits of less crime outweighed the costs of hiring more police. A similar recent effort by economists at the University of California, Berkeley, used statistical methods to isolate the impact of imprisonment on U.S. crime rates and concluded that while the impact was significant in the 1980s, “recent increases in incarceration have generated much less bang-per-buck in terms of crime reduction.”

“Economists know little”?

Despite the plethora of carefully done empirical studies on crime and economics, it’s hard to reach definitive conclusions. And surprisingly, despite the massive amount of work done over the past four decades to verify and measure the economic theory of crime, many in the field are rather pessimistic about the current state of knowledge.

A 2008 paper by Harvard economists titled “What Do Economists Know About Crime?” surveyed the academic literature, studied correlations between crime rates and a variety of hypothesized determinants of crime over a long time period and across several countries, and presented a regression analysis to measure the individual influence of variables like per capita income, education levels, police per capita, arrest rates and incarceration. They found little evidence of solid causal relationships between these variables and crime and argued, therefore, “that economists know little about the empirically relevant determinants of crime.”

Similarly, economist Philip Cook at Duke University recently examined the course of crime rates in urban areas of the United States in recent decades and concluded that “the statistical evidence presented here indicates that [the 1990s crime rate] decline, like the crime surge that preceded it, has been largely uncorrelated with changes in socioeconomic conditions.”

Others, like University of Missouri-St. Louis sociologist Richard Rosenfeld, future president of the American Society of Criminology, continue to hold that macroeconomic conditions do indeed have a strong influence on crime rates. “Crime rates are likely to increase as the economy sours,” Rosenfeld wrote in a Los Angeles Times opinion piece in March 2008, which warned Angelenos “to brace themselves for more crime to come.”

But other scholars, including political scientist James Q. Wilson, former chair of the White House Task Force on Crime, are less certain. Almost a year after Rosenfeld predicted a rise in L.A. crime, Wilson wrote an editorial for the Los Angeles Times, noting that during 2008, crime had fallen in the city “at a time when the economy was reeling and unemployment was rising.”

Sometimes, Wilson noted, rising crime seems tied to a declining economy, as during the 1990s, but during the 1960s, when the economy was prospering, crime rates soared. “I wish we fully understood why,” he wrote. As chair of the National Academy of Sciences Committee on Law and Justice, Wilson hopes to sort out the complex relationships among crime, the economy and other factors. It is, he observed, “an effort to explain something that no one has yet explained: Why do crime rates change?”