Ready for a pop quiz? Good. Draw clear financial lines between easy credit, normal credit and a credit crunch.

Take your time … (cue Jeopardy! game-show music) … What's the matter, did junior steal your pencil?

In the midst of recession, and coming off an extended period of free-flowing credit, the nation and Ninth District are now grappling with a credit pendulum swinging hard the other way. In the process, the way people think about credit, as well as their access to and use of credit, are all getting a fresh audit. And for many, it's not pretty.

Consumers, businesses and even governments use credit—loans, lines of credit, credit cards and other forms of short- and long-term debt—to pay for things they either need or want now that they cannot buy outright with existing resources. In the past decade or so, use of credit has exploded, probably so much so that people have learned to take credit for granted. Whether it be to buy a new car or pay for college, or to meet payroll or expand office space, or to simply finance the sundry expenses of everyday life, people have come to assume that the necessary credit for such things is only a John Hancock away.

The past three months have been a stark reminder of the importance and fragility of credit. But credit markets were twitchy well before this. When the subprime mortgage industry started souring in the summer of 2007, financial markets began whispering of a “credit crunch,” or the lack of available credit for firms and individuals that sought it. With a steady flow of bad economic news since then, particularly in the banking sector, the term “credit crunch” entered the public vernacular over the course of 2008.

Never mind that there wasn’t a lot of evidence that a credit crunch was actually taking place through the first nine months of the year. If the notion of a credit crunch is any time borrowing is not exceedingly easy and cheap, then, yes, there was a credit crunch. But poor lending standards—including credit that was priced too cheaply for the underlying risk—are what led to much of today's financial and economic troubles. So it's useful to think of a credit crunch in stricter terms: Whether banks and other firms have the capacity and willingness to extend credit to customers who are both seeking it and capable of paying it back at rates that accurately reflect borrower risk.

Through the first nine months of 2008, credit in various forms was still widely available, but interest rates were rising for a lot of borrowers—consumers, businesses, government—and standards for getting credit were rising. In other words, borrowers had to pay a little more for credit than they were accustomed to, and poorly rated users were paying rates that were higher still, or they were not getting credit at all. Some might call that a credit crunch. Others simply call it a prudent risk model.

But when financial markets became stressed in mid-September, there was evidence for the first time of significant and broad credit tightening. Those that had resources to lend were fearful of extending credit; those that did lend often demanded significant premiums for doing so.

Major pieces of the credit market that grease the broader financial system—interbank lending, commercial paper, municipal bonds and asset-backed bonds that provide liquidity to finance consumer purchases like homes and cars—tightened considerably. Even now, credit liquidity in certain areas of the financial market continues to flow like room-temperature molasses: You can coax it out, but you’ve got to be diligent and patient.

Anecdotes of tighter credit conditions and their negative ripple effects are easy to find these days. In October, GE Money, the consumer finance arm of General Electric, told major businesses in the Ninth District, including Marvin Windows and Polaris Industries, that it was tightening credit standards. In Michigan, Gov. Jennifer Granholm announced in November that the state was pushing $150 million into that state’s banks and credit unions in hopes of loosening credit. Capital-intensive growth industries like wind energy, which has been growing like gangbusters in the district, are spinning into the headwinds of tighter credit markets. As borrowing costs rise, some projects are being delayed temporarily, others mothballed indefinitely.

But measuring the vital signs of credit markets is more complex than taking an anecdotal pulse from different parts of the patient. Certainly, credit conditions have changed dramatically. Yet despite the perception and fear of frozen credit markets, business is still getting done, even in the midst of a recession. People can still be seen going in and out of banks, and seemingly not just to turn in the keys to a foreclosed home.

Recent research from the Federal Reserve Banks of Minneapolis and Boston highlights the fact that it’s hard to define and identify a credit crunch with certainty. Aggregate data suggest that credit is not nearly as tight, or as frozen, as generally believed; but the aggregate data also hide a lot of nuance suggestive of a credit crunch.

Complicating matters is the fact that the financial world was dumped on its head in September, but in the time-lag sphere of detailed macro data, the world is still mostly upright. It’s a bit like reading the Cliff Notes to a novel. You know how the story ends, but you have to read the book for critical details of how the plot unfolds. And in the current case, the data book is still being written.

For these reasons, and given the importance of the matter to the Ninth District economy, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and the fedgazette conducted four polls from late October through mid-November to investigate general credit market conditions for financial institutions and businesses in the district. (Two polls were part of regularly scheduled annual polls, and two were special polls conducted specifically for this credit project. See description and methodology.)

Cumulatively, the surveys show that financial institutions in the district are not short of capital to lend. But credit volumes have nonetheless shrunk over the past three months because lending standards have risen, while loan requests and the quality of credit applicants have fallen substantially over this period.

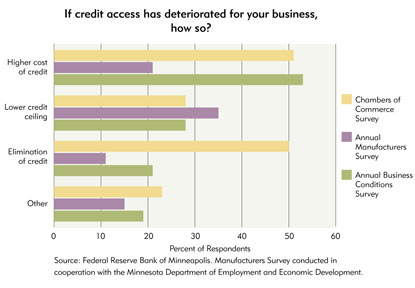

From the business side of the credit table, many firms have seen their access to credit deteriorate over the past three months. For those affected, less access has generally meant higher costs and lower ceilings for credit, which in turn have affected firms’ plans for capital expenditures and hiring.

Whether spliced according to geography or economic sector or business size, credit conditions appear fairly uniform across the district, with two notable exceptions. Large financial institutions demonstrated tighter credit conditions than the group as a whole; and among district states, credit conditions in the Dakotas were less taut than for the district as a whole.

This might seem like a tidy and contained explanation of credit conditions. Better to call it generalized and sanitized. According to extensive open comments gleaned from the surveys, many respondents fretted over credit tightening, and financial markets might well be overlooking good credit risks. Financial institutions, for their part, complain about mixed messages—being pushed by one arm of government to lend and pulled by another to be more conservative. Given the easy-credit path that has led to this economic point in time, it appears that financial institutions, businesses, consumers and government will need some time to figure out what the new “right-sized” credit environment looks and acts like.

Get your credit here

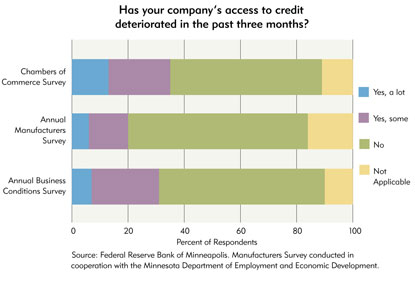

The evolving credit story can be told from several angles. Without question, some firms and individuals are having more difficulty obtaining credit. For example, three separate surveys of Ninth District businesses found that between 20 percent and 35 percent of firms (depending on the poll) saw deteriorated access to credit from financial institutions over the previous three months (see Chart 1).

Chart 1

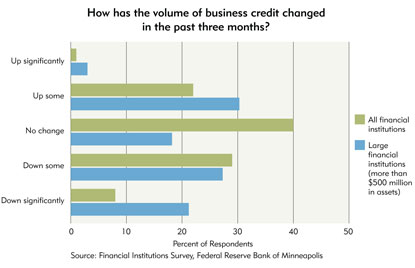

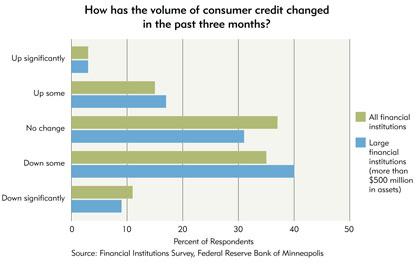

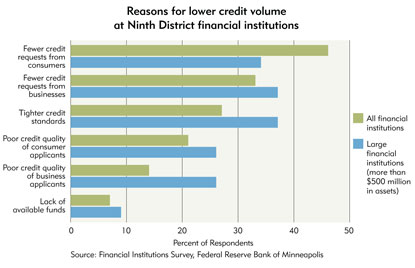

A fourth survey of banks and credit unions in the district found that credit volume to businesses and consumers dropped as well over the same period (see Charts 2 and 3).

Chart 2

Chart 3

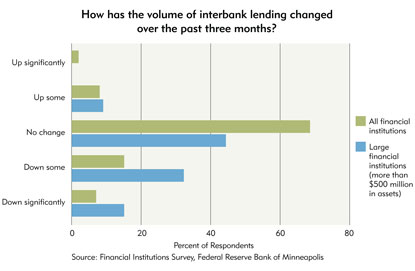

Financial institutions also lend to one another, and the decline of such activity (also known as interbank lending) has been the subject of considerable angst at the national level and a stated target for much of the federal government’s emergency bailout package. How much these efforts have helped unglue interbank lending is hard to say exactly, in part because it’s impossible to know what would have happened had nothing been done.

But the fedgazette survey of financial institutions found that interbank lending saw a clear, though small, net decline among respondents; 22 percent said such borrowing was down over the past three months, while 10 percent saw an increase. Among large financial institutions (over $500 million in assets), the survey was more telling: Close to half (47 percent) said interbank borrowing had declined, and only 9 percent said it had risen (see Chart 4).

Chart 4

Some banks and credit unions volunteered that they had been summarily cut off from borrowing from other (usually larger) institutions. A Minnesota financial institution with $75 million in assets said a fed funds borrowing line in place at US Bank for three decades was “dropped with no notification,” as was a borrowing arrangement with Wells Fargo. A Wisconsin bank with $700 million in assets said correspondent borrowing lines through JPMorgan Chase and M&I Bank were either reduced or eliminated.

This triumvirate of results—tighter access to credit for firms, and lower credit volume and interbank lending among financial institutions—is enough for some to scream “credit crunch” in a crowded bank. But it’s more complicated than that.

One important criterion for a credit crunch is a lack of money, and few district financial institutions said they have that problem. Only 7 percent of bank and credit union respondents said the lower credit volume was due to a lack of lendable funds. Large institutions were only slightly more likely (9 percent) to have this problem.

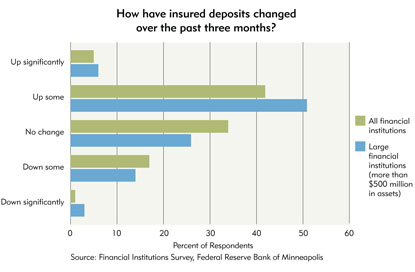

In terms of having lendable funds, banks and credit unions appear to have made up for the decline in interbank loan activity through an increase in insured deposits. Forty-seven percent of financial institutions reported higher levels of insured deposits just in the past three months. On the flip side, only 18 percent of respondents said insured deposits were lower (see Chart 5).

Chart 5

That net increase is most likely from people pulling money out of the stock market and elsewhere and putting it in the local bank or credit union. A Minnesota bank with $46 million in assets noted that deposits have been on the upswing as core customers “bring more of their funds to us. … We have plenty of money to lend.”

But even for those financial institutions that are flush with cash (and especially for those that are not), credit is no longer being hurried out the door with every application. That’s how much of the credit market operated in the past, and it is the source of many of today’s financial difficulties. And as the old saying goes, when you find yourself in a hole and want to get out, step one is to stop digging.

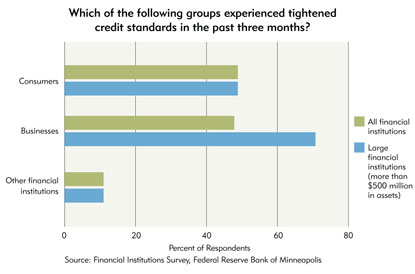

Financial institutions have put down the proverbial shovel by raising their credit standards to make sure that past credit mistakes aren’t repeated. Roughly half of financial institutions said that credit standards had been raised for both consumers and businesses. However, rising credit standards for businesses were much more prevalent among larger institutions (see Chart 6).

Chart 6

Said a South Dakota bank with $500 million in assets, “Credit has not stopped, but no credit will be allowed outside of policy limits and standards. … There is less tolerance for risk in this kind of market.”

Tighter credit standards are manifested in many forms. An owner of a small business services firm in Minnesota said that credit “is taking longer to get than usual, more documentation is needed … more of a down payment is needed, and my credit hasn’t changed.”

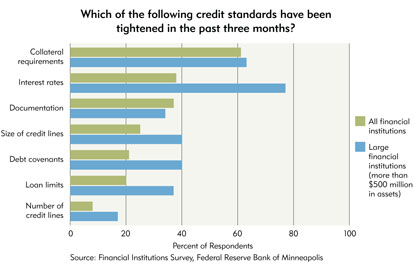

Financial institutions said that raised credit standards most often mean higher collateral requirements, documentation and interest rates. However, 77 percent of large banks said they have raised their interest rates on credit, a rate considerably higher than at small- and medium-sized institutions (see Chart 7). Firms also cited higher cost of credit as the most common form of credit tightening (see Chart 8).

Chart 7

Chart 8

By definition, higher standards make it more arduous to get credit, which is pushing some potential economic activity to the back burner. A pharmaceuticals firm with $30 million in revenues and 45 employees said, “The banks we deal with have significantly tightened standards and made it more difficult to expand a very profitable enterprise, risking the creation of 100 new jobs in our company over the next year.”

A Minnesota plastics manufacturer with over $20 million in sales saw a proposed $5 million manufacturing facility get canceled “until credit opens back up,” a company official said. The firm had a 15-year relationship with its bank, and attempts with two other banks “couldn’t get past the loan committee.” The failure to obtain credit means the company will not be able to grow into the medical market as planned, and shelving the project will keep the company from realizing $3 million in new revenue for 2009 at a time when “existing sales have started to decline.”

Firms and consumers having difficulty finding credit at their usual financial institution are looking elsewhere, particularly if they possess good credit. Though such an approach didn’t help the Minnesota plastics manufacturer, there is anecdotal and survey evidence to suggest more are doing it and finding some success. For example, though credit volume for businesses was down for 40 percent of medium and 48 percent of large financial institutions, business credit volume actually rose for about one-third of them as well.

One small Minnesota bank commented, “We’re seeing more loan requests from applicants who are customers of another financial institution that has evidently tightened their credit standards.” A Wisconsin retail business with $50 million in sales and 115 employees noted, “Our bank is asking far more questions and taking much longer making decisions. We are talking to more banks to get what we need.”

Got credit? Never mind

The other tricky part of labeling the current environment a credit crunch is differentiating between the lack of supply and the lack of demand. While there are some liquidity issues, the downturn in credit volume is also the simple result of lagging demand from businesses and consumers over the past three months (see Chart 9). Said a Minnesota bank with $174 million in assets, and echoed by other financial institutions, “We have money to lend. We need good applicants.

Chart 9

The drop in credit demand has been highest among consumers. A North Dakota bank with $450 million in assets noted that “the consumer is very vulnerable. They have a lot of debt and they have no margin for error. If they lose their job or if their business is impacted, they go immediately into default.”

There are lots of potential reasons why credit-seeking is down. Borrowers might be scared away by higher credit cost or feel that they will not qualify because of the higher standards. Then there’s the little matter of an economic recession, which is not conducive to deal-making. According to a small financial advisory firm in Minnesota, “People are scared to make investments, scared to take risk and scared to make purchases.”

A Montana financial institution with $300 million in assets commented, “We have money to lend, but customers aren’t asking for the most part. They are concerned about what the future holds economically. … Many of our business customers are working on ways to hunker down to hang on through this period.”

That’s also the case for a construction materials firm doing about $6 million in business annually in the Dakotas and Montana. According to a company official, the uncertainty and volatility in the industry convinced the firm’s directors to step away from several potential acquisitions “and has put future expansion projects on hold until they have a better idea of what will happen with the economy.”

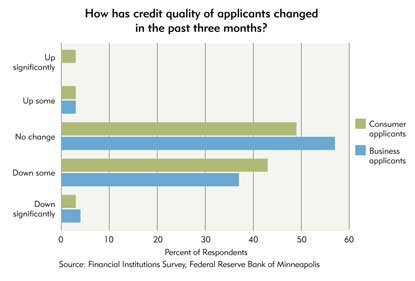

Making matters worse, for those who do seek credit, fewer are qualified to receive it. Better than 40 percent of financial institutions said credit quality of both business and consumer applicants had declined over the past three months (see Chart 10).

Chart 10

Nonbank extra credit

Banks and credit unions aren’t the only places offering credit to businesses. A lot of credit is also distributed by nonbank firms—they extend it to consumers and business clients, and they similarly receive credit from other firms they do business with.

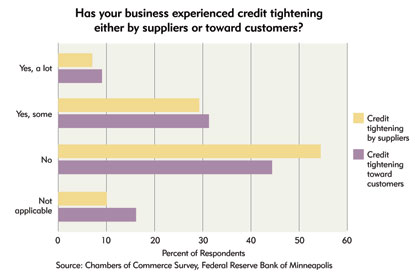

Among business respondents to the special poll of chamber of commerce members, 40 percent said they had tightened credit on customers, and almost one in 10 had tightened a lot. In turn, 36 percent said that suppliers had tightened credit on them (see Chart 11).

Chart 11

Tighter credit comes most often in the form of shorter repayment periods; this was particularly cited when suppliers tightened credit. This tactic contrasts with the strategy of higher interest rates among financial institutions. It appears that firms are worried not about how much extra money they might earn on late accounts; they are worried about getting paid at all, as cash flow has become king.

A Minnesota marketing firm with $5 million in sales and 45 employees said that its clients “are paying slower and spending less because they are holding cash and using us as a lender.” A small Minnesota technology consultant with $500,000 in revenues said it was also receiving payments from clients “much later than typical, which is negatively impacting our cash flow and reducing our ability to pay our suppliers on time.”

A manufacturer with operations in the district and $80 million in worldwide sales reported that it was in a “very good financial position” and was sitting on strong future orders. Nonetheless, a company official said, “we are being very diligent with collections, and our suppliers are treating us the same.”

Apple and orange splices

The four surveys conducted by the Minneapolis Fed also offer a snapshot of credit conditions broken down by variables such as firm size, sector and state. Though a wide variation in credit conditions might be expected given today’s volatility, survey results don’t show a lot of differences. Instead, broad credit trends tend to hold in subgroups, varying only by a matter of degree.

For example, among firms reporting poorer access to credit, a much higher percentage of large firms—79 percent of large firms by revenue, 71 percent by employment—said they were paying higher costs for credit compared with small- and medium-sized firms, at about 50 percent.

Among economic sectors, construction firms were more likely to say they had seen their access to bank credit deteriorate than firms in any other sector. Construction firms were also more likely to report tighter credit both toward their customers and by their suppliers, and to say tighter credit had negatively affected hiring, capital expenditures and company expansion. Given the downturn in housing and in the overall economy, the difficulties in the construction sector are hardly a surprise. Still, it was not a runaway loser in the credit race; other sectors ran fairly close behind, virtually across the credit board.

Though each state in the Ninth District offered some unique variation, broad credit themes also held across states. The most notable difference: Credit conditions reported by firms were looser in the Dakotas, most likely the spillover effect of strong farm income for several years running, as well as a booming oil sector in North Dakota.

Similarly, financial institutions in the Dakotas reported that credit volume and applicant quality (both firms and consumers) fell by less over the previous three months compared with other district states. In fact, North Dakota was the only state where more lenders reported rising (rather than falling) credit volume.

Freeze frame

So what do all of these survey results mean? For starters, results from these four unique surveys tend to reinforce broad conclusions about national or district credit conditions from other sources, including the general findings from the Federal Reserve Board’s most recent survey of senior loan officers back in October.

But determining the existence of a credit crunch, and its severity if one does exist, with any exactness is difficult, because there are many qualitative decisions that aggregate data do not reflect. For example, many banks appear to have ample cash on hand. As a result, the availability of lendable funds does not generally seem to be a problem. With anecdotes starting to pile up about credit denials, higher loan costs or lower credit ceilings, financial institutions can appear to be hoarding cash rather than pushing it out the door and into the economy.

But given the volatility of the economy today, it’s virtually impossible to know when Goldilocks-like credit standards have been achieved—not so tight that they squelch market activity and not so loose that they encourage more reckless borrowing. Numerous banks pointed out that federal and other policymakers have exacerbated credit vertigo. Congressional members and other government officials have been urging banks—particularly those that have received infusions of government capital—to lend freely. At the same time, regulators have been beseeching banks to distribute their capital judiciously.

A Minnesota financial institution with $600 million in assets wrote that “the regulatory environment has become much too aggressive. … The left hand is promoting liquidity in the markets and stabilization of the economy to encourage lending, while the regulatory side is becoming much tougher (and) reactive.” A Montana community bank with $135 million in assets agreed. “Treasury says on the news that it is encouraging banks to lend and work with its borrowers, but (examiners) are doing exactly the opposite.”

So the notion of a credit crunch—or worse, a “freeze”—might be an inaccurate label because it broad-brushes credit markets that are multi-layered, complex and dynamic. Without doubt, various portions of credit supply and demand are struggling to come together. But especially at the local level, and in the Ninth District, many banks are lending, and firms and consumers are borrowing. When it comes to financial services, the district looks more Main Street than Wall Street.

However, a new credit environment is evolving; banks and credit unions are more cautious about whom they lend to, and fewer borrowers are seeking new credit in the first place. Good credit risks might have to look harder than they did a few years ago for financing and pay more for it. In general, financial markets might be described as returning to traditional standards, where credit history, down payments and metrics such as loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios matter again.

Eventually markets will reach equilibrium, but probably not until after a prolonged feeling-out period where all players—consumers, firms, lenders, government—help define the new-normal credit market. Here, available money is not the issue, but rather information, and confidence—in the future, and in the parties to any credit transaction.

Said one official with a local chamber of commerce in Minnesota, “Fear is the greatest problem right now. Business and banks are indicating that they have money to lend, but businesses are afraid of the future.”

Credit Surveys Data [xls]

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.