Bankruptcy filings tend to rise in hard economic times: When workers lose their jobs or their hours are cut, they have more difficulty paying their bills. When you consider that the nation is in the midst of the worst recession in recent memory, you might bet that more households are filing for protection from creditors.

And you'd be right. Nationwide and across the Ninth District, the number of personal bankruptcy filings jumped in 2008, according to statistics from U.S. bankruptcy courts. Preliminary numbers also suggest that filings increased at an even faster rate in the first few months of this year.

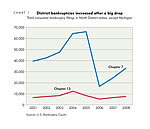

But bankruptcy levels are still far below levels seen in the first half of this decade, and particularly in 2004 and 2005 (see Chart 1). In Minnesota, for example, bankruptcies last year were still about one-third lower than in 2005. The gap is even more pronounced in North Dakota. Bankruptcy filings there rose by 14 percent in 2008, but were still 62 percent lower than their peak earlier in the decade.

Ninth District or bust

Part of the reason for these surprising numbers is timing: Bankruptcies haven't increased as dramatically as might be expected because they tend to lag the economy. It takes time for economic turmoil to affect sufficient numbers of households to drive up bankruptcy numbers. This delayed effect can be seen following the 2001 and 1991 recessions, when filings were higher in recovery years than during the downturns.

But a bigger source of the long-run trend is the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005. That act, intended to prevent perceived abuse of bankruptcy laws, made it more difficult and costly for individuals to seek debt relief. It also set off a mad dash among those on the financial edge to take the plunge before less favorable legal conditions were in place. So while the new law cut the number of bankruptcy filings once in place in October 2005, it was the underlying cause of the mid-decade run-up in filings.

"There was a fear of what the new law was going to bring," said Gregory Duhl, a professor at William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul who teaches bankruptcy law. "It was fear of the obstacles that might come once the law was changed."

Personal bankruptcies reached more than 2 million nationally in 2005, an unprecedented increase of 30 percent over the previous year. There was a concomitant deep drop in 2006 because many people who otherwise might have waited to file did so earlier.

Since then personal bankruptcies have risen, though the increases vary among district states. In 2008, filings increased in Minnesota and Wisconsin at a pace similar to that for the nation as a whole (see Chart 2). However, rates have increased less in the western three district states. In South Dakota, which has one of the lowest rates of bankruptcy filings (by population) in the nation, 2008 filings increased just 8 percent.

Differences in state rules don't play much of a role in the differing bankruptcy rates among states, since bankruptcies are handled in federal courts. The disparity is probably based on economic conditions: Bankruptcy, for example, is closely tied to employment, and jobless rates are much higher in Minnesota and Wisconsin than in the Dakotas and Montana. (For more information on the recession's effects by state, see "Recession in Perspective")

The recession also appears to be leaning harder on household solvency in all district states. Preliminary bankruptcy figures for the first quarter of 2009 show that filings are continuing to rise. In South Dakota, for example, first quarter filings were up 23 percent over the same period a year earlier.

A new chapter begins

Despite the rise, bankruptcy levels are still well below peak levels earlier this decade—even in the midst of a recession dating back to late 2007. This suggests that the 2005 reform law has had a considerable impact on the decision to file for bankruptcy. The intent was to cut perceived abuse of the bankruptcy system, primarily by those taking advantage of Chapter 7.

Individuals can seek three classes of bankruptcy protection. Under Chapter 13, filers get temporary relief from bill collectors in exchange for setting up a plan to pay off their debts eventually. Chapter 11 is the least-used option for individuals; it is primarily used by businesses and high-income earners to financially reorganize. In a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, individuals who are completely insolvent liquidate what assets they have to pay off what debts they can, and the rest of their debt is written off. This option is mostly used by lower-income earners, and a means test determines who can take advantage of it.

One of the primary goals of the 2005 legislation was to get more people to file Chapter 13 rather than Chapter 7. This goal was based on the premise that many people who could manage their finances in a Chapter 13 filing were nonetheless opting for Chapter 7. The law has also pushed the cost of bankruptcy higher by imposing higher filing fees for all chapters, requiring financial management classes for all filers, requiring greater documentation and imposing stricter means tests for Chapter 7, which pushes up legal costs.

The new rules eventually had a major effect on the incentives to file for bankruptcy. Some believe the law has had the intended effect of discouraging bankruptcy as an easy way out for shaky-but-still-solvent debtors. But not everyone agrees. Some say the new law just made it hard, period, to file for bankruptcy. "There may be more people who would like to file now who simply can't afford to do so" given the higher costs under the 2005 law, Duhl said. As evidence, court data show little shift to Chapter 13 bankruptcy, as originally envisioned under the new law.

So it's worth asking what, if anything, changed about those who file for bankruptcy. Research published late last year in the American Bankruptcy Law Journal took a detailed look at the characteristics of bankruptcy filers in 2007, compared with similar data sets from 2001, 1991 and 1981.

One consistent finding over time was that—as might be expected—a large share of filers had low incomes, and many had recently experienced some financially stressful emergency, such as job loss, medical or legal troubles, or the death of an income-earner in the household. One difference in the 2007 data was that post-reform filers were in worse financial shape on average than filers in other years and had been enduring their financial hardship longer than people who went bankrupt before the law changed.

These findings might help explain both the stagnant trend in Chapter 13 filings in district states and the rising trend in Chapter 7 filings: For many filers, it seems, the new law might postpone the actual filing, but it has not eliminated the need for financial relief. So many will file, eventually, and when they do, they are still much more likely to do so under Chapter 7.

These findings also suggest that the number of bankruptcy filings in the district can be expected to rise in the near future, even after the recession ends. If people are waiting longer to come to terms with their financial problems because of tighter bankruptcy rules, many of those currently in trouble will go broke further down the road.

Bernie McCarthy, clerk of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Helena, Mont., thinks more may be yet to come. "If we see an increase as a result of the economic downturn, I don't expect to see it for another year," he said.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.