Sales were sputtering last fall at Ken Vance Automotive in Eau Claire, Wis. Overall sales at the company's two dealerships declined 25 percent in September and October 2008 compared with the same period in 2007. On slow days, salespeople hit the phones in an effort to entice former customers into the showroom to kick the tires on new and used Buicks, Cadillacs, Hondas and Volkswagens. Only brisker business in parts and service kept the firm's General Motors-Hyundai operation in the black.

President Ken Vance blames the tough economy for most of the drop in vehicle sales, but he said that "the credit picture has obviously had a great bearing" on depressed sales at his dealerships.

The credit picture—the availability of auto financing—is anything but clear, and decidedly cloudy for some people who would like to buy a car. Many lenders have tightened their standards, especially for people with spotty credit histories. For customers with marginal credit, Vance said, "the odds were better a year ago than they are today" of securing an auto loan on terms that they could live with.

Slumping sales that worsened in the wake of the financial crisis—light vehicle sales in the United States fell 32 percent in October from the same month in 2007—are causing great distress in the automotive industry. GM and Chrysler have been pushed to the brink of bankruptcy, and auto dealers in the Ninth District and across the country are struggling for survival. In Minnesota, dealers shed 2,000 jobs in October, according to state employment figures.

Whether, and to what extent, tighter credit has contributed to the slump is the subject of intense debate by district auto dealers, manufacturers, lenders and other industry stakeholders. Are willing buyers walking out of dealerships because credit has become too expensive, the terms demanded by lenders too stringent?

Certainly the auto finance industry has become more averse to risk than it was a few years ago, when buyers with shaky credit could get seven-year loans with minimal money down. Auto credit markets were tightening even before the onset of the banking crisis in mid-September, thanks to rising default rates, the travails of domestic auto manufacturers and difficulties selling subprime auto debt to investors. Fewer auto loans were being written, and the share of new loans going to people with prime credit was increasing.

Lenders appear to have further tightened their purse strings since September. Concern that tight credit is stifling auto purchases and other consumer spending was the impetus for a Federal Reserve program announced in November to lend up to $200 billion to the holders of securities backed by consumer debt, including auto loans.

All of which doesn't mean that district consumers can't buy a new set of wheels today. For buyers with reasonably good credit, loans with good terms are still available from banks and the finance arms of many auto manufacturers. Even low-income, subprime borrowers may be able to secure financing from credit unions, which haven't appreciably tightened their credit standards and are expanding their auto lending.

Credit obstacle course

A collective shiver ran through the auto industry in October when GMAC Financial Services, the country's biggest auto lender, announced that it was taking a more conservative approach to auto financing. Henceforth, car buyers would have to score 700 or above on FICO (Fair Isaac Corp.'s yardstick of credit worth), put more money down and pay off the loan in less time. The changes—on top of higher interest rates introduced early in 2008—put GM vehicles and other autos financed through GMAC out of reach for millions of Americans with less than prime credit.

Sales of GM vehicles were already trending downward at Vance Automotive, but after GMAC's move, they plunged 32 percent in October compared with the previous October. Along with "unrealistic" interest rates, Vance said GMAC is "completely out of sight on the quality of the buyer, and the restrictions that they are throwing up." Soon after the new rules went into effect, a long-time customer with excellent credit walked away from a sale when GMAC demanded a 20 percent down payment on a used car.

GMAC's credit crackdown is only one of the most dramatic and recent examples of tautening auto credit. Many other auto lenders have been pulling in their horns for a year or more, lending less and paying much more attention to credit quality than in the past. Auto finance as a whole has become more conservative because of fallout from the subprime housing debacle and subsequent economic downturn, said Tom Libby, an analyst with J.D. Power and Associates, a national marketing research firm focusing on the auto industry. "Everybody has tightened up," he said.

Despite a large drop in the prime interest rate in 2008, the finance arms of the Big Three U.S. automakers raised their interest rates last fall. According to the Federal Reserve, the average annual interest rate for new loans financed by the subsidiaries, or "captives," of domestic auto lenders (a group that includes Ford Motor Credit and Chrysler Financial) was 6.2 percent in September. That's more than a percentage point higher than the rate in the third quarter of 2007.

The Fed data also show an increase in the average down payment required by the captives. The typical loan in September was for 85 percent of the vehicle's value—a sharp drop from 95 percent in July and well below the average loan-to-value ratio in this decade.

In addition to this general reeling in of credit by U.S. automakers, all three domestic captives cut back on low-interest incentive financing last year, and GMAC and Chrysler Financial retreated from the auto lease business.

No money down, no car!

A new caution in auto lending extends beyond the Big Three finance companies to banks and independent auto finance firms. JPMorgan Chase and AmeriCredit, a nationwide auto finance company, have reduced their auto lending and tightened their credit standards in the past year or so. Chase Auto Finance, the country's largest bank-owned auto financer, is demanding higher down payments and capping subprime loans at five years.

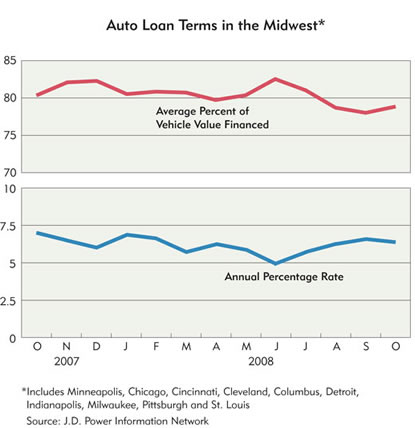

J.D. Power auto lending data show a broad tightening of credit standards in 2008 for a broad swath of the Midwest that includes Minneapolis-St. Paul and parts of district states Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. Average auto-loan interest rates in the region declined year over year in October—the opposite of the Big Three trend. But the average down payment increased to over 21 percent of the purchase price (see chart).

Small, independent banks in the district don't do much auto lending, and historically they have concentrated on serving existing customers with prime credit. But these banks appear to be following the lead of big banks in lending more conservatively. Bill Underriner, the owner of an auto dealership in Billings, Mont., noted that one local bank hiked its interest rates in October. "Don't worry, I was over there talking to them about it," he said.

In Minnesota, community banks have not appreciably tightened their standards for prime borrowers, said Marshall MacKay, CEO of Independent Community Bankers of Minnesota, which represents about 250 small banks in the state. But he added that local bankers have even less appetite for subprime, stand-alone auto loans than they had six months or a year ago.

Banks have also joined the captives in driving a hard bargain on commercial loans used for "floor planning," or dealer inventory. Restricted financing has left dealerships scrambling to buy vehicles to sell, said Scott Lambert, executive vice president of the Minnesota Auto Dealers Association (MADA). "The dealers are having a hard time getting credit on reasonable terms, and that is as big a problem as consumer credit right now," he said.

Keeping it loose

Timidity isn't universal in auto lending. Ford Motor Credit and the finance arms of foreign auto manufacturers haven't significantly raised their credit standards in the past year. These firms are financially healthier and have higher credit ratings—and therefore lower borrowing costs—than Chrysler and GMAC. Ford Credit spokesperson Meredith Libbey said that the firm began shedding risky loans in 2002, and so has seen no need to restrict credit further. "We have not tightened our standards; we've got good criteria and we're sticking by them."

Likewise, there's scant evidence of tightening at Toyota Motor Credit Corp. and Nissan Motors' finance subsidiary. Both firms launched zero-percent financing campaigns in October in a bid to wrest more market share from their Detroit-based rivals.

Another bright spot for borrowers is credit unions, which are aggressively pursuing auto lending. According to the Credit Union National Association, 31 percent of credit union loans nationwide are for autos, and in the first nine months of last year outstanding credit union loans for used vehicles (which accounted for more than half of auto lending) increased almost 6 percent. Flush with deposits and not weighed down by toxic mortgages, credit unions are disposed to lend, said Steven Rick, the association's senior economist. "Credit unions haven't tightened up their lending standards as much as their competitors, like the banks and captive finance companies," he said.

Interlakes Federal Credit Union in Madison, S.D., doubled its auto lending last year as its growing membership took out loans on new and used cars at interest rates 1.5 percent to 2 percent lower than the prevailing rate offered by area banks. General Manager Lynnette Taylor said that in most instances a FICO score of 650—50 points less than GMAC's cutoff for financing—qualifies borrowers for a five-year loan covering 90 percent of the vehicle's purchase price.

Nevertheless, the overarching trend in auto lending, both nationwide and in the district, is a migration from risk toward safety. Prime credit is desirable; anything less is to be handled gingerly, if at all.

One reason for this change is climbing delinquency rates. A recent report on automotive lending by Experian PLC, a multinational credit bureau, showed that in the second quarter of 2008 the number of loans 60 days past due was 11 percent higher nationwide than in the same quarter in 2007. District states have much lower rates of auto delinquency than the country as a whole, but Experian data suggest that auto delinquencies have also been creeping up in the region (detailed state statistics were unavailable).

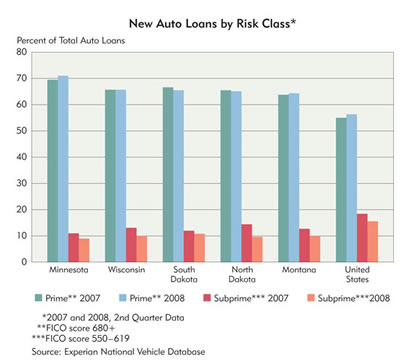

The rise in delinquencies coincides with a shift in the quality ratio of new auto loans. Nationwide and in the district, lenders wrote more prime loans and fewer subprime loans in the second quarter of 2008 than they did the previous year, according to the Experian report. The subprime share declined nationally and in every district state (see chart).

More recent Experian data were unavailable at press time, but it's probable that this flight to quality has accelerated since the banking crisis hit in September, hastened by the fragile finances of many lenders and problems selling subprime loan contracts in money markets leery of securitized consumer debt.

Waiting for the thaw

So if you're pining for that new- (or used-) car smell, chances are the credit bar has been raised since you last set foot in a district showroom. Consumers with prime credit can buy the vehicle they want at a good price, because many dealerships are desperate to bring in revenue. However, depending on the lender and the borrower's FICO score, the loan contract may come with strings attached—a bigger down payment, a shorter loan term—than was customary for prime borrowers a year ago.

Drivers with less than sterling credit can still buy a vehicle, but they're likely to pay a lot more up front and face higher monthly payments on shorter loans. "People with spotty credit records are going to have a harder time at least getting prime credit," said Lambert of MADA. "They may be paying more for their loan." For buyers with bad credit—a FICO score of 400 or lower—there's always the bus. As of November most auto lenders were rejecting those loans.

Consumer confidence will undoubtedly return when the national economy regains its footing, reviving the sagging fortunes of auto dealers in the district. The weekend after the presidential election, sales picked up at Ken Vance Automotive—a sign to the owner of rebounding consumer optimism following months of uncertainty about the direction of federal policy.

But dealers must be able to extend credit to their customers if they are to capitalize on pent-up demand for automobiles. No one knows whether the progressive tightening of auto credit that has occurred over the past year or two is temporary, or the beginning of a prolonged period of more conservative lending.

If major lenders continue to restrict credit, that could spell trouble for auto dealers in the district, leading to consolidation and higher prices because of reduced competition. In some district states the ranks of dealers have been thinning for a while. According to MADA, more than 60 dealerships have closed their doors in Minnesota over the past five years.

Just before Thanksgiving, six Denny Hecker Automotive dealerships shut down in the Twin Cities, resulting in 400 layoffs. Owner Denny Hecker attributed the closing to a "perfect storm" of financial misfortunes, including Chrysler Financial's decision to cut off his credit lines in October.