When Chad Wilkerson, an economist and vice president at the Oklahoma City branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, would go out to give talks about the current economy, he would frequently be asked about the downturn in the housing market. Often, Wilkerson was asked how the falloff in residential markets, which was obviously a nationwide phenomenon, was playing out in rural areas. How bad were housing markets in rural areas? Are rural markets the same as urban markets? Are all rural markets the same?

The problem for Wilkerson is that he had no data to help him answer those questions. He had some pretty good hunches, based on his expertise and his understanding of rural economies, but even an educated guess is still a guess. So Wilkerson set out to gather available data and then develop a method to analyze and present that data to help people in rural areas better understand their position.

The results were published in the Kansas City Fed's Main Street Economist. The fedgazette talked with Wilkerson about his findings and about how rural areas in the Ninth District are faring in this housing market.

But first, some clarification: Rural housing in the following interview refers to nonmetro housing, and it's based on a new measure by the Federal Housing Finance Authority for nonmetro home values by state. Wilkerson and his colleagues aggregated those numbers by census region and then for the whole country. It was only in early 2008 that such data first became available. These data refer to entire nonmetro areas of states, so they can include everything from towns that abut metro-area counties to those that are hundreds of miles from a metro area.

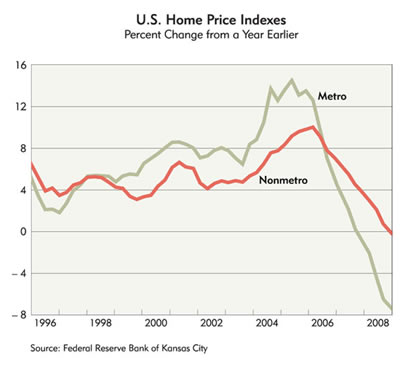

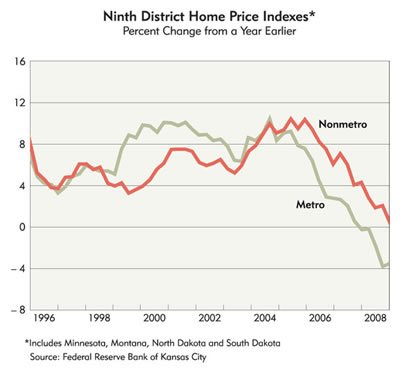

fedgazette: One of your key findings is that rural home values have

performed well relative to urban values during this housing downturn

[see charts below], so there is some good news in housing markets.

Wilkerson: There is good news in the nonmetro data, but there is also some evidence of possible downside risk, especially when you compare the housing data with things like per capita income growth—things that home prices should track pretty closely with in the long run.

fedgazette: I'd like to get back to that in a minute, but first let's talk about broader trends. Are rural housing prices stronger than urban across the board, or are there pockets where markets are markedly better or worse?

Wilkerson: Rural prices have held up better than metro prices in all parts of the country. That said, in some parts of the country, rural prices have fallen, specifically in the Pacific census region, where prices have fallen about 4 percent from the peak. But that compares with declines of about 20 percent in metro areas, and that's really the only rural census region where prices have fallen more than 1 percent. In all other rural areas of the country, prices are essentially flat or, in some parts of the country like the West South Central, fairly strong. The West South Central has experienced the highest home price gains of any area in the country since early 2007—metro or nonmetro. The rest of the Southern rural areas have experienced decent gains.

The Mountain areas of the country and the West North Central, which would include much of the Ninth District, have also experienced decent rural home price gains. Essentially, in the census regions that include most of the Minneapolis and Kansas City districts, along with parts of the Chicago district, prices in metro areas were down 3 percent from the beginning of 2007 through the third quarter of 2008, while rural prices were up about 3 percent.

fedgazette: What story are you telling to explain that price difference?

Wilkerson: I think that story begins with looking at why home prices in urban areas rose more than in rural areas in the first half of this decade, and there are largely two reasons, one of which involves the restrictions on land use, or land availability. The biggest price gains in metro areas have generally come on the coasts or in metro areas with land use restrictions. The other explanation, and I'm careful about this because I don't have great data, is perhaps tighter underwriting standards in rural areas than in metro areas. And that conclusion is driven largely by the home price-to-income ratio. In all census regions, home prices outpaced incomes by a wider margin in metro areas than in rural areas.

fedgazette: What about population growth rates? Were metro areas growing faster during this time, and would that explain part of this phenomenon?

Wilkerson: That's a good question. Population did grow much faster in metro areas than in rural areas earlier this decade, likely providing a more rapid increase in demand for housing in cities, where initial supply may have been more limited, due in part to the land constraints we discussed. And this could have pushed up metro home prices faster for a while. However, the faster metro population growth was probably not a surprise to builders or lenders, since it was a continuation of a longer-term trend. So it was likely taken into account to some degree on decisions about when and where to build houses.

fedgazette: So let's talk a little bit more about the issue of home prices relative to incomes. How should we think about this correlation?

Wilkerson: Well, we want to be careful. I stressed that in my article, and I will stress that again here. In metro areas across the country, home price growth was greater—much greater—relative to income growth than it was in rural areas. I don't have a complete answer for why that is, but it was the case everywhere.

fedgazette: And, of course, by lending standards you are referring in part to the exotic loan packages offered by many lenders. These data then suggest that such loans weren't made in rural areas, or at least to the degree they were offered in urban areas.

Wilkerson: That's right; but it's only a suggestion from the data, which are incomplete. So what I'm basing my analysis on is, again, the degree to which home prices relative to income were more out of line in urban areas, even in interior parts of the country where land restriction is much less of a factor.

For the nation as a whole, metro area home prices grew 3.2 times faster than per capita income from 2000 to 2005, which is roughly the boom period in home prices. In rural areas that number was 1.8. In both cases, that's a big contrast to the previous five-year period, when in no part of the country—whether rural or metro—did home prices increase more than 1.2 times (or 20 percent) faster than incomes. Again, that may connect back to what was going on in credit markets, but that is only a circumstantial connection within these data.

fedgazette: As you note in your article, the bust in urban home home prices was coincident with a boom in commodity prices. To what degree have commodity prices kept rural home prices strong? Given the recent drop in many commodities prices, should we expect rural areas to take more of a residential real estate hit?

Wilkerson: It is definitely a risk going forward. The increase in commodities prices, along with perhaps better underwriting and better price fundamentals, have certainly buoyed rural home values for the last couple of years. But this isn't the only risk facing rural home markets. As we discussed, rural home prices grew 1.8 times, or 80 percent, faster than per capita income in rural areas from 2000 to 2005, and while that's not as fast as urban markets, it is still considerably higher than the previous five years and could be worrisome. But I don't think that most rural areas need to fear the kind of home price decreases that urban areas have experienced.

fedgazette: Are there any factors that would cause you to paint a gloomier picture for rural areas? For example, in urban areas, the decrease in home building and other home-related expenditures seems to be a large driver in the current slump. How might rural areas fare in this regard?

Wilkerson: I think that is a concern, but we have to remember that new home construction slowed much more quickly in rural areas, even though home price fundamentals were in better shape in rural areas. That means that there are likely much lower inventories of unsold homes in rural areas. So when a housing rebound occurs—and I don't have a better forecast on that question than anyone else—rural areas should be in better shape to have an earlier rebound because their inventories are likely lower.

Now, the wild card, as always, with rural areas is their difference from urban economies, largely based on the agriculture and energy sectors. And, as you know, that certainly holds in the Ninth District.

fedgazette: Thank you.

—David Fettig

Read the report: Is Rural America Facing a Home Price Bust?

Main Street Economist,

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.