“We’re moving toward a French Revolution.”

But the only heads rolling in this one will be heads of lettuce, according to Terry Nennich, a University of Minnesota regional extension educator in Crookston, who compared the surge in U.S. farmers markets to long-established markets in France.

But the only heads rolling in this one will be heads of lettuce, according to Terry Nennich, a University of Minnesota regional extension educator in Crookston, who compared the surge in U.S. farmers markets to long-established markets in France.

Farmers markets are not particularly new in the United States. Ever since farmers could haul their products into town on the back of a buggy, local markets have been a staple in many communities. However, they slowly declined in popularity as modern-day agriculture and grocery retail replaced a fairly narrow selection of local food with a much wider array of products from other sources.

Now, farmers markets are returning en masse to feed consumers’ desire for locally grown products. The reason for this growth is pretty simple: Both consumers and producers see the benefits. Consumers perceive better value and nutrition in locally grown food, and also feel more secure knowing the source of their food. For producers, local markets offer an additional revenue source and create opportunities for small-scale farmers to translate a hobby or part-time endeavor into earned income.

Lettuce count the markets

Farmers markets are flourishing across the country. There are hundreds of farmers markets in the Ninth District alone, from tiny unincorporated Engadine in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula through the Twin Cities and to western Montana and points between.

The growth in farmers markets is “astonishing,” said Joanne Berkenkamp, program director for local foods at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP), a research and advocacy group in Minneapolis. “People are looking for authenticity in their food choices.” Given the increasing occurrences of salmonella and E. coli scares, “it matters to people to know where their food comes from,” she added.

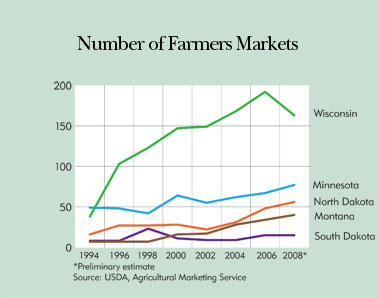

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), every district state has witnessed significant growth over the past decade and a half (see chart), though the total number in South Dakota is still marginal, at 15. The largest share of overall growth in the district actually came in the latter half of the 1990s, when the number of farmers markets more than doubled to an estimated 266. That growth rate has since moderated, but another 85 have been added as of spring this year.

Wisconsin is easily the district leader in total markets at more than 160. For its population, North Dakota also has a large number of markets. Stephanie Sinner, marketing specialist, North Dakota Department of Agriculture, attributes that growth to the strong support provided through the state-run North Dakota Farmers Market and Growers Association, adding that “farmers markets are also popular with North Dakotans, probably because of their dedication to all things North Dakota.”

Some state sources indicate even stronger growth in farmers markets than USDA estimates. For example, the state-sponsored Minnesota Grown directory counted 10 more farmers markets in that state than the USDA’s tally (77 in 2008), while a Minnesota Farmers’ Market Association member suggested there are well over 100 farmers markets currently operating in the state. A Wisconsin spokesperson estimated that about 230 markets were selling produce in 2007, or about 40 more than USDA estimates for that year, and about 70 more than estimates for 2008.

The size of these markets varies as well. In Montana, for example, markets range in size from seven vendors in Glasgow to Bozeman’s 200. Several district cities have more than one market location: The downtown St. Paul market operates 15 satellites in city neighborhoods and suburban communities. In La Crosse, Wis., shoppers can visit three market locations three days a week from May/June to October. Markets in Bismarck, N.D., are open on alternating days three times a week at two locations, with a third location another day.

We're not talking small potatoes

Farmers markets conjure pictures of brightly colored vegetables artfully arranged on tables in the town park or on a main street. But markets don’t just happen; they take serious planning and support to be successful for vendors and the community.

For example, the Farmers’ Market Manual for Minnesota—itself a three-pound product developed by the University of Minnesota Extension Service—addresses everything a community market needs to be successful. That includes nonproduction kinds of issues that market organizers and vendors typically lack experience in—from the legalities of operating a market to helping vendors price their products—that can ultimately doom farmers markets, say market experts.

One of those experts is Larry Lev, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at Oregon State University. At the spring annual meeting of the Minnesota Farmers Market Association, Lev said that the incredible growth of markets veils the fact that “a surprising percentage of them fail.” He noted that paid staff, a set of bylaws, and attention to location, vendor characteristics and potential buyers’ needs are all necessary for a successful market. Markets too often fail when they’re operated on a shoestring by volunteers, who see them as a feel-good community activity rather than as a business endeavor. Vendors also need to be serious about displaying and marketing their products to draw buyers.

Other sources added that a successful market depends on matching buyer needs with vendor products, which can be a challenging balance when Mother Nature dictates what gets grown when, and where. But a persistent imbalance leads to a failed market.

Lev also emphasized the importance of community partnerships, such as working with chambers of commerce and local government agencies to provide financial support, volunteers and help with logistics. He added that it’s important to measure market attendance to demonstrate the economic ripple effect on the community. Counting attendance also helps vendors estimate potential sales, Lev said.

Although markets often attempt to measure consumer spending, it’s a hit-and-miss effort for the most part, as consumers don’t keep an exact accounting of their purchases and farmers working on a cash basis don’t always keep good records either.

Without a paper trail on revenues and costs, and with little experience in setting retail prices, farmers might be short-changing themselves. “[Vendors] may have premium products but don’t often price as such,” said Robert Weyrich, value-added specialist in the South Dakota Department of Agriculture.

That’s good for consumers, but probably only in the short term, because vendors might discontinue their efforts at a farmers market—maybe unnecessarily—if they are underpricing their goods and leaving potential (but unreaped) profits on the table.

Quick learners

Regardless of the challenges, farmers new and experienced are flocking to farmers markets because they offer a new revenue stream.

While data on farmers market vendors aren’t abundant, it’s clear that vendors come in all sizes and with various financial goals; some sell exclusively at markets, while (most) others use such sales as secondary income.

The profit opportunity of selling directly to consumers is obvious. “If you sell at a market, you get 100 percent of retail,” said Minnesota’s Nennich, who is also a grower and farmers market vendor. “If you sell to a store, you lose 30 percent to 50 percent, and if you sell to a distributor, you lose 50 percent to 70 percent.”

DruMontri, associate manager of the Michigan Farmers Market Association, said Michigan’s markets support about 3,000 farmers and vendors statewide. Of those, only about 50 use the markets as a primary source of income. Others are community gardeners, retired people and part-time farmers, she said.

It’s hard to say whether that’s representative. According to preliminary data from a 2006 USDA survey of farmers markets, 25 percent of responding market managers reported that their vendors relied on the market as their sole source of farm-based income. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s their only income. Many vendors are not traditional, full-time farmers looking for a little slush money; rather, many vendors use these markets to scratch a back-to-the-soil farming itch.

IATP’s Berkenkamp said she’s seeing opportunities for farmers who want to grow on a small scale and mid-career people who want to take up farming. Some are looking to invest in organic or sustainable farming, she said. But she is also seeing more immigrant farmers, women farmers and a growing number of college graduates in their 20s. “The face of farming is changing,” Berkenkamp said.

The USDA also reported an increase in small farms (those 10 to 49 acres), from about 531,000 in 1997 to nearly 564,000 in 2002, the most recent year for which data are available. The increase is likely the result of multiple factors, including strong demand for “farmlet” housing near urban areas, but also the growth in small-scale farming.

A little something for the effort

Revenues at farmers markets can be tough to gauge because many are small and many vendors work on a cash basis.

But some estimates exist. Total sales value of farmers markets reached about $1 billion in 2005 (the most recent year available) compared with $888 million in 2000, according to the Agricultural Marketing Service. That amount has certainly increased since then, given the overall growth in markets. Though revenue growth lags the growth of new market locations, a USDA source attributed this to the preponderance of newer and smaller markets.

Estimates at the state and local level are similarly sketchy. Angelyn DeYoung, marketing officer for the Montana Department of Agriculture, said that 18 farmers markets around the state (about half of the USDA’s estimated number for Montana) reported nearly $1.4 million in sales in 2007.

Some markets have attempted to gauge consumer spending in an effort to better understand demand. A 2005 survey of attendees at the 97-year-old Duluth, Minn., farmers market, where Saturday attendance ran from 500 to 900, found that 40 percent of shoppers spent between $20 and $50 per visit, and another 46 percent spent between $10 and $20.

Jim Lucas, Michigan State University Chippewa County extension director, conducted a survey at the Sault Ste. Marie market the week after Labor Day last year that showed over 400 people spending $10 to $12 per person. It’s hard to say how the 40 or so vendors fared individually, but not many are likely living exclusively off such endeavors.

We need more heirloom tomato vendors

The strong surge in farmers markets has also led to some growing pains for both the supply and demand side of the corn row. In many cases, supply is not keeping up with strong consumer demand for locally grown food. At the National Farmers Market Summit held last November, the lead issue was “growing” more farmers.

But not all markets suffer equally from this problem; some markets have vendors on a waiting list, while others go begging. Perhaps this imbalance is an indication of the success of farmers markets. Vendors can afford to be a little picky in some areas and select the market that will bring in the greatest profits. Ditto for markets: A successful one can afford to be persnickety about vendors.

Ruth Hilfiker, University of Wisconsin Extension commercial horticulture educator for St. Croix and Pierce counties, noted that some markets in her area don’t have enough vendors, losing out to those markets that have proven successful, like River Falls, which has a waiting list of vendors.

According to Jack Gerten, manager of the St. Paul market, that market currently has about 154 downtown vendors, but about 50 growers are on a waiting list. St. Paul’s cousin market in Madison, Wis., is even larger: The Madison market on the Capitol Square is limited to 300 vendors—and about 300 more are in line should a space open up, according to Larry Johnson, Dane County farmers market manager. While attendance continues to grow at both markets, each is constrained by limited physical space.

Cornucopia, overflowing

Some organizers are recognizing the spillover benefits of farmers markets. For example, many towns see the weekly farmers market as an economic development tool to draw people back to Main Street businesses.

In 2003 the Dane County farmers market surveyed people shopping on 29 market Saturdays that season and determined that consumers spent nearly $6 million at downtown merchants, said Johnson. His market draws an average of 20,000 people “on a good Saturday.” Roughly translated, that works out to $10 to $15 per attendee spent through the course of the summer in downtown shops outside of the market.

The Sault Ste. Marie market operates on Wednesday nights and captures people attending concerts in a nearby park. Both events led to downtown shops staying open late, said the U.P.’s Lucas.

Many markets are located in the parking lots of local businesses, often supermarkets or garden centers, that see the lure of the fresh produce as a way to get customers into their own stores. A Pamida store in Bemidji, Minn., hosts the town’s farmers market in its parking lot.

“The farmers market brings traffic to our store, and our traffic shops at the market,” said Jim Naasz, Pamida’s manager. While Naasz couldn’t put a number on the increased business, his store’s experience is positive enough that Pamida stores elsewhere in Minnesota are looking for similar partnerships. “We can share customers, and that’s beneficial to both of us,” Naasz said.

And new growing technologies, such as high tunnels, hoop houses and hydroponics, allow producers to extend their seasons. For example, an Engadine, Mich., market vendor raises kale and spinach in hoop houses to offer the product beyond the regular growing season. And a vendor at the six-year-old winter market in Madison, Wis., uses the same technology to sell spinach in December.

Madison is just one city extending its market season beyond fall into, and sometimes through, the winter. While winter markets are not universal, they are increasing in numbers and vendors. An extended growing season offers fresh produce later in the year, and vendors of other products, like jams, cheeses, meats, and Christmas trees and decorations, keep the markets viable and popular. Rochester, Minn., for example, has had a winter market for two years, two Saturdays a month through mid-April.

As markets develop and spread, many are also looking at better and broader marketing campaigns. In Montana, the state’s farmers market organization is partnering with Travel Montana to put a map of farmers markets on the tourism Web site as “a way for visitors to sample Montana and taste the local flavors,” said DeYoung.