Success is sweet, but James Prudent is betting that the reverse is also true. Centrose, the Madison, Wis., startup that he heads, plans to use sugars to enhance the potency of existing drugs, including a treatment for lung cancer. The company's core technology for attaching sugar molecules to drug compounds was developed by a pharmacy professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and licensed from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF), the university's tech transfer agency. "Our concept of enhancing drugs with novel sugars has immense market potential," Prudent said. "The challenge now is to pick the right drugs and move them through the development pipeline."

Earlier this year, Centrose raised $1.3 million in private equity to fund further development of sugar-based drugs, and Prudent believes that the firm can attract more investment and grow in Madison, a burgeoning center for medical technology.

Directors of university tech transfer offices (TTOs) dream of startups like Centrose.

They're seen as a vital part of the tech transfer mission, even more important than licensing in general when it comes to stimulating local and regional economic development. Startups are powerful engines of economic transformation because they tend to stay in the communities where they were born, increasing their payrolls and tax contributions as they prosper. And in high-tech regional "clusters" such as Madison and the Twin Cities (a hotbed for medical devices), one thriving startup often leads to the birth of another that in turn begets its own spin-offs.

Licensing startups is also appealing to universities because of the possibility of a big payday if a company hits the commercial jackpot. As a condition of licensing, many universities, including UW-Madison and the University of Minnesota in the district, acquire equity in new companies—a stake worth potentially tens of millions of dollars if a new firm subsequently goes public or is taken over by another company.

"The problem with startups of course is that they're extremely high-risk," said R. Timothy Mulcahy, vice president for research at the U of M. "Less than one in 10 ultimately gets acquired or goes to an IPO [initial public offering]. But they represent such a great opportunity that everyone's pushing for them."

Enthusiasm for startups has led tech transfer offices at research universities in the district to put considerable effort into licensing inventions to new, preferably local technology firms. WARF draws from a $10 million Venture Fund to provide seed capital to promising startups, sometimes in tandem with venture capital firms. In the U of M's Venture Center, a recently expanded off-campus facility focused on licensing startups, former CEOs looking for their next venture help fledgling companies write business plans, build management teams and pursue funding from private investors. Montana State University (MSU) in Bozeman works closely with TechRanch, a local nonprofit organization that assists high-tech firms, to launch its licensed startups.

The benefits that these activities bestow on universities and their communities are questionable, however. A headcount of startups that have come out of district research universities over the past decade shows that TTOs have had limited success in creating new companies through technology licensing. And the inherent risks of investing resources in embryonic enterprises cast doubt on business formation as a tech transfer strategy.

Few are chosen

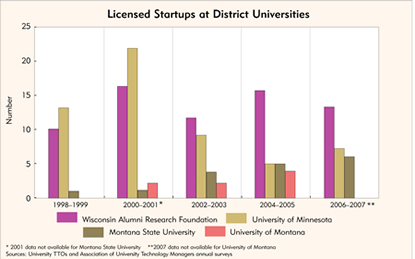

Every year WARF executes dozens of licenses based on hundreds of discoveries disclosed by UW-Madison faculty, students and staff. Typically, all that inventiveness and paperwork yields a handful of licensed startups. Centrose was one of six new companies to take out a WARF license last year; over the past five years, the organization has averaged seven startups annually—roughly one for every $130 million in research expenditures. Other district universities have produced fewer licensed startups (see chart). The U of M launched four in 2007 and has averaged three a year since 2003, as has MSU. North Dakota State University (NDSU) in Fargo has licensed no startups in the past decade.

These numbers are on par with the startup performance of TTOs across the country. Just a few institutions, among them the University of California System and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, regularly achieve double digits in annual licensed startups. Most U.S. universities launch fewer than 10 annually.

So relative to their peers, district universities seem to be doing an effective job of creating new enterprises crucial to the economic well-being of their home states and communities. But a different picture emerges when the statistical lens widens to include companies that start life in the region without a university technology license.

Compared with the number of businesses started annually in the region by entrepreneurs outside universities, the birthrate of university-licensed firms is negligible. In Minnesota, for example, over 28,000 new businesses registered with the secretary of state's office last year. About 4,500 new companies were established in North Dakota. Many high-tech jobs pay higher wages than positions in retail, food service or tourism. Still, the relative rarity of university-licensed startups means that their effect on regional economies is minimal.

The number of startups that owe their existence to university licensing also amounts to a fraction of the number of firms that trace their origins to a district research university. Little comprehensive research has been done on businesses formed by faculty, staff or graduates of universities, but a 2004 report by the U of M's Institute of Technology suggests that university licensing is just the tip of the iceberg. The study identified roughly 4,150 companies, including Medtronic and Cray Research, that IT alumni founded or co-founded. Two-thirds of the firms were operating in Minnesota, employing more than 175,000 people and generating approximately $46 billion in annual revenue.

Many of the firms in the IT survey were founded decades ago, before universities had the opportunity to license their discoveries in earnest. But the survey's findings are supported by anecdotal evidence, such as the number of unlicensed firms on the client rosters of university technology incubators.

Virtually every startup licensed by MSU goes through TechRanch, said Gary Bloomer, the organization's client development director. But those firms make up only about 40 percent of TechRanch clients linked to MSU (typically half the total assisted each year). The rest are unlicensed and connected with the university in another way—headed by a former professor or student, or advised by a faculty member on the board.

Likewise, NDSU's futility in launching startups means that no licensees reside in the university's year-old, $7.5 million Business & Technology Incubator. However, two of the seven current tenants were founded by NDSU graduates.

Risk and reward

Every TTO in the region can cite a success story—a startup that blossomed into a major employer or earned shareholders (including its parent university) a handsome return when it went public or was acquired by another company.

WARF hit a home run with TomoTherapy, a 10-year-old Madison firm that developed a radiation therapy system for the treatment of a wide variety of cancers. The licensed technology has generated millions of dollars in royalties, said WARF Managing Director Carl Gulbrandsen, and the organization's equity stake yielded millions more when TomoTherapy sold stock to the public last year. "That's been very good for us," Gulbrandsen said. The firm is profitable and currently employs about 660 people.

More recent WARF licensees that have made hopeful beginnings include Centrose and Cellular Dynamics International, another Madison company co-founded in 2005 by acclaimed UW-Madison stem cell researcher James Thomson. Both Centrose and Cellular Dynamics have received government grants in addition to private equity financing.

At the U of M there are signs that the Venture Center's hands-on approach to launching startups, intended to maximize long-term revenue potential, is working. Director Doug Johnson points to Orasi Medical, a 2007 startup that has developed a method of diagnosing Alzheimer's disease and other brain disorders, as a product of his strategy to focus on launching a few firms with a good chance of success.

"I would rather have us start one company a year that's another Medtronic than 25 failures," he said. Last fall, Twin Cities-based Orasi landed $2.4 million in private financing, including a contribution from Glen Nelson, former vice chairman of Medtronic.

Successful licensed startups have also emerged from MSU and South Dakota State University in Brookings. Ligocyte Pharmaceuticals, an MSU licensee partly owned by drug giant GlaxoSmithKline, has grown into a 47-employee firm over the past decade.

But for every TomoTherapy, Orasi and Ligocyte, there are many more university startups that never attract private capital, produce a viable product or turn a profit. As Mulcahy observed, less than 10 percent of university licensed startups—actually 8 percent, according to a 2002 analysis of data gathered by the Association of University Technology Managers—ever progress to an IPO. And going public doesn't ensure survival, or sustained commercial success.

The hard truth about university-licensed startups is that jump-starting a new business out of a campus lab is arduous and risky. "It's a little bit easier licensing technologies to the DuPonts of the world," said Bloomer of TechRanch. "Building a company around a university technology is difficult because oftentimes those technologies are developed without a market in mind, which is the exact opposite of how a traditional entrepreneur would go about starting a business."

Not only are university technologies usually raw and unfocused; their inventors are often more interested in conducting research than running a company, and they tend to be ignored by institutional and angel investors. "Most of the technologies that we evaluate are too early and too undeveloped for external investors because the risk of failure is too high," said Johnson of the U of M. Startups like Centrose and Cellular Dynamics that have attracted sizable private investment are the exceptions.

What would markets do?

These uncertainties and risks raise the question of whether universities should be spending public funds—or royalties earned from the licensing of publicly funded research—on cultivating startups.

Identifying promising technologies and guiding them along the tortuous path to market entails an investment that sometimes extends to direct financial aid for startups. In addition to funding the Venture Center, the U of M has set aside $1 million annually in licensing proceeds for grants and loans that inventors can use to further develop their discoveries and launch firms. Such support also exacts an opportunity cost; resources allocated to nurturing startups are not available for licensing technologies to existing firms, or for investments in education and basic research.

At what point should universities let the market decide which technologies should give rise to new companies and which ones should be licensed to established firms—or sent back to the drawing board? Markets have proven themselves more astute pickers of valuable technologies than government-supported institutions. Arguably, if entrepreneurs and investors outside a university don't take interest in an invention, it's probably not worth commercializing through a startup.

Michael Gorman, founding managing director of Split Rock Partners, a Twin Cities venture capital firm, believes that some university support for startups is appropriate. Tech transfer offices can serve as entrepreneurial catalysts, helping to recruit talented managers and providing seed capital to sustain a new firm until it can secure institutional funding.

But "one of the key questions is how is something like that managed, because the danger is for market forces not to be applied," Gorman said. Without input from business and financial experts outside university walls, internal politics and favoritism can influence decisions about which discoveries and startups receive university backing.

Given the limited impact of licensed startups on local and regional economies, and the risks of investing in untried technologies, the larger question for district universities is whether the home-run potential of such investments justifies the costs.