In many macroeconomic trends, there often lies a sleeper, some underlying cause or driver that plays an outsized role, at least in comparison to what the average layperson might know about it.

Concerning the rapid and steady rise in farmland values, that sleeper is an arcane tax law known as 1031 like-kind land exchanges. Though the language might sound like obscure bureaucratese, farmers and other landowners are fluent in it, and use of this tax law appears to have played a big role in pushing farmland values higher in the district, particularly in the first half of this decade.

A 1031 exchange allows a seller of business or investment property to defer any capital gains taxes on the sale of that property if the seller reinvests the gain in a different property within 180 days. Technically, the properties are supposed to be similar—farmland for farmland, for example—but in practice a much looser definition applies.

During the economic boom of the 1990s and the subsequent housing explosion this decade, hundreds of billions of dollars in capital gains were realized from real estate sales. Rather than pay federal capital gains taxes—15 percent today, but as high as 39 percent as recently as 2003—many property owners did what economists would expect: They took the economic incentive offered by the IRS and "did a 1031."

But in each case, sellers had a short six months to trade sideways, or risk having to pay the tax anyway. That meant billions of dollars were looking for a new home—or farm, as it were—and fast. With a deadline of 180 days, buyers have an economic incentive to pay whatever it takes to get the piece of land they want, so long as the marginal excess is less than the avoided capital gains tax. And in the merry-go-round of land speculation, when the market gets hot, you've only overpaid until the next sucker comes around and boosts everyone's land values.

Is that all you want?

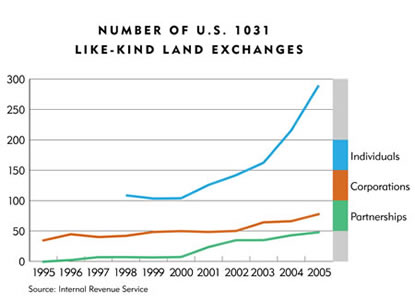

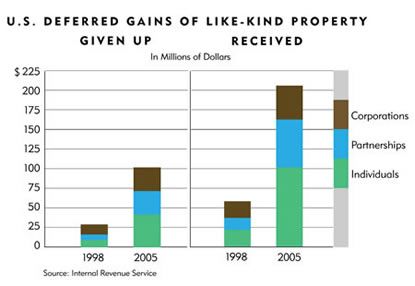

Surprisingly little data or research exist on 1031s. On request, the IRS supplied the fedgazette with 1031 activity and value data from 1995 to 2005. They show steeply rising growth of transactions and total value (see charts). However, the extent to which this trend involves farmland is not entirely clear.

IRS data do not distinguish between specific kinds of owners (farmers and nonfarmers, for example) or the types of property involved (residential, commercial and farmland, for example). The IRS data are broken out into three categories of firms—individual, partnership and corporation—all of which have seen strong growth. Each category likely includes (possibly many) farmland transactions, but how many is unknown.

Sources in real estate, farming and banking widely agreed that 1031s have been instrumental in the steady rise in farmland values, particularly in the first half of this decade. Kelly Cape, head of the Day County (S.D.) Farm Service Agency, said via e-mail that 1031s have "played a large role in the increased land value in our area." Such buyers often set the market price in that area and "probably added $100 to $200 an acre on a lot of sales."

Throughout South Dakota, demand for ag land is coming from out-of-state parties, many of whom travel to the state to hunt pheasant, deer and other game, according to Jodie Hickman, executive director of the South Dakota Cattlemen's Association. Often these buyers are selling higher-valued property in another state and using the 1031 law to purchase ag lands, killing two birds with one land purchase: grabbing a chunk of land to hunt permanently and saving themselves a sizable tax bill to boot.

In the Fairmont area of south-central Minnesota, escalating farmland values resulted from "a huge amount" of large tracts being bought by 1031 exchanges, according to Jerry Fast, an executive with Profinium Financial. Fast said via e-mail that farmland around the southern exurbs of the Twin Cities—places like New Prague, Shakopee and Belle Plaine—was selling for $10,000 or more per acre and for weaker producing land. "So they came down to our area and bought 2,000 acres at a crack with much higher productivity and higher farm rental value for one-third the price," Fast said.

Montana reportedly sees similar horse-trading of farmland between the two halves of the state: the more populous, scenic and higher-valued west, and everywhere else.

Many farmers and ranchers in western Montana are cashing in on a strong real estate market, "1031ing properties in eastern Montana that are not as expensive," said John Youngberg, vice president of governmental affairs for the Montana Farm Bureau, in an e-mail.

Youngberg didn't think that 1031s were playing a role in the initial transaction for the western farmland, but said they were a definite factor in operations relocating to eastern Montana. Ranches in desirable western locations—in mountains, along streams—are getting bought "for amounts far exceeding what they can expect in agricultural returns, [and] those ranchers are taking their money to eastern Montana," where they can outbid any of the locals, Youngberg said.

We're not talking about chump change in terms of the capital gains looking for shelter. According to Youngberg, one western ranch sold several years ago for around $2 million, and the same ranch sold last year for over $7 million. "I don't think that pricing of land has as much to do with commodity prices in Montana as [much as] the willingness of rich people to pay any amount for a ranch or farm," he said.

In the end, the average farmer or rancher is competing for land with either someone who has no need to earn a profit off the land or is a cash-flush farmer buying the next parcel as a tax write-off. That's why, despite a volatile cattle market over the past decade, median pastureland values in eastern Montana have risen from a little over $100 an acre in 1998 to about $350 last year, according to a year-end 2007 land survey report by Northwest Farm Credit Services. The survey attributed this to the fact that buyers can find properties with amenities similar to those in western Montana "at a fraction of the cost."

Not so hot no more

It appears that 2006 might have been a pivot point regarding the use of 1031s, at least according to numerous sources and some economic evidence. (IRS data for 2006 or later were not available because separate statistical studies on corporations, individuals and partnerships must be completed before the aggregate data can be released, according to an IRS official.)

About this time, the housing market was beginning its descent for a crash landing, and the resulting slowdown in real estate turnover, particularly around fast-growing metros, likely took some 1031 activity with it. Similarly, crop prices began rising in 2006 and farmers started earning stronger incomes. Multiple sources noted that farmers are no longer taking a back seat to 1031 flippers at land sales—unless, of course, the farmer is the one doing the 1031 exchange.

Two years ago, nonfarm investors typically made up half of all bidders at land auctions and were often the winning bidders, said Brent Qualey, a real estate broker and vice president of Botsford & Qualey Land Co. in Fargo, N.D. "They absolutely dominated the market." These days, he said, "we've definitely seen less 1031 buyers."

Another possible reason for the slowdown in 1031 activity is bureaucratic: The Treasury Inspector General of Tax Administration released a critical report last year on the matter, stating "there appears to be little IRS oversight" of 1031s. The agency, as well as some state tax offices, has reportedly promised to tighten oversight.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.