A few good nurses are hard to find in North Dakota these days. A report issued in 2006 by the Center for Rural Health at the University of North Dakota reported an 11 percent vacancy rate in statewide hospital positions for registered nurses, those with three or more years of training.

North Dakota isn't alone in reporting a dearth of RNs. In the late 1990s, health care facilities nationwide started to run into problems staffing specialized units, such as intensive care, and the problem has since spread to general health care. Hospitals and clinics have had trouble hiring all types of nurses, including licensed practical nurses (LPNs), but RNs are particularly scarce. Industry analysts say structural factors, primarily the aging of the U.S. population, are causing both a long-term rise in demand for nursing services and a decline in the nursing workforce.

North Dakota isn't alone in reporting a dearth of RNs. In the late 1990s, health care facilities nationwide started to run into problems staffing specialized units, such as intensive care, and the problem has since spread to general health care. Hospitals and clinics have had trouble hiring all types of nurses, including licensed practical nurses (LPNs), but RNs are particularly scarce. Industry analysts say structural factors, primarily the aging of the U.S. population, are causing both a long-term rise in demand for nursing services and a decline in the nursing workforce.

Is there really a nursing shortage, and if there is, how long will it last? A look at the data suggests that health care providers in some parts of the district are indeed struggling to fill their nursing rosters. And while the problem isn't as bad in other areas, the long-time prognosis calls for more recruiting pain.

In other industries, staffing difficulties can lead to longer wait times for customers and lower profits for owners. But a stretched nursing workforce is potentially a life-and-death issue; according to recent studies, nursing shortages can lower standards of care, increasing the incidence of medical complications and causing more patient deaths.

Nursing a shortage

State-level statistics on staffing trends in nursing are spotty, but the data that are available indicate that health care providers indeed are having trouble hiring nurses.

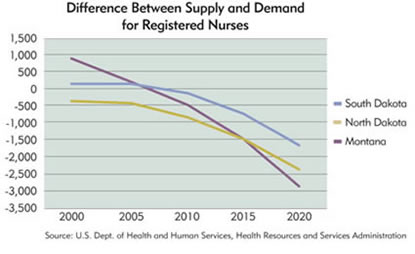

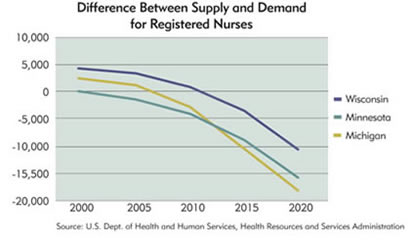

One of the best estimates of supply and demand for nurses comes from the Health Resources and Services Administration, an arm of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HRSA has developed a model of nursing supply and demand based on the characteristics of the nursing workforce and the overall population. This model generates current and future estimates of the supply of full-time equivalent RNs versus the number demanded by employers. The difference between supply and demand is the nursing surplus or shortage. The data are available for all 50 states.

The HRSA analysis shows that in 2000, the only district state with a nursing shortfall was North Dakota, with 400 fewer nurses than the market demanded. By 2005 (HRSA produces estimates every five years), the hiring gap had widened to 500, and Minnesota had developed a shortage of 1,600 nurses (see charts below). During the same period, district states with an adequate supply of nurses saw their margins shrink. In Montana, for instance, the nursing surplus fell from 900 in 2000 to 200 in 2005.

HRSA's projections through 2015 are not what hospital administrators want to hear. Within eight years, demand for nurses is expected to exceed supply in every state in the country.

Like all such models, HRSA's is based on assumptions. If those assumptions are wrong, the model's predictions may not come to pass. But even under rosier scenarios examined by HRSA, little relief is in sight. Even if market conditions changed drastically-nursing programs turned out 90 percent more graduates, for example, or the U.S. population grew 20 percent less than expected-demand for RNs would still outstrip supply in 2020.

Higher wages—and ages

Labor shortages generally take care of themselves. Employers complaining about scarce labor usually mean they can't hire enough workers at the wages they want to pay. Basic economics dictates that if those employers raised wages, workers would flock to fill job openings.

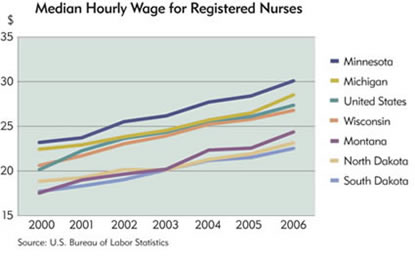

Wage data indicate that nursing compensation has in fact increased in the past five years, both nationwide and in the district. Nationally, average wages for RNs increased 34 percent from 2000 through 2006, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In contrast, wages for all occupations rose 20 percent in the same period, and wages in the overall health care industry increased 28 percent.

All district states have seen an increase in nursing pay, albeit to differing degrees. In Minnesota and North Dakota, median hourly wages for RNs increased almost 5.9 percent from 2005 to 2006, outpacing nationwide wage gains.

So why aren't more nurses rushing into the labor market to collect fatter paychecks? The most likely explanation is demographic change, the same force driving up demand for health care. "It's affecting both the supply and demand sides of the market," said Peter Buerhaus, a professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., who studies the nursing labor market.

The average age of the U.S. population is increasing and with it demand for health care. At the same time, nurses are graying along with their patients. In 1980, nurses 25 to 29 years old made up the largest age group in the workforce. By 2000, nurses in their forties made up the biggest age group. As older nurses retire, not enough younger nurses are coming along to replace them.

Young women (roughly 90 percent of nurses are women) have more career options today than they did a generation ago. And many nurses are apparently fed up with conditions in the workplace. In surveys by state nursing boards, nurses complain about higher caseloads and mandatory overtime—stress inducers that are exacerbated by a scarcity of nurses.

Market, heal thyself

Despite these demographic realities, there's evidence that wage increases are having the desired effect, drawing more potential nurses into the labor pool. National figures and recent data for the Dakotas and Minnesota show a marked upturn in both nursing school enrollment and the number of practicing nurses.

In South Dakota, for example, enrollment in RN programs increased about 80 percent between 2000 and 2006, and in North Dakota, it rose 77 percent. Both states saw similar increases in LPN programs. Nationally, the number of students enrolled in four-year nursing programs increased 10 percent in 2006 over the preceding year, while the number of graduates jumped 17 percent, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

Moreover, more nurses are putting their skills to work in the marketplace. In Minnesota, the number of licensed RNs has risen 20 percent since 2000, and over about the same period in North Dakota, the ranks of licensed RNs have swelled 8 percent. Nationally, RN licensure increased by roughly the same amount between 2000 and 2004, the latest year for which data are available.

These significant changes in the nursing workforce and student body have prompted a reevaluation of projected shortages. A consulting firm that worked with HRSA on its shortage estimates is revising those figures for later publication. The addition of several hundred thousand RNs to the national nursing workforce would reduce the projected shortfall in 2020 by as much as a third, even if demand remained unchanged.

Yet the health care industry still faces long-term challenges in nurse recruitment and retention. The supply of RNs may have increased due to wage hikes, but the nurses entering the market today are primarily older nurses returning to the job after time away, Buerhaus said. So the recent surge in nurses for hire doesn't necessarily mean that the search for a few good nurses will end anytime soon.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.