With all of the talk of high land and crop prices, it's easy to forget that not everyone in agriculture is benefiting. Many livestock operators, as well as young farmers looking to get into almost any area of agriculture will tell you these are not the best of times, thank you very much.

Livestock producers are bearing the brunt of high crop prices because much of the grain grown in the United States—especially corn—is consumed by livestock. Five-dollar corn might bring tears of joy to a crop farmer, but will make a livestock rancher sweat bullets.

Lisa Heggedahl owns Adah Oaks Angus, a cow-calf operation in Hayfield, Minn. She also sits on the Minneapolis Fed's Advisory Council on Agriculture. You'll have to forgive Heggedahl if she's not doing cartwheels in the field over high crop prices. She said her feed costs today are more than three times higher than last year, and four times higher than in 2006. At the same time, "my feeder calf prices are lower compared to both years, and breeding stock sales were about the same."

She can't grow her way out of the problem. She raises her own forage, but the cost of fertilizer, fuel and other supplies needed to grow decent feed have skyrocketed as well.

"For someone in my position who does not raise corn or soybeans for market, these [input] increases are devastating to my bottom line. I can't offset these costs with grain sales," Heggedahl said. She's looked for alternatives, but can't find any. Sweet-corn silage is available from a local canning operation, but that's been locked up by large feedlot operators so they could in turn—and somewhat ironically—convert their own corn silage and hay acres to soybeans and corn for sale on the open market. Local horse owners have also pushed hay prices "sky high," according to Heggedahl.

The situation may be even worse for hog farmers, because pork prices are soft and costs are high. An April U.S. Department of Agriculture outlook report on the hog market said that many farrow-to-finish operations are losing $25 to $35 for every hog produced and sold.

High land prices are also causing problems. Jodie Hickman, head of the South Dakota Cattlemen's Association, said that grassland values have steadily increased throughout the state. With high crop prices today, "there is so much incentive to break grasslands and convert them to crop production," she said via e-mail. The problem is exacerbated by government insurance programs that protect crop farmers in the event of drought or other natural disaster; no similar program exists for livestock operations.

Many sources also pointed out that high and rising land costs are a big impediment to future generations of farmers and ranchers. "Younger producers are faced with renting more and buying less," said Curt Everson, head of the South Dakota Bankers Association. "They'd like to be buying, but at today's prices it's a little scary." He added that entry-level farmers often don't have a strong enough balance sheet to qualify for a real estate loan.

Most states—including all district states—have programs specifically designed to help farmers starting out finance a new operation. The programs typically partner with a bank to help write down the cost of a real estate or other loan for a young farmer. Ironically, many such programs have seen participation wane over the past several years. South Dakota allocates $10 million annually to finance its Beginning Farmer Bond Program. But the program has made fewer loans in recent years and has never lent all available capital in a given year, according to Terri LaBrie Baker of the state Department of Agriculture.

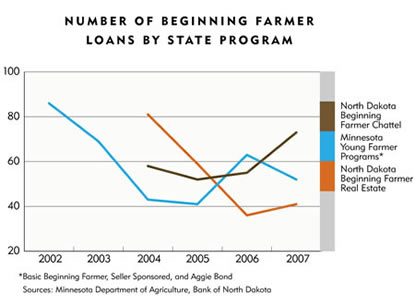

Participation in a similar real estate loan program in North Dakota has also fallen despite the fact that the net worth cap and maximum loan amounts were increased significantly in August 2005. On the other hand, participation in a similar program for chattel loans has been increasing over the past few years.

Minnesota has three programs assisting young farmers. Although they've zigzagged a bit, collectively they have seen a steep drop in participation recently (see chart). Minnesota officials gave several reasons for the volatility. For example, as land prices go up, the farmer's required equity contribution goes up as well, which can be difficult to scrape together. But probably the biggest reason for the flux in program participation—mentioned by officials in several states—is the fact that these programs are very sensitive to interest rates.

The floor on program loan rates can only go so low (and is usually based on the method for raising a program's capital, like the sale of general obligation bonds). In recent years, conventional loan rates from banks have been low enough that state assistance programs don't add much financial value. "As commercial (loan) rates rise, we see more activity in our program," said Jim Boerboom from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

Several others involved in ag financing noted that farming has always been a capital-intensive endeavor. High land prices don't make it any easier, of course, but the bar was already set pretty high.

Peter Sheppard, also with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, said that "it's more exaggerated" financially for young farmers getting started. Assistance programs can help those trying to get over the financial hump, but Sheppard said that familial or other connections are necessary to get anywhere near the hump in the first place. "You still need a fairy godmother somewhere."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.