The new farm bill, officially called the 2008 Food, Conservation and Energy Act, was authorized in May, almost a year later than originally intended, and only after a congressional override of a presidential veto. It is more complex than any previous farm legislation, largely because of the broad range of interest groups that participated in the farm bill debate and concerns over funding sources for new and old programs.

For sheer size, the new farm bill outstrips all of its predecessors with more pages, more regulations, more programs for producers (including new sections for livestock producers and horticultural and organic farmers), conservation and energy, and a substantial increase in food assistance and other nutrition programs. In short, the legislation provides for more of almost everything to do with agriculture and nutrition, with the exceptions of agricultural research and subsidies to agricultural insurance companies. It retains almost all of the policies that were established or renewed in the 2002 farm bill (though several have been relabeled), but also adds new programs. The result is an even more complicated agricultural policy environment than before.

For sheer size, the new farm bill outstrips all of its predecessors with more pages, more regulations, more programs for producers (including new sections for livestock producers and horticultural and organic farmers), conservation and energy, and a substantial increase in food assistance and other nutrition programs. In short, the legislation provides for more of almost everything to do with agriculture and nutrition, with the exceptions of agricultural research and subsidies to agricultural insurance companies. It retains almost all of the policies that were established or renewed in the 2002 farm bill (though several have been relabeled), but also adds new programs. The result is an even more complicated agricultural policy environment than before.

The most substantive changes in the 2008 farm bill concern U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) nutrition programs, which will increase the amount of food assistance and school lunch benefits available to current program participants and substantially expand the number of households that can participate in those programs. The law also introduces a new, optional commodity program (called ACRE) for producers of major commodities like wheat, corn and soybeans and a new disaster program.

Most other innovations in the 2008 farm bill are relatively minor in terms of their substance and funding implications. However, changes to the public agricultural research budget, and mandates to reallocate substantial funds to research programs for minor crops, may adversely affect the agricultural sector’s overall productivity growth rate. These changes are being made despite evidence of a world food crisis, concerns about high domestic food prices and, at least for a while, increased demand for major food-and-feed crops like corn for fuel.

Finally, current estimates of the costs of the 2008 farm bill assume that prices for major commodities will remain relatively high, at least in 2009 and 2010. But if prices for wheat, corn and soybeans return to close to their long-run averages, then farmers in the Ninth District and elsewhere in the nation will receive much larger benefits from the bill’s provisions than current estimates suggest.

Policy background

The language of the 2008 farm bill reflects the influence of various constituencies, both old and new. Traditional participants included producer-based crop and livestock groups, general farm and ranch organizations such as the Farm Bureau and the National Farmers Union, agribusiness groups and firms, and lobbies that support funding for nutrition programs.

Newer players were also influential. Bioenergy interest groups were successful in expanding programs and funding to provide ethanol and biodiesel production subsidies and for research into the use of agricultural biomass for fuel production. Environmental groups, ranging from the Sierra Club to the Environmental Defense Fund, were effective in expanding funding for, and broadening the scope of, conservation programs. Horticultural and organic producers, largely ignored in previous farm bills, also obtained funding for research and marketing programs for their products. The insurance industry was active, but less successful, as it sought to maintain its subsidies from the federal crop insurance program. Agricultural research funding lost out because farm groups preferred to obtain direct payments to producers and were skeptical about whether new funding would be allocated to agricultural production research instead of environmental, conservation and rural development efforts.

Farm bill funding

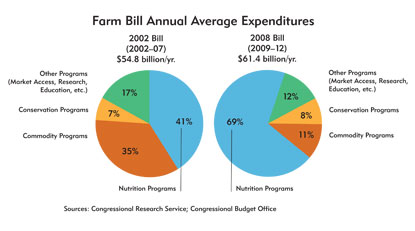

Nutrition legislation takes up a small share of 2008 farm bill legislation (one of 13 sections or “titles”). However, over the law’s five-year duration, nutrition programs will receive the lion’s share (almost 70 percent, or $209 billion) of the $307 billion in projected spending. Annual average spending on nutrition programs in the coming five years (estimated at $42 billion) will increase by about 86 percent over the $22.5 billion average under the 2002 farm bill. Commodity program payments to farmers are estimated to be $35 billion (11 percent of total spending), while conservation programs are expected to receive $25 billion (8 percent). On an annual basis, average spending from the new farm bill will increase by about $6 billion a year, or about 12 percent, to $61 billion, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (see charts).

However, the CBO is forecasting much lower subsidies from commodity and conservation programs over the next four years than over the previous five years. This is not because of program changes but because commodity prices are forecasted to be well above their historical averages and current support prices. If commodity prices return to pre-2006 levels, however, spending on commodity programs would be substantially higher than the current CBO estimates.

Ninth District implications

Almost all homes in the Ninth District will be affected by the changes introduced in the 2008 farm bill. Changes in nutrition programs, for example, will benefit many nonfarm households, as well as some farm households. Commodity, crop insurance, disaster relief, conservation and other programs will have direct effects on farmers and ranchers, and indirect effects on the communities in which they are located.

Nutrition

Perhaps the most important changes for many households are embedded in the new nutrition programs. Poverty is more pervasive in rural counties than in most metropolitan areas, and the Ninth District is disproportionately rural, with pockets of deep poverty, particularly on Native American reservations.

Funding for the Food Stamp Program, renamed the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), will be increased substantially. Benefits received by the average household participating in the program will increase immediately and, in the future, be indexed to inflation. In addition, more households will be able to participate because of changes in eligibility rules that increase the maximum limit on the amount of assets a household can have (from $2,000 to $3,000) and still receive program benefits.

Federal funding will also increase by over $100 million a year for emergency food assistance, which helps food banks, food pantries and soup kitchens fight hunger in local communities. The new law also authorizes an additional $100 million a year to buy fresh fruits and vegetables for school lunch programs. The CBO estimates that over 400,000 people in the Ninth District (including all of Wisconsin) will benefit from these changes in nutrition programs.

Commodities

When it comes to commodity programs, the implications for farm incomes are a puzzle. Major crops—corn, wheat, barley, soybeans and other oil seeds, grain sorghum and oats—have benefited from price support and other subsidy programs since the early 1930s. The 2002 farm bill created a three-pronged income support program for farmers of these commodities consisting of loan rates, direct payments and countercyclical payments. These programs are continued, but with some modifications. In addition, farmers have the option of a new revenue-based commodity program if they opt out of some elements of the existing commodity program.

Loan rate programs, essentially complicated price support programs, have been around since 1948. They create a price floor for commodities. When the market price of a crop or dairy product is lower than the loan rate or support price, farmers are able to loan or sell their commodities to the federal government at the support price. Alternatively, farmers can elect to receive a deficiency payment equal to the difference between the support price and the lower local market price (as estimated by the USDA) and maintain responsibility for selling their own crop. The 2008 farm bill increases loan rates for several crops produced by farmers in the Ninth District, including wheat, barley, oats and other oilseeds, by between 5 percent and 10 percent, though in most cases the new support prices are well below current and expected future market prices.

Two changes have been made to the dairy price support program, but neither is expected to have substantive implications. The program for manufactured milk has shifted to price supports for butter, cheese and dried milk, but provides the same level of support, and the price support for liquid milk is now linked to feed costs.

The sugar program received a significant upgrade. The sugar loan rate, currently 22.9 cents per pound, will be raised more than 5 percent (to 24.09 cents) in three annual steps from 2009 to 2011. Many farmers in Minnesota, Montana and North Dakota raise sugar beets and participate in the federal sugar program, and the benefits to these and other sugar producers are likely to be substantial: World market prices for sugar are often well below the loan rate, and the U.S. sugar program, which includes domestic production restrictions and import quotas, is intended to ensure that domestic sugar prices do not fall below the loan rate.

Since the 1996 farm bill, farmers with a long-term history of producing major commodities like wheat, corn, barley and soybeans have also received direct payments, which are based on historical average plantings and yields, and are “decoupled” from current production. The 2008 farm bill reduces these payments to all farmers across the nation by 2 percent in 2009, 2010 and 2011, but returns them to their 2007 levels in 2012. The impact of these reductions on farm incomes in the region will be modest but adverse.

Countercyclical payments (CCPs) are the third residual commodity program from the 2002 farm bill. Farmers receive these payments (based on a complicated formula) when their crop prices are low. The payments are tied to the same history used to establish their direct payments, and not to current production. Although producers have received comparatively little from this program of late, the new farm bill gives small increases in the target price (which triggers the payments) for most commodities, including wheat, barley, oats, soybeans and other oilseeds, but not corn.

On balance, these commodity program changes should have little effect on payments to farmers for most crops. However, there is an important new wrinkle. Largely at the request of corn and soybean producers in the Midwest, Congress developed an alternative commodity program called the Average Crop Revenue Election. Producers who elect to use ACRE have to forgo any countercyclical payments and take a 20 percent cut in the direct payments and a 30 percent reduction in the loan rates or price supports for which their crops are eligible. In addition, if they opt into the ACRE program when it becomes available in 2009, they must do so for all of their commodity program crops and stay in the program through 2012.

The ACRE program provides enrolled producers with payments when the average statewide revenue per acre falls below 90 percent of its estimated historical average. But the devil is in the details. There’s another complicated formula involved, one that uses a five-year history for yields, but only the two most recent years for average prices. That might sound innocuous, but it allows the program (and participating farmers) to immediately capture the financial effects of the recent high prices for crops like wheat, corn and soybeans. As a result, per acre revenue benchmarks are likely to be high for many crops in both 2009 and 2010. If prices for wheat and other commodities return to pre-2007 levels, the ACRE program payments would be relatively large in those early years, making it an attractive option to district producers.

In general, it’s not clear whether the new farm bill will increase or decrease payments to producers. However, the ACRE program’s structure will probably benefit producers of wheat, barley, soybeans and corn if current prices drop significantly.

Commodity payment limitations

Much heat has been generated over the issue of payment caps to wealthy farmers and landowners who do not farm their own land. The new farm bill prevents any program payments to landowners with adjusted gross incomes over $500,000 or to farmers with adjusted gross incomes over $750,000. The effects of these changes in the Ninth District are likely to be minimal, as relatively few farmers and landowners have sufficiently large incomes for these restrictions to come into effect. Though a couple of thousand district farmers and an unknown number of landowners might have gross incomes that exceed those caps, there are numerous ways of writing down adjusted gross income for tax purposes.

A potentially more important change involves the modification of the so-called three-entity rule to a two-entity one. Under the new legislation, an unmarried person operating a farm or ranch can receive a maximum of $105,000 in direct and ACRE or countercyclical payments, but a married couple jointly running a similar operation is eligible to receive $210,000. The now-defunct three-entity rule allowed qualifying operations up to $315,000.

Crop insurance and disaster aid

Farms and ranches have come to rely heavily on federal crop insurance programs as a means of enhancing farm revenues and reducing their year-to-year variability. The program effectively subsidizes both producers’ policy premiums and private insurance companies that market policies and assess losses. Under the new farm bill, premium subsidies will remain mostly unchanged, but payments to the agricultural insurance companies for administrative and marketing costs will be reduced from about 21 percent to 18 percent of the premium.

In addition, the 2008 farm bill creates a new standing disaster aid program, called the Supplemental Agricultural Disaster Relief Program. Funded at about $1 billion a year, it is designed to provide the same level of support in counties declared natural disasters as they would have received on an ad hoc basis. Congress also introduced an additional disaster aid program targeted to livestock producers in counties suffering from drought. Under this program, mandatory payments for forage and pasture loss are triggered by the U.S. drought monitor index. So it is likely to provide more reliable drought relief compensation for livestock operators in many northern Great Plains counties where severe drought is a frequent occurrence.

Conservation

Beginning in 1985, Congress authorized a suite of voluntary conservation programs designed to maintain and improve environmental amenities, including wetlands, wildlife habitats and reduced soil erosion. Under these initiatives, which included the Conservation Reserve (CRP), Wetlands Reserve (WRP) and Healthy Forest (HRP) programs, farmers are paid to take land out of crop production and place it in conservation-based uses, re-establish and maintain wetlands or provide other environmental amenities.

Both agricultural producers and environmental groups have been highly supportive of these programs. However, some farmers want to put CRP land back into production given high corn and wheat prices. In response, and partly because of concerns over bioenergy feedstocks, the 2008 farm bill mandates a reduction in land included in the CRP from the current level of about 39.2 million acres to 32 million acres by 2010, although federal funding for CRP payments is to remain stable at $2.1 billion per year. On the other hand, the bill also mandates that the USDA take the steps needed to expand the areas enrolled in WRP and HRP and increases funding for payments to farmers under those programs.

Working lands conservation programs have been important elements of the previous farm bills. In terms of funding, the two major programs are the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). The EQIP program, with increased funding of about $1.1 billion, provides subsidies to farms and ranches for the purchase and installation of materials and equipment needed for innovative approaches to agricultural production that also provide environmental benefits, such as reduced soil erosion and improved water quality. Funding under EQIP is also available for producers who are switching to the production of organic crops.

The CSP, essentially a continuation of the Conservation Security Program, pays farmers and ranchers to adopt practices that conserve environmental amenities. Funding for this program was somewhat increased in the new farm bill, and an individual farm can receive up to an average of $40,000 a year over a five-year contract period. There are concerns about whether the program does much good, as farmers and ranchers are already required to adopt some conservation practices in order to participate in subsidy programs. However, the CSP is popular with farm groups and environmental lobbies and also has “cross aisle” political market appeal. For example, U.S. Sens. Tom Harkin (an Iowa Democrat) and John Thune (a South Dakota Republican) strongly supported CSP in public debates on the Senate floor.

The 2008 farm bill also continues support for a plethora of more modestly funded conservation-related initiatives. These include programs that fund easements to protect pasture and grassland, maintain wildlife habit, enhance agricultural water quality, encourage conservation research and provide public access to wildlife habitat.

Energy

The 2008 farm bill has a wide array of energy programs. Most are funded at relatively modest levels and generally provide biofuel subsidies targeted to processing rather than feedstock production. Total funding for energy title programs, several of which were originally scheduled to end in 2006 or 2007, is about $1.1 billion between 2008 and 2012 (an average of $275 million per year).

Much of the emphasis is on cellulosic biomass. For example, the biorefinery assistance program will receive over 25 percent ($320 million) of energy funding to provide loan guarantees for the private sector construction of refineries to process “advanced” biofuels. An additional $300 million goes to expand production of advanced biomass fuels, and $118 million is allocated for advanced biomass research and development. The latter is needed because currently available cellulosic technologies cannot yet produce biofuels at competitive prices.

Biofuels like switchgrass, forest biomass and other feedstocks are problematic because they are expensive to transport. So the new farm bill authorizes the secretary of agriculture to establish project assistance areas where biofuel processors will receive subsidies of up to $45 per dry ton. These programs may benefit communities in Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where rainfall is more plentiful and, as a result, biomass production is more intensive.

Horticulture and organics

Horticultural and organic producers have complained about lack of inclusion in past farm bills. Congress has responded by providing $100 million annual block grants to individual states to facilitate domestic and international marketing of organic products as well as traditionally grown fruits, vegetables and other horticultural crops. The bill also provides $400 million for a five-year program to combat the adverse impacts of invasive species on fruits, vegetables and other crops.

Between 2008 and 2012, about $78 million will be allocated to organic research and extension programs and $230 million to research on specialty crops. However, this represents a reallocation of research funds from other agricultural production programs for major food and feed commodities like wheat and corn.

The more things change

The early farm bill negotiations were characterized by dramatic proposals and strident rhetoric about the need for major changes in farm programs and cuts in government subsidies. Yet despite a strong farm economy and the absence of major crises, in the end the 2008 farm bill involved relatively few changes to existing programs and even added a few new initiatives to benefit farmers and ranchers. Whether that’s good, bad or indifferent likely depends on what you thought of previous farm bills.

Vincent Smith is a professor of economics and director of the Agricultural Marketing Policy Center, Montana State University.