The iron ore industry, like its product, has been buried and unearthed so many times over the past few decades that it's hard to know whether to have a christening or a wake.

Recent announcements of plans to expand mining operations, build new processing facilities in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Minnesota, and bring the first-ever steel mill to Minnesota's Iron Range point to an industry rebirth. World demand for iron ore and steel has surged, pushing up prices and making expansion and new development projects economically attractive, and giving the industry renewed relevance in both regions.

Folks from the Iron Range and U.P. have been down this path before. The industry has been in long-term decline, but periodic plateaus and brief periods of growth have rekindled nostalgia for this high-paying industry. But some are starting to believe there might be a healthy foundation beneath the latest iron ore revival.

For starters, the number, scale and uniqueness of proposals differ from other boom-bust cycles. Minnesota's Iron Range has long had but a single product: taconite, a processed pellet that is about 65 percent iron ore, which is exported mostly to steel mills on the Great Lakes that use traditional blast furnace technology. New proposals would broaden the base of iron products, from a new higher-content iron nugget to finished steel.

For example, Mesabi Nugget Delaware LLC is touting the region's first plant to produce high-iron nuggets. It's located in Hoyt Lakes, Minn., at the site of the former LTV taconite mine that shut down in 2001, putting 1,400 out of work. The plant will generate a nugget that is 96 percent iron (also called direct-reduced iron), allowing the plant to sell output to steelmakers using newer-generation electric arc furnaces (also called mini mills), which currently produce the majority of U.S. steel.

The new mining endeavor expects to employ about 500 construction workers and 100 permanent employees when it opens in 2009, nowhere near the former employment level, but it is only one of several mining operations promising a new era of good-paying jobs for local workforces and communities.

Minnesota Steel Industries LLC, part of India's Essar Steel Holdings Ltd., is going one better: It is proposing a new plant to produce direct-reduced iron. But it also wants to build the region's first finished steel plant, slated for an area west of Nashwauk, Minn. This would be the first North American facility to combine mining and steelmaking on the same site and, when completed, is expected to employ about 700 by 2011.

Over in the U.P., Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. (CCI) will be constructing a direct-reduced iron plant at its Empire Mine near Palmer. The company announced this project last summer, just months after it had talked publicly about having to shut down the mine entirely within a few years. CCI expected to apply for environmental permits this spring. Nugget-making may begin in late 2009 or early 2010, and the company will employ 300 to 500 temporarily in the construction phase.

Though the mine will likely downsize its permanent workforce, the project will extend the life of the mine by 15 to 20 years because a smaller amount of ore is needed to produce nuggets, according to Dale Hemmila, CCI's district manager of public affairs in Michigan. He added that the nugget process for steelmaking in electric furnaces reduces emissions of mercury, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide and particulates into the atmosphere. Equally important, the plant's output will better position the company among the growing market of mini mills.

Even the good old taconite pellet is seeing renewed enthusiasm. Riding the wave of high prices and demand, two Minnesota taconite pellet plants are expanding. KeeTac is reopening an idle processing line at its mine near Keewatin, adding 75 permanent jobs after 500 construction workers finish. In addition, Northshore Mining Co. in Silver Bay is expanding its operations, adding 800,000 tons per year of iron ore pellets along with 30 new jobs and 100 temporary construction workers.

Satiating worldwide appetite

These projects are not hanging on a wing and a prayer; all of this is occurring because the global appetite for steel—and by extension iron ore, its main input—has skyrocketed over the past several years, and that trend appears likely to continue in the near future.

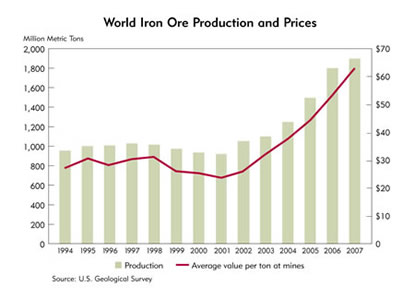

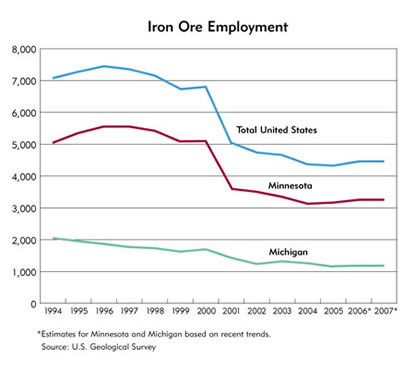

Nary an expert would have predicted this turn of fortunes even a half-dozen years ago. From about 1995 to 2001, iron ore production both worldwide and in the United States (almost all domestic iron ore comes from Minnesota and the U.P.; see charts) was in the dumps, dropping 10 percent over this period and taking local mining employment with it.

You might say iron ore has been cooking ever since. Thanks to seemingly insatiable demand, worldwide ore production more than doubled from 2001 to 2007, from 916 million metric tons to 1.9 billion tons. Ironically, the Iron Range did not see a similar boost in production during this period, in part because much of the mine infrastructure had already been mothballed, and expensive restarts and expansions of existing facilities couldn't be justified given the volatility common in iron and steel markets. But rising global consumption was pushing up prices for all producers, which set the stage for the current mini boom unfolding on the Iron Range.

In 2001, the price for U.S. ore was just $24 per metric ton. By 2004, it had risen to $38 and hasn't looked back since. In the fourth quarter of 2007, Cleveland-Cliffs (owner of a handful of Minnesota and U.P. mines) reported that it received $66 per ton. Experts are expecting prices to go even higher this year; last July, the U.S. Geological Survey said industry bankers expected prices to increase this year between 18 percent and 25 percent. Contracts negotiated this year between Chinese steelmakers and Brazilian ore producers have seen even steeper increases.

Peter Kakela is a professor of resource management at Michigan State University and a widely cited expert on the iron ore industry. He said price increases have resulted simply from rising demand and a continued boom in buildings and infrastructure worldwide. "China is leading the way," Kakela said, but he also noted demand from Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa. Other sources also pointed to a continuing construction binge in the United Arab Emirates induced by a gusher of oil revenues. With continued strong demand for steel, iron ore prices this year "could top $100 a ton," Kakela said.

Along with strong prices, new mining activity on the Iron Range is also driven by the modernization that's occurred over the past four to five years, such as greater plant efficiency and restructured mine management, according to Craig Pagel, president of the Iron Mining Association of Minnesota in Duluth. Pagel also cited broadened ownership in mines and mills—for example, the agreement between Mesabi Nugget and Kobe Steel, and the partnership between Minnesota Steel and Essar Steel Holdings.

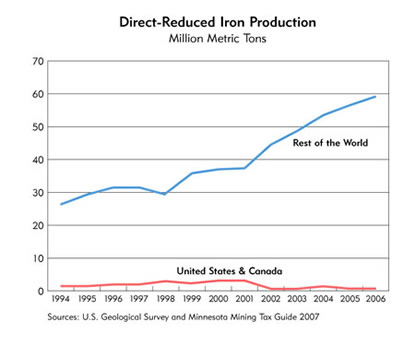

New investments in direct-reduced iron plants are also very strategic; not only do mini mills have a majority market share, but that market share continues to grow. Mini mills use no taconite, only scrap and direct-reduced iron. Worldwide production of direct-reduced iron has been growing strongly over the past decade and in lock step with the rise of mini mill production; virtually none of that direct-reduced iron was produced in either the United States or Canada as of 2006 (see chart). Kakela overheard an industry colleague say that "iron nuggets are like cocaine—you've got to have more."

Rational exuberance?

Iron Range Resources (IRR) is a state agency in Eveleth, Minn., charged with developing the resources of the state's mining region. One of its slogans is "Business Is Beautiful," and the spate of recently announced projects has given new meaning to those words.

On top of an expanding iron ore industry, three proposed nonferrous mining operations include new underground and open pit mines on the Iron Range. The energy intensiveness of mining projects has sparked several new energy proposals as well. (See sidebar [PDF] for an overview of planned projects on the Iron Range.) Over in the U.P., a nonferrous metals mine near Marquette has also been recently approved, and the region is seeing additional exploration activity.

Minnesota is staring gladly at the promise of perhaps 2,500 permanent jobs, if all the projects develop as proposed. That's not even counting the construction workers, who may number in the thousands. It's been suggested that every new mining job creates two to three other jobs, largely in the service sector, said Sandy Layman, commissioner of the IRR in Eveleth.

To help communities prepare for the onslaught of construction workers, the IRR is coordinating a task force to look at housing and workforce issues. The agency is also working with the mining companies' project leaders in an attempt to coordinate their construction timetables to keep those workers continually employed.

Some have expressed concern about available labor for permanent jobs. A mid-March newspaper report said 300 or more Iron Range mining jobs are already open or are expected to open in the near future.

But the Iron Range is near full employment as health care, tourism and other industries have seen strong growth in the wake of mining's struggles. A Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development report from August 2006 also warned that mining is one of the industries affected by aging baby boomers, with nearly 18 percent of workers over the age of 55 in 2004. Another DEED report on job vacancies noted that mining vacancies were up 56 percent over the second quarter a year earlier.

But many believe labor markets will sort themselves out when the hiring starts. Richard Lichty, recently retired economics professor at the University of Minnesota-Duluth, pointed out that unemployment on the Iron Range is not high, but "under-employment is." He noted that some are working less than they want, or earning less than their skills might call for. And because of a general lack of good jobs, young people are leaving who might otherwise want to stay.

Layman optimistically noted that the size and significance of these projects "have the ability to bring a new and young population" to the Iron Range. Or perhaps as Lichty said, "New workers may not be coming in, but staying in."

Hard rock café

But even amid the boom, one can hear the echoes of iron ore busts in years past and see an industry unlikely to reclaim its former luster. In spite of current activities, mining is simply no longer the statewide or regional economic driver it once was.

To U.S. steelmakers, iron ore from the U.P. and Minnesota is still a critical input. The bad news for workers and communities is that plants can crank out more iron in less time, thanks to technological and other productivity improvements. Iron mining jobs continue to be among the best paid in the region—$25.61 per hour in 2006—but the number of jobs in the sector has been in steady decline. Even a big bump in employment won't put it anywhere near levels of a decade ago (see chart), to say nothing of levels in the late 1970s, when the industry employed some 14,000 workers.

Thomas Power, professor emeritus of economics at the University of Montana, prepared a study of mining in Minnesota for environmental watchdog groups, the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy and the Sierra Club. Power looked at employment numbers in mining compared to the rest of the workforce and determined that mining is an ever-smaller segment of the regional economy. By 2005, according to Power, earnings in metal mining were the source of just two-tenths of 1 percent of personal income in Minnesota.

Even in counties with significant mining operations, the prevalence of mining earnings has dropped considerably. Among Iron Range counties, for example, Lake County relies most on mining for earnings. Yet its dependence on such earnings declined from a high of 43 percent to just 13 percent by 2005, according to Power.

No one is wishing away the projects, but things are different. For example, projects are probably being scrutinized more closely than in the past; residents are more concerned about detrimental environmental effects, in part because tourism has become an important economic contributor in the region.

Lichty was involved in preparing economic impact studies for recent proposals from Minnesota Steel and Polymet, a precious-metals mining company. He agreed with Power that an independent cost-benefit study should be done to better assess the full impact of these mining projects. He noted that impact studies are often prepared quickly and sometimes make assumptions, whether about employment or environmental effects, that may need more careful vetting.

At the end of the day, all of the perceived and anticipated benefits and costs of the new mining projects might not signal a full rebirth of the industry. But it's still an awfully nice shot in the arm, particularly considering the mining sector's history, as well as the tough current conditions that much of the nation finds itself in.

Said the IRR's Layman, "When recession is on everyone's mind, in northeastern Minnesota, we're looking at an economic uptick."