If recent ballot initiatives are any indication, the Twin Cities might soon be encircled by prairies, woods and wetlands shielded from development. This past November, the voters of Minnesota's Washington County, a fast-growing area just east of the Twin Cities, agreed to tax themselves an extra $20 million to preserve open space. The vote gave fiscal backing to the conclusion of a March 2006 survey of county residents: Growth and development were identified as "the most serious issue" facing the county by 37 percent of residents, far eclipsing other concerns like taxes and education.

In smaller Twin Cities' suburbs to the north and west, Andover and Plymouth, voters approved a total of $11 million in extra tax levies for open space and habitat protection. And in Dakota County, in the south metro, a similar $20 million open space bond passed in 2002 has protected about 4,500 acres against conversion into malls, parking lots or homes.

Minnesota voters aren't alone in their zeal to preserve wilderness. In Montana, open space bonds, each for $10 million, were adopted in Missoula and Ravalli counties in November. Half of the Missoula amount will be spent within city limits, and the rest will be split among eight county regions. Missoula city voters adopted a similar $5 million bond in 1995 and used it to protect 3,000 acres.

Nationwide, voters approved 104 of the 130 land conservation initiatives on state, city or county ballots this past fall, authorizing over $5.7 billion. According to the Trust for Public Land, the sum is the highest in any election since it began tracking such initiatives in 1988.

Voter willingness to pay for land conservation is evidence of public appreciation of open space, and the not-unreasonable concern that once developed, natural landscapes are difficult or impossible to recover. Open space bonds are often used to purchase land, just as Missoula's 1995 funding bought most of the southwestern face of picturesque Mount Jumbo to prevent it from succumbing to development pressure.

Direct land purchases funded by voter-approved bonds are just one of a number of measures that use incentives rather than regulations to protect forests and fields. Two of the most prevalent efforts of this sort are conservation easements and preferential tax assessment programs. Both are used extensively in Ninth District states. Unfortunately, some who have studied them raise doubts about their effectiveness and efficiency.

Preferential assessment

Most states have enacted preferential tax assessment measures in order to preserve farmland. Such programs assess farm acres at their value when used for agriculture rather than at their potential market value if converted to, say, a housing subdivision or shopping mall. With their farmland assessed at the lower value, farmers incur lower tax bills and diminished pressure to sell cropland that is appreciating because of nearby development.

In Minnesota, counties have had this as an option since 1967 through a program called "Green Acres." Wisconsin adopted a farmland use-value assessment law initially in 1995, with significant revision in 2001; the law applies throughout the state. And such programs can, depending on their provisions, involve substantial sums. In a 2003 study, Wisconsin's Department of Revenue estimated that the state's law has saved farmers a total of $644 million in avoided property taxes from 1996 to 2002.

Still, some analysts argue that preferential assessment may not be a very effective means of preserving farmland. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) economists Ralph Heimlich and William Anderson wrote in 2001 that the program "has not provided a strong incentive for conserving farmland," since developers can buy agricultural land from farmers and reap reductions in property taxes by sustaining fairly minor agricultural activity until they decide to develop. Moreover, the capital gains from developing the land are likely to exceed the rollback penalties incurred. "At best," argued Heimlich and Anderson, "preferential assessment may slow the transition from rural to developed uses, but it is not a permanent solution."

Easing does it

Since preferential assessment may provide only a temporary fix, those seeking to preserve farms and forests have sought more permanent tools. Conservation easements, in many flavors, have become an increasingly popular device. (For more discussion of conservation easements, see "Not out of the woods yet," fedgazette, January 2007.)

The concept revolves around landowner property rights. Since owners possess a variety of rights with regard to their land—the right to prohibit others from entering it, for instance, and the right to use it as collateral for a loan—they're also free to sell, trade or give away some of those rights without losing other rights. An easement is the legal agreement that grants a non-owner a limited right to use the property in a designated way—say, to walk across the land.

A conservation easement grants a non-owner—usually a public agency or a qualified conservation organization—the legal right to enforce development restrictions that the landowner agrees to. Conservation easements are usually considered permanent, enduring beyond the lifetime of the current owner, but they're flexible in that owners can sometimes designate developable lots to be reserved for family members.

By preserving an owner's title, and retaining the owner's rights in most other ways, conservation easements have become popular among owners who support the preservation of undeveloped land, and both national and state laws have evolved over the past several decades to encourage their use.

Sell, transfer or donate

Conservation easements are used in a number of ways. In some cases, landowners donate the easement to the appropriate body. In others, owners sell their easement, through a purchase of development rights (PDR). And in some cases, the right to develop land is transferred: a TDR—in essence, a swap from an area with development restrictions to an area that allows development.

With a PDR, a government body or a private land trust buys development rights from the landowner—placing the conservation easement on the acreage. Deciding on the value of those rights is a tricky issue, though, involving a difficult land assessment: How much is it worth in its current use, and how much would it be worth if developed to its highest market value? The difference is the PDR price, paid to the owner by the trust or government.

TDRs are trickier still. While they're essentially market-driven transactions between landowners and land developers, they involve a careful matching of a "sending" zone (most likely in a rural area where planners are trying to discourage development) with a "receiving" area (usually in an urban core where development is encouraged).

In an increasing number of cases, however, development rights are being neither sold nor transferred, but donated by landowners. The incentive? Aside from implicit support of conservation goals, the owner is entitled to deduct the value of the donated development rights from future federal tax bills. (A few states also allow the deduction.) "So the whole thing is driven by IRS regulations" on appraisals and related deductions, according to Steven Taff, an applied economist at the University of Minnesota.

In August 2006, federal tax incentives for conservation easements were significantly expanded by Congress, allowing easement donors to raise the deduction taken in any given year from a maximum of 30 percent of their annual income to as much as 50 percent and extending the carry-forward period for deductions from five years to 15 years. The law expires at the end of 2007; its supporters hope to extend it.

Even before the 2006 change, easements have been thriving, as have the land trusts that encourage, receive and enforce them. In 1984, there were 535 land trusts holding under half a million acres, according to the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) in Bozeman, Mont. By 2005, the number of land trusts had climbed to 1,663, and they held—either outright or through easements—nearly 12 million acres, according to the Land Trust Alliance, an association of state and local trusts.

In addition to these state and local trusts, national land conservation groups, like the Nature Conservancy, Ducks Unlimited, The Conservation Fund and the Trust for Public Land, hold even greater acreage, bringing the 2005 total "conserved through private means" to 37 million acres, according to LTA, a 54 percent increase from 2000.

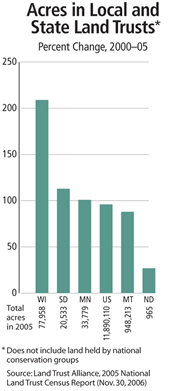

State-level data on acreage aren't readily available for national conservation groups, but the LTA does have numbers for state and local trusts. Montana has nearly a million acres held by state and local trusts, an 88 percent increase over 2000. Wisconsin's 54 trusts have far less acreage (about 78,000 acres), but that represents a 209 percent jump since 2000. Minnesota is also quite active, with about 34,000 acres held in trust in 2005, twice the acreage protected in 2000 (see chart).

State-level data on acreage aren't readily available for national conservation groups, but the LTA does have numbers for state and local trusts. Montana has nearly a million acres held by state and local trusts, an 88 percent increase over 2000. Wisconsin's 54 trusts have far less acreage (about 78,000 acres), but that represents a 209 percent jump since 2000. Minnesota is also quite active, with about 34,000 acres held in trust in 2005, twice the acreage protected in 2000 (see chart).

Even South Dakota, a relatively small player, has accelerated its land trust efforts, according to A.J. Swanson, a director of the Northern Prairies Land Trust. The trust has worked with Sioux Falls and other local governments to prevent cattle from polluting the Big Sioux river. But private citizens, not governments, are most excited about easements, according to Swanson.

"There's no shortage of interest [in easements]," he said. "Private landowners are getting more and more enthused about trying to protect the natural lay of the land."

Pros and cons

Clearly, easements are popular, but critics have highlighted downsides as well. By restricting the market value of land, easements can theoretically alter local property taxes; if one portion of a county's land is assessed at a lower value, other properties must pay higher taxes to compensate. Research seems to suggest that land use regulations of this sort may indeed increase overall property taxes in the short run but actually decrease them long term, in part by decreasing public expenditures.

Indeed, the research literature is undecided as to whether development restrictions imposed by such land preservation programs actually have a negative impact on land values, as theory suggests they would. A 2001 study of Maryland property found "little statistical evidence that the development restrictions imposed by PDR/TDR preservation programs significantly reduce farmland prices." On the other hand, a 2004 study of Minnesota land enrolled in a permanent government conservation program found that restrictions "were negatively and significantly associated with per acre sales prices."

A more certain problem is that conservation easements can be handled dishonestly. By exaggerating the appraised value of the donation, some landowners have manipulated the program to reduce their personal tax burden. According to PERC, however, "[t]he vast majority of land trusts are engaged in legitimate conservation."

Are they worth it?

The more important question: Are open space preservation efforts worth their cost? And are they truly effective? Again, the answers aren't unequivocal, in part because evaluations are rarely done. "Few empirical evaluations of policy effectiveness and impacts have been conducted," observed David Bengston, Jennifer Fletcher and Kristen Nelson in a 2004 review of open space protection programs. And effectiveness may vary by location. A recent USDA article notes that "whether the benefits of farmland protection exceed program costs may depend greatly on local conditions."

A few examples illustrate the complexity of program evaluation. It's not clear, for instance, if the charitable deductibility of easements stimulates more donations than they cost in forgone tax revenue. Moreover, the easements that private parties donate may not be particularly valuable from an environmental or amenity standpoint. Minnesota's "Washington County is an excellent example of that," said Steven Taff. "[Easements have been donated] in areas that the communities might not like to have locked up." Presumably the $20 million open space bond just passed by Washington County voters will help protect acres considered more desirable.

But neither outright purchase nor conservation easements entirely prevent land development. "There is no evidence that they stop sprawl," observed Taff. "All they do is shift ... new development to another area. There's no way you're going to lock up enough land through an easement program to stop development." And in any case, it's clear that a relatively small fraction of total land is affected directly. Montana, for example, has a total of 145,000 square miles of land. If state and local trusts hold 1 million acres of it and national trusts another million, they're protecting just 2 percent of the total.

Blending tools

Regardless of effectiveness, these programs are rising in popularity and are likely to continue. Commenting on preferential tax assessment, economist Heimlich observed via e-mail, "It is a poor tool for controlling development, made even worse by inadequate [penalty] provisions. ... Nevertheless, it is way too popular to kill-everyone in rural areas likes taking money from (owners of) more developed area land uses."

It also seems likely that open space advocates will pursue a blend of tools-both regulatory and incentive-based-by combining zoning restrictions, outright purchases of land, as well as easements, transfers and preferential assessments.

In Gallatin County, Mont., for example, county officials have used a range of initiatives. Bond issues passed in 2000 and 2004 each raised $10 million for open space protection. Those monies have been matched with private, state and federal contributions (the latter from the USDA's Farm and Ranch Lands Protection Program) and have put close to 40 square miles into purchased easements or outright fee-simple ownership. The county is also hoping to combine density regulation with a TDR program to shift development from rural lands to urban areas.

"We're actually doing all three [types of open space programs]," observed County Commissioner Joe Skinner. "We've got the open space bond, so taxpayers are contributing some to conservation. With this density regulation, I'll be the first one to admit that the rural land owners are probably going to be giving up a little bit of their value. And then with the TDRs, I think that the brunt of conservation will be paid by people buying homes here."

So, ultimately, the impetus for blending a variety of programs to mitigate the impact of rural sprawl may rest in the realities of political economy and the recognition that if people want open space, they'll have to pay for it. "That's one thing that I've said all along through this," noted Skinner. "If you're going to do conservation, it costs somebody something."