When the Air Force handed over the keys to Sawyer Air Force Base in September 1995, officials in Michigan's Upper Peninsula predicted economic doom and gloom for the region, as they were losing one of the U.P.'s top employers, and one of its most populated communities.

When the Air Force handed over the keys to Sawyer Air Force Base in September 1995, officials in Michigan's Upper Peninsula predicted economic doom and gloom for the region, as they were losing one of the U.P.'s top employers, and one of its most populated communities.

Sawyer Air Force Base, located about 22 miles south of Marquette, was one of the first bases to close in a round of Pentagon cost-cutting measures in the early '90s. Predictions of economic disaster were rampant at that time: Thousands of military and civilian jobs would be lost, not to mention the $80 million to $100 million spent by military families annually in Marquette County. Northern Michigan University was expected to lose 500 students, or about 6 percent of its enrollment. Housing prices would plummet and K-12 schools would be empty as parents affected by the base closing pulled up stakes and looked elsewhere to restart careers.

That was then ... but not for long

Like a mother who has no memory of the pain of childbirth, those involved with Sawyer's closing and rebirth have simply put all that behind them. But some of those predictions were fairly accurate for a time.

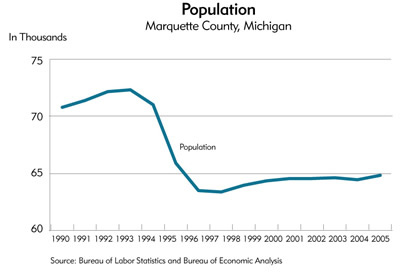

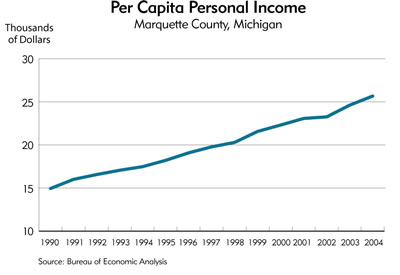

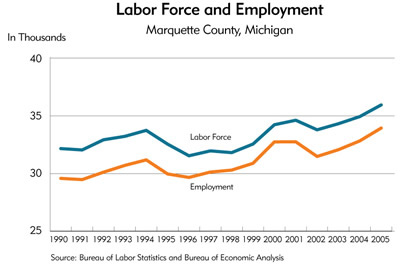

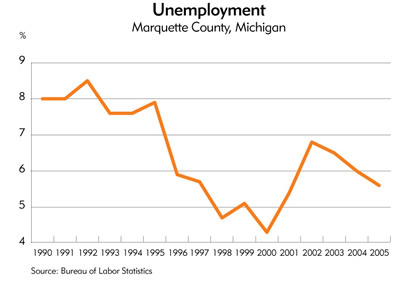

There was pain, to be sure. Government employment data show that military employment in the county dropped from its peak of 3,600 in 1993 to 167 (all nonbase personnel) by 1996. Another 800 federal civilian jobs were lost as well. Marquette County's population followed in tow, dropping precipitously by 7.4 percent in 1995, followed by another 3.8 percent in 1996. Not surprisingly, total county employment went down; ironically, so did unemployment, most likely due to an out-migration of jobless people who figured their prospects were better elsewhere given the base closure. Total income in the county fell 3.5 percent in 1995. Local K-12 enrollment was devastated, tumbling from about 3,000 students to 1,200. Northern Michigan University suffered an instant student decline of 7.7 percent and 5.8 percent in fall semesters 1994 and 1995, respectively, with the greatest drop in undergraduate enrollment.

But before the epitaph was even dry, the region started seeing an upswing. Personal income rebounded by 1997 and has risen steadily ever since. From 1996 to 2000, the county added 3,000 jobs—finally surpassing the county's 1994 employment peak—and then another 1,000 jobs by 2005. K-12 enrollment has been on a steady rise and now numbers about 1,500. Since the base closure, there have been nine years of enrollment increases at NMU, and the university is considering a satellite campus at Sawyer, according to Fred Joyal, provost and vice president of academic affairs at NMU. "Things have turned out roses," Joyal said.

While there's no denying the immediate impact of the loss of thousands of jobs and families to the community, Marquette County officials and others set about the enormous task of doing something with the federal government's gift of 5,200 acres of land, dozens of airplane hangars, maintenance sheds and other large buildings, and more than 1,600 housing units, not counting 800 dormitory spaces for military personnel. And then you had the golf course and recreational facility.

"The worst part of the closing was the uncertainty of what would happen," said Bob Struck, Marquette County supervisor. And redevelopment was all the more challenging in the remote U.P., where unemployment usually runs above the national average and wages below it. But Marquette County took possession of the base and, with the multigovernmental Sawyer Base Conversion Authority, began working immediately to bring back jobs and convert the base to a civilian entity by focusing on three areas: the airfield, housing and reuse of base structures.

Making a big move

When Marquette County was handed an airport with advanced facilities, a bunch of hangars and the longest runway in the state (12,370 feet) that can accommodate any aircraft flying today, it seemed only logical to move the county's airport. While the infrastructure was partially ready for the taking, the county still had to build a passenger terminal and a service road, and make some other adjustments to bring operations in line with civilian aviation code. And while it cost the county to do all this, the opportunities for expansion and tie-ins to new businesses couldn't be overlooked.

The Marquette County Airport was rechristened Sawyer International Airport when it opened in September 1999, and since its first full year of service, total passenger traffic has increased by over 30 percent and has risen continuously after dropping in 1994 and 1995. With a passenger count of 76,670 through July, the airport is well on its way to surpassing last year's total of 115,543.

Although moving the airport was a hard sell for Marquette residents because it is an additional 15 to 25 miles away for most travelers, noise is not nor will ever likely be an issue, said Keith Kaspari, airport manager, via e-mail.

American Eagle Airlines operates one of its two major aircraft maintenance facilities at Sawyer and employs approximately 235 highly skilled technicians while also pumping $10.5 million into the local economy, Kaspari said. Many of the maintenance technicians are alumni of NMU's aviation maintenance program, Kaspari said. In addition, American Eagle opened its Aviation Maintenance Academy to train all new-hire and existing maintenance personnel from cities where American Eagle provides service. Had the Marquette County Airport not relocated to the former base, American Eagle would not have been in a position to expand its maintenance facility, Kaspari said.

In addition, said Steve Powers, Marquette County administrator, some temporary businesses have generated extra revenue for the airport—helicopter and aircraft testing, for example. One of the original businesses, Delphi Automotive Systems winter testing facility, still uses Sawyer facilities.

The airport move to Sawyer has proved beneficial in another way. The county sold the former airport land to a developer, and the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community is negotiating a deal to locate a casino there. "It's in a good location for redevelopment," said Struck, the county supervisor, who anticipates that associated businesses would add to the tax rolls.

Taking care of business

As of November, 80 businesses and government and community agencies occupied Sawyer, ranging from Potlatch Corp. to Free Will Baptist Church to child and adult day care centers; in all, they employ nearly 1,300. Sawyer's largest employers, with about 200 employees each, include Potlatch, American Eagle and ACN. According to Jeanette Maki, president and director of the Gwinn-Sawyer Area Chamber of Commerce, over half the chamber's member businesses are owned by former Sawyer Air Force people. But new additions are coming from the outside as well. In November, the Marquette County Board approved an offer from Wabash Wheel & Brake Inc. to occupy an existing facility at Sawyer. Wabash expects to create up to 250 positions over a 6-year period.

One can argue the merits of economic incentive programs, such as Michigan's Renaissance Zones, but these enticements have likely given Sawyer a leg up in the economic development race. Since Jan. 1, 2000, the former base has enjoyed "zone" status, which remains intact for 15 years. Renaissance Zones are exempt from nearly all state and local taxation on a Michigan business. Additionally, Sawyer is qualified for other federal programs, including the New Markets Tax Credit and the Small Business Administration's Hub-Zone program. It also has brownfield redevelopment opportunities, where public money often comes into play. Businesses do pay unemployment insurance, Social Security taxes, worker's compensation, sewer and water fees and property taxes resulting from local bonded indebtedness or special assessments. Businesses also pay Michigan's 6 percent sales tax.

Not all Sawyer businesses are there because of tax breaks, however. Superior Extrusion Inc., an industrial aluminum manufacturer, opened in June 1998 and received no tax abatements until Sawyer became a Renaissance Zone. Superior bought an existing building and seven acres of land and has expanded the facility twice. The company started with 20 employees and currently has 70 employees working three shifts each day about six days a week, said Randy DeBolt, marketing and sales director.

DeBolt said the company likes the location and plans to stay after Renaissance Zone benefits expire because Sawyer's "infrastructure is very good, and the workforce is strong and plentiful." DeBolt said that "it's been a wonderful location and a good reuse."

When ACN, a computer services call center, opened in 2000, it established a relationship with NMU for training purposes, according to Michael Day, director of customer care. He said that the company is rethinking the relationship, looking for new ways to attract more student workers, perhaps even establishing a campus satellite call center, partly because transporting part-time student workers to Sawyer is a challenge. Day cited a few other inconveniences with the Sawyer location, such as a lack of fast-food lunch places nearby for employees.

Many job candidates also would prefer working in the city of Marquette with its amenities, so the employee pool for his company at Sawyer is more limited. Day also cited the jump in Michigan's minimum wage this fall that, combined with high gas prices, will make it almost a wash for workers to take a fast-food job in Marquette rather than paying for gas to drive to Sawyer. Thus, ACN is looking at adjusting compensation to better compete in the job market.

Meet the new owners

At the end of June 2005, Marquette County sold 750,000 square feet of facilities and 1,000 acres of land surrounding the airport to Telkite Enterprises LLC, which renamed the area Telkite Technology Park (TTP). Telkite is also marketing 750,000 square feet of aviation-related facilities still owned by Marquette County.

Vikki Kulju, TTP's executive director, said Telkite can recruit businesses for a variety of reasons: available work force, low real estate costs, lower wages and incentives to renovate buildings. "There's a tremendous infrastructure to start with that has been improved upon by the county," Kulju said. She added that Sawyer is getting on the radar screen with bigger businesses, noting that when major aviation companies do site searches, Sawyer is on the list. "It won't be long before we land a big fish," she said.

Selling the Sawyer land and buildings to Telkite was "probably a good move," said County Supervisor Struck. "We [the county] are not marketers, and we found someone willing to take on the risk." Telkite may bring in big business, Struck said, "but right now locally owned businesses with maybe four jobs, 10 jobs, are important to keeping people in the area."

Of the 4,800 people living in the area, 3,500 live at Sawyer, which has over 1,600 housing units that include apartments, single-family homes and duplexes. When the base closed, not only were those units vacated, but a number of off-base homes, trailers and rental units lost their occupants as well.

The immediate effect was a drop in home values of 10 percent to 15 percent. But, said Scott Bammert, corporate manager of MACASU Inc., which owns 240 rental units at Sawyer, since those early days, prices have risen to market rates for the area outside Marquette and Negaunee. Powers, the county administrator, said that there didn't seem to be much of an impact on countywide housing prices when the base closed because of the distance of Sawyer from employment and service centers.

Now, fewer than 300 Sawyer units are vacant. Powers noted that 70 percent occupancy of base housing is good for the area. "It might be market saturation for the location." He added that most U.P. residents look for single-family homes rather than high-density duplex and multiplex units like those at Sawyer. According to 2000 census figures, over 67 percent of U.P. housing was single-family occupancy. And with little-to-no migration to the area, Powers said, the density of housing at Sawyer is not in much demand.

MACASU is one of the 14 housing businesses that own nearly all of the units at Sawyer, and Bammert believes that there is a demand for Sawyer housing units. He said that while most units are currently rentals, more are being sold to private owners, especially young families who are finding housing at Sawyer more affordable than in Marquette. He added that the developers meet once a month even though they are competitors. "We can't sit back and just let it happen," he said.

Shake-and-bake city

Despite the success of creating businesses and working out the governance issues, Sawyer has growing pains and suffers some of the issues that face all communities. "Sawyer has grown faster than the basic needs of a community," Bammert said.

NMU's Joyal noted that Sawyer lacks some of the traditional community amenities and that combined with the high proportion of transients living in a large number of rental properties, family and social problems are becoming more apparent. In fact, some faculty and students from NMU are working with the community organizations to address those issues.

While the ultimate goal may be to turn Sawyer into a self-governing, self-sustaining town, it's a difficult proposition. Although more and more services are coming to Sawyer, there is a shortage of day-to-day services, such as grocery stores; health services are minimal. Public services, such as policing, remain an issue, though the state has agreed to nighttime patrolling by the Michigan State Police to augment the local police force.

Struck noted that in the past five years, a community has been created, and "by U.P. standards, Sawyer is a large community." People don't have the kind of shared identity that an older town would have, Struck said. "Sawyer creates extra problems but also extra opportunities." He added that the two townships, West Branch and Forsyth, are seeing their resources stretched to support the needs of 3,500 people. Sawyer is a "shake-and-bake city," said Struck. "You stirred the pot and poured it out and you have an instant city."

Reflecting upon the decade since Sawyer closed, Powers, the county administrator, said, "The bumper sticker would read, 'We've held our own.'"

Staff Writer Joe Mahon contributed to this article.