What's the price, cost, charge or payment?

To most, this is a single, redundantly worded question. To the financial manager at a hospital, it's four different questions.

That's because health care has a financial jargon all its own to reflect the varying prices that get charged depending on (among other things) whether a patient is insured and by whom, and whether the provider is part of the plan network.

In place of price, health care has charges, costs and payments to refer to different prices and other financial matters—generating no small amount of confusion.

What's the SKU for a hernia?

The financial jargon might seem innocuous enough—if maybe tedious—to those unfamiliar with it. But it lies at the heart of pricing in today's health care system.

A "charge" refers to the retail price of a health care service for someone walking in off the street and paying cash. Providers keep what's called a chargemaster file that lists the undiscounted price for every conceivable service or product provided to patients, reportedly running to 25,000 items in large hospitals. Charges apply to very few patients—mostly those without insurance, but also those with insurance but no pre-negotiated contract for care (like workers' compensation claim filers or auto accident patients).

Hospitals and other providers are quick to note that few patients pay the full charge rate. Even for those without insurance, providers will negotiate discounts for poor patients or those unable to pay inordinately high bills—though there have been high-profile cases of hospitals aggressively going after patients with overdue bills.

Certain traditionalist groups who shun modern medicine—the Amish, for example—at times are forced to seek professional treatment in critical situations, like when an older mother has complications giving birth. Not ones for insurance, these groups often negotiate cash discounts in advance.

In a nutshell, listed charges are mostly the starting point for negotiating price discounts, often with health plans, but also for those savvy enough to ask.

"Cost" is a widely used term, usually referring to the resources (and resulting fee) necessary for a provider to offer a service—in essence, what it takes to keep the doors open. But it's also semantically misleading, because rarely does a hospital have a single "cost" for a discrete service; rather, cost is more of a benchmark price.

Cost is often invoked regarding Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, which are the fees that these federal programs pay providers—sans any negotiating—for treating their participants. Providers have long complained about reimbursements being "below cost," which means they lose money (on average) for every Medicare and Medicaid patient treated.

"Payment," finally, is simply what a health care provider receives for services rendered, whatever the original charge or negotiated discount. For operating budgets, total payments are made to align with total costs.

Who's on first? If you're still following, go to the head of the health care line because, not surprisingly, these distinctions are lost on most. "The nomenclature is still problematic. Sometimes the discussion goes past each other," said Arnold "Chip" Thomas, president of the North Dakota Healthcare Association.

Cash, check or charge?

Differentiating between charges, costs and payments might seem like mere semantics. Seeing the dollar signs hung on each might dispel that notion, because there is a large and widening spread between provider charges and average costs, or the payments that providers settle for in treating patients, particularly those with private or public health care coverage.

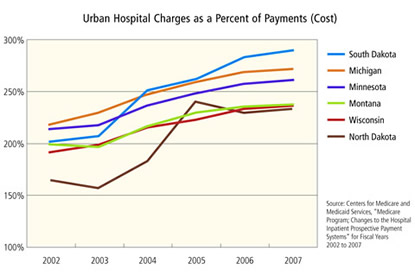

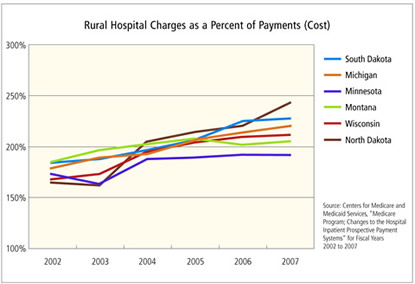

According to data from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), every state in the district saw its so-called charge-to-cost ratio increase significantly from 2002 to 2007, topping 200 percent in each state and rising in rural as well as urban hospitals (see charts below). In other words, the sticker price for a typical service was more than twice as much as the hospital received on average for that service. As recently as 1984, hospital charges nationwide were just 35 percent over payments, according to a Health Affairs article this past summer by Gerard Anderson of Johns Hopkins University.

In dollar figures, Minnesota hospitals reported charges of more than $20 billion in 2005, according to hospital data reported to the state Department of Health. But net patient revenue, after adjustments and uncollectibles, was $9.8 billion—a charge-to-cost ratio of 210 percent. The ratio swings wildly among hospitals. The top 10 ratios in Minnesota—each above 240 percent—were all in the Twin Cities metro. From there, ratios can be found at virtually every level, including two below 100 percent, meaning that original charges were lower than net patient revenue. (Both were tiny rural hospitals that likely received upward case-weighted adjustments on reimbursements for their Medicare or Medicaid patients.)

Health care providers have used the confusing terminology to occasional advantage. For example, hospitals have been making a lot of noise about skyrocketing levels of uncompensated or charity care. Those numbers could be considered inflated because undiscounted prices—charges—are typically used to calculate such costs.

But generally, hospitals and other providers are simply using this multiheaded pricing structure to help balance the books. Hospitals are low-margin businesses—just 3.1 percent for Wisconsin hospitals in 2006, according to the Wisconsin Hospital Association. How can this be, given the widening charge-to-cost ratios? It mostly relates to Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, which are typically below hospital benchmark costs. According to CMS data on common hospital and clinic procedures, Medicare charge-to-cost ratios regularly exceed 300, even 400 percent. In other words, Medicare often pays a much smaller fraction of the sticker price (or charge) than most payers.

That might sound like a good deal for taxpayers, but it has huge and cascading ramifications for privately insured and uninsured patients, driving up the prices they pay. In fact, much of today's disjointed pricing in health care can be traced to federal pricing policy for health care programs. At a deeper level, many would argue that today's pricing system is out of whack because of the broader third-party payer system that insulates most patients from the full cost of their health care consumption. But the actual mechanics of price-setting today springboard from the largest payers—in this case Medicare and Medicaid, which are infamous for reimbursing treatment below a provider's average cost.

Because many hospitals lose money treating Medicare and Medicaid patients, margins on all other patients have to increase to keep the doors open. That means charge-list prices go up; even if few patients pay the going retail price, it sets the bar higher when it comes to negotiating price discounts, whether for insured or uninsured patients.

"Does government pay their bill? No they don't. Then you have a cost shift. If government isn't paying their bills, then someone else is," said Cindy Morrison, vice president of public policy for Sanford Health in Sioux Falls, S.D.

Medicare's reimbursement system also has embedded geographic disparities—a remnant from its creation in the 1960s when policymakers wanted a reimbursement formula that was weighted for regional cost of living and a provider's fixed costs. While accounting for such factors may make sense, over time it has created a skewed pricing system that penalizes efficient, lower-cost providers—historically, those in the Upper Midwest and Great Plains—and rewards higher-cost facilities, typically in coastal states.

Recently released Medicare reimbursement data show that hospitals in district states often receive reimbursements lower than the national average. The disparity for North Dakota is particularly stark. For example, the average hospital payment nationwide for a heart valve operation in 2006 was almost $40,000, and the range of payments (from 25th to 75th percentile) was $31,000 to $43,000. In North Dakota, the range of payments for the procedure was about $26,000 to $31,000.

This payment disparity is one of the underlying drivers of a transparency initiative being spearheaded by the North Dakota Healthcare Association. "The point we're trying to make in all this is not to (just) go along with the crowd" that is pushing for greater transparency, said Thomas, the NDHA's president. Rather, the association is hoping the sunshine of transparency will help tell the world that"North Dakota has shown itself to be low cost and high quality, and we don't want to leave any doubt about cost control and health outcomes" among in-state providers, he said.

While transparent pricing will be useful to consumers, Thomas hopes it sparks conversation among federal policymakers over Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement disparities. "We're just stunned by the different payment structures depending on where the service is rendered. … So we don't find (transparency) a fearsome thing."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.