Run from the agents. Stop. Take an English class. Do community service. But don't get caught ... or you'll be deported and lose the game.

Those moves are from "ICED: I can end deportation," a new online game created by a civil rights advocacy group to help players understand the often unpredictable nature of current immigration laws and the dilemmas faced by legal and illegal immigrants in the United States.

But dealing with immigration laws isn't a game for workers or employers. And as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency—the real ICE—has demonstrated, it's not playing around either.

ICE conducted a spate of high-profile raids over the past winter and spring at Swift & Co. meatpacking plants in the Midwest, including one in Worthington, Minn., looking for undocumented workers, largely of Hispanic origin. Smaller enforcement actions continued in spring and summer in towns and at businesses throughout the Ninth District, especially in communities with food processing plants.

The raids highlight a number of issues about the Ninth District's labor force: Employers in low unemployment areas can't find enough local people to fill jobs; and there are plenty of immigrants, largely Hispanic, who will take the jobs, no matter how hard or unpleasant the work. And both are willing to take some risks.

The risk has clearly heightened. Through this fiscal year ended in July, ICE made 4,393 arrests nationwide for workforce infractions—close to a ninefold increase over fiscal year 2002, when just 510 arrests were made. While no state breakdown in those numbers is available, ICE records show that the December enforcement against Swift's Worthington plant alone netted 239 arrests. ICE made a few more arrests at Swift plants in July, largely for identity theft and document fraud.

Food fight

Though other industries are tracked, the most egregious offenses in the use of illegal immigrant labor have occurred in food processing and agriculture, said Tim Counts, ICE public information officer.

That's because these industries are in need of labor for jobs that are comparatively unattractive at prevailing (and typically low) wages. This tends to attract a disproportionate number of immigrant applicants, because skill requirements are low, language barriers are less of an obstacle, and immigrants are simply more willing to do such jobs; indeed, many have previous experience. One district poultry plant source noted that 85 percent of his company's employees are new or second-generation immigrants.

Hispanics are the largest segment of that immigrant worker population. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, a nonpartisan research organization in Washington, D.C., Hispanics accounted for 980,000 workers, or 38 percent of all workers—native or immigrant—added to the U.S. labor force between fourth quarter 2005 and fourth quarter 2006. Pew also estimates that about two-thirds of the employment increase among recently arrived Latinos in recent years "has been due to unauthorized migration." That translated to 7.2 million unauthorized Hispanics working in the United States in 2005, more than a quarter of whom worked as butchers and other meat, poultry and fish processing workers, according to Pew.

Couldn't pluck without them

Though the district has comparatively low populations of immigrants relative to elsewhere, their numbers are growing fast, in part because of good job opportunities in places with low unemployment rates and/or a strong presence in agriculture, food processing and other labor-intensive sectors paying modest wages.

A large part of the district's Hispanic population can be found toiling away in poultry and meat operations. Willmar, Minn., is home to Jennie-O Turkey Store, the second largest turkey processor in the United States, and Willmar Poultry Co., the largest turkey hatchery in the United States, and possibly the world. Both companies employ immigrant workers, some Hispanic, some Somali. Both declined to comment for this story. But Steve Renquist, economic development director of the Kandiyohi County and City of Willmar Economic Development Commission, said the city's two largest immigrant groups make the city's population 20 percent to 25 percent minority.

Renquist added that the current immigrant population "is willing to take jobs that the Anglos won't do unless they're paid significant amounts of money." Despite both employers using immigrant workers, Renquist said, there have been no mass actions by ICE in the city; only a few individuals arrested for immigration violations.

John Morrell & Co.'s largest meat processing plant is in Sioux Falls, S.D. The facility hires immigrant workers from many countries and displays the flags from those workers' countries of origin. At last count 30 different flags were hoisted outside the plant. While Hispanics may be the largest single ethnic group of immigrant workers, they do not form the overall majority, according to Dan Scott, president of the Sioux Falls Development Foundation. The company has workers "from the Sudan to Ukraine," he said.

"Legal immigrant workers have proven their value and have been an important part of the labor force, doing jobs that traditional workers won't take," Scott said. "They are filling jobs that wouldn't be filled otherwise."

Got milk (workers)?

Dairy farming is another area that increasingly relies on immigrant labor. John Rosenow, who with his partners operates Rosenholm-Wolfe Dairy in Cochrane, Wis., said there were no Mexican immigrants in Buffalo County, where his farm is located, in 1998. Today, every farmer with more than 100 milk cows has immigrant workers, and there are "maybe 100 working in Buffalo County now," he said, and "that figure could be extrapolated throughout the state."

A joint spring 2007 survey of 3,000 Wisconsin dairy producers by federal and state agricultural agencies indicated that of the 12,680 hired workers on state dairy farms, 4,220 were Spanish speakers. Enrique Figueroa, director of the Roberto Hernandez Center at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the head of the Working Group on Latino Immigrants in Rural Wisconsin that includes Rosenow, said, "If you go back five years, that number would be fairly small in our part of the world."

The same dairy survey noted that nearly 60 percent of small- and medium-size operators said that inadequate labor was a limiting factor on the future of dairy operations. "The labor situation for farmers—dairy, hog or chicken—is dire to being just about impossible," Rosenow said. Out of desperation, he added, farmers are hiring immigrants, 95 percent of them from Mexico. Rosenow shared the story of a fellow dairy farmer who is risking everything by hiring workers he believes are legal, but he can't be sure. Nonetheless, Rosenow said, if this farmer doesn't do that he can't expand his operations, which he needs to do to be competitive.

Building blocks of construction

Immigrant labor is also playing an increasingly important part in the building trades in parts of the district, reflecting national trends.

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, Hispanics took two of every three of the 559,000 new construction jobs in 2006, despite a dip in new housing starts. Although the Pew report says that the number of Hispanic construction workers decreased in the West and Midwest, Montana has seen an increase in Hispanic building trades workers.

Byron Roberts, executive director of the Montana Building Industry Association, said that finding workers is the number one industry problem, thanks to high-volume building in Montana, especially in the Bozeman area, and an unemployment rate in August of 1.8 percent in Gallatin County.

The labor problem existed before the migration of Mexican and other workers, but they have "eased the situation," he said. There are enough Hispanic workers in the building trades that safety training publications and videos are made in Spanish, he added. Of the potential that many of these workers could be undocumented, Roberts said, "It's a quiet problem."

Hispanic immigrants might also be taking a cue from ICE enforcement actions at food processing plants, shifting slowly away from some food processing jobs and into construction. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Hispanics or Latinos held 25 percent of construction jobs nationwide in 2006, compared with 15 percent of construction jobs in 2000. The BLS started tracking animal slaughtering as a job category in 2003; that year, Hispanics or Latinos held 43 percent of such jobs. Just three years later, it was 37 percent.

Tome este trabajo y ámelo (Take this job and love it)

Critics of hiring immigrant workers often point to low wages. They say if you raise wages, native workers will take those jobs. But the reality is that, particularly in low unemployment and rural areas, there are simply not enough applicants to fill demand, or the jobs themselves are unattractive—even at higher wages—evident in the fact that wages are well above minimum in some regions and industries with high immigrant populations.

Montana's Roberts said the construction jobs would go vacant without migrant workers. And pay is also going up, Roberts said, with significant salary increases and the inclusion of health and retirement benefits to retain workers. Contractors didn't do this in the past, he said, but there's competition to keep good workers.

Scott from Sioux Falls said that the idea of immigrant workers keeping wages down is not true in his city. "Unemployment is as low as it's ever been," he said, at 2.3 percent during the summer. He also noted that according to a recent survey, the city moved up from 40th to 30th place in median family income.

What's the solution?

ICE's actions may have brought some uncertainty into the business climate in the Ninth District. While raids don't have a discernible blip on the district's employment picture, certainly there's some fear of being caught up in a raid among undocumented workers and legal workers who may have undocumented family members. And employers would like to be confident that their workers are legally documented and can be relied on.

Most employers follow the current rules and regulations involved in hiring immigrant workers, but it's not an easy process (see "Playing by the rules"). And even when employers play by the rules, they can't be sure their workers have presented legal documents. One source said, "We do everything that's stipulated, but the onus is thrown back on [employers]. It's a double standard."

Of course, there will be employers who knowingly hire undocumented workers but take those chances because they need the workers and the price is right-if they don't get caught. According to Counts, ICE will prosecute employers who are in violation just as readily as it does the workers.

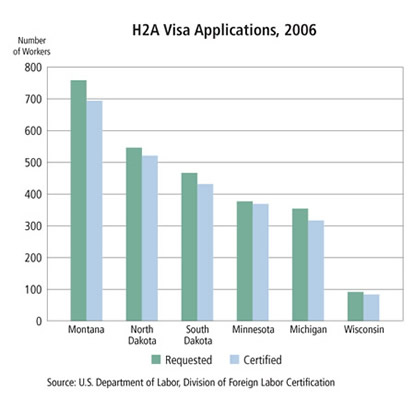

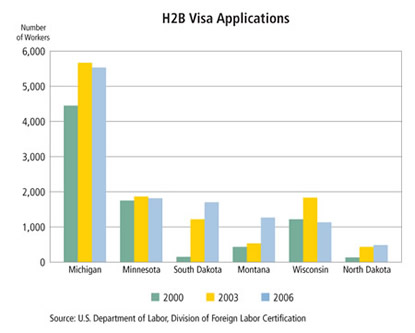

Some employers in parts of the Ninth District rely on this influx of Hispanic workers to keep their businesses afloat. Some lean on H2A and H2B visas for temporary seasonal agricultural or nonagricultural unskilled or semi-skilled workers, respectively. Data from the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) show that applications for H2B visas increased significantly from 2000 to 2006 in the Dakotas and Montana (see charts). These visas likely help get the crops harvested and the motels and restaurants staffed for summer tourists.

But employers in other industries face a dilemma when their businesses don't qualify to receive such workers, or they qualify but work visas are not issued. (The DOL certifies foreign work requests, and the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services issues the work visa itself. There is not necessarily a one-to-one match between certifications and visas, according to the DOL's Foreign Labor Certification Web site.)

More to the point about illegal immigrants, temporary work visas don't help food processing, dairy farming and manufacturing operations that run year-round and need a reliable, steady workforce. Rosenow, the Wisconsin dairy farmer, said temporary-worker visa programs are useless to him. "I need people 24 hours a day, seven days a week," he said.

The other visa program—H1B—allows longer stays, but is badly oversubscribed, and focuses on high-skill immigrants unlikely to work in those sectors.

The only solution to the issue, many say, is a comprehensive federal immigration law. Wisconsin's Figueroa supported the U.S. Senate's version of the immigration bill, however imperfect, because it would offer all players some sense of certainty. In an op-ed piece in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Figueroa noted that not only would workers' personal lives be better, but employment rules would be clearer. And employers would have a clear responsibility for their workers and would "be more likely to make business expansion decisions because labor will be more reliable and consistent."

But until then, both employers and employees must deal with the ambiguity of the current situation. And Hispanic workers, legal or not, will likely grow in numbers and importance in certain regions and industries.

"[Hispanic workers] are as important as the Chinese were to the railroads and the Irish to the mines," Montana's Roberts said.