For 50 years the telephone company in Rothsay, Minn., served as a lifeline to the wider world for residents of this small community in west central Minnesota. Omer Stowman bought the local exchange in 1946 and 10 years later used a federal program loan to upgrade switches and lines. Under President Paul Stowman, Omer's son, the firm has replaced much of its copper infrastructure with fiber optics and since 2003 has offered high-speed Internet service.

But for most of its history, Rothsay Telephone has depended on aid from larger phone companies and the government to operate and maintain its small network. Today the company derives about 30 percent of its revenue from the Universal Service Fund, a federal program that subsidizes the provision of residential phone service in rural areas. In 2006 Rothsay received almost $154,000 in universal service payments—over $300 for each of its 500 subscribers.

But for most of its history, Rothsay Telephone has depended on aid from larger phone companies and the government to operate and maintain its small network. Today the company derives about 30 percent of its revenue from the Universal Service Fund, a federal program that subsidizes the provision of residential phone service in rural areas. In 2006 Rothsay received almost $154,000 in universal service payments—over $300 for each of its 500 subscribers.

Without that support the company would be forced to more than double its phone rates to about $44 a month, Stowman said. He fears that some customers would drop their service, further eroding a customer base that has shrunk recently because of competition from wireless carriers. "We've lost some customers to cell already," he said. "We have new people moving into the area who don't even ask for phone service, and some people, if they didn't want the Internet, wouldn't bother with our phone service either."

There are scores of telephone companies like Rothsay in sparsely populated areas of the Ninth District. Despite lacking economies of scale of much larger, urban telecom vendors, rural providers typically charge much less for phone service than they spend to provide it because universal service fills in the revenue gap. The high-cost component of the USF, targeted at mostly rural areas of the country, subsidizes some telephone companies in the district to the tune of more than $1,000 per subscriber line annually.

The trouble is, the universal service system is broken. In the past eight years, USF payments, which also subsidize phone service in low-income households and high-speed Internet access in schools, libraries and rural hospitals, have increased from $3.6 billion to an estimated $6.6 billion in 2006. High-cost payouts to telecom providers accounted for over 80 percent of that surge in spending.

At the same time, consumers are migrating away from traditional, per-minute long-distance phone service, which is the funding base for the USF. Since 2000 the universal service levy on interstate and international voice traffic—which telecom companies pass on to their customers—has increased 70 percent as federal regulators try to plug the widening gap between USF contributions and expenditures.

The Federal Communications Commission, which oversees the universal service program, ruled last summer that Internet telephony vendors must also pay into the USF. FCC Chairman Kevin Martin said that tapping Internet calls was an interim measure to help sustain the fund while the agency tries to create a long-term "technology neutral" contribution system.

But increasing contributions alone won't cure what ails universal service. Deep, systemic flaws run through the high-cost program, the main subsidy vehicle for rural voice service providers. By liberally compensating phone companies—including wireless firms in recent years—for the operating costs they incur in serving rural areas, the program encourages inefficiency and undermines healthy competition in the voice market by distorting prices. As a result, telecom providers, not rural residents, derive the most benefit from the hundreds of millions of dollars that U.S. ratepayers pour into the program each year.

Robert Crandall, a telecom expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., calls the high-cost program "a pork barrel project for the owners of rural telephone companies."

The recipients of high-cost payments and some state telecom regulators counter that the program, although imperfect, is vital to public welfare in small towns and farm country. Without subsidies, how can phone service remain affordable so that people can summon the police, make a doctor's appointment or keep in touch with friends and relatives? But that defense ignores the realities of the rural telecom marketplace. Despite the price-distorting effects of universal service, robust phone competition exists in rural areas, spurred by the spread of technologies such as wireless, Internet telephony and cable phone service. In most places consumers can take their pick of a number of voice offerings, many unsubsidized.

A case can be made for cutting back or abolishing wasteful, increasingly irrelevant high-cost subsidies. There are other ways, such as refocusing universal service support on low-income subscribers, of ensuring that everyone who wants a phone can afford one.

A phone in every parlor

The practice of subsidizing rural phone service dates to the 1950s, when the original AT&T held a nationwide monopoly on telephony. With the tacit approval of the FCC, Ma Bell charged artificially high long-distance rates—primarily paid by businesses and city dwellers—in order to defray the high costs of providing local phone service in rural areas. After the breakup of AT&T in the early 1980s, hefty access charges paid by long-distance carriers to local telephone companies perpetuated these cross-subsidies.

Implicit subsidies for rural telephone service became explicit under the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which sought to foster competition in local phone markets. The universal service provision of the act states that quality phone service should be available to all Americans, regardless of location, and requires prices in rural areas to be "reasonably comparable to rates charged for similar services in urban areas."

Phone subsidies for low-income households introduced by the FCC in the 1980s became part of the USF, and the agency created new subsidies—the high-cost program and two other support mechanisms that reduce the cost of advanced telecommunications services in schools, libraries and rural health care facilities.

The high-cost program is the largest consumer of USF contributions, and the fastest growing. Nationwide, estimated high-cost support in 2006 totaled $4.1 billion, 62 percent of the overall projected USF budget and, adjusted for inflation, double the amount disbursed in 1998. (By comparison, inflation-adjusted low-income disbursements increased about 40 percent in the same period to $820 million.) The bulk of the high-cost payments went to local telephone companies and their competitors (mostly cell carriers) operating in rural service areas, defined by the FCC as those with no cities exceeding 10,000 in population.

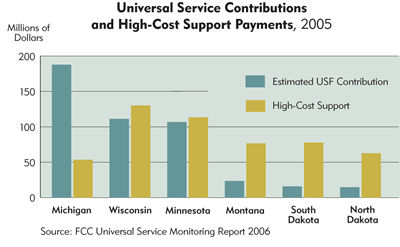

The predominantly rural Ninth District receives more high-cost payments per line than the national average and is a net consumer of subsidies. In 2005, the most recent year for which FCC estimates are available, every district state except Michigan received more high-cost dollars alone than it contributed to the entire USF (see chart). Montana phone companies received $76.7 million, more than triple the amount they paid into the fund.

Sizable annual increases in high-cost disbursements to the district mirror the national picture, according to data compiled by the Universal Service Administrative Co. (USAC), the not-for-profit entity that manages the USF for the FCC. Adjusted for inflation, high-cost payments to rural telecom providers in Minnesota and North Dakota more than doubled between 1998 and 2005; in South Dakota disbursements more than tripled during that period.

As high-cost expenditures spiral upward in the district and nationwide, they take a bigger and bigger bite out of everybody's telephone bill. To keep the USF solvent, the FCC has progressively raised the "contribution factor"—the percentage of overall interstate and international telecom revenues that flows into the fund—in this decade, although the rate fluctuates from quarter to quarter. Essentially a telecom tax, the proposed universal service levy in the first quarter of this year was 9.7 percent. All telecom companies that provide voice service beyond state borders, including long distance carriers, cell firms and local telephone companies (which are assessed a portion of their interstate access revenue) contribute to the USF. More accurately, their customers do. The universal service fee appears as a line item on phone bills.

Compounding universal service's budget squeeze, its contribution base is shrinking. A 2005 study by the Congressional Budget Office found that the USF's revenue base fell 5 percent between 2000 and 2003 as long-distance revenue declined. Tens of thousands of households have dumped traditional long distance in favor of flat-rate calling plans offered by regional telephone companies, wireless carriers and cable firms. The net result is less revenue—and USF income—per minute of long-distance calling, forcing the FCC to cast about for more funding and consider overhauling the system (see "Fixing universal service").

Gophers and idle circuits

To understand why expenditures in the high-cost USF program are ballooning, you have to delve into the Byzantine, not entirely logical design of the program.

Running a telecom company in the country tends to be more expensive than running one in a city or suburb because of lower population densities and diminished economies of scale. The high-cost program is intended to offset these operating inefficiencies, allowing voice providers in northern Minnesota and the western Dakotas to charge rates that are comparable to (and sometimes lower than) the market rate for phone service in Fargo and Minneapolis-St. Paul.

The FCC applies economic formulas to rural carriers' actual or estimated costs to determine the monthly subsidy that each company receives. Support comes in a variety of forms, each with its own cost assumptions and accounting formula. High Cost Loop (HCL) payments, meant to defray the cost of operating local lines, are based on company size (smaller telcos get more money) and the extent to which the carrier's per-line costs exceed the national average. Other types of high-cost payments include local switching support, to cover the higher per-line costs of smaller circuit switches, and Interstate Common Line Support (ICLS), created in 2001 to incorporate a portion of local exchange revenue derived from interstate access charges into the USF.

It all adds up to a substantial chunk of income for eligible telecommunications carriers (ETCs), the FCC's term for voice providers receiving universal service subsidies. High-cost payments account for as much as a third of total revenue at some rural phone companies, and per-line subsidies can run to hundreds of dollars a year. At $308 per line in high-cost support, Rothsay Telephone comes nowhere close to the district leaders in the dollars-per-line rankings. A 2005 study by Thomas Hazlett, a professor of law and economics at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., identified several rural telephone companies in the district that received high-cost payments exceeding $900 per line.

Why are such large subsidies necessary for fully built-out voice networks? "Because the cost of doing business in rural areas is tremendous," said James Groft, CEO of James Valley Telecommunications, a local cooperative based in Groton, S.D. The firm's service area covers about 2,400 square miles of farmland in the northeast corner of the state, and on average, each square mile contains only 1.7 customers. So high operating costs go with the territory, Groft said. "It costs a lot of money to maintain the network. You run into things in rural areas that you don't run into in other places." Like pocket gophers chewing through lines, 150-mile service calls and unused capacity on circuit switches.

Twelve percent of James Valley's annual revenue comes from the high-cost program. Without that money, Groft said, the price of residential phone service would jump from about $20 a month to more than $50 a month. Stowman of Rothsay Telephone echoed Groft's observations; large, attenuated networks are expensive to operate and maintain. High-cost support is vital to keep phone rates affordable for rural residents.

Inefficiency rewarded

The problem with the high-cost program is that it's really a higher-cost program. Because USF payments are made on the basis of costs—the more money an ETC spends, the more money it receives—rural carriers have no incentive to try to reduce those costs, or at least keep a lid on them. "Unfortunately, anything that is paid out in terms of costs is going to induce higher costs," Crandall of Brookings said. "[High-cost] payments reward inefficiency."

Hazlett's study found that many ETCs run up high corporate overhead expenses, which are unrelated to elevated capital infrastructure costs in sparsely populated areas. Nationally, rural telephone companies spent an average of over $98 per line on administrative expenses such as strategic planning, governance and accounting in 2005, one-third more than urban voice providers spent.

The high-cost payment system also encourages rural carriers to stay small and inefficient. By merging with another rural telephone company, or a carrier doing business in a larger town, a telco can spread its fixed costs over more customers, realizing economies of scale. And the combined company can use profits from more densely settled, lower-cost areas to offset higher line costs deep in the country. But in most cases such a strategy would be bad for business, because lowering average line costs risks making the firm ineligible for high-cost payments.

Some carriers manage to have their cake and eat it too by serving rural and urban markets under different corporate banners. James Valley, for example, has a growing, profitable subsidiary that provides unsubsidized phone service in Aberdeen without jeopardizing its parent's high-cost support for service in surrounding rural areas.

Inefficiency is abetted by lax regulatory oversight that makes it almost impossible to determine whether an individual telecom provider is spending USF subsidies on voice service as opposed to other operations—or putting the money toward shareholders' dividends. State public utilities and service commissions, which certify that carriers are eligible for high-cost subsidies, have scant authority to examine their books, even if they had the resources to do so, said Kevin O'Grady, a telecommunications analyst with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission.

"As a practical matter, with probably a hundred ETCs in Minnesota, it would take a bank full of accountants working all year to do that kind of thing," he said. "[B]arring anyone arguing that the company doesn't deserve something, we probably wouldn't look into it."

High-cost payments are in fact a general operations subsidy—funds that rural carriers can spend as they see fit, as long as they present evidence that at least some of the money is being spent on maintaining or enhancing voice service. Many rural voice carriers are highly profitable, thanks in part to universal service. Testimony in a 2004 certification case before the Montana Public Service Commission revealed that Mid-Rivers Telephone Cooperative, a rural carrier based in Miles City, Mont., regularly paid "patronage credits" to its owner-members—an average annual rebate of $200 that covered most of the cost of their phone service.

By land and by air

Traditional telephone companies such as Mid-Rivers and Rothsay Telephone aren't the only rural voice providers tapping into lucrative high-cost subsidies. In recent years wireless carriers have also become eligible for high-cost payments, creating a second, duplicative layer of subsidies that is accelerating the USF's growth and increasing the burden on U.S. ratepayers.

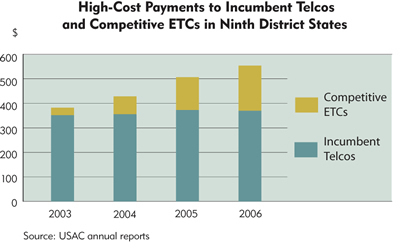

The lion's share of high-cost support goes to long-established, "incumbent" telephone companies, but the share of support going to cellular firms and other new market entrants (what the FCC calls competitive ETCs, or CETCs) has increased exponentially over the past five years.

Nationally and in the district, most of the growth in the high-cost fund since 2003 stems from payments to CETCs, according to USAC figures. CETC disbursements in district states shot up from $31.5 million in 2003 to $187 million in 2006 (see chart).

In many rural areas, the bulk of the households subscribing to USF-supported cell service have a subsidized landline as well. In essence, each household is being subsidized twice, once for a standard phone and again for wireless service that could be considered a convenience rather than a necessity. "We don't see how that's in the public interest," said Mary Wright, an attorney with the Montana Consumer Counsel, a state agency that represents consumers in utility rate cases. The counsel has opposed granting CETC status to cell carriers in the state, arguing that they should receive USF support only for customers who have no landline phone.

Current FCC practice allows CETCs to collect high-cost payments for all customers in their licensed service areas, and those payments are calculated not on the basis of their actual operating costs, but those of the incumbent telephone companies they compete with. Perversely, head-to-head competition for subscribers leads to higher subsidies; as the cell carrier takes customers away from the incumbent, that carrier's average per-line cost increases—and so do high-cost payments to both the telco and the wireless firm.

Regulators recognize the failings of this system, said Tony Clark, chairman of the North Dakota Public Service Commission. "The FCC has struggled with this one for a long time; it's been the elephant in the room that they have ignored over the years because they haven't been able to figure out what a better system would look like."

But state public utility and service commissions have readily granted CETC status to wireless firms and a few local exchange carriers and cable operators competing with incumbents. Some commissioners view USF-funded telecom expansion as a rural economic development opportunity, Wright said.

Although national wireless companies such as Verizon Communications, Sprint Nextel Corp. and T-Mobile have generally declined to apply for high-cost support, the majority of regional and local wireless providers operating in rural areas of the district are CETCs today. Many are subsidiaries of incumbent telephone companies that have long received USF subsidies for their landline business. Sagebrush Cellular, a subsidiary of Nemont Telephone Cooperative in Scobey, Mont., became eligible for high-cost support in 2005 and last year received $1.9 million in subsidies. James Valley Telecommunications plans to offer its customers wireless service next summer, through a new subsidiary that has already won CETC approval.

Time to cut the cord?

Given that the high-cost program is cumbersome, wasteful and in all likelihood unsustainable in the long term, it's fair to ask whether the time has come to give private markets freer rein in the provision of voice service in small towns and the wide open spaces in between. Should the program be eliminated, or at least curtailed, to promote increased competition and technological innovation that will improve service and drive down prices in rural markets? The weight of the evidence suggests that high-cost subsidies are hurting rather than helping the cause of universal service in most rural areas.

One justification given for universal service since its inception is that subsidies are needed to extend the voice network into rural areas, so that all Americans, not just city dwellers, can "reach out and touch someone," as ads for AT&T used to say. But decades of universal service and other federal support, such as the rural electrification grants leveraged by Omer Stowman and hundreds of other telecom pioneers to develop rural telephone exchanges, have for all practical purposes achieved that goal.

In 2005, according to FCC data, 93 percent of U.S. households had telephone service, through either a landline or a wireless account. In the district, household penetration rates exceeded 92 percent in every state; North Dakota posted the third highest in the country at over 96 percent. Moreover, those rates have changed only slightly since 1984, demonstrating that the 10-year-old high-cost program has had a negligible impact on telephone use (a small minority of households still can't afford a phone, or don't want one). Why keep subsidizing a device that can be found virtually everywhere?

Incumbent telephone companies point to the high cost of maintaining existing infrastructure, and wireless CETCs insist that continued high-cost support is needed to finance the expansion of service in areas where there aren't enough customers to pay for new base stations and cell towers. Backed by high-cost subsidies, Nemont is in the midst of a five-year build-out involving more than 20 new towers and upgrades to others in northeastern Montana and northwestern North Dakota. Extending and improving Sagebrush Cellular's coverage "absolutely would not be economically feasible without universal service support," said Nemont General Manager Shawn Hanson.

Perhaps, but that's not a strong rationale for government subsidies, unless the provision of mobile phone service is considered an individual entitlement or public good. Either argument is a tough sell, given the fact that most wireless subscribers already have a landline, or at least have access to one.

Moreover, FCC mobile phone coverage data show that cell companies were expanding their operations in rural areas of the district before a significant number of local and regional providers began receiving high-cost payments. In 2000 almost every county in the district—including sparsely populated counties in the Dakotas and eastern Montana—had at least two cellular providers. Subsequent development has just increased competition in rural service areas and filled in coverage gaps.

As for incumbent telephone companies, cost-based subsidies tend to drive up their operating costs. Abolishing or cutting back high-cost payments would force rural carriers to cut their per-line costs by trimming administrative overhead, consolidating operations with other telcos or possibly utilizing new technology to reduce maintenance.

For a growing number of rural households, subsidized landline and cell aren't the only available phone options. Regional cable firms and Internet telephony vendors are marketing voice service piped over broadband connections in many rural areas.

Cable firms such as Charter Communications and Mediacom route calls as compressed data over hybrid fiber-coaxial lines, connecting to the switched telephone network to complete calls to noncable subscribers. Voice over Internet Protocol providers stream voice data over the Internet, typically for a monthly flat rate that includes long-distance and international calls. Small communities with subscribers to Vonage, the largest of several VoIP firms operating in the district, include White Pine, Mich., Jamestown, N.D., and Shelby, Mont. As of March, the company had a total of about 51,000 customers in Minnesota, Wisconsin, the Dakotas and Montana.

None of these companies receives high-cost subsidies, with the exception of cable franchises in a few rural communities. (For more on advances in broadband telecommunications in rural areas, see "Broadband: Not quite universal.")

Researchers at the Progress & Freedom Foundation (PFF), a nonprofit institution that studies the policy implications of technological change, wrote in a 2005 report on universal service that "competitive market forces presently are providing consumers—including low-income consumers and those living in rural areas—with an array of reasonably-priced choices for voice telephone service."

Surviving sans subsidies

Basic economic theory states that government has no business interfering with healthy, competitive markets. Thirty or more years ago, when many rural households didn't have phones and there was just one type of voice service—a copper wire provided by the local exchange carrier—it probably made more sense for long-distance, mostly urban ratepayers to subsidize basic phone service in the hinterlands. But in today's rural communities, where multiple providers and technologies vie for customers, increasingly expensive high-cost payments threaten to retard rather than further the development of sophisticated, affordable voice services.

Public policy in a market economy should promote consumer choice and strive to drive the real costs of telephone service down, not up. Eliminating or phasing out high-cost support would oblige incumbent telephone companies and CETCs to reduce their costs, raise their rates or—if they truly cannot survive without government assistance—go out of business to make way for abler competitors.

In a largely unsubsidized market, telephone and cell service might become more expensive in some rural communities. There's no escaping the fact that, as a rule, providing phone service of any kind costs more in rural areas than it does in cities and larger towns. Even under the spur of competition, some carriers would have difficulty cutting enough costs to make up for the inherent inefficiency of their small, spread-out networks. However, faced with higher prices, rural residents probably wouldn't forgo phone service and cut themselves off from the world. The consensus among economists is that demand for basic telephone access is extremely insensitive to price; even if prices rose substantially, most people would still find the means to pay the phone bill. They would simply choose the best option in terms of price and quality.

Certainly higher phone rates could cause hardship for lower-income rural residents—those living on fixed incomes or in poverty. Good public policy may justify subsidizing basic phone service for people who genuinely can't afford true market prices. Economists and telecom experts who favor this approach point out that needs-based subsidies, unlike the high-cost program, would not distort prices and create false incentives for telephone companies. Nor would they furnish cheap phone service to well-off residents who can afford satellite TV, rider lawn mowers and SUVs.

That type of subsidy already exists—the universal service low-income program, which gives eligible consumers in both rural and urban areas a price break on phone service. Joseph Kraemer, a director at the Law and Economics Consulting Group in Washington, D.C., and co-author of the PFF study, said that focusing public resources on low-income subscribers is a better idea than continuing to fund the high-cost program. Low-income aid, he noted, flows directly to phone subscribers who need it and is "self-liquidating": As the income of recipients rises, they become ineligible for assistance.

The low-income program includes Lifeline support, which reduces subscribers' monthly telephone charges, and Link Up, a discount on phone installation. Subscribers whose incomes qualify them for Lifeline receive at least $7.75 off their monthly bill for either a landline or cell phone. Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan are among 26 states where low-income subscribers can apply for additional assistance from state-mandated universal service programs. Minnesota's Telephone Assistance Plan, for example, provides a monthly service credit of $1.75 on top of the federal Lifeline discount.

Another way to help low-income rural households pay for telephone service, proposed by telecom researchers at Columbia University, is to create a telecom voucher program. Residents who satisfy a means test could use their vouchers to buy market-rate telephone service from the provider of their choice.

Ironically, despite lower average incomes in many rural areas, existing USF low-income support appears to be underutilized in rural communities. Rothsay Telephone receives only about $400 per year in federal compensation for discounts granted under the low-income program. At James Valley Telecommunications only about 3 percent of the firm's customers have signed up for Lifeline, although Groft said a higher proportion could meet income requirements.

"The kind of people we have in this area, they have to be pretty hard-pressed before they apply for a program like that," he explained.Yet those same subscribers readily accept the benefits—artificially low rates—of high-cost subsidies to their local telephone company or cell carrier. Eliminating or scaling back such payments would save U.S. ratepayers billions of dollars annually and ultimately reduce the price of phone service in urban and most rural communities. But any effort to reform the system must contend with the decades-long legacy of universal service—hundreds of rural voice carriers across the nation dependent on government aid for their livelihoods.