Robert Mann used to hunt in the morning, but no longer. He looks forward to retirement—wistfully, if not immediately, despite the fact that he's 67 years old.

Robert Mann used to hunt in the morning, but no longer. He looks forward to retirement—wistfully, if not immediately, despite the fact that he's 67 years old.

Dr. Mann has a pharmacy to run.

Mann is owner of Plentywood Drug in Plentywood, Mont. He moved to the area 35 years ago and has been hard at it ever since. Mann is"interested in retiring. … I knew I was ready to quit 10 years ago." But his work schedule is going in the opposite direction, "and that's not by choice."

Leisurely hobbies like hunting have fallen away as demands on his professional time increase. The pharmacy—and often Mann himself—provides service to the local hospital and to two long-term care facilities, none of which can afford its own full-time pharmacist. Such business adds to prescription volume, but margins on the extra volume are so thin "it's hardly worth all the extra work. … We're filling more prescriptions and making less money."

Still, as a rural pharmacy owner, Mann is one of the lucky ones because it appears that he has a future buyer for his business—a rarity for many small-town pharmacies. Eight years ago, his daughter and son-in-law—both pharmacists—decided to leave their jobs at a chain pharmacy in Billings, Mont., to work at the Plentywood pharmacy and eventually take over its ownership. "If my son-in-law and daughter hadn't come home, I'm not sure what I'd be doing," Mann said.

That's not to say the future of Plentywood Drug is assured. Across the district, the retail pharmacy industry faces numerous challenges, from a pharmacist shortage to mail order competition to thinning margins and migraine headaches induced by a rise in third-party payers.

In Plentywood, the son-in-law will be assuming the major responsibilities when Mann decides to ease himself out. "I don't know where the future is. He (the son-in-law) doesn't know either. … Rightnow we're fine, but we're worried about the future," Mann said.

This might seem like a pharmacist problem—all industries have their struggles, and firms have to compete to stay open, right? But healthcare markets are unique in many ways. The connection between prescription medication and quality of life brings this issue further into people's lives than most other industries, both on a private level and on a public one, because government is intimately involved in providing access to prescription medicine.

Can't say no to drugs

Maybe ironically, uncertainty for pharmacies comes in the face of strong demand for prescription drugs and the professionals who dispense them.

According to IMS Health, a pharmaceutical marketing and research firm, the total number of prescriptions has risen from 2 billion in 1993 to an estimated 3.6 billion last year, the result of many factors, including an aging population, an expanded array of drugs and savvy marketing on the part of pharmaceutical companies. That trend is likely to hold or accelerate in the near term, thanks to a new Medicare drug entitlement program that kicked in this month to subsidize prescription drugs for U.S. seniors.

But getting your hands around the effect of increased drug demand on pharmacies and pharmacists is a tougher matter. Demand for pharmacists has increased in general, though the same cannot be said for pharmacies. Part of the analytical problem is a dearth of detailed industry data.

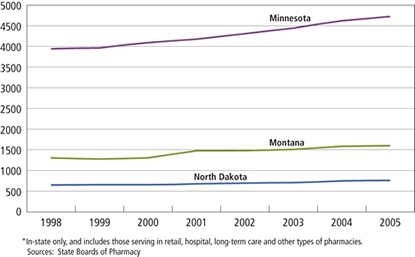

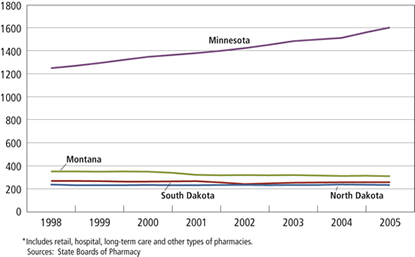

Available state-level data show that the number of pharmacists in the Ninth District has been on the rise. In Minnesota and Montana, for example, the number of licensed pharmacists practicing in all pharmacy settings (retail, hospital and other) has grown by 23 percent since 1996. North Dakota experienced 18 percent growth (see chart).

Licensed Pharmacists*, Minnesota, Montana and North Dakota

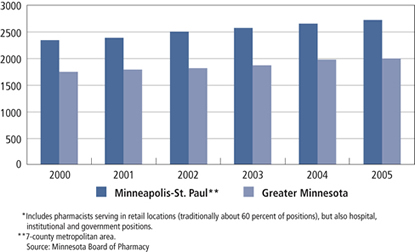

However, at least in Minnesota (which, among district states, collects by far the most detailed data on the industry), the number of retail pharmacists has grown more slowly—less than 11 percent. That's due in part to a surge of pharmacy technicians, who handle much of the prescription-filling process. From 2000 to 2005, the number of licensed techs grew 70 percent. The number of pharmacy techs in Montana almost doubled from 2001 to 2005.

Number of Pharmacists* in Minnesota

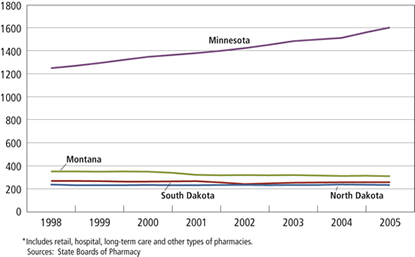

At the same time, the number of pharmacies has grown only in Minnesota and dipped in three other district states with available data (see chart). Most likely, the underlying pattern is one of growth of pharmacies and pharmacists in metros and other growing population centers, while rural areas are likely holding or even losing both.

Number of Pharmacies*, Minnesota, Montana,

South Dakota and North Dakota

Dennis Jones, executive secretary of the South Dakota State Board of Pharmacy, said that the number of pharmacists is higher, and while the number of pharmacies has "not changed a great amount … we are losing a few stores and pharmacists in rural areas and gaining more in Sioux Falls and Rapid City" as the population increases in those two cities.

In Minnesota, the number of retail pharmacies is up almost 20 percent over the last decade, to almost 1,100 last year, according to the state Board of Pharmacy. But a closer look shows a distribution pattern similar to its westerly neighbors. Since 2000, better than 70 percent of net growth in retail pharmacies has occurred in the Twin Cities. Assuming that at least some pharmacy growth has also occurred in the state's other metro regions like Rochester, St. Cloud and Duluth, the geographic tendency of new pharmacies is overwhelmingly urban.

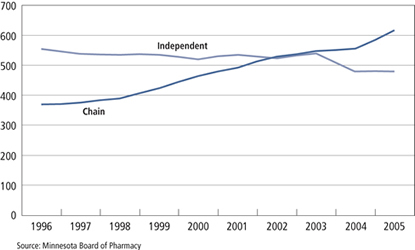

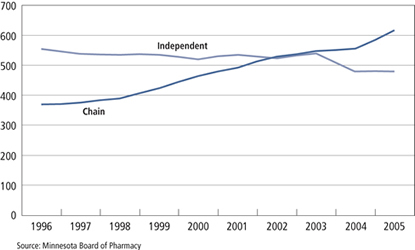

All of that pharmacy growth in Minnesota—and then some—is coming from chain pharmacies. Statewide, the number of independent pharmacies has dropped by 13 percent since 2000, while chains upped their numbers by 67 percent—a trend that generally held in both urban and rural areas, though independents held their ground better in the Twin Cities than in Greater Minnesota (see chart).

Number of Pharmacies in Minnesota

North Dakota, for one, has made sure it doesn't experience the same "chain effect" as Minnesota. State law there requires that a pharmacy be majority-controlled by a pharmacist and not a corporation, which all but prohibits chain pharmacies from entering the state. Two chain franchises (Osco Drug and Thrifty White Pharmacy) were grandfathered in when the law was passed, and their store numbers are limited.

North Dakota is the only state with such an ownership law and, not coincidentally, pharmacies in the state are overwhelmingly independent. According to a 2001 University of Minnesota study, 92 percent of North Dakota pharmacies are independent, compared with 74 percent in South Dakota and 56 percent in Minnesota.

North Dakota is the only state where none of the Target and Kmart stores have pharmacies. Last year, Wal-Mart put in its first pharmacy in a Fargo store, but did so by contracting with a local pharmacist to provide pharmacy services. The state is even home to a Walgreens—one of the largest chain drug stores in the country—with no pharmacy.

While many cheer that trend, it might not be serving consumers particularly well, because independent pharmacies are struggling to compete for reasons that go well beyond competition with chain pharmacies (and are discussed at length in other articles in this series).

Is there a (drug) doctor in the house?

As prescription drug consumption has risen, one of the challenges facing both independent and chain pharmacies is an evolving labor shortage. About a half-dozen years ago, when the economy was red-hot, pharmacists were in short supply. But that labor crunch eased with the recession in 2001.

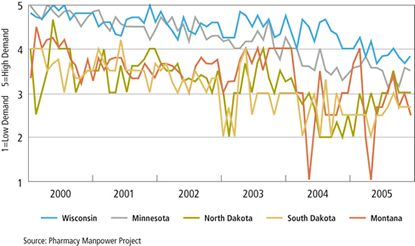

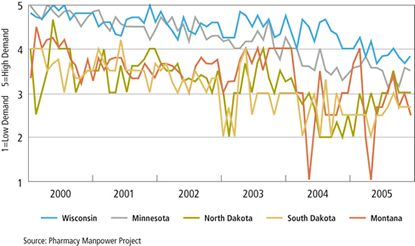

What's happened since then is a matter of interpretation. Some evidence, like the Aggregate Demand Index, suggests that pharmacist demand has trended steadily downward in district states over the past five or six years (see chart). The ADI is calculated monthly and based on a panel of industry personnel responsible for hiring pharmacists.

Aggregate Demand Index for Pharmacists

Other evidence shows the pharmacist shortage getting worse, not better, of late. The National Association of Chain Drug Stores, which represents some 37,000 such stores nationwide, calculates vacancy rates on a national basis and noted a significant cooling-off period from about August 2001 to January 2004, with pharmacist vacancies dropping by almost half, from 7,700 to 4,000. But vacancies have since bounced back up to about 6,000, or about 5 percent of all pharmacist positions in chain drug stores, as of the association's most recent survey last July. Pharmacist shortages outside of the retail sector also appear to be worsening of late but are still below peak levels of a half-dozen years ago, according to industry surveys of hospitals, health maintenance organizations and nursing homes.

Outside of a few anecdotes, not much is known about the full extent of a pharmacist demand in the district. In 2002, for example, a vacancy study by the Minnesota Office of Rural Health and Primary Care found that pharmacist vacancies were evenly split between urban and rural Minnesota. However, overall demand for pharmacists was stronger in rural Minnesota and vacancies went unfilled longer; 45 percent of rural openings were vacant for more than 10 months, compared with 25 percent for urban openings.

Several sources, including Charles Peterson, dean of the College of Pharmacy at North Dakota State University, believed the shortage today manifests itself mostly in rural areas. It's not a situation unique to pharmacies, either, as rural areas are having difficulty finding workers in virtually all health fields.

"If you would have asked me that three or four years ago, I would have given you a much different answer," Peterson said. He meets with drug and other firms that hire pharmacists, "and I've seen the level of anxiety on their face drop considerably" over the past couple of years, and firms have been "far more selective in who they hire now."

How do you spell relief?

According to a variety of sources, a bigger problem for many is finding relief pharmacists. A 2002 study of pharmacies in Minnesota and the

Dakotas found that 57 percent of rural pharmacies reported difficulty finding relief pharmacists to cover vacation, and 67 percent reported difficulty finding relief on short notice for unexpected occurrences like sickness.

More than unfilled vacancies, relief was the biggest problem in much of North Dakota, according to Patricia Hill, executive vice president of the North Dakota Pharmacists Association. "We don't have a (pharmacist) shortage like you hear in the national news." Instead, pharmacists can't find anyone to fill in temporarily if they are sick, on vacation or otherwise simply need to be out of the store—a huge drawback both for business (a pharmacy generally cannot dispense any medication without a pharmacist on the premises) and for a pharmacist's lifestyle. Hill mentioned one instance where one of her member pharmacists recently managed to take a week off for vacation—"the first time he's had a week off in two or three decades."

A chronic shortage of relief pharmacists also makes it difficult for pharmacy owners—particularly in rural areas—to find a buyer for the local pharmacy. Already, rural areas swim upstream in attracting pharmacists and other health professionals. But add work on weekends, little vacation and no sick leave to that marketing pitch, and rural pharmacy owners often find themselves with few interested takers for their business. Said Mann, from Plentywood, "Unless you're from here, you don't want to come here."

Dual studies by two University of Minnesota researchers published late last year shed some ominous light on the long-term fate of rural pharmacies. In the first study, authors Andrew Traynor and Todd Sorensen identified 126 communities of fewer than 5,000 people in Minnesota with only one community pharmacy. Among 81 owner-pharmacists responding to the survey, 26 percent expressed interest in selling their pharmacy within three years; 62 percent, within 10 years.

According to the second study by Traynor and Sorensen, there might not be a lot of takers. The study looked at ownership interests among pharmacy students in Minnesota and the Dakotas and found "limited interest in pharmacy ownership." Instead, the majority of students see themselves employed at a firm. Coupled with a rising average age among rural pharmacy owners, "many small Minnesota communities are in danger of losing local access to pharmacy services."

The study did find that a fair portion of students considered practicing in a rural setting. But an overall lack of willingness to follow through was not due to geographic concerns—being off the beaten path, as it were—but instead "from respondents' desires for a professional and personal lifestyle that may be inconsistent with the opportunities that currently exist in rural communities."

There's also a major pay gap, something that tends to be an important factor for pharmacy grads coming out of school with substantial debt. For example, pharmacy graduates from North Dakota State University's class of 2004 who took jobs at retail pharmacies in-state reported an average salary of $73,000. By comparison, graduates taking jobs in Minnesota reported average salaries of $93,000, in part because a majority relocated to the Twin Cities.

Said Hill, from North Dakota, "It's tough to keep them here when they can get 100 grand at Target (pharmacy) in Minneapolis."

Some states are creating incentive programs to help rural areas fill that financial gap. The Minnesota Legislature recently approved a program that awards eight pharmacy graduates up to $12,000 in annual reimbursement for student loan debt if they practice at a rural pharmacy. The award is good for a minimum of three years and a maximum of four years—which means a pharmacist willing to work in rural areas can slice almost $50,000 off his or her education debt. According to a state official, the program has a cap of eight awards and is already oversubscribed, having received 20 applications well before the deadline for next summer's awards.

Whether that's enough help—or the right help—to fill the need for rural pharmacists is a matter only time can predict. In some respects, time might be just the remedy for a growing pool of young pharmacists to gradually work their way to rural practices, according to Peterson, at NDSU.

After putting a lot of work and financial investment into their education, many are "looking to move away from home and earn some money," Peterson said. But after three to five years, many find themselves returning to rural areas for a higher quality of life, and the opportunity to practice what many believe is a more comprehensive model of pharmacy—getting to know clients instead of trying to reach prescription quotas.

Peterson said that 90 percent of practicing pharmacists in North Dakota are NDSU alumni, as are a high share of Minnesota pharmacists outside of the Twin Cities. Said Peterson, "What we find is that their value system changes. … Life is more than money."

Dennis Jones, executive secretary of the South Dakota State Board of Pharmacy, said that the number of pharmacists is higher, and while the number of pharmacies has "not changed a great amount … we are losing a few stores and pharmacists in rural areas and gaining more in Sioux Falls and Rapid City" as the population increases in those two cities.

In Minnesota, the number of retail pharmacies is up almost 20 percent over the last decade, to almost 1,100 last year, according to the state Board of Pharmacy. But a closer look shows a distribution pattern similar to its westerly neighbors. Since 2000, better than 70 percent of net growth in retail pharmacies has occurred in the Twin Cities. Assuming that at least some pharmacy growth has also occurred in the state's other metro regions like Rochester, St. Cloud and Duluth, the geographic tendency of new pharmacies is overwhelmingly urban.

All of that pharmacy growth in Minnesota—and then some—is coming from chain pharmacies. Statewide, the number of independent pharmacies has dropped by 13 percent since 2000, while chains upped their numbers by 67 percent—a trend that generally held in both urban and rural areas, though independents held their ground better in the Twin Cities than in Greater Minnesota (see chart).

Number of Pharmacies in Minnesota

North Dakota, for one, has made sure it doesn't experience the same "chain effect" as Minnesota. State law there requires that a pharmacy be majority-controlled by a pharmacist and not a corporation, which all but prohibits chain pharmacies from entering the state. Two chain franchises (Osco Drug and Thrifty White Pharmacy) were grandfathered in when the law was passed, and their store numbers are limited.

North Dakota is the only state with such an ownership law and, not coincidentally, pharmacies in the state are overwhelmingly independent. According to a 2001 University of Minnesota study, 92 percent of North Dakota pharmacies are independent, compared with 74 percent in South Dakota and 56 percent in Minnesota.

North Dakota is the only state where none of the Target and Kmart stores have pharmacies. Last year, Wal-Mart put in its first pharmacy in a Fargo store, but did so by contracting with a local pharmacist to provide pharmacy services. The state is even home to a Walgreens—one of the largest chain drug stores in the country—with no pharmacy.

While many cheer that trend, it might not be serving consumers particularly well, because independent pharmacies are struggling to compete for reasons that go well beyond competition with chain pharmacies (and are discussed at length in other articles in this series).

Is there a (drug) doctor in the house?

As prescription drug consumption has risen, one of the challenges facing both independent and chain pharmacies is an evolving labor shortage. About a half-dozen years ago, when the economy was red-hot, pharmacists were in short supply. But that labor crunch eased with the recession in 2001.

What's happened since then is a matter of interpretation. Some evidence, like the Aggregate Demand Index, suggests that pharmacist demand has trended steadily downward in district states over the past five or six years (see chart). The ADI is calculated monthly and based on a panel of industry personnel responsible for hiring pharmacists.

Aggregate Demand Index for Pharmacists

Other evidence shows the pharmacist shortage getting worse, not better, of late. The National Association of Chain Drug Stores, which represents some 37,000 such stores nationwide, calculates vacancy rates on a national basis and noted a significant cooling-off period from about August 2001 to January 2004, with pharmacist vacancies dropping by almost half, from 7,700 to 4,000. But vacancies have since bounced back up to about 6,000, or about 5 percent of all pharmacist positions in chain drug stores, as of the association's most recent survey last July. Pharmacist shortages outside of the retail sector also appear to be worsening of late but are still below peak levels of a half-dozen years ago, according to industry surveys of hospitals, health maintenance organizations and nursing homes.

Outside of a few anecdotes, not much is known about the full extent of a pharmacist demand in the district. In 2002, for example, a vacancy study by the Minnesota Office of Rural Health and Primary Care found that pharmacist vacancies were evenly split between urban and rural Minnesota. However, overall demand for pharmacists was stronger in rural Minnesota and vacancies went unfilled longer; 45 percent of rural openings were vacant for more than 10 months, compared with 25 percent for urban openings.

Several sources, including Charles Peterson, dean of the College of Pharmacy at North Dakota State University, believed the shortage today manifests itself mostly in rural areas. It's not a situation unique to pharmacies, either, as rural areas are having difficulty finding workers in virtually all health fields.

"If you would have asked me that three or four years ago, I would have given you a much different answer," Peterson said. He meets with drug and other firms that hire pharmacists, "and I've seen the level of anxiety on their face drop considerably" over the past couple of years, and firms have been "far more selective in who they hire now."

How do you spell relief?

According to a variety of sources, a bigger problem for many is finding relief pharmacists. A 2002 study of pharmacies in Minnesota and the Dakotas found that 57 percent of rural pharmacies reported difficulty finding relief pharmacists to cover vacation, and 67 percent reported difficulty finding relief on short notice for unexpected occurrences like sickness.

More than unfilled vacancies, relief was the biggest problem in much of North Dakota, according to Patricia Hill, executive vice president of the North Dakota Pharmacists Association. "We don't have a (pharmacist) shortage like you hear in the national news." Instead, pharmacists can't find anyone to fill in temporarily if they are sick, on vacation or otherwise simply need to be out of the store—a huge drawback both for business (a pharmacy generally cannot dispense any medication without a pharmacist on the premises) and for a pharmacist's lifestyle. Hill mentioned one instance where one of her member pharmacists recently managed to take a week off for vacation—"the first time he's had a week off in two or three decades."

A chronic shortage of relief pharmacists also makes it difficult for pharmacy owners—particularly in rural areas—to find a buyer for the local pharmacy. Already, rural areas swim upstream in attracting pharmacists and other health professionals. But add work on weekends, little vacation and no sick leave to that marketing pitch, and rural pharmacy owners often find themselves with few interested takers for their business. Said Mann, from Plentywood, "Unless you're from here, you don't want to come here."

Dual studies by two University of Minnesota researchers published late last year shed some ominous light on the long-term fate of rural pharmacies. In the first study, authors Andrew Traynor and Todd Sorensen identified 126 communities of fewer than 5,000 people in Minnesota with only one community pharmacy. Among 81 owner-pharmacists responding to the survey, 26 percent expressed interest in selling their pharmacy within three years; 62 percent, within 10 years.

According to the second study by Traynor and Sorensen, there might not be a lot of takers. The study looked at ownership interests among pharmacy students in Minnesota and the Dakotas and found "limited interest in pharmacy ownership." Instead, the majority of students see themselves employed at a firm. Coupled with a rising average age among rural pharmacy owners, "many small Minnesota communities are in danger of losing local access to pharmacy services."

The study did find that a fair portion of students considered practicing in a rural setting. But an overall lack of willingness to follow through was not due to geographic concerns—being off the beaten path, as it were—but instead "from respondents' desires for a professional and personal lifestyle that may be inconsistent with the opportunities that currently exist in rural communities."

There's also a major pay gap, something that tends to be an important factor for pharmacy grads coming out of school with substantial debt. For example, pharmacy graduates from North Dakota State University's class of 2004 who took jobs at retail pharmacies in-state reported an average salary of $73,000. By comparison, graduates taking jobs in Minnesota reported average salaries of $93,000, in part because a majority relocated to the Twin Cities.

Said Hill, from North Dakota, "It's tough to keep them here when they can get 100 grand at Target (pharmacy) in Minneapolis."

Some states are creating incentive programs to help rural areas fill that financial gap. The Minnesota Legislature recently approved a program that awards eight pharmacy graduates up to $12,000 in annual reimbursement for student loan debt if they practice at a rural pharmacy. The award is good for a minimum of three years and a maximum of four years—which means a pharmacist willing to work in rural areas can slice almost $50,000 off his or her education debt. According to a state official, the program has a cap of eight awards and is already oversubscribed, having received 20 applications well before the deadline for next summer's awards.

Whether that's enough help—or the right help—to fill the need for rural pharmacists is a matter only time can predict. In some respects, time might be just the remedy for a growing pool of young pharmacists to gradually work their way to rural practices, according to Peterson, at NDSU.

After putting a lot of work and financial investment into their education, many are "looking to move away from home and earn some money," Peterson said. But after three to five years, many find themselves returning to rural areas for a higher quality of life, and the opportunity to practice what many believe is a more comprehensive model of pharmacy—getting to know clients instead of trying to reach prescription quotas.

Peterson said that 90 percent of practicing pharmacists in North Dakota are NDSU alumni, as are a high share of Minnesota pharmacists outside of the Twin Cities. Said Peterson, "What we find is that their value system changes. … Life is more than money."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.