Mechanization has vastly increased agricultural productivity; today's farms, equipped with air-conditioned combines, heated sheds for livestock and electronic milking equipment, produce food more than twice as efficiently as farms 50 years ago. However, there's a downside to that increased productivity: increased reliance on fuel needed to run all the machinery. When energy prices rise dramatically, as they did in 2004, farmers struggle to make ends meet. But many have found a way to cope with rising prices for diesel fuel, natural gas and electricity through hedging, a financial strategy that can reduce the long-term cost of buying vital commodities.

Wheat growers in South Dakota buy the natural gas they need to dry grain months ahead, negotiating a lower price than they will probably pay on the open market at harvest time. Dairy co-ops in Minnesota also purchase their electricity and propane in advance, on forward contracts.

"Everybody is trying not to buy on the so-called spot market, so there has been a really dramatic increase in the amount of forward contracting for energy," said Bill Oemichen, president of the Minnesota Association of Cooperatives.

It's not just farmers who are hedging; more and more businesses in the district are forward contracting or using more sophisticated tools such as futures and options to exert some measure of control over what they pay for energy. The volume of energy futures contracts traded on exchanges increased 29 percent in fiscal 2005 over the preceding year, and the volume of options traded surged 49 percent, according to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (see chart).

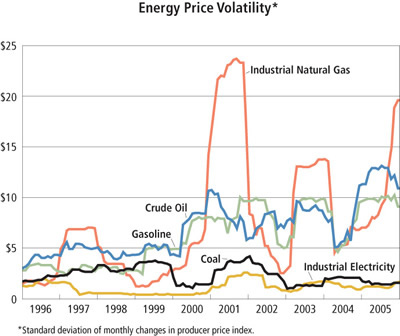

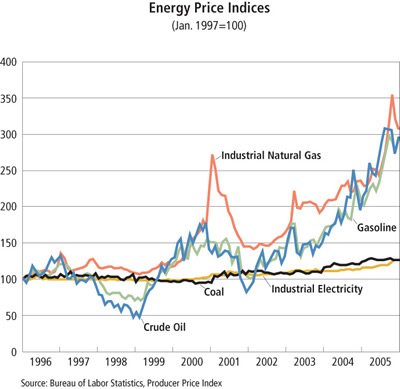

Managing fuel risks has become a matter of survival for many firms in the district and across the country. In the past three years, energy commodities such as diesel fuel, natural gas and heating oil have all nearly doubled in price, thanks partly to greater demand from rapidly growing economies like China and India. Over the same period, prices for those same commodities have swung wildly. Last year, the monthly price volatility of natural gas, for example, almost tripled from 2004.

Ballooning prices means higher operating costs for businesses—trucking firms, electric utilities and farmers, for example—that depend heavily on certain energy commodities. Rising volatility increases the risk of making future purchases.

For some businesses, blunting price spikes is simply a matter of tacking on a fuel surcharge. Trucking firms can pass along the cost of pricier diesel to their customers, and pad their earnings when they can find cheap fuel. Retail chains, supermarkets, manufacturers and other firms that ship their products by truck may or may not be able to pass higher fuel costs along to their customers, depending on competitive pressures in their industry.

Conservation is another obvious response to escalating energy prices. Factories can turn down their thermostats, and shippers can employ ever more advanced logistics technologies to reduce their wasted miles. It may also be possible for a company to switch to an alternative fuel—in effect, diversifying its energy portfolio—when the price of its standard fuel jumps. But given the constraints of today's technologies, there's a limit to how much energy a business can save, and to what extent it can shift to alternative, cheaper fuels.

Hedging—the general term for using a portfolio of forward contracts, futures and options to manage risk—is not for the faint of heart, or businesses lacking a modicum of financial savvy. The practice can be expensive and impracticable for small companies, and it carries its own risks. But for firms without other means of cushioning the impact of soaring, unpredictable energy prices, a solid hedge can offer shelter from the storm.

Weighing your options-and futures

Hedging strategy can be extremely complicated, but the basic idea is to hedge enough to protect yourself against future price increases without hedging so much that the additional costs wipe out any savings.

If an airline anticipates more expensive jet fuel, for example, it can purchase a futures contract in which it agrees to buy a certain amount of fuel at a given price on a specific date. If the market price of jet fuel soars, the airline's supplies are safely locked in at a lower price. While this strategy shields against price increases, it also entails risk: If the market price of jet fuel falls below the contract price, the airline gets stuck paying a higher price for fuel than it would have if it had bought fuel on the spot market. If the airline wants to avoid this risk—which puts it at a disadvantage to unhedged competitors—it can choose to buy an options contract.

An option gives the user the right (but not the obligation) to buy or sell a commodity—or a security such as a future—at a given price over a specified time frame. Different types of options (see sidebar) let companies cover their risks with a flexibility that futures don't permit, but that freedom comes at a price—the cost of the option, known as the option premium. An option reduces the potential loss from a fuel transaction to the option premium, if the option is allowed to expire.

To cover the bases, Airline X might buy a "put" option on the futures contract it already holds. If the spot price of jet fuel falls below the futures price, the airline can exercise the option, selling its futures for a predetermined price so that it can buy fuel at the spot price. Alternatively, if the market fuel price rises above the futures price, the airline holds onto its futures contract and lets its put option expire. The cost of peace of mind is the option premium—about 5 percent to 20 percent of the underlying price, depending on market demand for the option and the price volatility of that commodity.

The airline may also choose to purchase "call" options directly for jet fuel, securing the right to buy some of its fuel at a set price as insurance against dramatic price hikes. Depending on the needs of the airline and its managers' appetite for risk, the company selects a portfolio of instruments to best manage risk.

Futures and options are usually thought of as trading on exchanges, but a great deal of trading is less formal. "There is a very well-developed, extremely liquid over-the-counter market for trading those things, although not very visible to the untrained eye," said Chris Prouty, a commodity futures management consultant at the Minneapolis office of F.C. Stone Group, a financial consulting firm. Energy securities are part of a much larger over-the-counter derivatives market for all commodities, estimated at $1.4 trillion worldwide last summer by the Bank for International Settlements, an international central bank.

While volume is up on exchanges, not all of the activity is due to businesses hedging their risks. Increased volatility also means that speculators—investors interested in turning quick profits, not buying commodities—stand to make money trading futures and options. Such speculation is invisible because exchanges don't reveal the identity or motives of traders.

A useful benchmark for commercial hedging activity is the number of "open interest," or outstanding, contracts waiting to be settled. True hedgers hold onto fuel or futures contracts longer than speculators, anywhere from a month to several years. Most trades on exchanges are probably speculative, but the average monthly number of open interest futures contracts increased 63 percent in fiscal 2005 over the preceding year, and for options that figure nearly doubled.

Hedging against the competition

Depending on a firm's degree of exposure, how it manages energy risk can spell the difference between profitability and failure. Northwest Airlines is an example of a company that chose not to hedge against the rising costs of a vital commodity—and paid the price. Like most airlines, Northwest hedged its purchases of aviation fuel until a few years ago. But dwindling cash reserves forced the company to abandon that strategy, and when the price of jet fuel soared in late 2004, high fuel costs helped to drive Northwest into bankruptcy.

In contrast, Southwest Airlines has become the poster child for effective energy risk management and has seen its margins jump in a struggling industry. Analysts often contrast the Dallas-based discount carrier's practices with those of larger, troubled airlines such as Northwest and United. Southwest's risk management portfolio, comprising options, futures and over-the-counter instruments for fuel as well as other commodities like heating oil, not only helped stabilize the price it paid for fuel, but also generated a profit, raising the company's stock price.

Companies in other energy-dependent industries have come to recognize the upside of a well-executed hedging program. Hard data on hedging activity by district firms are scarce, but according to commodities brokerages and consultants, businesses large and small have adopted various hedging strategies in an effort to soften the blow of higher, more volatile energy prices. "I think we've seen interest from every angle," said Prouty, whose office has advised several Fortune 500 companies as well as small and medium-sized firms in the Upper Midwest.

Several large companies in the district are known for their astute management of energy risk. Agricultural titan Cargill Inc. hedges to reduce the costs of storing, transporting and processing grain all over the world. As a large chemicals producer, 3M buys oil and natural gas not only to burn, but to use in the manufacturing process. According to its annual report, the company engages in both forward contracting for fuel and commodity price swaps, deals that allow businesses to lock in prices by trading cash flows generated by fuel purchases.

The presence on the buying side of experts formerly in sales has itself stimulated more hedging activity by making firms more aware of the array of financial tools available to tame risk. Rampant speculation in energy markets in the 1990s swelled the ranks of innovative, experienced energy traders, and when the bubble burst, those experts turned their hand to risk management.

Sid Jacobson, managing consultant for the global energy practice at PA consulting in New York City, said that alumni of Enron, Williams Energy Services and other large commodities trading houses are setting up their own trading desks specializing in risk management. "I can't think of a client I walk into now where there isn't somebody that used to work at Enron running their commodity group," Jacobson said.

Jacobson added that fuel purchasing decisions have moved from the procurement department to the executive suite; just like hedging against fluctuating currency exchange rates and interest-rate increases, fuel hedging is increasingly viewed as a top-level financial strategy. "CFOs are now in charge of these decisions, as opposed to embedding it in a supply contract or something," he said.

Typically, big corporations play the hedging game close to the vest, taking care not to discuss their risk management strategies or signal their day-to-day moves in commodities and futures markets. "If someone stood in the middle of the crowd and just announced that Kellogg's was buying wheat that day, there's going to be no sellers for that buyer," said Warren West, president of Greentree Brokerage Services in Philadelphia. "And it's the same thing in the energy markets. For a large institution to go into the markets and tip their hand, it's counterproductive, so they're very good at hiding their intentions."

Small companies, big risks

It's not just the giants that are turning to financial markets to moderate energy risk. Yocum Oil in St. Paul, Minn., provides forward contracting and hedging services to a variety of smaller organizations in Minnesota and Iowa, including municipalities, manufacturers, farms and gas stations. Demand for those services has increased in the last two years, Vice President Tony Yocum said. State and local governments in particular, faced with steadily increasing fuel expenses for public vehicles and energy costs for buildings, are exploring risk management options.

"I think we're going to see a tremendous amount more focus on using risk management tools from the energy side, in [government] entities," he said.

Electric utilities have an obvious reason to hedge. "In addition to the generating resources that we own, we have a variety of purchase contracts that go anywhere from short-term daily purchase contracts to very long term," said John Brekke, vice president for member services at Great River Energy, an electricity generation and transmission cooperative based in Elk River, Minn.

Great River buys multiyear forward contracts on coal from the Powder River Basin. The price of coal has increased along with that of other fossil fuels, but the price of the North Dakota coal started to rise more recently, and not as drastically, as coal from other sources. GRE also benefits from having its flagship plant located next to the Falkirk, N.D., mine with which it contracts for coal. "When you adjust for transportation cost, we're getting the least-cost supply of coal that we can possibly achieve," said Brekke. In the past, GRE has used futures to buy natural gas for its peak-load plants, and may do so again, he said.

Most smaller businesses prefer to enter into forward contracts for their fuel, or buy futures, instead of buying call options on fuel commodities. "It just seems to be a little bit easier to understand and requires less cash up front," said Yocum.

The South Dakota Wheat Growers cooperative, for example, forward contracts for the natural gas it uses to dry grain. "At this time, we would probably protect 80 percent of our average [annual usage]," said Chief Operations Officer Richard Bentley. The challenge is guessing months before harvest how much gas to buy; the amount needed varies with the quality of the crop. In June, when the co-op signs its contracts, it's too early to tell how dry the grain will be in the fall.

To hedge or not to hedge?

While many companies have embraced the idea of hedging to manage energy risk, others have held back, leery of the potential downside of forward contracting and investing in futures and options. The inherent uncertainty of hedging can also cause a kind of paralysis, a suspension of sound judgment. Panicked by rising prices, some managers dive into hedging without formulating a sound risk management strategy, Jacobson said, while others resign themselves to paying through the nose for energy until market prices come back down. "[N]either decision seems to be right," he said.

A look at the trade-offs involved in hedging can help a business decide whether it's better to hedge, or suffer the slings and arrows of the spot market:

Degree of exposure. What financial impact does a price increase of a few cents per gallon represent, compared with other expenses? For the South Dakota Wheat Growers, fuel surcharges charged by railroads that haul its grain dwarf the co-op's expenditures on natural gas and diesel fuel—about $3 million each year, Bentley said. Wheat Growers paid $6 million in railroad surcharges last year. So the co-op is content for now to restrict its forward contracting to natural gas.

Business size. The typical future traded on exchanges is very large—42,000 gallons for a single futures contract for heating oil, for example. That may be fine for a big company, but too much to handle for a small firm, effectively excluding it from exchange markets. An alternative for small hedgers is contracting with their suppliers, or buying securities over the counter. Yocum and other providers offer ways for small users to pool their resources to buy forward contracts and futures on exchanges.

Cash or credit? Protection from uncertainty costs money, much of which must be paid upfront, taxing the liquidity of smaller businesses. A side effect of higher fuel prices is that more collateral is required to cover the increased value of forward contracts. In the options market, seesawing fuel prices have inflated premiums, although option prices have started to decline in the wake of last summer's Gulf Coast hurricanes. "You could be looking at sometimes a 30- to 40-cent premium to cap heating oil exposure one or two months out, which is pretty expensive," Prouty said. "If heating oil is only $2 a gallon, that's 25 percent of your total cash outlay just in insurance."

Risk of default. Increased volatility increases the likelihood that a fuel supplier will not deliver on the contract. If fuel prices drop drastically before a forward contract comes due, a seller may opt to breach the contract instead of taking a huge loss. "You're seeing a lot of litigation on smaller contracts," Jacobson said.

Smart hedging requires a lot more than the ability to make a ballpark estimate on where energy prices are headed. In deciding whether or not to hedge, and if so, how much to hedge and with what kind of investment portfolio, a business must consider all of the above factors and how they affect the bottom line. "If (businesses) look at these things holistically, they can make a better decision on what hedge is appropriate ... what's going to meet their objectives," Jacobson said. As the current increase in activity suggests, companies become more interested in energy hedging when market conditions turn sour. But hedging insiders stress that firms should strive to manage risk all the time, even when prices are favorable.

As a rule of thumb, Yocum recommends hedging 70 percent to 80 percent of fuel usage in some way and then hoping prices drop later. Sound counterintuitive? He explained that unhedged fuel purchases become cheaper when prices fall, and a company can always negotiate lower prices on the hedged portion when it comes time to buy forward again. If, on the other hand, prices keep rising, that's what the contract was for in the first place.

Such a long-term approach is the way to go, Prouty said; start hedging today and keep at it instead of waiting for high fuel prices to precipitate a crisis. "[That's] like buying insurance for your house after your house burns down," he said. "I think from a strategy standpoint, it's prudent to get started and stick with it over a period of time. Because it eventually will pay off, if not in direct cash, then at least in saving your business at some point."

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.