When it comes to the noble profession of teaching, one would be hard-pressed to find a more challenging setting in the Ninth District than Minneapolis.

Though test scores have been climbing, they are comparatively low. A high percentage of students come from single-parent and low-income households, and according to a December assessment by the school district, performance gaps for minority and low-income students, students with limited English proficiency and those in special education "continue to remain large." According to a district survey, only 40 percent of high school students believed that their peers respected teachers.

But after all the long days, all the hard work, year after year, at least Minneapolis teachers could depend on a stable, even comfortable retirement, right?

Right?

Yes, most likely, but you wouldn't know it if you looked at their pension piggy bank. That's because the Minneapolis Teachers' Retirement Fund (MTRF) is seriously underfunded, to the tune of almost $1 billion (yes, with a "b").

How it got so isn't tough to figure out. Actuarial calculations tell a pension plan how much it should set aside to pay future retiree benefits. Contributions to the plan from both the government employer and the employee are invested. Over time, the whole pot is expected to grow big enough to cover future retiree benefits being promised today. In the Minneapolis teachers' case, contributions have lagged, and recent investment returns have been abysmal. Although the fund has been historically underfunded, legislators haven't been afraid to improve benefits either.

That recipe for pension deficit disorder is familiar to a lot of pension funds across the nation and the Ninth District. More than 2,000 local and state public pensions across the country are staring at unfunded liabilities totaling almost $270 billion, according to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA). That's equal to the shortfall in private pensions among the Standard & Poor's 500. When private-sector workers lose their pensions, it's a spectacle—company bankruptcy, congressional hearings, public outcry and blanket media coverage.

If you haven't heard or read much about problems with local and state public pensions, it's partly because they are fundamentally different in scope. When private pensions get into trouble, retirees and current workers often lose some or all of their retirement benefits. What often happens is bankrupt companies pass their pension obligations to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., the federal agency that insures private pensions, but at a fraction of their value.

Not so with public pensions, because benefits earned are treated as entitlements—they can't be revoked—and pension plans almost always have an emergency fund—called "taxpayers"—to bail them out. As a result, problems with public pensions tend to be less immediate, less "today" and more "tomorrow."

For taxpayers, getting vested in debates over public pensions takes patience, because they quickly descend into bureaucratic, number-filled jargon. "Unfunded actuarial liability" is the essence of the problem, but that's not exactly a clarion call to public outrage and action.

But the problem of underfunded local and state pensions is widespread. The Municipal Employees' Retirement System of Michigan, a plan paying retirement benefits to about 19,000 beneficiaries, was 77 percent funded at the end of 2004. Sounds mostly funded, right? Yes, technically, except that a 23 percent shortfall translates to $1.4 billion in unfunded liabilities—money that will have to be found somehow, somewhere (more on that later).

Michigan is hardly alone. Two of Montana's largest pension plans, which cover better than 90 percent of all local and state employees, have a combined $1.5 billion in unfunded liabilities. The North Dakota Teachers' Fund for Retirement has accrued unfunded liabilities of almost $500 million; the largest single fund in Minnesota, the Public Employees Retirement Association (PERA), stared at a pension shortfall in 2005 of $4 billion, more than double the level just three years earlier.

And then there's the Minneapolis Teachers' Retirement Fund: For every dollar of benefit it expects to pay out in the future, the fund has only 46 actuarial cents. A 2003 state commission report noted that a combination of factors would likely lead the fund to become more deficient over time—which has, in fact, happened—creating "a dim picture indeed for this fund. Without early and substantial corrective legislation, this fund may face the very real possibility of running out of assets." The report remarked, literally in bold print: "legislative attention is urgently needed."

Unfunded pension liabilities are like snowballs rolled downhill; they tend to become bigger without any additional assistance. That makes playing catch-up even tougher. In Minneapolis, pension funds for city workers, police and firefighters are also badly underfunded. From 2002 to 2004, the city upped its contribution for city-worker and police funds almost sixfold ($15 million to $87 million) and also issued about $120 million in bonds to help fill the hole. Still, the three funds—fairly small in terms of membership—had a combined actuarial gap of $300 million as of 2004.

How public pensions got in this predicament takes us back to that recipe, and it's a simple one, really. In any pension plan, promises to retirees have to be equaled by contributions, plus investment gains. In every case of underfunding, there is either too much or too little of one ingredient. Fixes for some public pension funds are easy and painless—a couple of decent years in the stock market. But they are the minority, and difficult decisions lie ahead for those pensions whose retiree benefits and contributions are fundamentally mismatched.

Party like it's 1999

Rising unfunded liabilities is a recent reversal of fortune. Just a short half-decade ago, public pensions were flush, thanks to the bull stock market of the 1990s. By 2001, actuarial funding ratios (liabilities divided by assets) for 103 of the nation's largest local and state pensions, including 16 in the district, averaged 101 percent—fully funded, plus change, according to NASRA. Many of the largest public pensions in the district showed a similar healthy glow.

Then came the stock market crash, and pensions started sinking. By 2004, the big pensions saw their funding ratios decline to 88 percent. Roughly three in 10 had a funding ratio below 80 percent, a level many view as the actuarial line in the sand.

The fedgazette reviewed actuarial, investment and other data for 15 of the largest local and state pension plans in six district states. Together, these plans encompass better than 90 percent of all state and local public workers in these states. Given the most recent data on each plan (2005 for most, but 2004 for several), it appears that local and state pension funds in the district are largely following the national trend, and may be doing a bit worse than average: Funding ratios for all but two have declined since 2001, and some have fallen precipitously (see 10-year funding ratio charts and Ninth District pension fund data spreadsheet.) Forty percent have ratios below 80 percent.

Collectively, these 15 pensions had combined unfunded liabilities of $20 billion, according to the latest figures available.

(Though the focus here is on major local and state pensions, it should be noted that many smaller pensions also find themselves underfunded. Pensions for Montana state police and firefighters—both of which have around 1,000 active and retired members—had funding ratios last year of 58 percent and 64 percent, respectively.)

The travails of the stock market are the first and most obvious source of the decline. "It was the primary and only reason why we're seeing the change" in funding ratios, said Chris DeRose, director of Michigan's Office of Retirement Services, which oversees four separate pension plans. Just in 2001 and 2002, he said, "we probably lost 20 percent of the portfolio."

For the North Dakota Public Employees Retirement System (PERS), the two worst investment years "were a negative 4 and 6 percent," said Executive Director Sparb Collins. "Within the environment of those years, that's not bad."

He's right. All Minnesota pension plans saw investment losses in 2000, 2001 and 2002. The Minneapolis teachers' fund had the dubious honor of worst performance, averaging -10 percent over the period.

From a long-term perspective, however, one can't really pin too much of the pension problem on the recent stock market pullback—in fact, it's been a savior for most pensions. Rewind 50 years, and almost all pension assets were invested in U.S. bonds and other fixed-income sorts of securities. Though comparatively safe in terms of protecting assets, such a portfolio could not generate the returns necessary for pension funds to keep up with the benefits promised by generous government employers. During the 1970s, funding ratios generally hovered between 50 and 60 percent.

Slowly, pension funds started shifting more of their assets into U.S. stocks and other equities. Aligned fortuitously with the bull market of the 1980s and 1990s, pension funds made up huge ground in terms of their unfunded liabilities. By 2000, the average public pension was fully funded, with its portfolio holding about 60 percent equities, only several percentage points lower than the average private pension.

More than one fund basically rode that bull out of a major funding hole. Luther Thompson, with the Minnesota Teachers Retirement Association, said in an e-mail that $1.5 billion in unfunded liabilities in the mid-1990s was eliminated solely by investment gains.

The sweet life?

In a perverse way, however, outsized stock returns rationalized a fundamental change in the pension recipe: Benefits were regularly increased, and contributions—particularly from employers—tended to lose pace, at least among those with poor funding ratios.

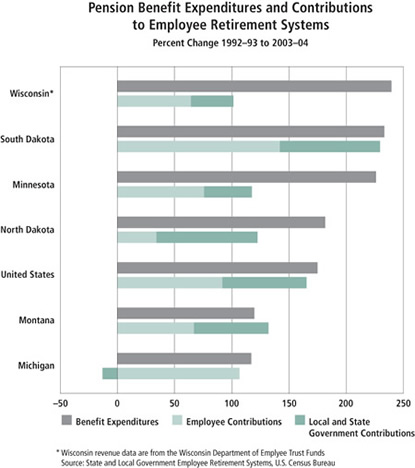

Benefit spending, in short, has exploded. Census data show that between 1992 and 2004, benefit expenditures across the country rose 175 percent. Among district states, Minnesota, South Dakota and Wisconsin all saw benefit expenditures increase by more than 225 percent during this period; Michigan and Montana had the smallest increases, both at around 120 percent (see chart).

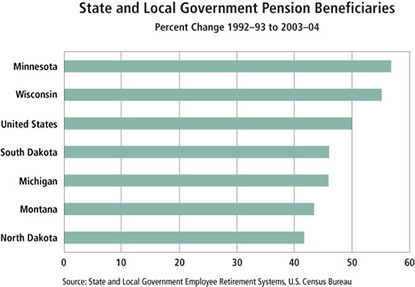

Inflation and a rising number of beneficiaries explain a relatively small chunk of the increase. The consumer price index increased 31 percent over this period, and the increase in the number of beneficiaries in individual district states ranged from 42 percent (North Dakota) to 57 percent (Minnesota).

Maybe an easier way to understand what's going on is to look at the changing relationship between average salary and pension figures. For the three largest statewide pension plans in Minnesota, the average "pension-covered" salary in 1985 was a little over $20,000 and the average annual pension for a retiree was about $5,000, according to a report last year by the Minnesota Legislative Commission on Pensions and Retirement. By 2003, the average salary was just under $37,000 (an 85 percent increase), but the average annual pension had zoomed to $18,000, a jump of about 250 percent. The rate of benefit increase is also significantly higher than the growth in contributions from either employees (85 percent) or employers (37 percent) over this period.

Retiree benefit levels have been widely deemed too generous (although the matter is not as straightforward as it might seem—see sidebar). But the blame (or credit, if you prefer) is often misdirected: Public workers, their unions and their administrators don't set benefit levels, at least in most cases. To be sure, public employee unions exert considerable lobbying and other political pressure on lawmakers to approve fatter pension and other benefits. But in the end, only state lawmakers can approve those benefit increases, and once approved, they are generally considered irrevocable. When the stock market is hot and pension assets are seemingly growing on trees, "it's very difficult to say no" to additional retirement benefits for public workers such as firefighters, police officers and teachers, said Dimitry Mindlin, a managing director with the investment firm Wilshire Associates.

Certain "yeses" also have longer liability coattails than others. For example, since 1992, Minnesota legislators have given Duluth teachers and other public employees no fewer than three bumps in the retirement multiplier, the tenure-based formula used to set a retiree's initial annuity. With the starting floor raised, additional retirement benefits further increase annuities over the course of retirement.

"In your district, I suspect the biggest benefit enhancement in the last eight to 10 years has been the cost-of-living adjustments for most (public workers) in Minnesota," said Keith Brainard, NASRA research director. These adjustments, or COLAs, provide for an annual, automatic increase in monthly pension benefits, often tied to the consumer price index, or a fraction of CPI. This might not sound like a lot, but it adds up over time and is a benefit received by few private-sector retirees.

Retirees from PERA of Minnesota receive an annual COLA equal to the rate of inflation, up to 2.5 percent, a level current retirees received on Jan. 1 of this year. Since 2002, inflationary adjustments have padded PERA retiree checks by about 10 percent; during the same period, PERA's unfunded ratio has declined from 87 percent to 75 percent.

For many plans, inflationary adjustments are not even the half of it. Most also distribute an annual boost when stock market returns are robust—often dubbed "the 13th check." During the roaring 1990s, such checks were sizable and compounded annually rather than considered a one-time bonus, creating a major stair-step effect on retiree annuities over time.

This double whammy—adjustments for excess investment returns as well as inflation—makes for eye-popping annual increases. Over the past 20 years, Minnesota's PERA pensioners have received average annual hikes of 6.3 percent, according to fund figures. And that's more the norm than the exception. From 1996 to 2002, average annual adjustments for Duluth teacher retirees were almost 7 percent.

Only three plans among the 15 largest in the district do not make automatic, annual adjustments to monthly pension checks. One is the Wisconsin Retirement System; the other two are in North Dakota, where pensioners receive ad hoc adjustments.

"If we can afford to bring (an adjustment) forward, we do it," said Collins, the head of North Dakota PERS. Until this past year, retirees had received no increase for the preceding four years, according to Collins. But things were different during the 1990s. Though ad hoc increases required the introduction of a bill during the legislative session (which itself convenes only every other year), Collins acknowledged that such bills were "fairly regular" in the 1990s.

Here's the irony and difficulty of such benefits: Minneapolis teachers receive inflationary and investment-based adjustments. When they receive both, their pension's underfunding problem can actually get worse. MTRF is required to disburse any investment returns that exceed the fund's benchmark of 8.5 percent over a five-year period. It did so frequently during the 1990s, "which means we would increase annuities" to retirees accordingly, and permanently, said Karen Kilberg, executive director of the MTRF Association. In doing so, it eliminated any counterbalance when investment returns are weak.

"It is truly a Catch-22," said Kilberg. Critics, she said, would see the large adjustments and say, "'You paid too big of a benefit increase.' Well, that was what the statute said (to pay)."

Certainly, the adjustments put retirees in the catbird seat in terms of seeing their pension checks keep ahead of inflation, plus often a little something extra for the grandkids' birthdays—sort of a "heads I win, and tails I win a lot."

In the long run, however, such benefits aren't doing pension funds any favor. As recently as 2002, the Duluth Teachers' Retirement Fund Association was fully funded. Three bad investment years have driven the pension's ratio down to 86 percent. Executive Director Jay Stoffel said via e-mail that restoring the pension to full funding is more difficult in an underfunded position, "since our annual post-retirement adjustment will continue to be paid regardless of our funded position." Simply meeting the fund's investment benchmark of 8.5 percent isn't good enough, he said. "We must exceed the assumed rate of return to improve the funding ratio."

Passing the leaky hat

Pension funds also have incentives to chase outsized investment returns—risking further losses if those investments tank—because lawmakers are not always eager to increase their contributions when pensions fall into the red.

Indeed, strong investment returns gave lawmakers the financial freedom to ease off on contributions from employees and government sponsors alike. Said Brainard, from NASRA, "We realize now that (dropping state contributions) came at a big cost."

One pension fund executive, who asked not to be named, said, "It's very easy when you want to be a hero to approve benefit increases. But it's very hard to come up with the money to pay for it."

Just ask Kilberg. She has become something of a historian to better understand how the Minneapolis teachers' fund, almost 100 years old, got to its current position. She said she's read every meeting minute available—"they had really good handwriting back then"—and every annual report and actuarial evaluation.

Her conclusion: Contribution levels to her pension have simply been too low for way too long. When the fund started in 1909, the city of Minneapolis was the fund's sponsor, but the state Legislature set the property tax levy that generated the city's contribution. "Because of legislative limits, (the fund) couldn't always get what we needed. ... We went underfunded in 1913."

Over the years, the problem has persisted. There have been periods of poor investment returns, particularly in recent years. Benefits have also increased. "It's always this or that or the other thing" that takes people's attention off the fundamental problem, Kilberg said. For a fund to remain solvent, legislators must adequately set and regularly adjust contributions according to the benefits they approve. "We are the poster child for what should not be done. ... The state didn't step to the plate the way they needed to."

In 2005, the Minneapolis teachers' pension fund saw its unfunded liabilities increase by about $120 million, mostly the residual and actuarial effects of absorbing three earlier years of negative stock market returns. Despite this shortfall, last year the fund saw employer and employee contributions fall by about 6 percent.

Kilberg has company in Minnesota. PERA's funding ratio has never topped 90 percent, and it recently slid to 75 percent. Since 1990, according to Executive Director Mary Most Vanek, total contributions have lagged behind actuarial requirements for 13 out of 15 years.

Setting contribution levels appropriately can be tricky. There's no need to over-fund pensions, and that's what would generally happen if contribution rates were not lowered when investment gains were strong. And when stock returns head south, they often coincide—as they did most recently—with hard fiscal times, when governments don't have a lot of excess cash available to quickly pump into pension contributions.

Probably not coincidentally, those pensions with the best funding ratios tend to be those where contributions kept pace. Between 2002 and 2005, the South Dakota Retirement System saw annual government contributions rise almost 40 percent to $77 million. Member contributions have risen a similar amount. As a result, the fund has managed to keep its funding ratio hovering around 97 percent since 1999.

What to do?

Public pensions have only a handful of options for dealing with actuarial shortfalls. One option—cutting benefit expenditures—is mostly off-limits.

Montana's two major public pensions, covering teachers and general local and state workers, face cumulative unfunded liabilities of $1.5 billion. The state Legislature met in special session last December, in part, to discuss a solution to the matter. Cutting pension benefits to retirees and current workers would seem to be one answer. But that politically charged option wasn't—and couldn't be—on the table.

"What our lawyers have said is they (lawmakers) can't cut benefits" because they are written into state law, said Jon Moe, a fiscal specialist with the Montana Legislative Fiscal Division. Rob Wylie of the South Dakota Retirement System agreed that retiree benefits "are extremely difficult to repeal or scale back." While there are no constitutional prohibitions to decreasing retiree benefits, "once a retiree starts a benefit, we consider that benefit to be a contractual right," he said via e-mail. Another source referred to benefits as "headless nails"—once approved, they are there to stay.

With fewer available avenues to keep pension funding ratios above water, managerial flexibility would seem critical, but as Kilberg's anecdote shows, sometimes pension managers are forced by state law to take actions they know are not in the long-term health of the pension.

The Wisconsin Retirement System is unique in that perspective. For one, contributions are not set by the Legislature, but by the system's consulting actuary with approval by a board of trustees. This means that when investment results fall short, contribution rates are increased and must be paid, according to Dave Stella, deputy secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Employee Trust Funds, corresponding via e-mail. And if a particular government doesn't feel like anteing up, contributions "can be taken from that employer's state aids," he said.

WRS also has a risk-sharing arrangement with its retirees with respect to annual adjustments. First, there is no automatic COLA or a fixed adjustment—a notable element by itself. Instead, "retirees receive adjustments only when investment experience is sufficient to fund the adjustment," Stella said. And in a logical twist that is remarkable for a public pension, "the adjustments are not guaranteed and can be taken back if investment returns are negative."

These measures go a long way toward explaining why WRS has kept its funding ratio between 94 percent and 100 percent for the better part of a decade, and has seen its ratio improve since 2000.

For those pensions that find themselves in a bigger funding hole, maybe the best strategy follows an old adage: To get out of a hole, first stop digging. To a certain extent, that's happening. Thanks to sagging funding ratios, said Brainard of NASRA, "in the last few years, any discussions of benefit enhancements have ground to a halt." Investment returns also have been generally solid the last couple of years, with many posting double-digit gains. DeRose, from Michigan, said portfolios there increased between 12 percent and 14 percent during the past three fiscal years.

But the last part—lagging contributions—is a tougher shovel to throw down, because it means government has to commit to higher annual funding. Sometimes states temporarily plug gaps with lump-sum payments. According to a 2005 pension overview by a Minnesota state commission, both Minneapolis and St. Paul teacher pensions received such state aid three times since 1993.

In Montana, the recent special session produced a lump sum of $125 million for the state's two underfunded pension funds. But now it's hurry up and wait: The Montana Legislature does not convene again until 2007. Moe, the fiscal specialist, said that proposals will come from legislators "over the next six or seven months, and bill drafts will be prepared in the months preceding the session. At this point there is no idea of what will ultimately be introduced."

Recently, probably thanks to healthier annual budgets, state legislatures have appeared willing to swallow the castor oil and make systematic changes to improve the health of pensions. In March, a state commission approved three changes for the Minnesota State Retirement System (which covers state employees): increasing contribution rates, capping annual adjustment increases and lowering benefits for those voluntarily leaving state employment. Some of these measures have also been proposed for other plans in the state; all proposals were awaiting legislative action as of fedgazette deadlines.

Such changes are boosted by the support of pension managers. Dave Bergstrom, the head of MSRS, said the pension has initiated some changes, based on the philosophy that current employees, retirees and taxpayers "should all take responsibility" for a sound pension plan.

Last year, the Minnesota Legislature approved a measure to significantly increase total employee and employer contributions to put the PERA pension, which serves local government employees and retirees, on better footing. PERA's Vanek pointed out that members received no additional benefits from their higher contributions. "Employee union leaders stepped up and agreed that it was important for the employees to help ensure the financial stability of their pension plans. The employers recognized that by waiting to adjust rates, the costs only increased, and (they) appreciate the employees' willingness to be part of the solution."

Maybe most important, the PERA board was also given the authority to incrementally adjust rates in the future as those adjustments are needed. In the past, only the Legislature could modify the pension's contribution rates, Vanek said, "which is why there were often delays in making timely rate adjustments as other budget pressures collided with the need to fund the pension plan."

Pay attention

What pension insiders seem to crave is a better understanding by the public of how the moving parts of public pensions work and interact.

"One of the things people don't understand is that ... there are no short-term fixes, but also no need to fix (a pension) in the short term," said Fay Kopp, deputy executive director for the North Dakota Retirement and Investment Office, the agency that coordinates the activities of the State Investment Board and the Teachers Fund for Retirement.

Fixating on funding ratios is too simplistic, argued NASRA's Brainard. "It's useful, but it doesn't say everything" about the long-term health of a pension, he said. Probably more important is the fiscal health and funding commitment of the sponsoring government. "It's an issue of degree ... in theory, a plan could exist at any level ... pick 90 percent. There's nothing wrong with sitting at 90 percent (of full funding) in perpetuity."

Maybe it's comforting to know that funding ratios were much lower only a few decades ago. "I've never seen any evidence that (underfunding during the 1970s) was a serious problem," said Brainard. Of course, spectacular investment returns helped rectify that problem, and there is little guarantee of returning to those halcyon days.

But Kopp thinks problems can be more easily addressed today, in part because plans are scrutinized more than they were in the 1970s. "I'm not sure how much attention there was to the issue back then," Kopp said. Today, "it's sitting here right in front of us, and we don't want to go back to where we were in the 1970s. ... We're looking at it more seriously now."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.