Poverty is inextricably linked with work—logically so, given that poverty is measured by income, and work is by far the largest contributor to people's income, particularly at low levels. By the same token, jobs are not a cure-all. Many employed people live in poverty—as attested to by nearly 50,000 working families in Minnesota alone.

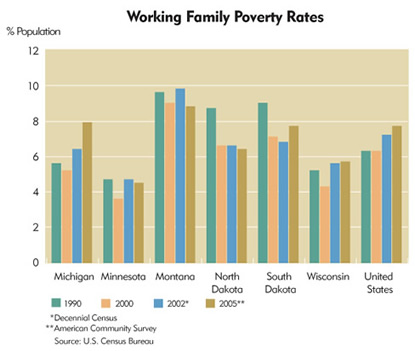

Work has a clear and positive effect on family and individual poverty: The more you work, the less likely you are to live in poverty. That was particularly true from 1990 to 2000, when the rate of working-family poverty decreased in every district state, even while it remained mostly unchanged at the national level. Still, work is not a guaranteed ticket out of poverty, particularly if you live in the Dakotas or Montana, where the working-family poverty rate runs higher than elsewhere in the district.

It might seem counterintuitive, but more working families than nonworking families live in poverty. Of the 81,000 poor Minnesota families in 2005, 60 percent had a working member. But that's because Minnesota has many more working families to begin with—80 percent of the state's 1.3 million families have a working member.

Poverty rates for families move in a logical fashion in regard to work. Poverty rates are highest for those with no working members. They decline with the presence of any working member, drop further when a member works full-time, drop further still when a second member works part time and are lowest with two working adults.

Therefore, the poverty rates for working families are significantly lower than rates for nonworking families (see chart). The worker poverty gap is even larger for families who have at least one member working year-round, full time. In the United States, only 3 percent of these families are poor, compared with nearly 20 percent of nonworking families. The poverty rate for nonworking families across the district is less than in the United States, while the poverty rate for working families is higher than the national average in the Dakotas and Montana.

Working families in the Dakotas and Montana are more likely to work part time and therefore more likely to live in poverty. This is probably due to the seasonal nature of the economy in the western portion of the district. Relying heavily on agriculture and tourism, many families are unemployed when the harvest is complete and the hunters and vacationers go home.

Though the poverty rate for district working families fell from 1990 to 2005, poverty rates fell even faster for nonworking families. During this period, the poverty rate for nonworking families in Michigan dropped from 26 percent to 16 percent. Every district state saw this rate fall by at least 5 percentage points, and into the middle to higher teens. Nationwide, it fell from 24 percent to 19 percent. The drop stems from an aging population and a growing number of households in retirement compared to working-age households that either cannot find work or choose not to work.