Are you licensed for your job? Do you feel better that your barber, electrician, dentist, lawyer, doctor, florist or horse-tooth filer is licensed? Do you even know when someone you hire is licensed, or needs to be?

If you thought that occupational licensing was a minor, boring issue in the labor market, think again. Formal occupational licensing by the states has been going on for more than a century in the United States and occurs in every state in the union. No two states (including those in the Ninth District) are the same when it comes to regulating occupations.

As the list of licensed occupations grows over time, along with the number of workers affected, licensing has major labor market implications. In the United States, more than 800 occupations are licensed in at least one state and approximately 50 are licensed in all 50 states, with thousands of laws regulating entry and "good standing" for those occupations. It's worth a look at why states license, what good (and bad) comes of it and who benefits.

Why license?

The original "public good" rationale for having government regulate certain occupations was that licensing would increase the quality of service provided while protecting consumers from incompetent and unscrupulous practitioners, at minimal costs to the state.

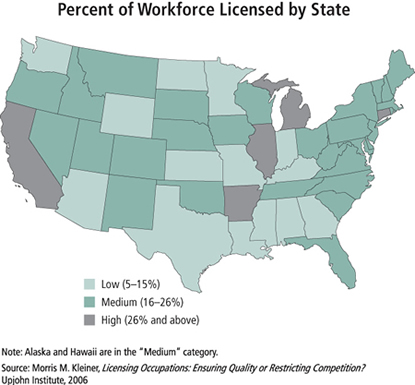

Occupations that are licensed by the states range from the familiar—dentist, doctor, lawyer—to the arcane, including crane operator, water conditioner installer and frog farmer. During the early 1950s, less than 5 percent of the U.S. labor force was covered by licensing laws at the state level. That grew to almost 18 percent by the 1980s—with an even larger number if federal, county and city licensing is included. By 2000, the share of the workforce in occupations licensed by states was at least 20 percent, according to data from the U.S. Department of Labor and the 2000 census.

Generally, less urban states have fewer regulated occupations and workers, though why that is the case is not exactly clear; perhaps simply because more populated areas tend to be more regulated in general. Among district states, Michigan and Wisconsin lead the pack with the most licensed occupations—each with more than 100—and the highest percentage of workers covered by licensing, at 28 percent and 24 percent, respectively. North Dakota ranks the lowest among district states in both the number of licensed occupations (63) and the portion of its workforce covered by licensing (12 percent; see table).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unlike other labor market institutions, like unions, which have declined significantly since the mid 1950s, licensing has benefited from growth in the service industry, where most licensing occurs. For example, licensed health care occupations such as respiratory therapist and psychologist have seen rapid job growth, as have such financial service occupations as mortgage broker and loan officer. In Minnesota, more than three-fourths of the growth in the number of licensed workers over the past decade occurred among those already licensed, such as doctors and other health care specialists.

State developments

Much like the medieval guild system in Europe that monopolized who worked, licensing in the United States has been piling on requirements and constraining entry in general. However, U.S. licensing, unlike European guilds, has evolved differently than in other countries where most regulation takes place at the national level. This is due, in part, to several important Supreme Court cases. The first, Dent v. West Virginia in 1888, established the right of states to grant licenses to protect the health, welfare or safety of citizens, and this was interpreted as giving the states the primary right to regulate occupations.

For a long period thereafter, licensing was perceived as a way for state legislatures to protect the public through the monopoly rights granted to regulate occupations. In turn, the members of the occupation were perceived as performing a public service. That policy approach to occupational regulation changed in 1975 in Goldfarb v. Virginia. Here, the Supreme Court ruled that the state bar's policy of a minimum association fee violated the Sherman Act's prohibition of monopolies in restraint of trade. Prior to the case, many state and federal courts thought that the "learned professions" should be treated differently, since their goal is to provide services necessary to the community rather than to generate profits. With this decision, occupational associations could now fall within the terms "trade and commerce" of the Sherman Act.

The central finding in the Goldfarb case was that professional licensing activities affect interstate commerce enough to trigger Sherman Act antitrust provisions. Therefore, federal agencies like the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice can sue occupations that constrain trade through unreasonable occupational licensing requirements, as well as bring greater scrutiny to the occupational policies and procedures of states. For example, federal lawsuits have been brought against dentists and those in other occupations who have sought to restrain the work of hygienists and served as a constraint on many practices of the occupations to limit supply or capture the work of other professions. The agencies argue that the monopoly impacts of licensing would have been even greater without this federal monitoring of state policies.

These court cases and general licensing growth show a subtle shift in the perceived benefits and costs. The publicly stated rationale behind licensing was to provide public protection at a time when occupational standards did not exist or were not particularly strict, and information on individuals and their businesses was tough to come by. In fact, that rationale hasn't changed much. But over time, information on occupations and their practitioners has become much more available. Because of that, the costs of licensing (restricted labor supply and higher prices) remain, whereas the apparent benefits of consumer protection are not as obvious as they once were.

Research on licensing in the late 1800s and early 1900s found that licensing provided information to consumers on minimum quality and standardization. As professional knowledge expanded in fields like health care, and as the number of available services increased in rapidly growing urban areas, consumers had little information on the quality of essential services. Licensing filled some of that informational gap on quality.

Over time, licensing activities simply branched out in terms of targeted occupations. Since early licensing was largely focused on health care and the legal professions, related occupations (such as physician's assistant and dental assistant) then became regulated during the post-World War II period. Other industries such as construction and financial services also approached state legislatures to seek regulation for occupations such as electrician and mortgage broker.

In addition, licensing has advanced laws to regulate tasks that were previously done by unregulated workers. During the last legislative session in Minnesota, horse-tooth floating dentistry became the work of only licensed veterinarians. Horse-tooth floating is the filing down of horses' teeth. Since horses in captivity no longer eat the types of food that naturally grind down their teeth, the teeth become too long for the mouth, and filing developed as an independent—and until recently, unlicensed—occupation that serves horse owners. Compromises were made to grandfather in existing unlicensed practitioners.

Not all efforts to license individual activities are successful. For example, hair braiders in Minnesota recently sued the cosmetology board for the right to do their work without coming under the restrictions of the licensing board and won.

And the payoff?

Are there measurable benefits to occupational regulation? Evidence of consumer benefits is not as obvious as one might think.

One way to measure is to compare the number of consumer complaints for a particular occupation in two states that regulate the same occupation differently. Wisconsin requires licenses for physical therapists, respiratory care providers and physician's assistants, but Minnesota only certified the same occupations during the late 1990s and early 2000s. (Certification is a lower level of occupational regulation, discussed later.) Yet no difference in consumer complaints for these occupations existed between the two states.

Medical malpractice insurance premiums also can serve as a measure of professional competence. If licensing works as intended, for example, licensed health care practitioners should make fewer mistakes (and by extension, face fewer lawsuits) relative to unlicensed practitioners. The insurance industry presumably would provide lower premiums for practitioners in regulated states because incompetent or unscrupulous practitioners would have been weeded out through higher education requirements, testing and background checks provided by licensing.

That is not necessarily the case. For example, malpractice insurance premiums for pastoral counselors, marriage and family therapists and professional counselors, who are licensed only in some states, show no difference for individuals of the same age and experience. Online quotes from insurers for typical coverage for an occupational therapist age 35 with 10 years of experience also showed no difference in malpractice insurance premiums among states that license this occupation and those that do not. At least for the insurance industry, licensing does not appear to provide sufficient benefits in reduced accidents for it to differentiate premiums.

Even in such pervasive occupations as education, the benefits of licensing are not particularly clear. Based on two detailed studies in New York and Los Angeles conducted by Thomas Kane at the Harvard Education School and other economists, there is no significant impact of teacher licensing on student achievement. The analysis found no benefits through student scores in the two cities in classes taught by fully licensed teachers versus those taught by teachers who have completed a short training program such as Teach for America or other abbreviated teacher preparation classes.

Is the price right?

Though economic benefits of licensing are difficult to identify, the costs of licensing have been easier to document. For example, licensing has been shown to dampen employment growth. For occupations regulated in some U.S. states and not in others—such as librarian, respiratory therapist, and dietitian and nutritionist—employment growth is about 20 percent greater in unregulated states from 1990 to 2000 using estimates derived from census data.

Restrictions on occupational entry come from numerous sources, but licensing can play a large role. For example, members of the occupation often dominate licensing boards. When this happens, entry requirements tend to tighten, which restricts the available labor supply. In turn, prices for these licensed services rise, and earnings for licensed practitioners go up. For consumers who can afford licensed services, quality also rises. But for lower-income consumers, the price increase means that they have no services or must turn to home remedies or hire unregulated practitioners of the services, which may be illegal.

Those in licensed occupations also tend to defend their turf. For example, dental hygienists have sought to practice without the supervision of a licensed dentist, but dentists have lobbied extensively for restraints on the ability of hygienists to practice alone or even to whiten teeth without the presence of a licensed dentist. Not to be outdone, dental hygienists are seeking legal restraints on what type of work unlicensed dental assistants can do within a dental office, since they often do the tasks of regulated hygienists.

Basic economic theory says that wages are dictated by labor supply and demand. As such, jobs with restricted entry are likely to see higher wages—a phenomenon that is clearly evident with licensed occupations.

States began regulating doctors and dentists more than a hundred years ago. Research by Milton Friedman and Simon Kuznets, two prominent economists who went on to win the Nobel Prize, found that dentists allowed more people into the occupation, while doctors restricted the supply of new practitioners by limiting positions in medical schools. The consequence was a much more rapid growth in the earnings of doctors relative to dentists during the early part of the 20th century. Estimates developed nationally using U.S. Census Bureau and National Longitudinal Survey data for 1990 and 2000 for more than 50 occupations show that between 4 percent and 17 percent of the difference is attributed to licensing, based on the occupation and time period examined. These costs of restricted entry and the induced wage inflation are ultimately borne by consumers. Estimates developed by the Minnesota legislative auditor showed total reallocation of earnings from consumers to regulated practitioners in Minnesota of $3 billion to $3.6 billion relative to the costs of having no occupational licensing. Also calculated was the total loss in state consumption expenditures using the national median elasticity of labor demand and projected consumption output losses in Minnesota's economy of $901 million to $1.1 billion for 2003.

That might seem like a lot, but it's not. It is less than one-tenth of 1 percent of Minnesota's total consumption expenditures. This helps explain why licensing continues to grow. Average consumers do not often see or feel that price inflation directly; even when they do, as individual consumers, they have little power to do much about it in a policy sense. But for professional associations and their workers affected by occupational licensing—a much more concentrated group of "winners"—wage premiums provide a clear incentive to be active lobbyists in state capitals across the country.

Policy options for the states

A common refrain heard from the public upon the discussion of policy alternatives to licensing is that "I would never go to an unlicensed fill-in-the-blank." Licensing has evolved as the preferred way to ensure service quality.

The downside is that once codified in law, licensed occupations tend to become more restrictive over time. Once an occupation becomes licensed, there are no examples from officials at the Council on Licensure Enforcement and Regulation of occupations becoming less regulated. If consumers have a high level of "loss aversion" relative to potential gains, then having a policy such as licensing may be optimal to avoid perceived negative consequences of using unlicensed labor.

Some states have been fighting the larger trend. For example, Minnesota passed "sunrise legislation" in 1976 that required proponents of new occupational restrictions to demonstrate that regulation serves the "public interest." As such, Minnesota is generally perceived as tougher on organizations seeking new occupational regulations. Related "sunset legislation" also eliminates regulation or puts time limits on regulatory processes, including licensing. Given the growth of licensing in the state, it has not delivered on past promises and has never been a regular part of the political process in Minnesota. Still, fewer individuals are regulated in Minnesota than in Wisconsin, a state with a similar population and economic characteristics.

Other regulatory options exist, including weaker forms of regulation that would provide "consumer confidence" benefits, but with fewer entry restrictions on an occupation. For example, certification is a less restrictive form of regulation in which states grant so-called right to title protection to people meeting predetermined standards. Those without certification—say, loan officers—may perform the duties of the occupation but may not use the title. An even less restrictive form of regulation is registration, which usually requires individuals to file their names, addresses and qualifications with a government agency before practicing the occupation. Registration often includes posting a bond or filing a fee.

Certification is now the second-largest form of occupational regulation in the United States, with more than 200 occupations being certified by at least one state. This mode of regulation maintains the incentives for individuals to invest in human capital but allows for substitute services if consumers perceive the prices rising relative to what they want. In addition, it provides a monitor, the government, to police those in the occupation who may not have the appropriate credentials to call themselves "certified."

Unlike under licensing, however, work can be performed by uncertified individuals, who typically do so at a lower cost. This gives consumers greater choice, and if the limited case study evidence in Minnesota and Wisconsin can be generalized, the less stringent form of regulation provides the same assurance of quality but may keep prices of services lower than do the tighter barriers to entry imposed by licensing.

Other efforts from the inside might also return licensing to its consumer-protection proclamations. The late Benjamin Shimberg, one of the first researchers to focus on the policy impacts of licensing, suggested some low-cost sunshine: Publicize complaints to and disciplinary actions taken by licensing boards.

Shimberg also suggested that licensing boards mirror boards of directors at public universities, which have only public members and generally no faculty to oversee the activities of the enterprises. In the same way, licensing boards would have only public citizens, with members of the profession advising the board on technical and other occupational issues. Providing additional public involvement to monitor and control licensing may be a political alternative to less stringent forms of regulation.

Morris M. Kleiner is a professor of public policy at the Humphrey Institute and Industrial Relations Center, University of Minnesota; a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research; and a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Kleiner is the author of a recently published book, Licensing Occupations: Enhancing Quality or Restricting Competition? Upjohn Institute, 2006.