See if you can connect the labor trend dots among a sample of business and economic development professionals across the district:

In the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (U.P.), "The only labor area that was short [before the recession] and still is, is with skilled machinist-type people."

In Rice Lake, Wis., employers need "welders, CNC [computer numerical control] operators, die cast operators, machinists, steel fabricators, lathe operators and maintenance mechanics."

In Hutchinson, Minn., "Many businesses are having a difficult time finding welders, machinists and machine operators." Need more hints? |

See also: |

In Mitchell, S.D., "In highly skilled metal fabrication, we are expecting moderate to high levels of labor shortages."

In Pierre, S.D., "Shortages are typically in the trades and construction areas with several large commercial building and highway projects under way. Heavy equipment operators are in high demand ... [and are] the most critical shortage, followed by general trades and construction workers."

In Williston, N.D., "We see a serious shortage of individuals with special skills-carpentry, masons, concrete finishers, truck drivers with CDLs (certified driver's license)."

And finally, in Billings, Mont., where "trucking and skilled labor might be showing the most signs of a shortage."

The pattern, of course—if these anecdotes aren't a good enough two-by-four over the head—is that many areas of the district are seeing labor shortages in skilled trades.

Skilled trades encompass a broad range of occupations, from construction (carpenter, plumber, electrician, heavy equipment operator, among others) to manufacturing (drafter, machinist, tool and die maker), plant and engine maintenance (mechanic, pipe fitter, welder), power or utility trades (line worker, meter repair), graphic arts (lithographer, press operator) and a variety of services (cosmetologist, painter and auto repair). Within these fields are literally hundreds of additional occupations. Wages vary by location, experience and the particular occupation, but the majority of these jobs pay $13 an hour or more, often much more.

What's ironic about this trend are the loud and persistent complaints from worker advocacy groups about the lack of good-paying jobs. It draws a mental picture of two people yelling past each other for help.

And if current trends are any indicator, cities or companies not needing skilled workers might want to take heed. Various demographic and social forces suggest that while good-paying skilled trades careers are available, workers are not putting on the hard hat, picking up the hammer or getting under the hood, so to speak, in numbers proportional to demand. Unfilled job openings make that immediately obvious.

More ominous is the fact that very few sources see an adequate supply of trainees—tomorrow's skilled trades workers. Among the existing skilled trades workforce in Montana, the leading edge is only five or six years away from retiring "and we're not replacing them as fast as they are probably going to go out," said Mark Maki, supervisor of Montana's Apprenticeship and Training Program.

When it comes to electricians in Minnesota, "generally right now there is not a shortage," said John Ploetz of the Minnesota Electrical Association, responding via e-mail. "Long term, however, we see a shortage of electricians" because the average age in the profession continues to rise, and more electricians are retiring than there are new ones to replace them, according to Ploetz. "There are not enough electricians in the pipeline."

Manufacturing a shortage

When people think of manufacturing, many perceive a dying industry because of massive layoffs. And it's true that manufacturing employment might never regain levels seen before the recession. But contrary to popular fretting, many manufacturing firms are still hiring.

Minnesota manufacturers added 2,700 to their payrolls in October alone. A second quarter survey by the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development found that 31 percent of manufacturing firms expected to add employees in the coming months, while 9 percent planned to drop workers. Through the first nine months of 2004, Minnesota and Wisconsin added about 25,000 manufacturing jobs, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Certainly, that's a far cry from the 130,000 manufacturing jobs lost in the two states roughly from 2001 to the start of 2004. But there are a lot of structural changes being made in response to tougher competition. Manufacturers "are laying off certain skill areas and yet hiring people with a higher set of skills," said Bruce Steuernagel, a labor market analyst with Minnesota State Colleges and Universities (MnSCU). Nonetheless, he pointed out, manufacturing-based programs at technical colleges "have had significant enrollment declines."

A May 2003 survey by the National Association of Manufacturers—published in the midst of profound layoffs in manufacturing—showed that 80 percent of responding employers "reported a moderate to serious shortage of qualified job applicants." More locally, Wisconsin manufacturers participating in focus groups this past summer expressed "a growing sense of concern about the lack of available worker skills to employ new technologies and process improvements."

Randy Peterson called the shortage of skilled machinists "a serious issue." Peterson is the general manager of Precision Edge Surgical Products in Sault Ste. Marie, in the U.P., and also a member of Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank's board of directors. "We could easily double our size in two years if I had enough skilled labor. So we're forced to grow only as fast as we can hire and train folks, which typically can take up to five years for someone to be productive in our higher technology areas. I do not see this improving much in the next several years."

Broken pipeline

The way into many high-skill manufacturing and other skilled trades jobs is usually through significant on-the-job training, and often formal apprenticeship certification, which is a three- to five-year contract between an employer and a student-worker. Apprentices work full time under the tutelage of other certified journeymen (the title one earns after completing an apprenticeship) and get paid a fraction of the average journeyman's wage in that occupation, usually about 50 percent or less the first year. Apprentices are also required to log 144 hours of classroom work a year on average.

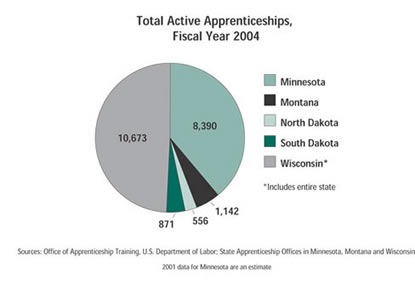

Available data on apprenticeships show this pipeline is not empty, but neither is it brimming, particularly in light of aging workforces in many skilled trades occupations. Over the past few years, apprenticeships have been trending downward (see chart). Sources say that's normal; because apprenticeships are work-based, employers are less willing to sponsor (and pay) an apprentice when business is slow. Certain sectors, like commercial construction, also tend to lag the rest of the economy both into and out of recessions because projects are often in the works for years, and apprenticeship levels seem to follow in step.

Sources: Office of Apprenticeship Training; U.S. Department of Labor;

State Apprenticeship Offices in Minnesota, Montana and Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Bureau of Apprenticeship Standards tracks apprenticeships among three major occupational categories: construction, industrial and service. Apprenticeships have declined noticeably since 2002, particularly among industrial occupations. But given the downturn in manufacturing, this also falls in line generally with the argument that apprenticeships follow industry health and activity (see chart).

Sources: Bureau of Apprenticeship Standards,

Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development

And in the bigger picture, apprenticeship trends appear positive; annual apprenticeships in Wisconsin almost doubled between 1990 and the enrollment peak of 2002. In Montana, apprentices have doubled since 1991, according to Maki, from Montana's apprenticeship program, while active sponsors (or participating employers) and completions have all been steadily rising since 1998.

Say when

Technical colleges also offer some insights into the skilled trades pipeline. Apprentices, for example, take a majority of required classroom instruction through public technical colleges (credits then can also be applied toward an academic award or degree), according to several sources. Tech schools also train many nonapprentices looking for employment in the various fields without formal apprenticeships.

Nationwide, academic awards earned in construction trades (an umbrella category covering building, industrial, repair, printing and numerous other trade occupations) have been jumpy—down from 2000 to 2002, but up considerably over 1998, according to data provided by the National Center for Education Statistics (see chart).

Sources: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education

Evidence from district states shows that manufacturing and other industrial occupations appear to be suffering the most. In North Dakota, the number of completions in skilled trades programs (two years or less) declined from 1999 to 2003, according to annual completion reports published by the university system. Much of the decline was in mechanic and repairer programs, though completions in precision production programs also dropped; completions in construction programs grew modestly. (see chart).

Source: Annual Reports, 1999 to 2003, North Dakota University System

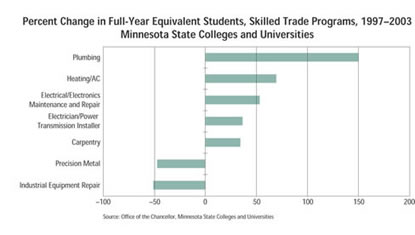

In Minnesota, enrollments in construction-based programs (like carpentry and plumbing) at two-year tech colleges have had healthy increases, while enrollments in manufacturing programs have declined, according to data provided by MnSCU (see chart).

Manufacturing firms in north-central Minnesota are voicing some concerns, according to Lisa Paxton, CEO of the Brainerd Lakes Area Chambers of Commerce. "Our manufacturers want to spend time recruiting students for these professions because they believe a [skilled worker] shortage is coming," Paxton said in an e-mail. The local Staples Technical College is known for its machine trades program, she said, yet "has only 15 students vs. highs [of] over 100 students in years past."

The red, green or blue wire?

Unfortunately, almost regardless of apprenticeship and tech education trends, putting together a neat little matrix of supply and demand for workers in skilled trades isn't so very black and white.

For one, labor markets are mobile and flexible, and workers tend to flow where the work is. So regardless of apprenticeship levels and higher education awards in a particular state or region, it's still possible for employers to find enough qualified workers, though they might have to work harder or pay more to locate and attract them.

But if every state lacks such workers, sooner or later Paul will have no Peter to rob. States regularly project future employment levels, and projected demand for many skilled trades occupations in district states is expected to far outstrip supply. For example, through 2012, Montana expects to have more than 125 annual openings for electricians and 90 for plumbing-type occupations, according to a state Department of Labor and Industry database. Annual apprenticeship completions, on the other hand, have been running about half that level over the last six years.

Wisconsin expects to see 1,000 annual openings for carpenters through 2012. But from October 2003 to September 2004, just one-fifth that number completed carpentry apprenticeships.

But not all skilled trade occupations require apprenticeship or other certified training to get a job or to find regular work—that's why you can find a half-dozen carpenters in any small-town phone book willing to bang boards for you.

"Here's a hammer and a nail and a board; it's not that difficult," said Wayne Belanger, director of education for Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC) of Wisconsin, which manages almost 1,400 apprentices in 14 different trades. This leads many self-titled carpenters to start a business out of the back of their pickup truck.

Other skilled trades, like electrical or welding, are more likely to see higher levels of formal training whether a state requires it or not. Let's just say there are certain disincentives. For example, wiring a breaker panel is a tricky task for the untrained, Belanger said, "and by the way, if you do it wrong, you're going to die."

Just one more question

Still, none of this quite explains the "why" of this phenomenon: Why are skilled trades jobs going begging when unemployment still lingers above the levels of a few years ago? Why, given persistent complaints about the dearth of good-paying jobs, are unemployed workers and those earning meager wages not standing in line for these jobs?

The reasons, it seems, are many; their underlying sources, equally numerous. For example, union critics charge that skilled trades unions try to keep a lid on apprenticeship levels in order to maintain high labor demand, which keeps wages high. On the flip side, unions point out that employers have an incentive to abuse the apprenticeship system for cheap labor because apprentices do high-skill work for a fraction of the journeyman cost. Some pointed the finger at apathetic workers. Anyone who says there aren't enough good jobs available, said a South Dakota source, "is the person who wants you to hand them the dang job, like we owe them something."

More broadly, there are obstacles preventing both employers and workers from making the training investment in a skilled trade. Said Belanger, from ABC of Wisconsin, "It's very hard to put someone in the pipeline" because it's a long-term investment. For the company, there's a commitment to paying an apprentice while they train on-site and go to school, knowing full well that the company might not gain a lifelong worker. For an apprentice—say in plumbing—"it takes five years just to take the test, and there's no guarantee you'll pass the test," Belanger said.

Maki, from the Montana apprenticeship office, said that an average apprenticeship costs a firm roughly $50,000 when you include things like work time lost by journeymen who supervise an apprentice, and it takes about three years after apprenticeship completion for the company to recoup that expense. Still, Maki believed employers are at least partially culpable for the current situation.

"I don't have employers lined up on my doorstop. [Some employers] are not willing to make the investment to train," preferring to leave that task to technical colleges, and having students rather than companies foot the bill for the training. Oftentimes when a company needs workers, "they'd rather pay more to take a worker from someone else," said Maki, who is also a second-term president of the National Association of State and Territorial Apprenticeship Directors and sits on a 30-person committee advising the federal Department of Labor on workforce development issues.

Karen Morgan, director of the Wisconsin Bureau of Apprenticeship Standards, agreed that if firms need more skilled labor, then employers are ultimately responsible for getting the necessary people into apprenticeship training. The economy and the cumulative decisions of employers "really drive apprenticeships in this state." She said that employers understand their own short- and long-term labor needs, but added, "how well they react to [those needs] I'm not sure. ... We can't take 500 people and put them in a school and turn out 500 journeymen."

Since 2000, apprentices in manufacturing and other industrial trades have declined by 40 percent in the state, Morgan pointed out, due mostly to a slow leakage in manufacturing activity as some plants close and go overseas, while remaining firms are reluctant to make investments in high-skill labor they might not need. Manufacturing and other firms are graduating their apprentices "and not putting new apprentices in the program," said Morgan. She mentioned that a major papermaker in central Wisconsin used to have 150 apprentices registered annually with the state. After being sold to a European firm, and coupled with a steep decline in the industry over the past few years, the company currently has no registered apprentices, according to Morgan.

Nor is this the first time manufacturers have circled the apprenticeship wagons, according to Morgan. During the recession of the 1980s, she said, state manufacturers cut back on their apprenticeships and it hurt them in the booming 1990s when they were scrambling for skilled labor in the face of very strong demand.

That cycle may well be repeating itself because manufacturing activity and employment in Wisconsin have seen solid growth in 2004. "They are not looking and planning for the future workforce," Morgan said. Apprenticeships with construction firms, on the other hand, "have remained fairly stable. They are always looking to the future to get ready for that next big upturn," Morgan said.

It's good work (for someone else)

District sources also pointed to a much bigger, and seemingly more entrenched, problem facing the skilled trades: poor public perception.

"The word 'apprenticeship' is kind of like the word 'vocational'; it's a bad word," said Steven Rounds, project manager for tech prep programs with the South Dakota Department of Education. "If your kid is in a vocational career, he's looked down on."

Maki agreed. "The whole occupational focus has changed" over the last few decades. Today, he said, people believe that "to make it in the world you have to go to [four-year] college."

But a four-year degree is not the right option for the majority of people. Rounds pointed out that many kids are mismatched in their initial career choices. Better than 70 percent of South Dakota high school graduates go on to college the following year, he said, and by the second year only a small fraction remain at their original choice of institution, with some likely transferring, others dropping out. "They weren't in the right spot," Rounds said.

Still, the "four-year or bust" mentality is a tough one to overcome, because it often starts in the home with parents. Jim McKeon, president and CEO of the Rapid City (S.D.) Chamber of Commerce, said he attended a meeting with about 20 community and business leaders, and there was widespread agreement about the future need for skilled trades workers. Then McKeon asked who among them was encouraging their kids to pursue such a path, "and of the 20 people in the room, not a hand went up."

Society believes that "there's a certain benefit to a college education, and a certain stigma to a noncollege education," McKeon said. "There's a push to gear everything toward [traditional] college, and we're not encouraging the value of a vocational education."

Belanger, from ABC of Wisconsin, agreed. "In Germany, a construction apprenticeship is gold." In the United States, he said, if a guidance counselor placed 20 high school graduates into apprenticeship programs, "he'd get fired."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.