Ever think about the sugar that goes into your morning doughnut, the one that tastes so good with that first cup of java?

If you have, chances are you think of lush, humid plantations of cane harvested by machete—not some turnip-looking root pulled from the cold, autumnal soil in the wind-swept Great Plains. But more sugar consumed in the United States comes from sugar beets than any other source, and those grow best in cooler northern climates like the Ninth District, where beets are big business.

If you have, chances are you think of lush, humid plantations of cane harvested by machete—not some turnip-looking root pulled from the cold, autumnal soil in the wind-swept Great Plains. But more sugar consumed in the United States comes from sugar beets than any other source, and those grow best in cooler northern climates like the Ninth District, where beets are big business.

There's a reason for the sunny stereotype though. Tropical countries have many advantages in sugar production, owing largely to weather and labor costs. And they are pounding on the trade door for greater access to the sweet-toothed U.S. consumer—which could in turn have serious repercussions for the district sugar beet industry.

Last year, the U.S. government, along with the governments of five Central American countries and the Dominican Republic—all sugar producers—signed the Central American Free Trade Agreement, or CAFTA. In order for the agreement to go into effect, it must be ratified by the U.S. House and Senate, where votes are set for this spring.

But if district sugar beet producers have anything to say about it, the effort won't pass without some major changes to its provisions on sugar imports.

CAFTA won't throw the U.S. border wide open to foreign sugar—far from it. Sugar imports are tightly controlled by the U.S. Sugar Program, an agricultural subsidy system that dates back to the 1930s.

Current imports from the nations involved are set at about 343,500 tons annually, or roughly 3.5 percent of domestic sugar consumption. The agreement will increase imports by 120,000 tons, an amount equal to about 1.2 percent of national sugar consumption. The program would then gradually increase additional imports to 153,140 tons annually, or 1.7 percent of consumption, over 15 years.

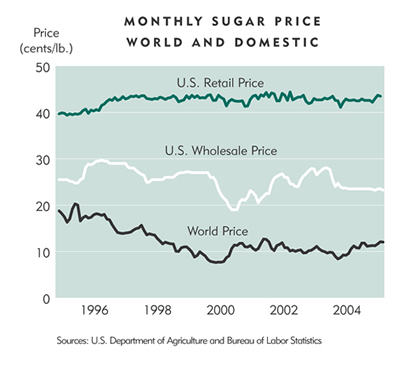

Compared even to production in the Ninth District, this extra bit is equivalent to sugar packets. However, producers maintain that this subtle increase could trigger a collapse in the sugar support mechanism that maintains a domestic price at around two to three times the world market price. Such a drop in price would have devastating effects on the U.S. sugar industry. And even if CAFTA doesn't rip the floor out from under U.S. sugar prices, producers here are worried the deal could set a precedent for upcoming bilateral trade agreements with other major sugar-producing nations, further increasing sugar imports and the likelihood of an eventual price collapse.

Is there reason to worry trade agreements might have negative implications for the business? Possibly.

The sugar industry in the Ninth District is sizable (see sidebar), and undoubtedly owes much of its success to government support for sugar. It is in part the threat to this support that has sugar producers worried.

Sugar daddy

The U.S. Sugar Program was set up in the 1930s to ensure an ample supply of sugar at a price that would allow sugar farmers to operate profitably. Unlike most other crop support programs, such as grain subsidies, it doesn't use a direct payment to growers.

| SUGAR QUOTAS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current quota |

First-year increase |

Total increase by 15th year |

|

| Dominican Republic | 203,869 |

11,000 |

14,080 |

| Guatemala | 55,601 |

35,200 |

54,802 |

| El Salvador | 30,117 |

26,400 |

39,644 |

| Nicaragua | 24,325 |

24,200 |

30,976 |

| Costa Rica | 17,376 |

14,300 |

17,688 |

| Honduras | 11,583 |

8,800 |

11,264 |

| Total | 342,871 |

119,900 |

168,454 |

Source: U.S. Office of the Trade Representative |

|||

Rather, the system functions as an indirect transfer from consumers. The Sugar Program keeps the domestic price of sugar at around twice the world price. It uses a combination of price supports and production controls to carry this out.

The primary price-support tool is the provision of loans to sugar processors. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Commodity Credit Corporation, lends cash at fixed rates per unit of production to ensure that processors like American Crystal pay farmers a minimum price for their crops. The CCC currently lends at 22.9 cents per pound for beet sugar and 18 cents per pound for cane sugar.

The loans have a term of nine months until payment is due. The processed sugar is used as collateral for the loans. If market prices are higher than CCC loan rates, then processors can pay back the loan and still make a buck. If market prices are below the CCC rate, processors simply hand over the finished sugar as payment on the loan.

The USDA has no facilities to store sugar, so it pays producers to do so. Under current policy, the government sells the sugar at the going market price. However, there is still a reserve price under which the USDA does not want sugar prices to fall, so sometimes it has difficulty selling its sugar.

The program ran into cost overruns around the year 2000, which sparked calls for reform. Its most recent overhaul, the 2002 farm bill, declared that the loan program should be run, to the extent possible, at no net cost to the government.

To eliminate losses, the bill resurrected another feature of the Sugar Program that has come and gone over the years—marketing allotments. The allotment program starts with an estimate of the annual consumption of sugar—about 10 million tons in 2003—and then subtracts an allowance for imports. The current import level is 1.532 million tons, which represents 1.256 million tons for minimum import requirements under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, with the remaining 276,000 tons representing Mexico's allowance under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The remaining U.S. sugar supply (about 8.5 million tons in 2003), set at a level that will hold prices at the desired level, is then allotted to domestic producers, roughly 54 percent of which went to beet farmers and the rest to cane. Production in excess of allotments cannot be sold and must be stored by producers at their own expense. Not all producers use their full allotment, but overall the sugar industry produced 99.3 percent of allotment in 2003. District sugar beet farmers did a little better than average in making allotments.

The catch in the allotment program is that allotments are suspended if imports exceed the threshold of 1.532 million tons. In this case, all the excess sugar in storage, currently around 600,000 tons, could go on the market. That is a major concern producers have with CAFTA.

It's rare for sugar imports to exceed this threshold because of two-tier import tariffs, the other major leg of the Sugar Program. The current tariff-rate quota program assigns permissible import levels to various countries, who then sell their sugar here at the domestic price with a low tariff. Any imports above the TRQ are assigned a prohibitively high tariff. Without these high tariffs, it would be impossible to hold the domestic sugar price significantly above the world price.

Sugar bane

The Sugar Program has long been the bane of subsidy opponents, because it is perceived to be a level of intervention even beyond other crop supports, and because of its protectionist nature. Opponents claim the program constitutes a tax on U.S. sugar consumers.

A 2000 analysis by the Government Accountability Office found that the program does indeed benefit producers at the expense of consumers. The GAO study estimated the cost to consumers in 1998 at $1.9 billion, with a benefit to producers of $1 billion and a net loss to the U.S. economy of $900 million.

Of that $900 million loss, the GAO estimated that about $500 million was due to inefficiencies caused by higher sugar prices, for example, when farmers decide to grow beets instead of other crops. The remaining $400 million consisted of transfers to foreign producers, who receive the higher price for sugar they sell in the United States.

Sugar industry representatives claimed the study, and other such comparisons, are unfair, because the world sugar price, which was used as a benchmark, is distorted. "Economists, a lot of times, look at a perfect world without subsidies, and what you're talking about are heavily subsidized countries," said Philip Hayes, spokesperson for the American Sugar Alliance.

To be sure, every country that produces sugar intervenes in some way in the market, whether through tariffs, subsidies or indirect means such as Brazil's massive ethanol program. Even the economists who developed the model used in the study admit as much.

"The question asked at the GAO wasn't conditional on what would happen if we could all liberalize," said John Beghin, professor of economics and head of trade and agricultural policy at the Center for Agricultural and Rural Development at the University of Iowa, who helped prepare the GAO study. "Definitely we would have prices easily 40 percent higher if the industry liberalized. That's the ballpark."

Those involved with the study still assert the comparison is meaningful, because it was based on the estimated effect on world prices if the sugar program were eliminated.

A final criticism of the Sugar Program is that it harms the United States' credibility on trade issues, especially with poor countries. The program also counts against agricultural support allowances under WTO rules. Even though the program is in compliance with rules on tariffs, it falls in the "amber box" category of trade-distorting agricultural subsidy programs. These include subsidy programs that don't offer direct payments for limiting production. Amber box spending is targeted by the WTO for reduction, and the United States is only allowed $19.1 billion worth. That's not necessarily a problem for sugar farmers, but it could be for agriculture overall.

"[T]he amber box limit that we currently face, that we're likely to face under a new [WTO] agreement, a disproportionate share of that is being taken up by sugar and dairy," said Pat Westhoff, economist at the Food and Agricultural Policy Institute at the University of Missouri, who also worked on the GAO study. "Even though we're not really transferring a lot of cash to farmers of sugar or producers of milk, a fair amount of our [amber box] is taken up that way."

Trade pacts: Do we hafta?

At first glance, it might appear that CAFTA would be no big deal to U.S. sugar producers. The Sugar Program can maintain the current price, and the added imports in the first year are roughly equivalent to a day's production in the United States. But the sugar industry is worried.

"The U.S. government's own estimates say that there will be more sugar workers put out of work because of CAFTA than any workers in any other industry. So CAFTA by itself is going to cost us thousands of jobs," Hayes said.

CAFTA amounts to an increase in the first-tier import quotas from the countries involved, which would fill an import gap that is currently unused. A primary concern is the suspension of allotments when sugar imports exceed the 1.532-million-ton threshold.

According to James Horvath, president of American Crystal, such an incident "could destroy the U.S. sugar market." Horvath and others fear that if CAFTA pushes sugar imports over the edge, the 600,000 tons of sugar currently blocked from sale would be placed on the market, and the price would plummet.

Could such an event happen? It actually did in 2000. At that time, there was no allotment program, and excess production pushed U.S. sugar prices down by 14 percent within a single month. The USDA ended up paying out about $300 million from 2000 to 2002 because of the drop, almost half of which went to Ninth District farmers. This also prompted the return to allotments in 2002.

"The biggest problem was that the domestic producers, for the third year in a row, increased production faster than the increase in sugar demand. It took three years before the seams burst and price plummeted," said Dan Colacicco, director of the Dairy and Sweeteners Analysis Group for the Farm Service Agency of the USDA, which administers sugar market allotments. "We took forfeitures over a million tons in the year 2000. Well, that's what happens, that's what can happen, if allotments go off."

The danger from CAFTA might not be that grave, however. One reason is that sugar imports currently fall short of the critical threshold by about three times the first year's increased import quota under CAFTA. Most countries don't actually send their full quota, and currently Mexico isn't exporting any sugar stateside because demand is stronger in-country due to a tax it has placed on high-fructose corn sweeteners used for food products like soda. So in the first year of CAFTA, there would likely still be a large gap between added imports and the 1.532-million-ton threshold.

"Just what effect imports from CAFTA countries have depends critically on what the policies are," said Westhoff.

Still, sugar producers are uneasy. Horvath, who went to Mexico recently for sugar policy negotiations, thinks a settlement might come soon that would open Mexico to corn sweetener imports and start its sugar exports flowing north again. On the not-too-distant horizon, in 2008 the U.S. border will open completely to Mexican sugar, under the provisions of NAFTA, with uncertain effects for domestic producers.

Officials at the USDA said they aren't worried about allotments going off, because there are ways of holding imports below the threshold. CAFTA itself includes an inventory management provision, which would allow the U.S. government to pay foreign governments the difference between the domestic and world price to keep their sugar out of the United States.

Still, there is a more important reason the sugar industry opposes CAFTA, which is strategic. "The long-term problem is that this sets a precedent with more than 20 other developing countries lined up behind the CAFTA countries, all demanding similar sugar deals," said Hayes, from the American Sugar Alliance.

Horvath agreed. "The Andean countries [Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela] export about 1.5 million tons of sugar a year, and they would like nothing more than to get a bigger chunk out of the U.S. market for a piece of that. Same situation with South Africa; they export about a million and a quarter tons a year. Same situation with Brazil; and Brazil exports about 18 million tons a year. Over half their total production gets exported, so they'd like nothing more than to get a bigger chunk of the U.S. market. And all these negotiations are going on with these countries, as well as with Thailand and Panama, all of which are huge sugar exporters. So you start setting a template here where the CAFTA agreement becomes the guidepost as to what the administration is going to do with the rest of these negotiations on free trade, and you end up with the U.S. sugar industry gone."

What is to be (un)done?

It's hard to say what Congress will do about CAFTA. The sugar industry would like very much for everything relating to sugar to be removed from the agreement. This precedent was set in last year's bilateral agreement with Australia, where sugar provisions were removed, to the chagrin of Australian sugar farmers.

However, Central American governments would be unlikely to go for such a deal, since sugar is a major product in their economies, and they feel they've already made enough concessions.

Not surprisingly, Horvath and others in the industry say they would support CAFTA if only they got assurance that imports would be held down so marketing allotments would not be suspended. But Horvath claims, "We've had no words of comfort, if you will, from the administration at all."

Sugar producers may take some comfort in the fact that policymakers don't see a likely threat to the Sugar Program before the next farm bill. The USDA has an incentive to defend the threshold, since suspending allotments could create a major financial liability for the USDA, as in 2000. And given how important sugar is to some areas where it is produced, like the Ninth District, it's hard to see the program just getting scrapped.

But what about the long run? What about future trade deals? Horvath insists sugar producers aren't protectionists. "We are in favor of worldwide trade in sugar, and we're perfectly willing to compete in that environment," Horvath said. "We would like to see sugar trade handled at the WTO level and not in these bilateral agreements. All that distortion can't be taken out in the bilaterals, but it can be addressed at the WTO level."

Horvath contends the U.S. sugar business wouldn't be at a disadvantage in a free market, because U.S. production costs are in the lowest third worldwide. U.S. sugar is higher quality as well and competes in a different category from most of what is produced internationally. However, most in the sugar industry are quite happy leaving the Sugar Program as it is, but it would most likely need heavy modifications if the sugar trade were handled multilaterally.

Westhoff, of the University of Missouri, suggested that converting the program to something like other crop supports would reduce the aggregate measure of support allowances under WTO rules. But that comes with its own problems.

"One of the concerns that has been raised is that given the structure of the sugar industry, especially the cane industry, you'd have potentially very large payments going to very few people in some parts of the country. And whether that's at all politically sustainable is an open question in some people's minds," Westhoff said.

"There aren't any simple stories when it comes to sugar."

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.