The sewers in Geddes, S.D., are literally falling apart. For more than 85 years, sewer mains made of clay tile had done their job quietly and efficiently, collecting wastewater from homes and businesses and piping it away for treatment and eventual discharge into a creek. But recently the clay tile started cracking and crumbling, impeding sewage flow and letting in groundwater that threatens to overwhelm the town's wastewater treatment plant when it rains. The small town near Mitchell, 60 percent of whose residents are retired, must come up with almost $1 million to fix the problem.

Water infrastructure to bring clean water in and carry wastewater away is the civic equivalent of the human circulatory system; we don't pay attention to it until the hidden machinery starts breaking down. When a leaking water main carves out a sinkhole under Main Street or a wastewater lagoon overflows or water from the tap no longer meets health standards, we become all too aware of vital plumbing that should have been upgraded or replaced years ago.

Across the district that plumbing is failing, threatening the economic health of communities. National studies by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reveal a need for billions of dollars in water infrastructure improvements in the district, a sizable amount of it in systems serving nonmetro areas.

Often those needs are put off, particularly in small towns and rural areas. Paralyzed by the high cost of staving off decay or complying with tightening federal regulations, many small communities have stood pat for years, inviting censure from environmental agencies and in some cases restrictions on residential growth. Strasburg, N.D., will violate the EPA's new standard for arsenic in drinking water when it becomes effective Jan. 1. New York Mills, Minn., famous for its annual Great American Think-Off philosophical debate, is trying to figure out how to raise nearly $4 million to upgrade its aging wastewater treatment plant. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) has imposed a conditional moratorium on new sewer hookups until the project is complete.

Cutbacks in government financial assistance over the past 25 years have contributed to the woes of rural water systems. No longer can small towns depend on generous state and federal grants to pay for major water overhauls, said Nancy Straw, president of West Central Initiative (WCI), a Fergus Falls, Minn., foundation that has studied water infrastructure needs in Minnesota. "Most of the time they thought that all they would have to do when the time came is just call the right agency, and the money would appear to solve all the problems they might have with water," she said. "That, of course, isn't the case anymore."

But in many cases the fault lies with local governments that have failed to do what's necessary to upgrade aged or obsolete facilities—namely, charge residents the full cost of water services. Accustomed to levying only nominal fees to maintain water and sewer systems that were built largely at taxpayer expense, communities raise rates only when absolutely necessary—when the EPA knocks on the door, for instance, or to qualify for a low-interest loan. So scores of small towns in the district play for time—nursing along decrepit equipment, negotiating extensions with EPA and state pollution watchdogs—while holding out for government grants.

Still, most rural communities have the power to bring their crumbling or outmoded drinking water and wastewater systems into the 21st century. By exercising market discipline—charging water users what it actually costs to provide an essential commodity—small towns can take advantage of low-interest government loans or generate enough revenue to finance water infrastructure improvements themselves.

Small systems, big problems

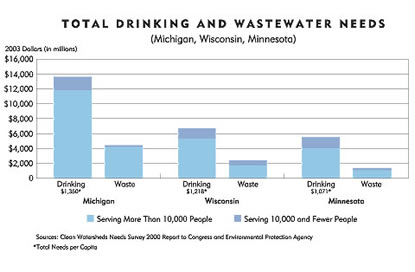

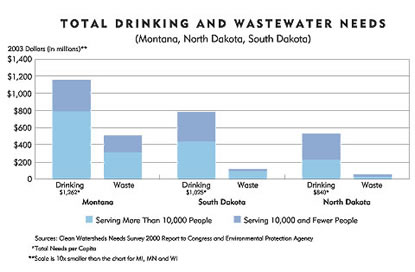

In surveys conducted in the past five years, the EPA found a near-term need for $36.9 billion in improvements to drinking water and wastewater systems in district states. In the semi-arid, lightly populated Plains states, a large proportion of that need is in small cities and towns-communities less able than metro areas to pay for upgrades (see charts).

Increasingly stringent EPA regulations have upped the ante for drinking water treatment in small towns, especially in the Great Plains, large swaths of which suffer periodic droughts and depend on well water of dubious quality. Complying with the new arsenic rule will be expensive for cities such as Strasburg and Cosmos, Minn., that draw their water from wells drilled into arsenic-laced bedrock. Communities elsewhere in the Dakotas, Montana and western Minnesota are struggling to meet tougher standards for nitrate and radioactive isotopes.

"The problem here is pretty simple," said Dennis Davis, executive director of the South Dakota Association of Rural Water Systems. "To meet the EPA regulations, it takes either a very sophisticated water treatment plant, which is costly to operate, maintain and run ... or it means you have to go to a site where the water is of very good quality, with limited treatment." Pipelines may be needed to transport water from a distant well or stream, either as a substitute for contaminated water or as a supplement to supplies hit hard by drought. In some cases, those pipelines can be extremely long and expensive (see "Pipe dreams").

Small towns are also struggling to comply with wastewater regulations. In the last 10 years, state pollution control agencies have taken an increasingly dim view of surface water and groundwater pollution caused by disintegrating or inadequate sanitary facilities. Proper wastewater disposal is of particular concern in the eastern part of the district, rich with lakes, streams and wetlands. A 2003 WCI survey of municipal water infrastructure needs in the foundation's nine-county, lake-studded region of Minnesota found that almost half of the immediate need for facility replacement and upgrades—about $235 million—was in wastewater and storm sewer systems.

Procrastination is a typical response to looming water crises, said Ken Blomberg, executive director of the Wisconsin Rural Water Association (WRWA), a nonprofit organization that provides training and technical assistance to small communities. "The small towns are just holding on," he said. "As long as the water keeps coming out of the tap, and the operators can keep the systems running, they're putting off big projects."

Often nothing is done until a government edict arrives in the mail. Strasburg, Columbus and at least a dozen other cities in North Dakota face the prospect of fines and criminal penalties under the new arsenic rule, which was announced in 2002. To extend the Jan. 1 deadline, cities must file a compliance plan with the state Department of Health. In Minnesota, the MPCA had restricted additional sewer hookups in 50 communities as of last February. The 4-year-old moratorium on sewer connections in New York Mills will remain in effect until the city finds the money to complete an expansion of its wastewater treatment facility. Additional hookups—including service for new businesses—must be negotiated with the MPCA.

In other instances communities have no choice but to try to rebuild water systems that are coming apart at the seams. In Geddes, the ancient clay-tile sewers—similar to those running under the streets of rural communities across the district—have been failing for two or three years. "We need to have extensive work done. There are a few places that are going to get critical not far down the road," said Ron Dufek, a city councilman who owns an auto repair shop in the town of 250 people. An engineering firm estimated that extensive renovations to fix leaking pipes and replace crumbling manhole covers will cost $940,000.

Going down the drain

The economics of financing new water towers, treatment plants, wastewater lagoons and other water infrastructure works against rural communities, particularly very small towns or unincorporated settlements. Small-town water departments and rural water districts lack the economies of scale that allow metro water systems to spread the costs of capital improvements among hundreds of thousands of business and residential consumers.

A typical method of financing water projects is to float municipal bonds, which residents pay off on their utility or property tax bills. But according to the WCI survey and a separate 2004 study of wastewater needs and capital costs in Minnesota by the MPCA, small towns often struggle to self-finance because project costs must be borne by relatively few ratepayers. The MPCA study shows that communities of fewer than 600 people have the hardest time paying for water improvements; below that population threshold, per capita bond payments for most wastewater projects rise above 1.5 percent of median household income—a federal benchmark for affordability.

Because aging or obsolete facilities were built decades ago-either for free by the Civilian Conservation Corps, or virtually for free, thanks to generous federal grants available for water projects in the 1970s—city councils and town boards have been largely oblivious to the true costs of replacing or upgrading water infrastructure. Reserve funds for major renovations don't exist in most communities. Subsidizing typically low water and sewer rates (in Minnesota, most small towns charge $7 to $20 per month for basic water service) with other revenues is common practice. "Many communities who had their systems put in free of charge haven't ever thought about there being a cost associated with that over the long term," said Straw of WCI.

Tiny communities with stagnant or declining property values can also run up against state-mandated bonding ceilings. South Dakota, for example, caps municipal bond issues at 10 percent of assessed value. That leaves Geddes, with a total assessed valuation of about $4 million, powerless to finance its sewer project solely with bonds. "The only way the community is going to be able to fix this problem is if somebody comes up with grant money for them," said Jay Larson, a rural development specialist with Midwest Assistance, a New Prague, Minn.-based organization that helps rural communities develop and rehabilitate water and wastewater systems.

But free money doesn't gush forth from Washington, D.C., as it did in the 1970s, when hundreds of rural water projects across the district were bankrolled with federal grants. Since the 1980s, the EPA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Rural Development arm and other federal funding agencies have shifted their focus to low-interest loan programs that require communities to pay back the U.S. taxpayer's upfront investment in water infrastructure.

Rural Development, the chief source of grants for rural water projects, has historically funneled about 40 percent of its funding for community water projects into grant programs. But in the 2005 fiscal year, grants accounted for only 30 percent of the agency's $1.5 billion budget for water and wastewater financial assistance programs; the balance was allocated to low-interest loans. The underlying message—there's no free lunch—is deliberate, said Jim Maras, director of water programs for Rural Development in Washington. "We're trying to teach [rural communities] that there is a cost to having clean drinking water and systems that release clean wastewater into the environment."

Other programs at the federal and state level have beaten a retreat from grants for water projects. The Bush administration has proposed cuts in community development block grants available through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Minnesota's Wastewater Infrastructure Fund, which provides supplemental grants and loans for sewer projects, funded only $557,000 in projects last year—a drastic reduction from three years ago, when $10.4 million in grants and loans was awarded.

Plumbers' helpers

Yet the situation isn't hopeless for small towns forced by regulatory fiat or the passage of time to tackle major water infrastructure projects. Competition for scarce grant dollars is fierce, but every year dozens of small, economically distressed communities across the district receive grants, usually combined with a loan. Under Rural Development rules, communities whose residents earn less than 80 percent of rural median household income in the state are eligible for water and waste disposal grants covering 75 percent of project costs. Towns earning more than 80 percent of the nonmetro median household income in their state qualify for a 45 percent grant. Earlier this year Crystal Falls Township, a settlement of about 500 homes in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, received a $2.2 million grant from the agency to help pay for replacing leaking water mains and constructing a new water tower and well.

HUD grants are also still available for low-income communities; this year Minnesota's Small Cities Development Program awarded grants totaling $2.9 million to four small towns in the state for wastewater collection and treatment projects.

Cash-strapped communities that would rather not wait for a grant—it can take years to rise to the top of funding priority lists—can take advantage of low- or zero-interest government loans. Despite budget cuts, district communities receive hundreds of millions of dollars in loans for water projects annually, through both Rural Development and state revolving loan programs that leverage EPA funding through bond issues.

Adjusted for inflation, Rural Development funding for drinking water and wastewater loans in district states has stayed about the same since 2001. In fiscal year 2005 eligible communities could apply for $94 million in low-interest loans through the agency. Wisconsin's Clean Water Fund Program, which supports wastewater treatment and storm water projects, lent communities $171 million at below-market interest rates in fiscal 2005. Every municipality and sanitary district that applied received funding, said Bob Ramharter, section chief for environmental loans with the state Department of Natural Resources.

Communities don't have to be destitute to qualify for these loans; they need only demonstrate the ability to pay the money back over 20 to 40 years, from tax receipts or fees charged to water users.

There's the rub for small towns; to repay a $1 million loan a community of fewer than 1,000 people would have to dramatically increase water or sewer rates—an unappealing prospect for any elected official. As a result, many towns with failing or obsolete water systems never ask for a Rural Development or state loan. Or they drop out during the application process, opting to put off upgrades to another budget cycle. "Far more communities that have needs say they want the money than communities that actually follow through and build the project and get the loan," said John Schnickel, coordinator of Minnesota's $40 million drinking water revolving fund.

Communities that do take out government loans, and raise water rates to repay them, risk the wrath of voters, many of whom are either poor or on fixed incomes. But they're getting a bargain—loans at interest rates that a CFO in private industry would die for. In June the city of Cosmos accepted a $991,000 low-interest loan from the Minnesota Public Facilities Authority, which administers the state's drinking water revolving fund, to pay for a new water treatment plant to filter out arsenic. The interest rate on the 20-year loan is 1.7 percent, less than half the going rate for municipal bonds. Over the life of the loan, the town will save about $263,000 in interest.

Mayor Gary Martin said that repaying the loan will be difficult for the farming town of 580 people. "We've only got 260 water bills to send out," Martin said, "so it's a hardship for everybody, what with fuel prices and taxes and health insurance going up. There's no end to it." But perhaps Martin protests too much; to begin paying off the loan, the city raised water rates by only about 30 percent, to a flat rate of $8 per month, plus $4 per thousand gallons used.

Imagine: Paying more for water

Low-interest loans, grants and other forms of public subsidy for water infrastructure upgrades in rural areas would be largely unnecessary if water was priced appropriately. Most households in the district pay less for water and sewer than any other utility service because municipalities treat water mostly as a free good and price it as such. Residents pay only what it costs to pump, treat and distribute water, and sometimes not even that much. "We're not paying enough for water," said Blomberg of the WRWA. "People just expect it to be free, like it is. That's the way it's always been."

In WCI's 2003 infrastructure survey, some cities and townships in west-central Minnesota charged as little as $10 a month for water and sewer service. Until recently residents of Geddes in South Dakota paid just $3.50 per month for sewer service—a rate that Ron Dufek admits was too low. Positioning itself for financial aid, the city council voted in June to raise the fee to $17 a month.

Grants may be the only way to solve the problems of Geddes and other tiny communities with withered tax bases. But the best evidence suggests that even modestly larger or more affluent towns could raise the money for long-overdue improvements themselves if they charged residents as much for the privilege of flushing the toilet or taking a shower as they readily pay to be able to switch on lights, watch TV or go out to dinner. The WCI study found that Minnesota communities with at least 600 people can generally self-finance water projects if each household pays about $100 a month for water, sewer and storm water service.

Paying more for water and sewer service may go with the territory in a small town where infrastructure costs must be borne by a few hundred households. Undoubtedly, given the number of TV satellite dishes sprouting from back yards in rural areas, most rural residents could afford to pay more for water. The prospect of rate hikes for infrastructure improvements also provides an incentive for communities to try to pare costs by sharing facilities and staff with other towns or deploying unconventional technologies (see "The path not taken").

Blomberg believes that small municipalities and rural sanitary districts in Wisconsin will have no choice but to double or triple water and sewer rates in coming years in order to meet immediate infrastructure needs and build up cash reserves for upgrades five, 10 or 20 years down the road.

Savvy marketing may help soften the blow, he adds. Earlier this year the WRWA launched a public relations campaign on behalf of rural water systems, bottling and distributing tap water to members to be used in fund-raising promotions. Each 20-ounce plastic bottle, priced at 29 cents, carries the Rural Water logo, a la Evian and Perrier. Blomberg asserts that the water is as pure and healthful as the stuff that sells for $1.50 per bottle in stores. The message: Consumers don't realize that municipal water is a heckuva deal.

When people finally understand the value of a clean glass of water," Blomberg said, "they'll do two things if the utility needs to raise the water rates: They probably won't waste as much water as they do, and they'll appreciate it more."