When Canadian bread maker George Weston Limited decided to get into the cookie and cracker market in 1946, it set its sights south of the border. During the next two decades, the Toronto-based company acquired several existing U.S. firms, officially naming its expanded bakery products division Interbake Foods Inc., in 1967.

Today Interbake is the third-largest manufacturer of store-brand cookies, crackers and ice cream novelty products in North America. The international organization has nine locations, including a 260,000-square-foot manufacturing, warehouse and office facility in North Sioux City, S.D. From company headquarters in Richmond, Va., Interbake president and CEO Raymond Baxter said George Weston's decision to set up shop in the United States was a no-brainer. He cited the sheer difference in market size between the two countries, noting that the current population ratio of 10-to-1 was roughly the same in 1946.

"If you're sitting in Toronto looking south, you realize that the U.S. is the place you want to be," Baxter said.

AKG, a manufacturer of cooling and heat exchangers based in Germany, is opening its second U.S. plant, this time in Mitchell, S.D. The new division, AKG Midwest Inc., plans to create 100 to 160 jobs with a capital investment in excess of $7 million over the next three years.

When a foreign firm buys a company in another country (which is how Interbake entered the U.S. market 36 years ago) or starts up operations there from scratch (like AKG first did in North Carolina in 1981 and will again in Mitchell) or invests in capital expansion for existing U.S. operations (as Interbake expects to do in North Sioux City), it's called foreign direct investment, or FDI.

The debate swirling around globalization often focuses only on the expansion of U.S. firms abroad and the jobs that are either lost or not created in the process. What often goes unnoticed is that this phenomenon goes both ways; each year, the United States is also the recipient of an enormous amount of capital from foreign companies looking to establish or expand their U.S. presence.

The United States is the leading recipient of cumulative FDI, hosting more than $1.5 trillion, or 19 percent of all FDI stocks worldwide as of 2003, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. These FDI stocks help create jobs and increase domestic production. The share of FDI that lands in district states is relatively small, but firms like Interbake and AKG show they can have lasting economic effects. While globalization critics and advocates arm-wrestle over the effect of capital flows in and out of the country, hard conclusions about the net effect of FDI are difficult, if not downright impossible, to determine given available data.

That's due, in part, to the fact that FDI runs counter, or at least sideways, to the traditional notion of investment, which views investment as expenditures for capital and other assets for the purpose of increasing production, giving investment a tangible link to gross domestic product. In contrast, FDI can be a simple exchange of assets, like when Interbake bought control of the Johnson Biscuit Company in 1969; there was no net increase in production as a result of the purchase itself, but merely a change in ownership. Current research counts virtually all new spending by foreign-owned firms in the recipient country as FDI, when a more careful vetting of the data would count only those activities that add to GDP. As a result, FDI figures are often misinterpreted as inducing more gains in capital spending, production and employment for the recipient country than FDI is really responsible for.

Expecting company

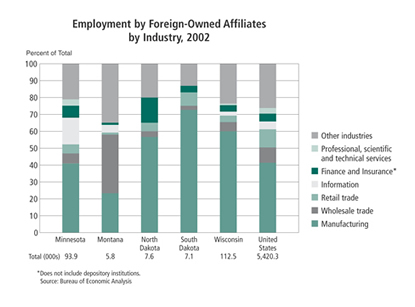

Foreign companies employ around 5 percent of the entire U.S. workforce. (See chart.) The Ninth District has a somewhat smaller presence, with only 4 percent of workers employed by companies headquartered abroad in 2002. Wisconsin is the only district state that approaches the national average.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Employment at foreign firms in the district appears to have grown faster than the overall rate of job growth in the last few years. Between 1997 and 2002, the number of district workers employed by foreign firms jumped nearly 51 percent, to a total of 226,900 jobs. That's a pretty substantial jump compared to the national increase of 27 percent.

With workforces roughly six to eight times as large as those in the other three district states, it's no surprise that Wisconsin and Minnesota reaped the lion's share of job growth among foreign-owned firms. Wisconsin played host to roughly one out of every two such additional jobs over the five-year period, while Minnesota grabbed just over 40 percent. (However, not all of these jobs are necessarily "new"—more on that later.)

While still at or near the bottom of the national rankings, the number of workers employed by foreign firms more than doubled over the period in North Dakota and Montana—to 7,600 and 5,800 jobs, respectively. South Dakota was the only state to register an overall decline, slipping 26 percent to 7,100 jobs in 2002. Buoyed by Wisconsin's and Minnesota's growth, the district as a whole managed to boost its percentage of overall employment held by foreign-owned firms, even as the national benchmark stagnated and declined slightly.

Getting the cold shoulder

Still, judging from aggregate numbers, the district is a relatively unattractive FDI destination for various reasons.

The biggest factor may be that district states—especially the Dakotas and Montana—are sparsely populated and have relatively small state economies. Robert Kudrle, an economist and professor of public affairs and law at the University of Minnesota, said that several studies (including his own) have found a pretty strong correlation between the size of the state (in terms of population or economic output) and the amount of FDI it receives. In fact, the state rankings of South Dakota, Montana and North Dakota for gross state product are similar to their FDI rankings. (See state rankings in chart.) Minnesota's GSP of $200 billion was good enough for 17th place, while its FDI ranked 31st, indicating that size isn't the only determinant of a state's ability to attract foreign capital.

Another factor dampening district FDI could be the frigid winter weather. Even the general geniality and industriousness of the people who live and work in the district probably aren't enough to outweigh the brutal winter cold, especially when more temperate U.S. locations abound, Kudrle said.

"It's hard to prove with the data that's available, but I would say it's pretty likely that cold weather plays a part in curbing foreign" investment in district states, he said.

Given the severity of the winters, it's not surprising to find that a notable share of the region's FDI comes from firms based north of the border. Canadian companies employed almost one out of every six workers at foreign-owned companies in the district in 2002, but only one in 10 nationwide. In the district, Minnesota and South Dakota appear to be particular favorites of their Canadian neighbors. (See chart.)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

When Manitoba-based New Flyer decided to expand its business in the United States, subzero Minnesota winters weren't a deterrent. The company built a state-of-the-art bus manufacturing facility in St. Cloud, Minn., in 1999, hiring around 300 people. Since that time, employment at the plant has expanded to meet growing demand from U.S. transit authorities. Paul Smith, executive vice president for sales and marketing, said the facility now employs around 525 workers.

Smith said the company chose to build the plant in the United States in part because of the Federal Transit Administration's Buy America rule. The rule states, among other things, that the FTA will only reimburse local transit authorities for buses constructed with at least 60 percent domestic inputs. In addition, final assemblage must take place in the United States. New Flyer responded to this regulation by constructing the St. Cloud facility to handle everything from welding to final assembly.

"By building the buses cradle to grave in St. Cloud, we knew we could avoid any issues related to the rule," he said. Smith added that the company settled on St. Cloud for several reasons, including the quality of the local workforce and the city's proximity to the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area.

European companies make up the largest share of total FDI, in both the district and the nation as a whole. Together, European businesses employ 70 percent of the district's foreign-owned workforce. According to Harvard Business School scholar Geoffrey G. Jones, European companies have historically been bullish on investing in operations abroad—the British and Dutch alone accounted for between two-thirds and three-fourths of total worldwide FDI between 1914 and 1980. While Japan has taken a big bite out of European supremacy since the 1980s, European countries combined still have a mammoth presence around the world and in the district.

Headquartered in Fargo, N.D., Global Electric Motorcars (known as GEM) is the leading manufacturer of neighborhood electric vehicles. The company was acquired in 2000 by Stuttgart, Germany-based DaimlerChrysler. GEM marketing coordinator Christopher Mohs said DaimlerChrysler purchased the company in part to help meet its obligation under U.S. law to expand the number of alternative-fueled vehicles in its fleet. The Fargo facility is essentially a "small auto plant" employing a variety of workers, Mohs said. "The Fargo plant has all of the same departments as a regular auto assembly and sales facility. The core GEM engineers are based in Fargo, along with the full service and sales department and all upper-level management," he said.

Manufacturing facilities like those operated by New Flyer and GEM are the most common type of foreign operation. While the manufacturing sector supports only around 14 percent of all workers in the U.S. economy, it comprises more than one-third of jobs at foreign companies in the nation and around one of every two in the district. (See chart.)

Kudrle's 2000 report on state FDI notes that one reason manufacturing is such a large part of all inward foreign investment is that foreign manufacturers who have been exporting goods to the United States for some time probably realize that they can achieve greater sales and cut down on transportation costs by establishing a U.S. presence. The New Flyer example also hints at the role regulations play in encouraging companies to build manufacturing facilities within U.S. borders.

Beyond manufacturing, each state receives investment in sectors that make up a substantial portion of its existing industrial mix. In Montana, that sector is mining. Rio Tinto, based in the United Kingdom, is one of the world's largest multinational mining conglomerates with operations and subsidiaries on six continents. It owns the Yellowstone talc mine in Three Forks and a 50 percent interest in the coal mine in Decker. The two locations combined employ around 270 workers.

Fuzzy FDI math

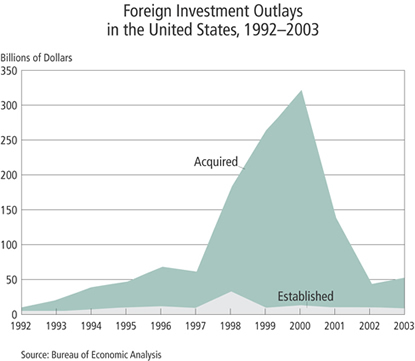

Between 1999 and 2004, corporations worldwide invested between $500 billion and $1.3 trillion annually in their operations overseas, a volatility that reflects the health of the world economy. The high-water mark came in 2000, before the U.S. recession and its ripple effects around the globe. By 2003, annual worldwide flows had fallen nearly 70 percent as falling consumer demand and sluggish economies in much of the developed world put a damper on corporate investment abroad.

The recession also took a toll on FDI received by the United States relative to other FDI hot spots around the globe. Between 1985 and 2003, approximately 70 percent of total FDI flows landed in one of three places—the United States, the European Union and China. Although the United States is number one in cumulative FDI stocks, in 2003 it hosted only 5 percent of total flows—down from an average of 24 percent between 1985 and 1995. During the same stretch, the European Union's share of incoming FDI increased from 36 to 53 percent, while China's take increased from 7 to 10 percent and exceeded FDI inflows to the United States for the first time in 2003. Historically, FDI inflows have exceeded outflows for the United States, including as recently as 2001. But in 2003, FDI outflows exceeded inflows for the United States by $122 billion.

What all of this means for state economies in the district is unclear. While FDI flows are used to support arguments both for and against free trade and globalization, the veracity of any specific claim is tough to confirm. On the surface, expanding employment growth among foreign-owned firms demonstrates a greater presence in the region. But the net economic effect is uncertain, because comparing jobs supposedly gained or lost through FDI flows is tedious and offers, at best, an incomplete picture. For example, calculating the exact number of jobs lost and other economic activity not generated when a U.S. firm decides its next new plant will be in, say, Bangladesh rather than Bismarck is tricky to say the least.

Even calculating the number of new jobs due to inward FDI in district states is problematic. Much of the inward FDI comes in the form of mergers or acquisitions of existing U.S. companies. As a result, many jobs attributed to FDI inflows are not new jobs, but the same jobs reporting to new (and foreign) ownership. And this caveat is an important one: in previous years the proportion of acquisition expenditures for inward U.S. FDI has been greater than 80 percent.

(See chart.)

This distinction had led some to discount the positive impact that FDI really has on U.S. and state employment. But Kudrle said assuming only new, or "greenfield," investments contribute to state employment is an oversimplification.

"Foreign firms that are in the position to make acquisitions almost certainly enjoy some sort of competitive advantage in their industry. These companies are likely to exploit that advantage and gain market share, which often leads to expanded production and employment," he said. He also noted that greenfield investments don't usually snap up local idle workers to staff their facilities. Rather, the companies usually draw workers from the larger regional and national labor markets.

Production and employment certainly picked up after Johnson Biscuit Company was acquired by Interbake in 1969. Operations quickly outgrew the aging facility in Sioux City, Iowa, and the company built the current larger facility across the border in North Sioux City, S.D. Both production and employment have grown in lock step with Interbake's surging share of the chocolate-covered-cookie market. Baxter said the facility doubled in size in 1994 and employment expanded to 525. He also said the facility is poised in the next six months for its second major expansion.

"By the middle of next year, the plant will employ 750 people," he said.

Acquisition meant growth for GEM as well. Mohs said parent DaimlerChrysler used its size and name recognition to aggressively promote the electric vehicle not only in the neighborhood transportation market but also for other uses at golf courses, airports, military bases and national parks. Since acquisition in 2002, Mohs said GEM has undergone "steady and controlled growth," and production is way up. At the time of acquisition there were around 2,000 GEM vehicles on the road; now there are approximately 30,000. Beyond adding jobs, he said the region also benefits from increased production because approximately 90 percent of GEM's inputs come from the surrounding Red River Valley.

When asked why DaimlerChrysler hasn't whisked the GEM headquarters off to a warmer locale, Mohs noted that the manufacturing infrastructure and workforce were already in place. He was also quick to add the intangibles. "I think DaimlerChrysler recognizes that Fargo's diligent workforce and quality of life aspects are a benefit."