Most communities nationwide are rife with complaints about high gas prices. But in some parts of the Ninth District, the prospect of a $60 barrel of oil has people dancing in the streets.

"It's good for the community. I think everybody pretty much up and down Main Street is benefiting at this particular point," said Ward Koeser, mayor of Williston, N.D.

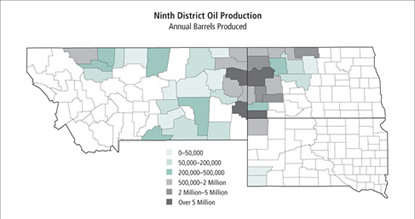

Counties in western North Dakota and eastern Montana are home to almost all the Ninth District's oil production, and ever since the price of oil began jumping last year, those areas have seen major increases in

oil-drilling activity and related businesses.

But it's not the first time this region has seen so much growth, and the recent activity has some residents recalling unhappy memories of the busts that followed previous booms.

Sources: North Dakota Industrial Commission's Oil and Gas Division, Montana Department of Environmental Quality, South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources

They might not have much to worry about. As far as anyone can tell, the growth this time around has been more measured, and market conditions could support more drilling for a long time to come. But when it comes to oil, predicting the future has always been a slippery subject.

A bubblin' crude

Compared to giants like Texas and Alaska, Ninth District states are not major players in the oil game. Still, it is a big business in relatively small states.

Almost all the oil is located in the Williston Basin, which spreads out over parts of Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Saskatchewan.

The biggest oil producer in the district is North Dakota, with proven reserves of roughly 353 million barrels, ranking it eighth among the states. Daily production early this year averaged about 92,000 barrels of crude a day. Put in a national context, North Dakota accounts for only slightly more than 2 percent of national reserves and about 1 percent of production.

North Dakota's total proven reserves are equal to 4.7 percent of U.S. oil consumption in 2004, meaning its reserves would supply the country for about 17 days at current consumption levels.

Montana ranks ninth among all states with 315 million barrels in reserves and recent production at 86,000 barrels a day. South Dakota also has considerably smaller oil reserves and produces about 3,000 barrels daily.

In a region where the only other significant businesses are agriculture and tourism, petroleum is a major industry. An estimated 3,900 people are employed directly in the industry in North Dakota, with 2,400 in Montana, not to mention those employed in energy services. With current North Dakota light sweet crude prices hovering around $52 a barrel, the present level of production in the Ninth District will yield roughly $3.4 billion this year. Last year's estimated $1.1 billion in oil revenues for North Dakota were equal to 4.7 percent of its gross state product.

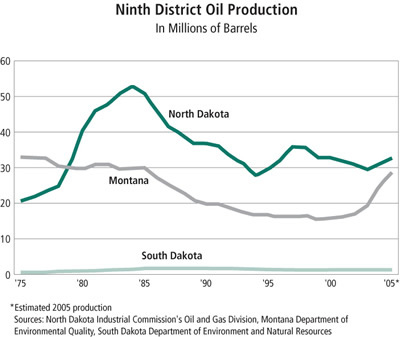

What is surprising, though, is that just a few years ago production was much lower in those states. Current crude production is up 14 percent in North Dakota from as recently as 2003. In Montana, it's up a whopping 62 percent. The low point in district oil production since the last boom was 1994, when production was 45.7 million barrels. Production in 2004 was 24 percent higher than that low, and it is up even higher so far this year, looking to easily top 62 million barrels by year's end. But for most of the period leading up to the current boom, production hovered around 50 million barrels.

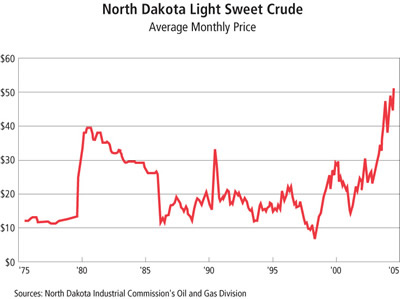

The driving factor is obviously those soaring crude prices that have consumers so angry. Sometime last year growing world demand began putting heavy upward pressure on oil prices, and spigots in the Williston Basin opened up. High prices make it economical for the region's producers to extract high-cost oil from the Williston Basin.

"We've got oil, but it's expensive oil; it takes about 27 bucks to extract a barrel," said Paul Polzin, director of the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana. "So when the world price of oil was about $20 a barrel, it's not worthwhile to extract it."

Polzin puts the turning point around last year when the world price of oil crossed $30 a barrel. That explains why the business was so slow for so long, with such low prices in the '90s. The average price in 1994, the slowest production year in the recent past, was $14.72 a barrel. In 1999, when the oil price dropped below $10 a barrel early in the year, the district rig count was down to 11. It currently sits at 44.

Growing pains

Like many customers at the pump, the industry and the region were caught off guard by the price spike. As a consequence there has been economic pressure on employers and developers to keep up the pace.

"The run up to the $40s and $50s in terms of oil price I think surprised just about everybody in the business," said Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota Industrial Commission's Oil and Gas Division. "There's a lot of people writing articles saying it shouldn't have surprised us, but it did. And I think that's because there just wasn't information publicly available to quantify the demand growth that's been taking place in India and China."

The oil prices were such a surprise to Polzin and his staff that in June they made an upward revision to their growth forecast for the Montana economy. "The number one thing that caused us to revise our estimate was oil," he said.

One of the harsher consequences of this pleasant surprise is the difficulty of finding enough oil workers to do all the drilling. Part of the problem comes from past cuts in the oil and related industries 15 to 20 years ago when thousands of employees were laid off. Many skilled workers had to move to other regions or switch occupations, and now there is practically no latent skill pool to tap into.

In North Dakota the demand for workers became so dire last fall that the industry worked with the state government to fill jobs. In October 2004, Job Service North Dakota posted 100 openings in oil field positions. Since then, all 100 of those jobs have been filled, along with 114 more, but now the Web site has an additional 250 job openings listed.

The openings range from "roughnecks" who work on drilling rigs to engineers and geologists, along with a wealth of jobs in energy services, such as drivers to haul trucks full of crude oil and saltwater.

Predictably, the labor shortage has been accompanied by an increase in pay. Helms estimated the rise in hourly wages and benefits at 30 percent to 40 percent over the last year along with production incentives. But in a state with low unemployment and a tiny population, even such bonuses may not be enough.

Another problem is finding quality labor. Roughnecking is dangerous work, and oil drillers must find safe employees to keep their accident rates and insurance costs down. Some companies have said that as many as three-quarters of their applicants fail their drug screen.

In addition to the short-term gap in manual labor, there is a troubling long-term lack of skilled workers. "There's a severe shortage of geologists, engineers, master's-, Ph.D.-level people. There are very few people in the programs or graduating from the programs," Helms said.

While it takes only a few weeks of training to be competent in oil-rig and truck-driving jobs, according to Helms, "If you're looking for an engineer or geologist, especially at the research level, you're four to six years out."

While enrollment in such programs is back up, it is still low, and most of those enrolled in programs at U.S. universities are foreign students planning to return to work in their home countries.

That fact opens the door to an interesting scenario. "We are seeing the development of non-U.S. service companies. We could see the day where we have a Russian or a Chinese Schlumberger or Halliburton

(two major U.S. oil firms) actually doing work in the United States," Helms said.

In addition to the labor demand, there has been an ensuing demand by that labor for housing, which some communities are having trouble meeting.

"We are dealing with the challenge of a shortage of housing. We have had a number of people who have moved here, and that's difficult,"said Williston Mayor Koeser.

Williston had a population of 12,500 in the 2000 census, and since the oil business took off, the number now sits around 14,000, Koeser estimates. The town has some builders who are responding, but no major developers to put up big projects.

"One of the issues that's different this go-around from the last one is that in the last oil boom, the economy of the country was pretty soft, and so you found developers and people moving to Williston as a business opportunity. Whereas, now with the economy pretty strong all over the country, they're not about to move from a Fargo to Williston, because the economy is so strong in Fargo, so that's a challenge for us," Koeser said.

That is a problem many towns would love to have. Taxable sales in the first quarter of 2005 for the city were up 28 percent, mostly attributable to new oil money. Koeser, who himself owns a wireless communications company, said his business, "has probably been as good as it's been since that first boom that we had."

The b-word

But Koeser committed a bit of a faux pas in calling the current climate a "boom."

The term makes longtime residents of the region nervous about an ensuing bust. In politician-speak, Koeser corrected himself, "I like to use the term that we have a strong upturn in oil activity."

Is it really a boom? Looking at the growth in production, one could only assume as much. "I don't know what their alternative term for it is, but activity level is very, very high. We're at 28 rigs, and we have not been there for a long, long time," Helms said.

But the number of rigs in Montana and North Dakota is still not up to the levels of the last boom, like in October 1981 when North Dakota had 187 rigs. Neither is employment as high. And even if growth continues, the regional industry is not likely to reach previous highs in rigs or employment, at least anytime soon.

That is due to a new technology called horizontal drilling, introduced to the district in the last 20 years. As the name implies, horizontal drilling allows oil rigs to drill sideways and reach wells much farther from the site of the rig than traditional techniques allow.

The new technology means that about four times more oil can be extracted per rig. About 85 percent of new well permits are for horizontal wells. And fewer rigs means fewer roughnecks.

One of the benefits of the new technology is that it has taken pressure off an already strained labor market. This also means that if a bust does come, the effects won't likely be as dramatic as in years past.

Exactly what constitutes a boom isn't a matter of scientific fact, but the term has a psychological impact. Oil prices are notoriously volatile, and as a result the industry is also cyclical. "Historically, we have experienced three or four booms in the Williston Basin, and each one of them was followed by a really major retraction and a bust. I think that people's feelings are that at some point oil price is going to temper demand growth and that we're going to see oil prices drop, and they're hoping they don't drop precipitously and that we can make a soft landing. We never have yet, so I think that's their concern," Helms said.

These cycles become vivid with a look at charts of oil prices, production, producing wells and employment in the region. But residents of the region don't need to look at data, they remember the past.

The city of Williston itself is a good case study. It currently has about 14,000 residents, but in the early 1980s, at the height of the last oil boom, the population was 17,000.

After the price of oil dropped, the residents fled, and so did businesses and developers, leaving behind an array of unfinished developments. The city ended up with about $20 million in special assessment debt for the properties it had to take over.

That debt is now paid off, thanks in part to a municipal sales tax the city levied. The upside is that it now owns a large number of partially finished properties it can have developed, assuming the present boom continues.

Prospects

Even if the region is in the midst of a boom, there may be no need to worry about a bust at all. That's what some analysts think at least. Different forecasts make different predictions, but they're all predicting relatively high oil prices for the foreseeable future. "What they're telling us is that they're expecting those crude prices to stay above $30 a barrel for 20 to 25 years. That's kind of the worst-case scenario," said Helms.

To Helms, a worst-case scenario means the lowest prices; consumers may beg to differ. But this projection is the conservative estimate because it is based on the 20-year average price of $35 a barrel, not the current higher prices.

A major factor in this picture is the same factor that helped cause the original surprise: enormous growth in world demand, due in part to China and India. Development in those countries is changing the world market. Changes in the market make prediction more difficult, and, of course, forecasting future oil prices has never been easy.

So Koeser and others are hedging their bets. "I think the reality of it is that you need to take advantage of the increased activity and benefit from it and build your community and build your infrastructure, but I think it's important to realize that there's no guarantee that five or 10 years down the road, that that economy will be the same," he said.

No guarantee, perhaps, but at least for now residents are ecstatic over record high oil prices.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.