Jonathan Lindstrom keeps a watchful eye on Twin Cities housing prices. He and his partners at the Jonathan Lindstrom Real Estate Group saw the price of homes in exclusive areas of St. Paul and Minneapolis climb upward of 18 percent per year just a couple of years back. "We really saw some unprecedented growth in prices in the late '90s and early on in this decade," he said.

But the vagaries of any housing market can cause changes pretty quickly. Recently, advancing mortgage rates and an available housing stock that well exceeds demand have resulted in a more modest level of price appreciation. "You're still seeing some houses that were purchased around 2002 coming back on the market 5 to 12 percent higher than the previous sale price, but as a whole we just aren't seeing the kind of huge price jumps that we witnessed just a few years back," Lindstrom said. But housing values continue to rise nonetheless. As of August, median home values rose 7 percent in the Twin Cities over the last year, according to the Realtor Public Policy Partnership in St. Paul.

The Twin Cities was not alone. Housing prices throughout the Ninth District have been climbing steadily for the last decade and a half. While chic locations and increasing size of new homes help push prices higher, larger macro factors like mortgage rates, available housing stock, economic vibrancy and even regional amenities play major roles over the long term. There also was a considerable amount of variability in growth rates among individual states and especially their metropolitan areas, much of which can be traced to the relative importance of these macro forces in individual cities.

Since 1990, the price of the average single-family home in Minnesota, Montana, South Dakota and Wisconsin increased faster than the national average (which itself almost doubled during this period) according to housing price index figures published by the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO). Only North Dakota's 79 percent hike fell short of the national benchmark (see Chart 1). However, for much of the period the price of the average single-family home in North Dakota actually outpaced the national average.

Sources: Office of Federal Enterprise Oversight,

Housing Price

Index Q1 2004; Mortgage Bankers Association; author's calculations

The dynamics of housing appreciation changed across the board around 2000. When mortgage rates began their steady descent in 2000—bottoming out around 5.1 percent in June 2003—home prices spiked nationwide, but more so in the nation's more populous and land-constrained coastal states than in the district. For example, Rhode Island experienced an 80 percent increase in housing prices over the last five years, while California was close behind at 77 percent In contrast, Minnesota registered the sharpest increase among district states during this period at 56 percent and also was the only district state to surpass the national average of 42 percent for the last five years (Chart 2). Even with that aggressive climb in recent years, the national level of price growth is still less than the other district states for the entire 14-year period.

*Based on 1-year data

Source: Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, Housing Price Index Q1 2004

Appreciating castles

While statewide statistics provide a good first read on broad housing price changes over time, they also tend to hide a lot of diversity.

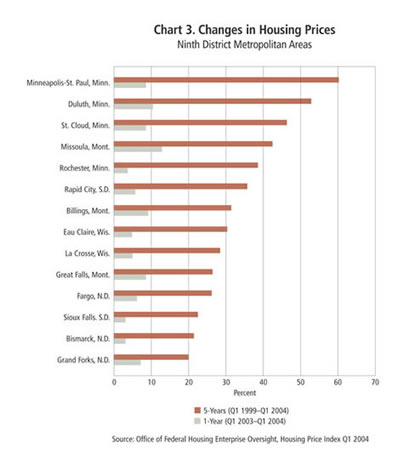

Metropolitan areas in the district display a fairly wide range of housing price appreciation over the last five years (Chart 3). A closer look at the dynamics behind metro price increases reveals that housing price appreciation (or lack thereof) can be traced to the presence (or absence) of various demand and supply factors like growing populations, healthy economies, natural and cultural amenities, and constraints on housing supply.

A healthy 35 percent price increase in Rapid City, S.D., over the last five years may surprise an outsider, but it comes as no shock to Rob Miller, director of equalization in Pennington County. He noted via

e-mail that Rapid City's beautiful environs and proximity to the Black Hills and Mount Rushmore vacation area and the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally have drawn many people, especially retirees, to settle in the area. In spite of "brisk "construction activity, Miller said, demand for new and existing housing has far outstripped supply.

The allure of natural scenery and outdoor recreation has attracted newcomers to other district metropolises as well. Over the last five years, housing prices in Missoula, Mont., have increased more than 42 percent, including a district-high 13 percent in the last year alone. From his office—complete with a bucolic view of grazing elk—Peter Hance, executive director of the Missoula Housing Authority, said amenities draw people to Missoula and generate heavy demand for housing. The city's population swelled nearly 22 percent during the last decade-many relocating from nearby Rocky Mountain states and more expensive Pacific Coast locales like California. "Missoula offers relatively low wages and salaries, but the quality of life more than makes up for it," he said.

Both Hance and his wife accepted substantial pay cuts and now pay more per square foot for housing than they did in also-pricey Essex, Conn. From his perspective, their move to this attractive Western conurbation was well worth it—citing the surprisingly pleasant winter weather (situated west of the Continental Divide, Missoula dodges the arctic cold fronts that blast much of the district), a vibrant downtown, a multitude of cultural offerings, lack of humidity and pesky bugs, and the wildly popular University of Montana Grizzlies football team.

Seeking to preserve this quality of life in the face of a rapid population influx, Missoula has taken steps to influence the pattern of growth and protect parcels of land from private development. Through its Urban Open Space Plan, the city has already purchased and set aside over 3,000 undeveloped acres for scenic preservation, bicycle and hiking trails, parks and recreation fields. While popular with many residents, the plan limits the amount of land available for new housing development, putting upward pressure on the city's housing prices.

Minneapolis-St. Paul saw housing prices rise more than 60 percent in the last five years. Like Missoula, the Twin Cities offers residents considerable quality-of-life perks, like an active arts scene and professional sports teams. But a major driver of housing appreciation here appears to be strong employment opportunities and relatively high levels of disposable income.

Glenn Dorfman, chief operating officer and lobbyist for the Minnesota Association of Realtors, notes that the state of Minnesota—and the Twin Cities metro in particular—enjoys a diverse job base and a comparatively large percentage of workers employed in high-skill, high-wage occupations in companies like 3M, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, General Mills, Northwest Airlines, Target and Wells Fargo. The University of Minnesota, one of the nation's top public research universities, also attracts highly skilled students, faculty and researchers to the area.

With a greater concentration of "brain power" industries like biomedical devices and finance, Dorfman said, the state relies less on older industrial sectors than surrounding states like Wisconsin or Michigan. It has also helped push up wages: Per capita personal income of $37,787 in the Twin Cities in 2002 was good enough for 17th place nationally, ahead of larger metro areas like Los Angeles and Chicago.

Because of strong employment and income growth, the Twin Cities has been a magnet for newcomers. Between 2000 and 2003 alone, the area added 46,000 households and almost 100,000 people—roughly equal to the entire population of Duluth, Minn. Local population watchers believe the metro area will add 1 million residents and a half million households over the next 25 years, continuing long-term demand for housing.

Bubble trouble?

Many believe that the sustained boom in housing sales and rising prices nationwide have helped to prop up the otherwise lethargic national economy. Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies estimates that housing wealth effects stemming from price appreciation, realized capital gains and heavy home equity borrowing have contributed more than one quarter of the growth in personal consumption spending in both 2002 and 2003.

In the long run, housing prices should move pretty much in line with incomes. A growing U.S. gap between housing prices and pocketbooks has fueled speculation about a bubble and the possibility of a major downward price correction.

Economists (including several from the Federal Reserve System) have used historical data, price-to-rent ratios and other indices to show that the risk of a nationwide housing bubble popping anytime soon is very slight. They note that recent price levels are in line with low mortgage rates and the growth in personal income registered through the 1990s.

These same experts do note, however, that price levels in some regional markets around the country may not reflect underlying property values, as determined by both the micro and macro real estate pricing fundamentals outlined above. History shows that when speculative price levels crash head-on into a sizable negative economic shock, falling prices are likely to follow.

According to a 2002 article in the Wall Street Journal, after home prices increased 89 percent and incomes only 37 percent in Los Angeles in the late 1980s and early '90s, prices tumbled nearly a quarter over the next five years when defense industry cutbacks triggered a local recession. A similar bubble deflated in Boston in the late '80s, when a technology downturn damaged the city's employment situation and prices decreased 11 percent over just a two-year period.

While alarming, these coastal horror stories aren't likely to be duplicated in the district. For the most part, income in the Ninth District's metropolitan areas has kept pace with housing prices. Chart 4 displays a simple, if crude, measure of housing affordability that looks at OFHEO's housing price index compared with annual per capita income. The relative change over time displays the manner in which growth in housing prices is matched by a growth in income (a horizontal line would reveal that both have increased at an identical rate).

Sources: Office of Federal Enterprise Oversight;

Bureau of Economic Analysis; author's calculations

Each metropolitan area has charted its own unique course while still maintaining a somewhat consistent relationship with the nationwide trend. Most cities weigh in somewhere between 90 and 110 for the period, indicating that increases in incomes and housing prices are correlated fairly closely and, by extension, the average single-family home has remained affordable—especially as mortgage rates remain historically low.

In spite of considerable population growth and stable economies, cities like Fargo and Bismarck, N.D., Rochester, Minn., and Sioux Falls, S.D., have income gains that actually exceeded housing appreciation. Strong employment bases and little constraint on housing supply have kept affordability largely in check.

Since 2000, however, rising prices have cut into affordability across the board. By 2002, more than half (eight of 14) district metros were seeing housing prices rise faster than income; the worst hit have been Missoula, Duluth, Minneapolis-St. Paul and Rapid City.

In Montana, a state where per capita income ranked 44th in the nation in 2003, Missoula's homes have appreciated at rates similar to many Pacific Coast hot spots. A 2003 study by the Center for Policy Analysis and Community Change in Missoula found that less than half of the city's households could afford to buy the average-priced home; nearly three-quarters don't earn enough money to purchase a new house. While housing values increased 31 percent between 1997 and 2001, incomes rose just 6 percent.

Despite "one of the most active Section 8 housing programs in the country" and a full portfolio of homebuyer assistance programs, Hance said the Housing Authority simply can't keep up with the widespread need for housing assistance. Limited funding means the organization can help only a few. Those who are eligible for the programs are often still unable to find a home that they can afford.

"Small, 800-square-foot homes in Missoula sell for $180,000 to $200,000. If you're making $8 an hour, you may qualify for a mortgage of $120,000. With a gap of $60,000 to $80,000 per family, our funds are depleted very quickly," Hance said.

If the economy picks up and interest rates rise to stave off inflation, first-timers in Missoula and elsewhere are likely to see little relief-that is, unless housing prices moderate and stabilize long enough for incomes to do some catching up.

Outlook: sun not the only thing rising

Barring substantial economic shocks or a manic spike in mortgage rates, district housing markets don't appear at risk for sliding prices. Even in those areas facing growing affordability issues, local real estate experts don't foresee a bubble forming or popping anytime soon.

Hance believes that demographic forces will help sustain housing demand in Missoula. He notes that the need for senior housing far outstrips supply at a time when many baby boomers are nearing retirement. The city's smart growth policies and other regulatory barriers to sprawl will also keep a lid on supply and sustain pressure on prices. "Everyone is talking about a housing bubble, but I just can't see that happening. There are too many factors that will continue to push prices higher," he said.

While the Twin Cities housing market remains red hot and prices continue to rise more than 8 percent annually, the winds of change are blowing. The area's Realtor Public Policy Partnership reported that pending sales increased only 1.1 percent in June of this year and actually decreased by 9 percent in July. Consensus is also emerging among real estate professionals that builders may have overshot demand in the near term—the number of listings has continued to grow, but the number of buyers has remained fairly stable. While a normal seasonal slowdown may be a factor, recent activity has led some to speculate that the market may be offering its first sign of moderating.

Rather than signaling the collapse of a bubble, however, lower rates of housing appreciation would instead provide a welcome sign that the market is simply settling gently into a pattern of more sustainable growth, according to both Dorfman and Lindstrom.

"As long as the economy is robust, houses will retain their values and continue to appreciate, although I believe that the current gold rush days of 10 to 12 percent increases per year will soon fade. As rates inch upward and supply and demand start to equalize, appreciation in much of the metro area should return to the historic average of 2 to 3 percent increases over a 50-year period," Dorfman said.