When the Federal Open Market Committee announces a change in its target for the federal funds rate, the news reverberates not just through financial markets but through the broader economic and political landscape as well.

National banks raise or lower their prime rates, prompting similar movements in mortgage and consumer credit rates in the following weeks. The stock market may rally or retreat, depending on whether the FOMC's move matches Wall Street's expectations. Pundits at investment banks and on TV financial shows weigh in with their economic prognostications and speculate whether the Committee will boost rates again or stand pat at its next meeting. This fall, consecutive FOMC directives raising the federal funds rate ceiling even became grist for deep analysis of the presidential campaign. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan's justification for rate increases—the economy was well on its way to recovery, despite a "soft patch" in June—was believed to buoy George W. Bush's election prospects while hurting those of challenger John Kerry.

Amid all the tea-leaf reading and excitement, a simple fact is usually lost on the public when the FOMC makes a rate announcement. Media reports give the impression that the Fed literally sets the federal funds rate, the rate charged on overnight loans between banks, by governmental fiat: Greenspan speaks, and a new interest rate becomes the law of the land, it seems, like the Interstate speed limit or Atlantic fishing quotas. But in fact, when the federal funds rate shifts, it's not because Greenspan and the 12 voting members of the FOMC said so. At its meetings the Committee announces a target for the federal funds rate and the Fed then strives to hit that target by managing reserve balances—money that banks hold in reserve rather than lend to customers.

The Fed wields this key tool of monetary policy through a process called open market operations. By adding or draining reserve balances, it meticulously adjusts the federal funds rate, directly influencing the cost of credit and by extension, the performance of the U.S. economy. A higher rate tends to inhibit economic growth by increasing the cost of money; a lower rate fosters economic expansion by making credit more readily available.

Open market operations are a complex balancing act played out not just after the FOMC announces a federal funds rate target, but every business day. Trying to maintain a constant rate—or alter it by exactly the required degree—is like trying to shoot an arrow into a bull's-eye while walking a tightrope. Myriad factors, many of them outside your control, conspire to throw off your aim. Changes in borrowing and lending patterns in the money and capital markets, seasonal swings in demand for currency, fluctuations in U.S. Treasury cash balances at the Fed, severe weather that disrupts check processing—all can affect reserve balances and cause daily peaks and valleys in the federal funds rate.

Yet so effective is the open-market process that it's hardly surprising that when the FOMC issues a directive, the financial community and the press treat it as a fait accompli, a done deal. In reality, the relatively steady rate that prevails between meetings depends to a large extent on the actions of staff at the New York Fed and the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C. This article takes a behind-the-scenes look at open market operations, the Fed's big stick of monetary policy that, for all its power, is often taken for granted.

Putting on the pressure

The Fed influences the economy through the banking system's demand for reserves. Commercial banks and thrift institutions have no choice in the matter; under the Monetary Control Act of 1980, the Board imposes a minimum reserve requirement of up to 15 percent on transaction deposits—typically checking and other accounts from which transfers can be made to third parties. The current reserve requirement on the bulk of transaction deposits above regulatory thresholds is 10 percent.

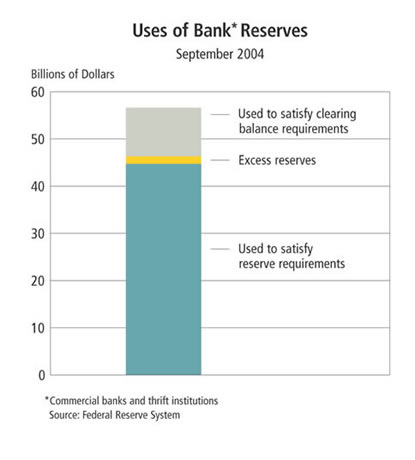

Required reserves held either in the vaults of depository institutions or as deposits at district banks amounted to about $45 billion as of September (see chart). Another $1.6 billion in reserves were excess reserves—funds above mandatory minimums, set aside by banks as an extra cushion against deficiencies. In addition to required reserves, depository institutions also may contract (or be required) to maintain clearing balances with district banks. In September about $10.2 billion in reserves was earmarked to pay for Fed services such as check clearing and wire transfers.

Reserves flow continually among banks as they process transactions and strive to maintain minimum required reserves and clearing balances (since money that nobody borrows can't earn income) while avoiding costly penalties for deficiencies. The federal funds market acts as a clearinghouse for these reserves. When banks and thrifts try to borrow from each other more reserves than are available in the market, they bid up the federal funds rate—the interest rate that financial institutions pay on overnight loans. A rising federal funds rate in turn drives up other interest rates: corporate bond rates, discouraging investment in new equipment or plant expansions; mortgage rates, depressing demand for housing; and auto and other consumer loans, dampening overall consumption. Higher interest rates also increase the real or perceived risk of loans, tightening the purse strings at banks. And they lower the value of assets such as stocks and bonds, sapping the net worth of households and businesses.

In contrast, a dropping federal funds rate—the result of plentiful reserves in the federal funds market—lowers the cost of credit, fostering increased investment and boosting asset values. Thus a rate swing of just a quarter of 1 percent—25 "basis points" in financial parlance—can quickly modify the credit environment, with profound short- and long-term consequences for the economy.

By applying pressure to reserve balances, thereby nudging the federal funds rate up or down, the Fed can either reinforce or counteract the cyclical rise and fall of interest rates, modulating the economy's rate of growth. Ideally, monetary policy fosters stable prices that promote long-run, sustainable economic growth.

The Fed has other monetary policy tools at its disposal aside from open market operations. It can also adjust reserve requirements and rewrite terms for borrowing from the Federal Reserve discount window, the last resort for banks that can't satisfy their reserve obligations in the federal funds market. But these methods of influencing reserve levels aren't used as often as they were in the past. Over the last 15 years the Fed has hesitated to raise historically low reserve requirements because they impose a cost on banks—forgone interest on $10 out of every $100 deposited by account holders. The last time reserve mandates changed was in 1992, when the rate on transaction deposits was cut, from 12 percent to 10 percent. As for borrowing from the discount window—at one time an actual window at district banks, where banks dropped off collateral for loans—the practice has declined in the last decade, partly because of increased clearing balance requirements but also because of public perception that borrowing from the Fed is a sign of weakness.

That leaves open market operations as the Fed's preferred method of influencing short-term interest rates. The Domestic Trading Desk at the New York Fed, in consultation with Board staff, conducts open markets operations by buying and selling previously issued U.S. government securities. Known as an "open market," because securities dealers that the Fed conducts business with compete with each other on the basis of price, the U.S. Treasury securities market is the broadest and most active of U.S. financial arenas, trading over $480 billion every day.

When the Desk buys securities, it increases the amount of reserve balances in the system available to banks, lowering the federal funds rate. Selling securities has the opposite effect, draining reserves and driving up the rate. The Desk relies on the same mechanism to make daily micro-adjustments in the rate once the target is reached, offsetting market and technical forces that may push credit conditions off target.

A call to arms

The FOMC's decision to raise or lower its target for the federal funds rate, or let the current rate stand, is the culmination of exhaustive research on economic conditions and monetary strategies by the Board of Governors staff and experts at all 12 district banks.

Committee members meet in Washington, D.C., every six or eight weeks to consider the contents of the "Greenbook," a distilled forecast for the U.S. economy; the "Bluebook," an analysis of various monetary policy options; and the "Beige Book," a discussion of regional economic conditions prepared by each district bank. At the end of the day, FOMC voting members—seven Board members, the president of the New York Fed and four district bank presidents who serve one-year, rotating terms—arrive at a usually unanimous decision, setting a fresh federal funds market cycle in motion.

Securities dealers, investment bankers and others in the financial community eagerly await the Committee's decision. Business plans, profit margins and careers hang on how Wall Street reacts to a new monetary policy directive and the inevitable changes in interest rates and overall economic growth. Prior to 1994, changes in the Fed's monetary posture weren't announced until the next FOMC meeting. Weeks of speculation and attempts to divine the Committee's intentions from Trading Desk activity ensued. Nowadays the FOMC keeps the suspense mercifully brief, announcing its target for the federal funds rate immediately after the meeting, together with a concise rationale for any changes in policy. The Committee may also announce changes to discount window rates.

For the Trading Desk at the New York Fed, the Committee's directive is a call to arms. Putting their heads together with counterparts at the Board, the Desk's forecasters and analysts develop an action plan for hitting the federal funds rate target, expressed as a "reserve path"—the trend that total available reserves must follow over the coming weeks to achieve the designated interest rate. Comparing this path, based on detailed forecasts of reserve demand, with daily projections of reserve supply determines how much money the Fed must pour into or drain from the banking system. Thanks to its $690 billion portfolio of Treasury and federal agency securities, the Fed is in an excellent position to expand or shrink reserve balances, the portion of reserves held on deposit at district banks. About 30 primary dealers in the U.S. Treasury securities market work with the Trading Desk to ring daily changes in the volume of reserve balances available to banks.

When it wants to increase reserves, the Desk buys securities and pays for them by making a deposit to the account maintained at a district bank by the primary dealer's bank. In effect, the Fed writes a check on itself, increasing the aggregate volume of reserve balances in the system. To reduce reserves, the Desk sells securities to a dealer and collects money from that account, drawing down the total volume of reserves. In an open market, the law of supply and demand drives the process: The Desk accepts the lowest offers for purchases and the highest bids for sales until enough dollar volume has been traded to make the desired impact on reserve levels.

Most of the time, the Desk engages in transitory trading designed to add or jettison reserve ballast quickly, to keep average reserve levels on the prescribed path during two-week reserve maintenance periods. Short-term repurchase agreements (RPs or "repos") temporarily pump up reserves; dealers sell securities to the Fed, agreeing to repurchase them on a specified date at a specified price. When the RPs mature, the added reserves automatically disappear. Alternatively, the Desk executes reverse repurchase agreements (RRPs or "reverse repos"), which have exactly the opposite effect of RPs, temporarily lowering reserves. Instead of buying securities, the Desk sells them, promising to buy them back later at a specified price. If the Desk expects reserve shortages or excesses to persist, it can buy or sell government-backed securities outright. These much less frequent trades effectively add or drain reserve balances permanently.

All these reserve balancing and counterbalancing transactions are consummated in a matter of minutes. The Desk executes RP and RRP trades by sending an electronic message to all its primary dealers, requesting securities bids or offers within 15 minutes. In about five minutes the deals are done; the Desk accepts the most attractive bids or offers and rejects the rest. Outright trades take a little longer—about half an hour for dealers to respond and 15 minutes for the Desk to make its selections.

Walking a high wire

Making trades is the easy part of open market operations; the hard part is hitting the reserve path—figuring out how much to either boost or decrease reserves to attain the targeted federal funds rate. Open market staff in New York and Washington spend each business day walking a high wire, gathering and analyzing data from a multitude of sources in an attempt to bring actual reserve levels into line with demand for those reserves during a given maintenance period. Striking just the right balance is a dynamic, delicate process complicated by the vicissitudes of the economy. Reserve estimates, especially on the supply side, can be subject to wide margins of error, and they're continually being updated as fresh data come in.

Demand for reserves constantly ebbs and flows in sync with fluctuations in checkable deposits. Short-run changes in interest rates, tax payment and payroll cycles, and seasonal variations can all affect the amount of money held in U.S. checking accounts. Open market staff estimates reserve demand (all reserve uses minus anticipated levels of borrowing from the discount window) based on underlying deposit trends and average required reserve ratios for small and large banks. As projections for reserve demand are revised, so is the reserve path.

Coming to grips with reserve supply is even more problematic because forces beyond the Fed's control influence overall reserve levels. These "autonomous factors" are subject to their own swells and troughs, driven by developments in the United States and overseas. For example, the amount of currency in circulation—about $690 billion in the third quarter of this year—affects how much money banks have to lend to each other to meet reserve demands. When businesses and consumers hold more cash, bank deposits and reserves fall. The amount of paper currency and coin in people's pockets fluctuates, depending on the day of the week, the season (cash in hand rises substantially during the year-end holiday and vacation shopping season) and the level of demand for U.S. currency by foreign governments and central banks. In 2003 the amount of currency in circulation varied by as much as $3.1 billion a day.

U.S. Treasury balances, the accounts the government maintains at the Fed to make and receive payments, also strongly influence reserve levels. Increases in these balances—from tax revenues, for instance—absorb reserves by draining funds from banks and thrift institutions. Because of wide variation in Treasury balances—the maximum daily swing in 2003 was $3.6 billion—it's difficult to estimate their effect on available reserves. Other wobbly supply factors that the Desk and Board staff track from day to day include transactions by foreign central banks and reserve float.

Morning is crunch time at the Trading Desk in New York, as the staff tries to home in on a moving target, finalizing the game plan for securities trades that day. Beginning at 7:30 a.m., analysts check the actual federal funds rate and scan news headlines, economic data releases and updates of securities trading around the world to get a sense of the market forces acting upon it. Forecasters estimate reserve demand and supply, recalculating if necessary to account for late-breaking data on checkable deposits, discount borrowing and other factors. At 9 a.m. the Desk places a conference call to the U.S. Treasury to assess trends in Treasury balances at the Fed and adjust them if necessary. About 20 minutes later the Desk manager reviews the program for the day—how much reserve balances to add or drain—with Board staff in Washington and one of four voting bank presidents from outside New York on the FOMC. After this brief conference call, it's time to clear the decks for action in the securities market. The trading area is a far cry from the Desk of the pre-computer age, where as recently as the early 1990s staffers kept track of securities prices on chalkboards. Today a computerized processing system does the grunt work of executing transactions with primary dealers.

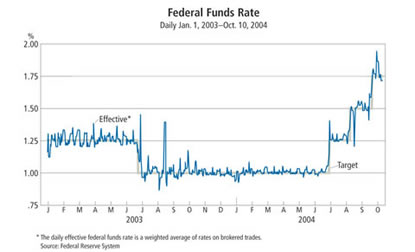

How well do open market operations perform their daily balancing act? Quite well, considering the inherent mutability and uncertainty of financial markets. Over the last two years, the effective (average daily) federal funds rate has faithfully shadowed the target rate, with only a few brief departures from the path laid down by the FOMC (see chart below). In 2003, the median daily deviation from the target rate was just two basis points, or one-fiftieth of a percentage point. But the effective rate's steady pulse does spike or dip occasionally. Deviations can occur at month and quarter ends, as financial institutions settling their books hold on to or release more or less reserves than anticipated. And market disruptions can cause temporary reserve imbalances, throwing the federal funds rate off target. The East Coast blackout in the summer of 2003 cast a fog over payment schedules, contributing to a rate spurt of 35 basis points on Aug. 14.

Of course, widespread speculation about upcoming FOMC action helps the open market staff hit its target. Even before the Committee announces a new federal funds rate objective, the rate starts leaning in that direction as banks, futures traders and other players try to get a jump on the market. The toughest days for the Trading Desk and Board staff come just before an FOMC meeting, when the current rate must be restrained from moving to a different level of its own accord.

Open to change

The machinery of open market operations is constantly being tweaked to keep pace with an evolving U.S. economy. Twenty years ago, for instance, discount window borrowing was a major factor in assessing reserve demand, but since then it has become less important as discount borrowing has steadily slipped. Despite a quarter-point drop in the primary credit rate (the rate paid by banks in financial good standing) to 2 percent in June 2003, average daily discount borrowing last year was $35 million, down from $54 million in 2002 and $78 million in 2001. Figurative trips to the discount window are likely to enter even less into the Desk's calculations in the wake of an FOMC policy change last year that sets the primary credit rate above, instead of below, the federal funds rate, encouraging borrowing only to meet short-term, unforeseen needs.

The impact of check float on reserve supplies will also slowly fade in the years ahead, potentially improving the accuracy of reserve forecasting. The Check 21 law enacted by Congress this year gives digital images of checks the same legal standing as paper originals, allowing banks to transmit checks electronically and slashing the time needed to clear checks through the district banks. Once the necessary equipment is installed, most checks will clear within 24 hours. That will greatly reduce daily variations in reserve float (up to $6.7 billion in 2003), currently a wild card in estimating the supply of reserve balances.

Other possible changes in open market operations are harder to predict, dependent as they are on changes in Fed monetary policy. How and why the FOMC sets a target for the federal funds rate is a topic beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that the mechanics of the U.S. economy change over time, prompting different approaches to achieving both price stability and sustained growth. In the early 1980s, concerned about spiraling inflation, the FOMC directed its staff to tightly control reserve supplies while letting the federal funds rate float freely over a wide and flexible range. But later in the decade when the relationship between reserve supplies and key economic variables broke down, the Committee chose instead to try to control the federal funds rate.

That has remained the focus of open market operations ever since, guiding the type and frequency of securities transactions by the Trading Desk. But in the future, when different economic conditions prevail, the FOMC may devise other ways to exert control over reserves and keep the economy humming along. Whatever monetary policy goals the Committee pursues, chances are good that open market operations will continue to play a vital role in achieving them.

This article is based in part on an Aug. 19, 2004, presentation by Warren Weber, Minneapolis Fed senior research officer, to the Minneapolis Fed's board of directors.

Additional ReadingMore on open market operations, refer to the New York Fed's Web site. An insider's perspective of the FOMC, "Come With Me to the FOMC," Basic background on monetary policy and central bank operations. |