In his first year as president of the European Central Bank, Jean-Claude Trichet has delivered several dozen speeches, but a short talk at a Dutch art museum this fall was especially notable, not just for its content but its style—and for what it conveyed about Trichet himself.

Speaking in Maastricht, the 1992 birthplace of the European Union, Trichet didn't refer to interest rates or inflation trends. He avoided the jargon of economics altogether and spoke instead about the cultures of Europe. Son of a literature professor and devotee of art and poetry, he quoted Van Gogh in Dutch, Goethe in German, Ortega y Gasset in Spanish and other scholars in his mother tongue of French.

Speaking in Maastricht, the 1992 birthplace of the European Union, Trichet didn't refer to interest rates or inflation trends. He avoided the jargon of economics altogether and spoke instead about the cultures of Europe. Son of a literature professor and devotee of art and poetry, he quoted Van Gogh in Dutch, Goethe in German, Ortega y Gasset in Spanish and other scholars in his mother tongue of French.

His speech emphasized the importance of cultural diversity, European unity and openness to other nations. And he argued that these elements constitute Europe's modern identity, an identity embraced at a profound level by the ECB.

His message was powerful, certainly, but it was his manner of delivering it—in several languages, in terms suited to the audience, in a nuanced interweaving of national references—that demonstrated what may be Trichet's most essential talent: his ability to communicate and persuade.

Trichet's other skills are also widely recognized, of course. He is known as a pragmatist who appreciates theory, as a man of strong principles but with a willingness to negotiate, as an economist with élan. Appointed governor of the Banque de France in 1993, he established solid credentials as a defender of central bank independence; the politicians he stood up to were so impressed they later backed his appointment to the ECB.

Trichet initially trained to be a mining engineer—as a young man he worked in the coal mines of northeastern France. But after graduating from the elite École Nationale d'Administration, he rose quickly in the realms of French government and international banking. Today, he oversees monetary policy for Europe's most powerful economies, a dozen nations that have adopted the euro as their currency. His abilities will be tested in coming years, as the euro zone enlarges, as member nations chafe at fiscal constraints and as other hurdles arise.

In a mid-September discussion with Minneapolis Fed President Gary Stern at his bank's Frankfurt headquarters, Trichet explains how the ECB intends to face these challenges, and he displays, once again, the gift of compelling conversation.

PRICE STABILITY

Stern: I would like to start by asking about the inflation objective of the European Central Bank which is, as I understand it, around 2 percent but a little less. What I'm interested in is how you think that has worked as a policy matter, but also how it works in communicating with the public more generally in terms of what you're trying to achieve.

Trichet: To understand better our concept of monetary policy one has to meditate a little bit on the very demanding challenge that we had when we started the euro. The euro was a new currency, starting from scratch 1st January 1999. We had promised the people of Europe, and investors and savers the world over, that we would have a new currency which would be at least as credible as the most credible of the ancient currencies.

That was a promise which was made to the people of Europe because they wouldn't see why they should change their currency if it was to trade their national currency for a new currency which would be less credible, less confidence inspiring, less a good store of value and, therefore, conducive to higher medium- and long-term market interest rates. So it was as simple as that. Otherwise, they simply wouldn't want to be on board for this very important, strategic and bold change.

It was also a promise which was made to the economic agents of Europe that their market interest rates, long-term, medium-term, would not increase to incorporate additional inflation expectation differentials and new risk premia that would be associated with a currency which would not deliver the same price stability as was the case before. And as I said, it was a promise which was made to the global investors, treasurers and market participants.

It's clear that for us the introduction of a sense of continuity with those currencies that were at the best level in terms of stability and credibility, and therefore in terms of low level of medium- and long-term market rates crystallizing this level of credibility, was something which was extremely important. And that's the reason why our definition of price stability is in line with the definition of price stability which existed in these economies, among those 11 which were called to merge in the single currency area, which had the best records in this respect and whose currencies had the same "benchmark" yield curve.

So the less than 2 percent definition is our definition of price stability. We are not in a universe of inflation targeting. As you know, we had to clarify that last year because there was some academic guessing that it could mean a band of zero to 2, with a medium point at 1, because they applied a concept of inflation targeting to our own concept. We clarified that it meant less than 2 and close to 2, in the medium run.

And each element is important. "Less than 2" as the definition of price stability to solidly anchor inflationary expectations in the continuity of the best credibility available in the euro area, "close to 2" meaning that we had no complacency towards deflation, and "in the medium run" to remind observers, academics and market participants that we were not shortsighted. We are not targeting a precise level of inflation within 18 months or two years as in some "pure inflation targeting" concept.

That inflation targeting "school" is changing, by the way. I'm very, very happy that the tendency is now to recognize the merits of thinking more in the medium term, which was a main feature of our own monetary policy concept since the very beginning.

The fact is that we succeeded. From day one the euro had the same level of medium- and long-term credibility that existed before in the best currencies of the pack of currencies that we were merging, and we saw no discontinuity between the yield curve of those currencies that had attained the best level of credibility and that of the euro. And at the moment I'm speaking [editor's note: the interview was conducted in mid-September], more than five years afterwards, we are in exactly the same situation. Market surveys confirm that we are credible to deliver on a five-to-10-year basis, in a medium- and long-term perspective, an inflation which would be in line with our definition of price stability, less than 2, close to 2. By the way, it looks like oscillating in the survey between 1.8 and 1.9, so we are really performing a good anchoring in this respect.

Stern: The range can't get much narrower.

Trichet: I mean, it is only a survey, of course. If I compute the average inflation since we started the euro until now, my memory is that we find around 1.95 percent. So again, we are less than 2, very close to 2. And of course, during this period of five years and a half, we had to cope with a number of shocks, including the oil shock. So we have the sentiment that our concept of monetary policy is certainly something which has fit with the constraints we had at the very beginning.

I will conclude only by mentioning the fact that it was really a formidable challenge to succeed in shipping to the euro the best yield curve available in the euro zone without losing one basis point. And I can tell you, because I lived through that experience myself at the time I was governor of the Banque de France. I remember the moment when we discussed with the Bundesbank colleague and other governors, because we had observed in 1997 that the market's understanding, and a lot of academic understanding, was that we would have a yield curve which would be the weighted average of the yield curves available in the future euro area. So that an increase of rates that was decided in Germany, in France and in a number of other countries at the end of 1997 was interpreted as the first move towards this average.

We decided to campaign globally, going to New York, for instance, to say, "No, you don't understand what we are doing. We did that because it was necessary for the sake of delivering price stability in our own economies, but we were not at all trying to join any kind of average. We are the benchmark; it is all the other rates that will fall down." And it is exactly what has happened. The convergence trade had started on the very long-term end of the yield curve and then came progressively to the lower end, and finally all the yield curves of all the different currencies that were called to merge came down and fell down to join the benchmark.

THE EURO

Stern: I agree it's been quite an accomplishment and it sounds as if, with some work, you've managed to communicate to academics, and to the public more generally, exactly how the objective is supposed to work both quantitatively, that is, around 2 but a little lower, but also at the medium term.

I would propose another indicator of credibility, and that is the appreciation of the euro relative to the dollar recently, which would seem to me to suggest that there's a good deal of credibility behind the euro. I don't know if you agree with that, but that seems like an indicator to me.

Another question is, when I was in Paris recently there was some concern at the meetings I was at about the strength of the euro. I don't know if you want to get into exchange rates; that's something we try not to do at the Fed.

Trichet: [laughter] I know that you are being very, very cautious and I will be equally cautious.

I would only say that at least those who very imprudently thought that they could take advantage of the first years to argue that the euro would have a definitive fault line that would demonstrate absence of credibility were wrong. I always said that they were wrong, and they were wrong. For the rest, at the moment we are speaking, I will stick to the last G7 communiqué that I signed in Washington on behalf of the ECB. As you know, it says in particular: "Excess volatility and disorderly movements in exchange rates are undesirable for economic growth."

CENTRAL BANK COMMUNICATION

Stern: Let me pursue the communication topic a little bit further because it's something that, as I'm sure you're aware, we've been struggling with in the Federal Reserve off and on. Certainly over the last 14, 15 months beginning last summer, we've had a lot more concern about whether we've been able to communicate our intentions effectively to the markets and to people in the economy more generally. And we've been concerned, in fact, about how much communication we should do.

Do you have any thoughts on that? I don't have the sense you've had the same difficulties, recently at least, that we've had.

Trichet: Well, several comments because it's a very important question, of course. First of all, when we started the euro under the chairmanship of my predecessor, Wim Duisenberg, we felt immediately the necessity to communicate to the market our analysis of the situation and the reason why we had taken a decision to increase, decrease or leave rates unchanged. We felt it was important not to wait for five weeks or six weeks but to tell market participants, observers and the people of Europe immediately.

Why? Because had we waited for a long period of time, we would have let all kinds of explanations flourish in 12 different cultures, in 10 different languages, with unavoidably some voices that would have been, perhaps after translation, considered self-contradictory inside the system.

So the idea to have joint terms of reference and to give in real time, if I may, immediately after the meeting, the reasons why we had taken a decision, with precise words that would be agreed to by the Governing Council as the introductory remarks of the president, and then to hold—which remains exceptional among the big central banks of the world—to hold a press conference, this was something that we judged in line with the legitimate general call for transparency in our own constituency of central banks and also something which was particularly well suited to the European case, again starting a currency with 11, and then 12, different economies, nations and cultures.

So that has worked, I have to say, pretty well. From time to time we have had some criticism that we were perhaps not sufficiently transparent. We could respond, "Sirs, we started the thing!" We were the first amongst the important central banks of the world to engage in this immediate communication, not only delayed communication, but quasi real time.

The second observation is that in communication with markets and people in general, we try to be as predictable as possible. We display our monetary policy concept, our famous two-pillar monetary policy concept, based on an economic analysis and a cross-check with a monetary analysis, so everybody knows exactly what the underlying concept is. We say what our goal is in arithmetic terms—which is another key element of full transparency—less than 2, close to 2, and everyone knows that we are keen to remain fully credible in the medium and long term in the delivery of that price stability. And that can be checked by objective observations.

So we trust that we give the market a lot of information that permits it to know in advance what we are aiming at, what is our methodology, how we are reasoning, and that gives a good sense of what is likely to happen. In addition to that, I would say that, in any case, I wouldn't like a priori to surprise the market. So if the market would work out expectations which do not fit our own way of thinking, I would not hesitate, as porte-parole of the Governing Council, to correct what could be a wrong interpretation.

By the way, objective measurements of market futures reveal that we have always had a very good level of predictability. Academic research on the period since the start of the euro shows that, to the surprise of some observers, both the United States and the euro area have shown very good predictability, on the same order of magnitude in both cases. On both sides of the Atlantic we want to be predictable and we are predictable.

Stern: And these press conferences that you hold immediately after meetings, those have worked effectively in terms of actually getting reasonably accurate and consistent coverage?

Trichet: Well, the value, of course, of these press conferences is that they permit us to learn, as far as the main issues are concerned, what is in the minds of the European and global press. We have a strong representation of global media, including, of course, of major U.S. media. So in that sense, it is an important way of being up to date. Also it permits the Vice President and me to share the views of the Governing Council and to have simultaneously an immediate communication with the European and global press. And also, as I said before, it provides terms of reference for the full body of a large, diversified, continental system. We are a team: We have the ECB, and we have the system itself with the 12 national central banks, and communication at a national level in the various languages that make up Europe are also, of course, very important.

So that press conference has two goals. One is to communicate in the best fashion possible with all observers, market participants, the media and public opinion at a European-wide and at a global level, and the other is to constitute terms of reference which permit the full body of the European monetary team to speak and communicate in a unified way, in particular all the members of the Governing Council in all the languages of Europe.

And again, one of the things the team tends to be proud of is that with 18 members of the Governing Council, and again 12 different cultures, the degree of unity, the degree of, I would say, a single voice through 18 persons has been reasonably successful.

STABILITY AND GROWTH PACT

Stern: Yes, I think it's been striking. Let me shift gears a little bit and ask about some things that are, I guess, more structural, starting with the Stability and Growth Pact. I gather it is under very active discussion today, and there's some talk about making it more flexible. What's at stake there, and how do you think that might play out?

Trichet: First of all, we consider that our genuine Union, the "EMU," Economic and Monetary Union, has really two sides. There is the monetary union—and we are ourselves of course the operational institution to manage the monetary union—and also you have the economic union.

One of the remarks I regularly heard in the United States over the last 10 or 15 years was that it was extremely bold to introduce a single currency in a political universe where there was no federal government and no federal budget. And I take it that it is a real remark, if I may, which is of course founded in terms of economic reasoning. The Stability and Growth Pact permitted the Economic and Monetary Union to be coherent and stable, and it is our way to respond to this criticism, implicit or explicit, coming in particular from some circles in the United States, on the boldness of introducing a single currency without having a full-fledged federation. We can respond to those criticisms with the Stability and Growth Pact.

So for us it is not a question of being orthodox for the sake of orthodoxy—which is the normal position, of course, for a central bank on both sides of the Atlantic—but overall to deal with this absolute necessity to have a coherent EMU. Of course, that explains why we advocate respecting the Stability and Growth Pact and making it as sound and reasonable as possible.

Now as regards the present debate, it is very much alive, of course. I was participating myself in the last Eurogroup meeting under the chairmanship of Gerrit Zalm, the Dutch Minister of Finance. The point I made there on behalf of the Governing Council of the ECB was that we saw absolutely no harm in—on the contrary, we were prepared to back—improvement in the implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact with a better understanding of the preventive arm of the Pact.

The Pact has two arms; one is prevention and the other is correction. On the preventive arm of the Pact there are proposals made by the Commission which we trust go in the right direction, taking account of the economic cycle much better, taking account of the structural aspects of the various economies concerned, defining in the best fashion possible what should be the "close to balance or in surplus" that is called for by the Pact, and creating or enforcing incentives to behave as properly as possible in the good times to put aside what would be necessary for the bad times.

So in these areas I would say that the ECB Governing Council feels comfortable with a number of proposals. Depending of course on the final result because the decision is taken by the Council of Ministers of Finance, and we have only a proposal of the Commission. So I reserve our final point on the precise proposals for the decision after discussion with the Council, but again we a priori feel comfortable with it.

Where we are not comfortable is when there is a call for loosening the corrective arm of the Pact. We really trust ourselves that the nominal anchor of the 3 percent [of GDP limit for annual budget deficits] should not be touched. Because of all that I have said about cohesion in the EMU without full-fledged federation, we consider, in particular, that loosening the definition of "exceptional circumstances" [in which a member nation can exceed the 3 percent limit] would not be advisable. And also that loosening the sequencing for correction, the timing of the correction would not be appropriate.

More generally we say let's not change the Treaty—fortunately nobody asked for a change of the Treaty—let's not change the regulation. In the domain of the corrective arm of the Pact, let's apply it in the most economically rational way, which means putting aside in the good times what will be necessary in the bad times.

That is the message I made publicly on behalf of the Governing Council. I made it during the discussion with the Eurogroup and we will see how things go. In any case we are giving our own view, which is based on our responsibility to run a monetary union in the best fashion possible. The final decisions are taken by the college of the executive branches of Europe and, again, it is our duty to give the Council of Ministers our views as clearly as possible.

Stern: It's similar to Chairman Greenspan testifying about the U.S. budget deficit and trade deficit, which of course is another topic that has garnered a lot of attention in the United States. Is there a lot of interest in that topic here?

Trichet: I think so. I think that from that standpoint we are calling on both sides of the Atlantic for soundness.

Stern: It's easy to call for, but it's not always easy to achieve.

Trichet: Sure. It is certainly difficult and on both sides of the Atlantic the final decision will be made by the executive branch and the parliament.

THE LISBON REFORM AGENDA

Stern: That's right. Let me ask another structurally related question, pertaining to the Lisbon reform agenda. How do you feel about progress on that front and what might you see going forward?

Trichet: First of all I would say that embarking on bold structural reforms is a very important issue in Europe. We have assets and liabilities on both sides of the Atlantic. And we would agree in the G7/G8, that the assets of the United States are the fantastic flexibility of its economy, its bright capacity to adapt to new circumstances, to weather shocks and to develop productivity progress. And its big liability is an insufficient level of savings.

On our side of the Atlantic, it would be the contrary. Our asset is that we do not have a savings problem; on the contrary, I would say that we are able to easily finance our own investment with our own savings. But we have a problem of structural reforms. The economy is not sufficiently flexible, doesn't develop sufficient productivity progress, is not sufficiently resilient because it's not appropriately flexible.

So, concentrating on this side of the Atlantic we agree on a diagnosis which is enshrined in what we call the Lisbon agenda, which was agreed upon by all Heads of State and Governments, all executive branches of Europe, in Lisbon in 2000. The diagnosis is there. The goals are there. And at least in principle the orientation is not disputed. We all agree on what is necessary, executive branches, the Commission and, very strongly, the ECB and the Eurosystem.

Solving the problem is more complex, for a number of reasons. First, a lot of what is in the Lisbon agenda depends on national implementations and national decisions, so while there is a joint understanding and a joint diagnosis, for a large number of areas in which progress must be made, there is no effective machinery to collectively decide and implement.

In a certain number of domains, such as pursuing the achievement of the single market, we have the European Union machinery. But when we have to deal with the labor market flexibility, when we have to manage the social protection area or optimize education and research, we are in a universe where a lot depends, as is normal, on national decisions. That is my first remark.

Second remark: We have in a number of domains an absence of sufficient understanding, it has to be recognized, of the general population. Public opinion has difficulty seeing why everybody would be better off if we would make those reforms that have an apparent immediate cost and are delivering their benefits—growth, job creation-over time.

From that standpoint, clearly, we have a challenge of communication, explanation, pedagogy, to convince the public opinion of Europe that if we want to grow faster, it is necessary to increase productivity; if we want to create more jobs, it is necessary to have flexible markets, to reduce unproductive spending and to foster science and technology.

That is one of the main challenges we have. You can see in those countries that are courageously going in the direction of implementing the Lisbon agenda at a national level, how pedagogy and communication is crucial.

So I consider that we all have a share of responsibility in this domain of explaining to the general public why it is appropriate, and that is the reason why I don't exclude the ECB from that. It seems to me that we share that view, on both sides of the Atlantic. The call for flexible economies is also very much in the speeches of Chairman Greenspan and the members of the Open Market Committee. So I take it that we share that view, and we try on our side of the Atlantic to timelessly explain why it is important—even if it is not our own direct responsibility. Our responsibility is delivering price stability.

One of the best tools perhaps we have to convince people is to stress the excellent behavior of the economies which are ahead of others in Europe in terms of structural reforms, like Ireland for instance. They are more prosperous; they have more growth and less unemployment. This idea of benchmarking the structural reform exercise on best performers is promising.

Indeed, if we have an understanding amongst Europeans that a structural reform which has been achieved in one of our economies with a large consensus of political and union sensitivities is largely recognized by academics to have delivered jobs and diminished unemployment, then we could reverse the burden of proof and ask all others, "Why don't you introduce that? It's been tried, it works and it was on the basis of a consensus." It's easy to say, it is more complicated to deliver, but it is probably one of the avenues that we should follow.

DIFFERENCE IN EUROPEAN/U.S. WORKING HOURS

Stern: You'd have to pull together a lot of data, and hopefully they would tell a pretty convincing and consistent story. You know, there are some economists in the United States, including some who work for me, who argue that when they look at the difference between what goes on, on both sides of the Atlantic, one of the things that stands out is that American workers work many more hours annually than European workers, and Minneapolis Fed economists attribute that to higher taxes on earned income here in Europe and to some of the laws that make labor markets here relatively inflexible. Would you agree with that assessment?

Trichet: Yes, very much indeed. I think you have two alternative explanations. One is that it is the free decision of people of Europe to make a very different arbitrage in comparison with the United States—fewer leisure days and much more hours worked in the United States and the contrary in Europe. But when you look concretely at the way decisions are made, the imposition of rules, regulations and taxation systems certainly plays an important role.

I would place more weight on labor laws, government regulations and taxation than on the free decision by the people. Perhaps there is nevertheless some cultural divide that might be part of the explanation.

But on top of the fact that we are working less, it is our view that since 1995 yearly labor productivity progress in Europe is significantly lower than in the United States. Before then it was not the case. On the contrary, from the year 1970 up to 1995, we caught up. There was significantly more labor productivity progress in Europe than in the United States. And the fact is that we didn't catch up as regards the standard of living because at the same time we were gaining a lot in terms of labor productivity progress we started working less and less. So we maintained our standard of living at a level approximately 70 percent of the United States even if in '95 we had attained approximately the U.S. levels of labor productivity.

Since '95 there is a new phenomenon, which is complex, that has been analyzed by the Fed with great care, and a new labor productivity divide is documented. So we are reflecting a lot on that. There are many explanations, including the idea that we are only observing a delay, that we are lagging behind because IT effects take time and that you are ahead of us in that regard. That would be an optimistic perspective. But there might be a lot of other reasons.

I remain of the opinion that when you look at the productive sector, the private, the competitive sector, the same phenomena are at stake in Europe and in the United States, and I take it that there is no reason to think we should be in different universes on both sides of the Atlantic. The technology available is the same. And after a sufficient period of time you might expect the productivity indexes to be approximately at the same level. Still, a difference must probably be underlined between the manufacturing sector and the service sector: The degree of competition in the service sector in Europe remains insufficient, and we call for achieving the single market more resolutely in this sector.

But where there is undoubtedly a big difference is in the public sector, and clearly the level of public spending is much higher in Europe than in the United States. There you cannot expect much labor productivity increase and its contribution to growth and prosperity to be as strong as in the competitive sector. So there we have a handicap, which is undoubtedly part of our problem. And so, we are back to the Lisbon agenda, and all the necessary structural reforms.

Stern: It's an interesting topic. In the United States clearly we've benefited from a much more rapid increase in productivity from 1995 to today, but exactly what's been driving that has been very hard to explain. At first people thought, as you know, it was just temporary, that we're going to have a few good years of productivity improvement followed by a return to something more modest. But it's continued. That's obviously good news for our economy, but it's been difficult, at least for me, to explain, because the technology is available worldwide, and while perhaps we've adapted and applied it more rapidly, basically the same technologies are available everywhere.

Trichet: I have a part of my family in the United States; my brother-in-law was a professor in Washington University in St. Louis, Mo. I must confess that when I'm in the United States it seems to me that the public at large has assimilated IT much more than in Europe. So there perhaps is a slight cultural advance, and it is likely that this dissemination of IT progress in the full body of the economy is much easier in a universe where culturally everybody is prepared. If that's true, of course, it will be a question of time, as you said, before the impact of the IT revolution spreads in Europe.

I'm also struck by the fact that in the United States you have had a very important degree of productivity progress in retail business, for instance, where I must confess we are in Europe at very different levels on a country-to-country basis. We have some economies which are lagging behind with old-fashioned retail businesses. We have others that are very advanced.

MAKING POLICY IN AN ENLARGED ECB

Stern: You were talking earlier about policymaking in the central bank, how it's been what we would call collegial and how you've been able to get all 12 or 18 people to come along pretty well. But as the euro area expands I would think that might make that a bigger challenge.

Trichet: Well, we have been reflecting on that very important question. We were asked by the Nice Treaty to make a proposal for decision making in the enlarged format of the euro area, and it has been a long, long, long discussion, but we were able to come to unanimity. We have imagined a system which is more or less close to yours; namely, that when we are over and above a certain number of participants, we would begin to have a rotation system. We will start implementing a rotation of the voting members of the Governing Council, the decision-making body for monetary policy, so that there are no more than 21 voting members, whatever the number of economies of the euro area will be.

Everything is prepared and it has been adopted by Europe. We were very happy about that because it was not easy to find a consensus, but the solution presented by the Governing Council of the ECB appeared to be the only working one in the eyes of all. So I believe we will maintain a good decision-making process and this exceptional level of credibility which is essential for us. Because again, everything relies upon our own present credibility, our future credibility. We don't have a long track record that you can ask market participants to look at. We must be constantly credible and time consistent. And this new system which is now well known the world over has been welcomed by observers and market participants.

In the future, in a substantially enlarged euro area, we will maintain the number of voting members at 21. But the other members will attend the meeting also, though without a vote, so that everybody—being physically there—will be able to understand fully what has happened, understand fully the reasoning behind our decisions and be able to deliver to his or her own constituency, country, economy and also, I would say, to all responsible persons and opinion leaders in his or her country whether they are economic or union or political leaders, all that is necessary so that they can understand what we're doing. I expect that it will function well.

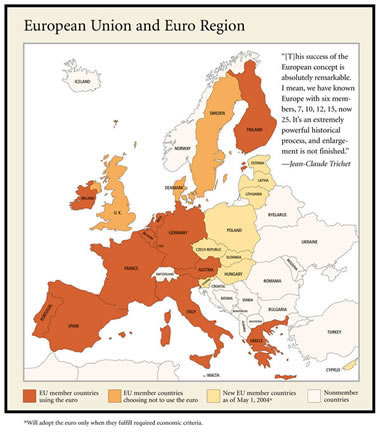

That being said, of course, this success of the European concept is absolutely remarkable. I mean, we have known Europe with six members, seven, 10, 12, 15, now 25. It's an extremely powerful historical process, and enlargement is not finished.

We have "cultural days" at the ECB which this year were devoted to Poland, so we had the celebration with friends from the 25 member countries and the Polish governor. We had a panel of discussion on enlargement. It was a rather enthusiastic discussion, one of us calling for an even bolder enlargement.

Stern: Did that mean he wants Turkey to join?

Trichet: He wanted very much Ukraine to be part of the European Union! It is clear that my colleagues and I, and the staff here, we have the sentiment to be part of history in the making, to participate in the historical process. That process is, of course, very challenging, very demanding and in some respects quite unpredictable. Where will we stop the concept of the European Union? That is to be decided by the people and by history.

Stern: I agree with your description and I agree that it's remarkable. I have to say that coming from the other side of the Atlantic, it's hard for me to appreciate the challenge. Because while I think it's fair to say that many of us have had a long-term interest in the difficulties in bringing together heretofore independent states, different cultures, different languages, and so on and so forth, it is something that is very hard for an outside observer to truly understand and appreciate.

Trichet: Yes, you have to live that from the interior. I must confess I saw this myself because I was very frequently on both sides of the Atlantic during the run-up to the euro, so I saw the difficulty the New York markets had in understanding that we really would create the euro. At the end of 1997 you had still around 80 percent of New York market participants absolutely convinced that it would not be done, when we knew ourselves that there was a 99 percent probability that it would be done. So it was there, particularly striking, the cultural difficulty in understanding what was happening on each side of the Atlantic.

BASEL II

Stern: Let me ask you a banking question or two relating to the Basel II capital standards. I gather those are pretty well agreed to now and will go into effect in a few years. Are bankers and bank regulators and supervisors in Europe comfortable with all of that now? Or, on the other hand, are there still a lot of concerns about how that may play out, what the effects will be?

Trichet: I would say that now we have a very, very good understanding of the consensus which has been attained after, I would say, profound and very important discussions in the Basel committee, and at the level also of the enlarged G10 governors plus heads of surveillance authorities that we have organized. I happen to have the weighty responsibility of being chairman of the G10 governors, and we had a meeting with this enlarged body, with the heads of FSAs [financial services authorities], the heads of independent commissions and the governors.

As regards the organization of relations between central banks and banking surveillance authorities, I would say that our understanding in the Eurosystem, in the euro area, is close to that in the United States. The Eurosystem has made public what it thinks is the best concept, which puts us in the same intellectual school as the Federal Reserve—namely, that we think that there are benefits from having a close relationship between banking surveillance and the central bank.

So again, to respond clearly to your question, I would say, in Europe, yes, there is the view that we came to a full understanding and a good consensus after deep discussions on both sides of the Atlantic and in the rest of the world. Of course, we now have to implement it, which is not necessarily easy, but I expect that it will go reasonably smoothly.

I must say that we are very grateful to former New York Fed President Bill McDonough for having started the process; he was a formidable chairman of the Basel Committee. We are also grateful to Fed Vice Chairman Roger Ferguson for having done a great deal of work in bringing about good understanding. And again it's very important that we cooperate as closely as possible. I will take advantage of this opportunity to say that we have a very good relationship with the Federal Reserve, as you well know, and we prize this relationship very much.

CHINA AND INDIA

Stern: That's always good to hear. The sentiment is mutual, I assure you.

One final question, if I may. In the United States today when you start talking about the economy, sooner or later the talk will turn to China and perhaps to India because, well, scale matters. There are so many people there; those economies are clearly starting to do better, which provides some real opportunities and real benefits but also can make for some difficult adjustments. Are they on the radar screen here in Europe as well, or are Europeans less concerned about China and India than Americans?

Trichet: No, I would say these issues are very much on our minds, very much so. We certainly have the sentiment that the world is changing very rapidly. We feel, exactly as do people in the United States, the extraordinarily rapid development of the emerging world in general—China, India and also the full body of emerging Asia, which is very impressive. But I would not forget Latin America, where Mexico and Brazil, in particular, are more and more present on the international trade scene.

I have the view, if I may, that it is key to have better participation of China, India and a number of other emerging economies in our own discussions. And we do, at the level of central banks, in the global economy meeting that we hold every two months in Basel. At those meetings we have friends from these countries and they bring a lot. We cannot understand the global economy without fully recognizing their influence, their participation and, of course, the challenges and issues that are associated.

The fact that China and India have at present their own specializations, that one is more specialized in manufacturing goods and the other is more inclined towards services and IT services is also very striking, and I would say that we have—and it seems to me that it's more or less the same in the United States—to explain to the public, to our fellow citizens, why the global economy, why globalization, is a positive-sum game.

Stern: That can be difficult to explain in the United States.

Trichet: Yes, it's also difficult in Europe, undoubtedly. The economies that have special difficulty to adapt, of course, are not looking much at the opportunities side of the coin when such rapid transformation is at stake, but only at the demanding call for more rapid adaptation and change, and structural changes. So of course we have the usual debate on the rapidity of the structural transformations.

But I have to say—having myself been associated for a very long period of time with this international debate, having known the period of time where you had a North and a South with a great conceptual divide, having known the time when you had an East and a West with an extreme philosophical and political divide—it is remarkable to be in a world where we all agree on a large number of market economy principles, where there is no such philosophical divide, and where we are observing the progressive realization of the ideals of the Bretton Woods institutions. I mean, we created the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to strive for a more prosperous world in which not only the industrialized countries but also the Third World, we didn't say at the time the "emerging countrieS" but we said the "developing countries," including the least developed, would grow, would develop and, progressively, catch up with the industrialized world.

Amongst the least developed you had precisely China and India, which are now growing at a very fast pace! So, in a historical perspective, it is a success which is tremendous, and we have a tendency to forget this formidable success and concentrate on the new problems associated with it. I think that it is perfectly understandable, and we have to face resolutely the new challenges coming from a very rapidly changing world. But let us not forget that what we are observing is exactly what the founding fathers of the IMF and the World Bank would have loved to imagine one day.

Stern: Right, right. I think because economists and central bankers get paid to worry it's refreshing to hear you expound on the positive aspects of all this. I agree with you. I think in the long run this is all to the good. Well, thank you very much. I really appreciate the thoughtful responses you've given to these questions.

Trichet: It was a great pleasure.

This interview was conducted Sept. 17, 2004, in Frankfurt, Germany.

More About Jean-Claude TrichetProfessional Positions

DecorationsFrance: Officier de l'Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur France: Officier de l'Ordre national du Mérite Foreign Honors: Commander of the National Orders of Merit in Austria, Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Ivory Coast, Ecuador and Yugoslavia AwardsInternational prize "Pico della Mirandola" (2002) "Zerilli Marimo," Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques (1999) Policymaker of the year, The International Economy magazine (1991) EducationGraduate of the École nationale d'administration (1969-71) Graduate of the Institut d'études politiques de Paris Bachelor's degree in economics, University of Paris Graduate of the École nationale supérieure des Mines de Nancy |