Call it Plan B for Team USA.

Widely considered the captain for global free trade, the United States has taken a significant tactical shift in its trade policy.

With multilateral negotiations for global free trade currently at a standstill—punctuated by the collapse of trade negotiations in Cancun, Mexico, last year—the United States and most other countries have changed their focus. Rather than continuing to swing for the fences of multilateral free trade, they are hitting singles by entering into so-called regional trade agreements* with individual countries.

Regional trade agreements (RTAs) have been around for decades, but they have become the main trade game for most governments. The rationale is straightforward: There is a clear theoretical and empirical link between trade openness and economic growth. So if trade openness cannot be won multilaterally among members of the World Trade Organization (currently numbering almost 150 countries), then do so with baby-step agreements among individual WTO members.

But will regional trade agreements get us to the global holy grail of free trade? Are RTAs, as framed by Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati, building blocks or stumbling blocks to global free trade?

Surprisingly, there's no widely accepted answer to that fundamental question. Despite their strong consensus on the virtues of free trade, economists diverge widely—and vehemently—on the utility (or destructiveness) of RTAs as a means of achieving global free trade. Workable, believable, supportable theory abounds on both sides—as do refutations of virtually all arguments posited to date.

What's lacking is strong empirical evidence of who's right and who's wrong—clear demonstrations of the welfare gains (or harm) to member and nonmember countries of RTAs. Such examples are hard to come by. As our understanding of the factors of trade and growth becomes more sophisticated, so too does our recognition of the innumerable intersecting and confounding aspects that influence trade and trade policy—a phenomenon that Bhagwati aptly described as a "spaghetti bowl" almost a decade ago.

First, a word from our RTA sponsor, Mr. Article XXIV

The modern version of RTAs came in 1947 with the implementation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. GATT was designed to encourage free trade on a multilateral basis (that is, among all countries) by regulating and reducing tariffs on traded goods and by providing a common mechanism for resolving trade disputes. Built on principles of nondiscrimination (for all or for none) and reciprocity (if received, then given), GATT and its successor, the World Trade Organization, were designed to move all countries toward freer trade—slowly, if necessary, but relatively in step with each other—through steady liberalization of most-favored nation policies, or the tariffs and nontariff barriers that countries often impose on imports.

Embedded in GATT was a provision, known to trade wonks as Article XXIV, that allowed for the establishment of free-trade areas and customs unions to facilitate freer trade among countries while multilateral negotiations trudged along.

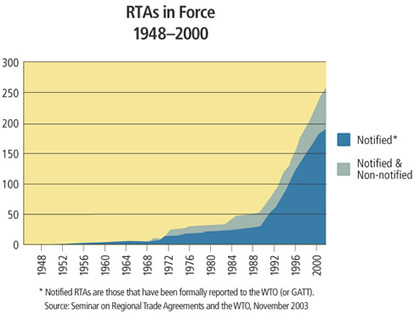

What started as a trickle of RTAs among individual countries has turned into a torrent today (see chart). According to a November 2003 summary report from the WTO Secretariat, the push in trade agreements "which gathered pace in the 1990s continues unabated." As of October 2003, all but one of the WTO members were participating in or already active in an RTA (Mongolia is the exception).

Indeed, the WTO's launch of the Doha Development Agenda in November 2001—set in place expressly to move the world closer to multilateral trade—was followed by "one of the most prolific" periods of new RTAs, according to the WTO report. In the two years following the Doha launch, the WTO was notified of some 33 bilateral and other trade agreements. In 2003, 12 RTAs were signed, negotiations were started on another nine, and 13 more were proposed.

The WTO has identified three overarching trends in trade agreements: More latecomers are trying to catch up to the RTA bus, countries are seeking more partners far afield, and numerous continental megablocs are in the works. In the last five years, according to the WTO, many nations beholden to most-favored nation liberalization—China, Hong Kong, Australia, Japan—"have added the RTA card to their trade policy repertoire and appear to be making up for lost time by energetically seeking RTA partners."

In the Western Hemisphere, the WTO notes, "one of the other most significant developments" is the aggressive shift by the United States in favor of RTAs. The United States signed its first modern-day RTA in 1985 with Israel and added another with Canada in 1988, which later included Mexico and evolved into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994.

But the United States has been particularly busy in the last few years, signing separate RTAs with Jordan, Chile, Singapore and Australia. Earlier this year, it made agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic in the creation of CAFTA (Central American Free Trade Agreement). A number of these agreements must still be approved by Congress.

The United States is looking into a handful of other agreements, according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, either proposing or starting negotiations with Panama, Morocco and Bahrain, as well as plurilateral (or multicountry) agreements with four Andean nations (Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador) and five countries in southern Africa (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland). In May of last year, President Bush announced a Middle East initiative to promote trade expansion and economic reforms in North Africa and the Middle East, with the hope that it will lead to a Middle East Free Trade Area within a decade.

U.S. policy toward RTAs has undergone "a radical shift," writes Richard Feinberg, a political economist at the University of California, San Diego, in World Economy last year. "The nation that for decades was the foremost advocate of global multilateralism, that for decades was skeptical and sometimes hostile toward regional arrangements as being discriminatory, less efficient and potentially divisive, has now joined the rush toward bilateral and regional trading arrangements."

U.S. officials generally take a better-than-nothing view on the push for RTAs. U.S. Trade Representative Robert Zoellick has said repeatedly that the United States favors a policy of "competition in liberalization," believing that countries will compete with each other to sign pacts with trade partners. Doing so keeps the ball rolling toward more globally liberalized free trade.

The 2003 WTO Secretariat report acknowledges that RTAs "may be the only option if there is resistance to liberalization at the multilateral level." Countries are looking to find larger markets for their producers, "which might be easier to engineer at the regional or bilateral level, particularly in the absence of a willingness among WTO members to liberalize further on a multilateral basis. In this sense, the setback of negotiations at Cancun apparently precipitated the forging of more regional partnerships."

The trillion-dollar trade question

But will RTAs involving two, three or even 20 countries get the world to the same free-trade destination as a multilateral approach? That is a burning question among economists, who agree widely on the general benefits of free trade. But as far as choosing the path—big multilateral steps or smaller RTA steps—to that global nirvana, there is widespread, even hostile, disagreement.

The issue has seen considerable research to date. While it has added to our understanding of trade and its many resident economic and political theories and issues, the weight of research evidence does not greatly favor either side yet.

Start at the beginning of the argument: It is widely agreed (among economists, at least) that multilateral free trade is the best choice for countries, both individually and collectively. Given slow progress on this front, the next-best option is RTAs, at least in the eyes of many.

The theoretical arm-wrestling over the welfare effects of RTAs traces back to international trade theorist Jacob Viner, who in 1950 cast the debate in a simple question: Do RTAs create new trade or do they merely divert existing trade from one nation to another? When they generate new trade, they enhance wealth and are therefore good. But RTAs have also been shown to divert trade by improving the terms of trade between trading partners vis-á-vis nonmembers. In such cases, they can reduce global welfare and are therefore bad, at least on the whole.

For example, suppose China can make a T-shirt for $4, Swaziland can make it for $5, and garment exports from both countries face a U.S. import tariff of $2. All other things equal, U.S. retailers will buy T-shirts from China because they are cheaper. However, suppose that a trade agreement with Swaziland eliminates all tariffs on garments imported into the United States. Now U.S. retailers can (and likely would) buy shirts more cheaply from Swaziland, despite the fact that China is a more efficient producer. Trade has thus been diverted.

Big deal? Yes, at least potentially. Though some parties are better off—U.S. consumers get cheaper T-shirts, and Swaziland producers sell more T-shirts—the net global effect reduces welfare because T-shirt production is diverted away from the more efficient producer, China, and the U.S. government must also forgo tariff revenue from imported T-shirts. More hurtful in the long run, investment capital would likely flow to Swaziland—the higher-cost producer—to capitalize on new profit opportunities. The better trade scenario is multilateral, where U.S. tariffs for imported T-shirts are eliminated for all countries, including China and Swaziland. This allows producers from different countries to compete equally on price, and consumers get the most bang for their T-shirt buck.

There are more than a few studies concluding that RTAs divert trade. Howard Hall of the St. Louis Fed reports in a 2003 paper on NAFTA that "results for Canadian trade are consistent with trade diversion." Also last year, Kyoji Fukao, Toshihiro Okubo and Robert Stern published a study in the North American Journal of Economics and Finance that found evidence of NAFTA trade diversion, mainly for U.S. imports of textiles and apparel. In 2001, economists Isidro Soloaga and L. Alan Winters looked at trade activity from 1980 to 1996 and found "convincing evidence of trade diversion" from RTAs in the European Union.

The WTO Secretariat report offers something of a shoulder shrug on the topic. Over 200 RTAs are in effect today, and "[i]t is notoriously difficult to assess the trade creation and diversion effects for a single RTA ... the empirical evidence on the subject remains ambiguous."

Meredith Crowley, an economist at the Chicago Fed, writes in the December 2003 issue of Economic Perspectives, "Today, the question of whether regional trade agreements are trade creating or trade diverting remains unsolved. ... Because economies and trade are always growing, it is hard to construct a counterfactual estimate of how much trade would have grown among RTA members if these countries had not formed an RTA."

On the whole, however, an RTA can be defended on the fact that it expands net trade even if the RTA involves just two countries. Some trade diversion might occur, but no RTA has ever been shown to reduce overall trade. What's more, trade diversion decreases as an RTA grows in membership, á la CAFTA or the European Union.

A 2002 review of farm policy reforms by economists Mary Burfisher, Sherman Robinson and Karen Thierfelder is representative in its findings that RTAs create net trade and enhance welfare. The authors state that empirical work in the narrow framework of trade creation or diversion indicates that RTAs "are generally good for their members, that they are not seriously detrimental to nonmembers, and that global liberalization is always better. With few exceptions, there is no convincing empirical evidence that trade diversion dominates in the RTAs considered."

Won't you be my trade neighbor?

Economists have come to realize that the Viner framework of trade creation or distortion, though useful, is too simple, particularly because RTAs are themselves becoming more complex. After World War II, most trade agreements were fairly shallow and dealt with import tariffs. Today, agreements also regularly try to achieve "deep integration," eliminating or harmonizing nontariff barriers that impede economic activity between countries. These nontariff barriers can include areas like investment and competition, environment and labor standards, fiscal and monetary policy, and even administrative idiosyncrasies.

The WTO Secretariat report points out that deep integration goes beyond the immediate vision of multilateral negotiations. As such, RTAs can act as something of a scout team to help educate the multilateral process. "In these and other ways, many of the new [RTAs] are anticipating the evolution of the GATT/WTO system."

Deep integration also offers multiple additional lines of inquiry in determining the net welfare effect of RTAs. In a December 2003 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Philippa Dee and Jyothi Gali find that smaller trade agreements can positively influence technology and knowledge transfer, productivity, capital investment flows, and environmental and other regulations. More to the point, the welfare effect of these nontrade items outstripped the welfare benefits of traded goods (though possibly, in part, because barriers of traded goods have already been lowered significantly in many countries).

Most often, deep integration takes place on a regional basis with neighboring countries. Historically, trade took place between neighboring countries because of transportation and distance advantages, but also because those countries were more likely to share common traits—language, cultural familiarity—with neighbors than with far-flung countries.

As countries became familiar and comfortable with RTAs, they expanded them in terms of scope and geography, putting multiple regional countries under the same RTA (that is, a plurilateral agreement). The European Union is the granddaddy example in tenure, scope and depth of integration. With NAFTA, CAFTA and possibly an RTA with four South American countries in the near future, the United States is hoping to ultimately fashion a trading bloc—Free Trade Area of the Americas—that would span the entire Western Hemisphere. It's an idea that has been under negotiations among some 34 countries for a decade now.

The expectation is that these regional blocs will evolve into multilateral free-trade arrangements through something of a virtuous incentive cycle. The formation of RTAs—which lower trade barriers between two or more countries—also theoretically removes barriers for multilateral trade liberalization, which in turn makes it easier for still more RTAs.

But again—sorry to interrupt the celebration—numerous economists suggest that this bloc party will likely stop short of the ultimate goal of global free trade because not everyone will be invited. A 2000 study of RTAs and the WTO by Jo-Ann Crawford and Sam Laird of the WTO notes that emerging blocs all but ignore the least-developed countries, like those of south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. They write that "there is no reason to expect a simple answer to whether regionalism encourages or discourages the evolution towards globally freer trade. Similarly, the jury is still out on whether the emerging mega-blocs of RTAs will facilitate or frustrate the making of multilateral agreements."

Soamiely Andriamananjara, an economist with the U.S. International Trade Commission, argues that regional blocs theoretically can be stepping stones to multilateral free trade because membership benefits give nonmembers (especially small economies) an incentive to seek inclusion into regionwide RTAs. Those left behind are hurt even further, offering nonmembers added incentive to join. Nonetheless, given current political and other circumstances, Andriamananjara writes in a 2000 paper that "the expansion of the bloc is not likely to yield global free trade" because admission into the trade bloc is determined by members, whose benefits are diluted as the trade bloc gets larger.

As such, regional RTA blocs are stepping stones to free trade when membership is open, and stumbling blocks when membership is closed or selective. Smaller or lesser-developed countries are attracted by the notion of having preferentially open markets—open to me, but closed to you—because they provide an advantageous trade position vis-à-vis their competitors. Such countries might well resist efforts toward multilateral trade.

In remarks prepared for a trade forum last year, Andriamananjara points out, "It is perfectly conceivable that countries like Mexico or Chile, which already enjoy privileged access to the two largest markets in the world (the United States and the European Union), lose interest in or even resist a multilateral deal that will dilute their preferential access to these markets. In a consensus-based forum like the WTO [where small and large countries have equal voting status], the reluctance of a couple of countries could be much more decisive than another country's strong leadership."

Political jockeying

Political-economy considerations like these point to the second major sticking point with RTAs: entrenchment of vested interests, or those that benefit from the existing trade rules. As RTAs expand in number and geographic reach, they tend not to uproot entrenched interests but rather solidify and multiply them.

A dozen years ago, economist Paul Krugman called international trade negotiations a "peculiarly contorted political economy." Basic economic theory assumes that countries enter into trade agreements to maximize national income and welfare. But Krugman (among others) points out that "the motives of governments as they engage in trade negotiations are by no means adequately described by the idea that they maximize national welfare. ... The apparent conflict between what economists say should be in everyone's best interest and what actually seems to happen politically should be a warning flag—it suggests that whatever is going on in international trade negotiations, it is not welfare maximization."

For each negotiating country, RTAs offer new trade opportunities but also new competitive threats for a finite number of its industries and firms, all of which carry political weight in terms of support or opposition for an RTA. Brown University economist Pravin Krishna notes in a 1998 paper that "producers play a strong role" in RTAs because a country's policy "is driven by the gains or the losses of domestic firms under the different trade arrangements being considered." Producers often prefer to protect existing markets rather than open new ones, in part because some (like the U.S. steel industry) already enjoy preferential arrangements and the benefits that come with them.

That protectionist bent also comes from a historical, mercantilist bias that believes exports are wonderful, but imports are evil, which leads to trade policy that is set "one industry at a time, so general equilibrium is disregarded," according to Krugman. Industries and governments from each negotiating country then agree on an acceptable political equilibrium, an ugly cousin to market equilibrium.

Applied game theory reinforces this point. According to theory developed in 1995 by Gene Grossman and Elhanan Helpman, industry special-interest groups interact with an incumbent government and compete to establish a country's policy preferences. Once established in every country, trade negotiations provide each with enough export winners to gain the necessary support. Consumers—the central beneficiaries of lower-cost imports—are a low priority in the negotiating process, while sensitive sectors like agriculture or other mature industrial sectors often remain protected, even though these sectors offer the biggest potential welfare gains from open trade. That might be the political reality of trade deals, but it further downgrades the economic and social utility of this second-best free-trade option.

Case in point: In February of this year, the United States signed an RTA with Australia. While it lowered tariffs on many items, it continued to protect U.S. sugar even though open sugar trade offered Australia one of its biggest potential benefits, according to that country's Center for International Economics. A Wall Street Journal editorial lamented, "If the Bush Administration won't face down the sugar lobby even for a free-trade friend like Australia, then what chance does the rest of the world have?"

In an op-ed retort, Zoellick, the U.S. trade representative, replied that expectations on both sides were too lofty. "[T]rade negotiators live in the real world, and in the real world objectives must be balanced by sensitivities. ... [B]oth sides start with maximum objectives, but both must settle for slightly less."

By every estimation, such political compromise is the rule with RTAs today. While it does lower some barriers, the expanding web of RTAs also establishes newly vested interests and reinforces existing ones, all of which need to be hurdled in the pursuit of multilateral free trade. Critics have long-noted such political dangers. "In the presence of lobbies, trade diversion is good politics even if it is bad economics," writes L. Alan Winters, an economics professor at the University of Sussex and a Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research in London, in a widely cited 1996 paper. "I find quite convincing the view that multilateral liberalism could stall because producers get most of what they seek from regional arrangements."

Two steps forward, but how many back?

Again, that's not to say there aren't benefits to political negotiating and compromise. Indeed, it's an easy argument: More free trade is better than the same or less free trade. If multilateralism is the best choice, but we can't seem to get there, then the second-best choice (RTAs) becomes the politician's best choice by default. Sure there's trade diversion, but there's also more trade—indeed, usually much more.

But as more countries tread the RTA path to free trade, they are also leaving behind a legacy of entrenched interests that could impede the WTO's multilateral march toward the same goal. Maintaining trade barriers in RTAs for certain domestic industries like sugar is just one example. Possibly a more sinister, festering example concerns so-called rules of origin (ROOs), which are used to determine the original national content of an import coming from a trade partner. These rules are designed to prevent transshipment, or the transfer of goods from one country (a nonmember of an RTA) to an RTA member country for further duty-free (or reduced duty) shipment to a third country that is also an RTA member. Transshipment circumvents the tariffs that would have applied had the first country shipped goods directly to the third country.

While ROOs seem straightforward, even reasonable if one agrees with the need for RTAs, Burfisher, Robinson and Thierfelder say that they "are increasingly recognized as an insidious form of trade protection," in part because high content requirements artificially increase demand for local input, and thus offer a big incentive to divert trade.

In the broader picture, ROOs are part of what critics call "administered protection"—differing tariff levels, implementation schedules, technical standards, customs administration, ROOs and a host of other details-that "allow" trade under the payload of a heavy rulebook and related paperwork. This is what Bhagwati referred to almost a decade ago in his "spaghetti bowl" analogy: RTAs present a multitude of intersecting, overlapping and crisscrossing agreements, each with its own set of unique administrative rules and standards—most of which exist at the request of some industry worried about its competitive trade position. A WTO survey of 215 RTAs covering trade in goods and services in force last year uncovered some 2,300 bilateral preferential relationships.

Such trade complexity can be particularly daunting for small countries and producers in general. As RTAs proliferate, so do myriad rules of origin, at which point customs administration and private sector recordkeeping can become "burdensome," according to a 2003 briefing paper commissioned by the U.S. Agency for International Development. "Anecdotal evidence suggests that for some low-tariff products that are not price-sensitive, the cost of record keeping may outweigh the benefit of favorable tariff treatment." This report and many others have charged that such rules—and ROOs in particular—divert trade rather efficiently, which benefits that diverting country but likely harms others in the process.

And the spaghetti bowl only gets bigger as more RTAs are enacted and trade integration gets deeper, multiplying the conditions on which countries agree to change the terms of trade with each other. As more administrative rules are built up, all of them need to be harmonized or otherwise eliminated for multilateral trade to take place. Given that such administrative rules are often put in place to protect domestic industries from foreign competition, the likelihood of their eventual, wholesale elimination seems no more probable than negotiating the matter on a multilateral level in the first place.

No guard on duty

GATT's Article XXIV was written to ensure that the smaller trade agreements it legalized would align with multilateral goals. But no one really knows whether countries are adhering to the Article's guidelines. Part of the problem is the ambiguity of Article XXIV, which is interpreted differently by the many countries that invoke it.

For example, countries differ on whether "substantially all trade" could refer to the many different product classes or the total volume of traded goods. In either case it allows wiggle room for countries to construct agreements most favorable to their domestic industries. "These divergences of view have made it difficult to conclude the examination of [RTAs] for consistency with WTO rules," according to Crawford and Laird.

The WTO's Committee on Regional Trade Agreements was created to ensure compliance with existing WTO trade rules. But WTO economists Crawford and Laird note, "The CRTA has not been able to resolve many of the 'systemic' issues." They point out, for example, that there "are no explicit WTO disciplines on the use of preferential rules of origin," the absence of which "is a serious shortcoming."

The WTO itself, in the 2003 Secretariat report, says that its rules "have proved through the years to be ill-equipped to deal with the realities of RTAs." The CRTA "has enjoyed little success so far in assessing the consistency of the more than 180 [RTAs] notified to the WTO, due to various political and legal difficulties." Possibly worse, a 2002 report by the U.S. Congressional Research Service notes that WTO members were stacking the agendas of multilateral negotiating meetings with items related to RTAs.

Andriamananjara and others point out that a few seemingly simple steps—like offering open RTA membership (so any country can join if it agrees to lower trade barriers) and uniformly adjusting most-favored nation tariffs applied to nonmembers—would align RTAs with multilateral goals. Unfortunately, virtually no RTAs incorporate these principles. Customs unions—agreements by two or more countries to impose uniform import tariffs (or other trade restrictions) on all other nations—come the closest to such an open and unilateral model, but only about one in 12 trade agreements are of this type.

In remarks prepared for a 2003 trade forum, Andriamananjara offers a pragmatic, if ominous, view on the matter. "On the one hand, difficulty and slow progress in multilateral liberalization seems to have led to the current proliferation of preferential arrangements. On the other hand ... those arrangements themselves may render multilateral liberalization more difficult and less feasible. If those points are both true, the outlook is rather bleak: Choosing the preferential route as the path of least resistance may lead the multilateral trading system into a vicious circle of competitive discrimination—rather than a competitive liberalization."

Model of confusion

In the end, it's difficult to know with certainty whether RTAs are the saving grace of free trade or the devil's own doing.

Theoretical research has not reached consensus because RTAs are notoriously hard to model. Economists know a lot about trade. They know a lot about political economies, rent-seeking behavior, production-factor mobility, technology and knowledge transfer, imperfect competition and foreign direct investment. They also know a lot about game theory. And they can theorize what will happen when you throw them all in the same pot.

But so far, according to a 2003 study commissioned by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, "the bottom line is that economic theory cannot provide clear-cut conclusions, and therefore it is ultimately an empirical issue to determine the net impact" of a given RTA. Problem is, even the empirical evidence is far from unanimous.

The OECD study reviews 40 empirical studies and concludes that the welfare impact of RTAs is positive, but small; trade diversion "can be an issue," particularly for certain countries and business sectors; deep integration generates larger welfare gains than does trade in goods only; the retention of industry preferences can be problematic; and rather than entering RTAs, developing countries would be better served by unilaterally lowering trade barriers and welcoming trade, regardless of reciprocity.

However, these studies "seem to suggest that the quantitative assessments of RTAs are almost as disparate in their conclusions as the theories underlying them." Results, the OECD found, "are highly dependent" on the underlying theoretical model and specific trade scenarios being analyzed.

With squishy evidence regarding the smartest path to free trade, the world's governments have chosen—somewhat by default—a dual-track process for gaining free, open trade: infrequent, big, deliberate multilateral steps and lots of little trade-pact steps. Whether they act as complements or substitutes will continue to be hotly debated. But today, the RTA model appears to be the only one the world can stomach. Clearly, the world wants free trade, but its individual members don't trust the other guy to handle it properly.

So while economists argue with (or in many cases, past) each other about the pros and cons of these agreements, the RTA train has already left the trade station. In that sense, RTAs have won the day because they are clearly the strategy of choice, given their rising numbers as well as the current political breakdown of multilateral talks.

That doesn't mean RTAs have won the trade war. The world is still a substantial distance from the ultimate goal of multilateral free trade, and RTAs are now under the microscope. Time and a good rearview mirror may be the most useful tools we have in determining whether an incremental RTA strategy is a practical path to a multilateral trade goal.

*Discussions of trade agreements often use "regional," "free" and "preferential" somewhat interchangeably, although each is technically different from the others. This article uses the term "regional trade agreement," or RTA, referring to trade agreements between two or more countries.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.