"Mortgage rates hit record lows—refinance today!"

"First-time home buyer? You can't afford to miss out on this historic buying opportunity!"

Does this sound familiar? It should if you listen to the radio, watch TV, read e-mail or sift through your snail mail. While the urgency of marketers may be somewhat overdone, underneath the promotional hyperbole lies some serious mortgage activity.

At both district and national levels, low interest rates in the past three years helped fuel a surge in the number of mortgage originations, that is, new-home purchases and refinancing of current mortgages. Though total mortgage originations grew throughout the district, a closer look at individual metro regions reveals very discernible differences in the strength and composition of mortgage activity.

There's no place like home

Between May 2000 and June 2003, the average rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage fell from a high of 8.66 percent in May 2000 to a low of almost 5 percent in June 2003, according to data from the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) (see chart below). Rates have since bounced back up—hovering around 6.1 percent as of July 2004—but are still low in historical terms.

The general effect of the rate drop could not be more obvious. (Data on mortgage activity are not available at the state level but are available for metropolitan statistical areas through 2002 from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), which requires mortgage lenders to report activity. Data for 2003 are scheduled for release in August, after deadlines for this issue.)

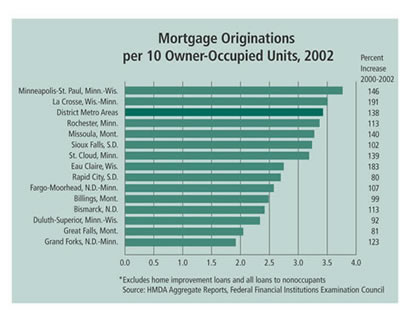

From 2000 to 2002, annual mortgage activity in 14 district metro areas skyrocketed 138 percent from about 153,600 (which include, conventional, government-sponsored and refinance loans to occupants) to 366,000. The dollar value of those originations more than tripled from $16.9 billion to about $52.5 billion. The growth rate among district metros also outpaced the national average in both quantity and value.

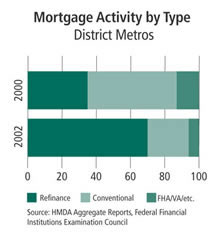

While growth occurred in all mortgage segments, a flood of refinancings drove the overall trend. In 2000, conventional mortgages comprised five of 10 originations in the district's metro areas. Refinancing accounted for less than four of 10, while government-sponsored home loan programs (including those from the Veterans Administration, Federal Housing Administration and others) made up about one of 10. By 2002, refinancings made up seven of 10 originations (see chart).

Home sweet home

Everyone knows that low interest rates are better than high interest rates (well, for the consumer at least). But the last three years have offered unprecedented purchasing power and cash savings to homeowners, whether they are buying a new home or refinancing an existing mortgage.

According to traditional guidelines, someone with a $40,000 income and a down payment of 10 percent could afford a $113,000 house at an interest rate of 7.5 percent. But the same income could buy a $145,000 house if the interest rate dropped to 5 percent. Put another way, the monthly principal and interest payment for that $113,000 house ($100,000 loan with 10 percent down) for 30 years goes from $700 at 7.5 percent to $537 at 5 percent.

Such financial incentives encourage potential first-time home buyers to make the leap and existing homeowners to upgrade to a larger home or refinance an existing mortgage. Together, these groups increase housing demand—and with it, housing prices—in something of a self-reinforcing cycle, according to Wade Abed, president of the Minnesota Association of Mortgage Bankers Inc. and CEO of Northwest Mortgage Co.

"In a market with falling [interest] rates, current homeowners may have a greater incentive to sell their homes and purchase new ones because rising values give them increased buying power. As a result, homeowners are better able to upgrade their house or buy a second home," Abed said.

Still, the new-home market generally sees less volatility even when rates plunge. The MBA's new-home purchase index (which tracks purchases of newly built and existing homes) shows a fairly slow, steady increase from 1990 to 2004. While lower interest rates help—evident in the strong growth of new-home purchases the last three years—they are likely only one of several drivers pushing this market. For starters, a home purchase is a long-term decision for a household, one that might not always coincide with favorable interest rates.

Second, home purchases are also influenced by broader trends in population and income: As population grew in the 1990s, so did the new-home market; solid income gains since 1990 also contributed significantly to people's ability to purchase a new home. Third, first-time home-buyer programs became more aggressive—like offering lower and even no-down payment options—making it easier still to purchase. These factors helped purchase activity trundle steadily upwards.

Going up

The refinancing market—refi, in industry lingo—is a different story. Compared to the steady purchase trends, refi trends are a manic thrill ride. That's because refinancings exhibit an amplified inverse relationship with fluctuating interest rates: While high rates essentially mothball the refi market, falling rates dramatically accelerate refi activity (see chart). In 2000, the district's 14 metros had about 56,500 refinancings. That annual figure almost quintupled by 2002 to 258,800 loans totaling $36 billion.

But interest rates have since inched up and the refi market has hit the skids, with the MBA's refi index sliding 86 percent between June 2003 (when interest rates were at their lowest) and June 2004. Over that same period, the MBA's purchase index has actually increased 3 percent.

Said Abed, "You're already seeing refinance activity slow due to increasing rates. Even though you're seeing rates trending upward, you will notice that new purchases and construction are still in great shape, although you will see a decline as rates climb into the mid-7 [percent] range and upward. I'd say we're about a percent and a half from the [purchase] market slowing."

Said Abed, "You're already seeing refinance activity slow due to increasing rates. Even though you're seeing rates trending upward, you will notice that new purchases and construction are still in great shape, although you will see a decline as rates climb into the mid-7 [percent] range and upward. I'd say we're about a percent and a half from the [purchase] market slowing."

One peculiarity of the refi market that may help explain its volatility compared to the new-home market is that individual borrowers often refinance multiple times as interest rates fall. The refi rule of thumb states that when rates fall 1/2 to 5/8 percent age points lower than your current mortgage rate, refinancing could be a wise financial decision—particularly if you plan to stay in the house for an extended period. Given the plunge of over 3 percentage points over the last three years, many homeowners have likely taken a trip down the refi road multiple times.

In Montana, refi numbers "were huge," according to Maureen Rude, director of Fannie Mae's Montana Partnership Office. The office purchased about 26,000 loans on the secondary market in 2003, and 78 percent were refinancings. "I would venture to say that some people are counted in there more than once. Personally, I've refinanced three times in the last four years. I imagine there are a lot of people who did the same thing."

Regional variety

Though mortgage activity has been strong throughout the district, a look beneath the hood reveals strikingly different levels of origination activity (purchase and refi) in district metros. These variations shed additional light on some of the drivers of local housing markets.

If one looks at 2002 activity in terms of owner-occupied housing in district metro areas, one of three such units experienced some sort of mortgage activity in 2002. But regional differences were considerable: 3.8 originations per 10 housing units in Minneapolis-St. Paul compared with 1.9 units in Grand Forks, N.D. (Data on owner-occupied units come from the 2000 census and are the most recent available. This likely inflates activity ratios slightly because it does not count new-home construction from 2000 to 2002. However, given that annual new construction is a small fraction of total owner-occupied housing in a region, and new-home mortgages were a similarly small slice of mortgage activity from 2000 to 2002, the activity rank among district metros likely holds.)

These per-unit figures can vary considerably even in the same state. At a rate of 2.3 mortgage actions per 10 homes, the origination rate in Duluth, Minn., was just 60 percent of the Twin Cities rate. Among several potential reasons for this intrastate variability, population growth probably plays a role. Between 1990 and 2000, the population in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro grew by 17 percent (only Sioux Falls, S.D., and Missoula, Mont.—two of the district's other mortgage heavy hitters—grew at a faster rate). On the other hand, Duluth had the slowest growth rate of all district metros, at 2.3 percent.

"Generally, a growing population leads to increased demand for homes and a higher level of originations. As a local economy continues to grow, build and change, originations tend to move with population growth," said Abed. "On the same note, as population in some areas declines you can see the opposite happen. In Duluth, where a lot of jobs have been lost in the mining industry, you'll see slowing originations as the population grows at a slower rate."

Abed also noted that income and employment mobility can also explain some of the difference in origination activity between metros. In the Twin Cities, a higher level of household income, combined with a more corporate, transitory employment structure, likely leads to greater housing turnover. Contrast that with Duluth, where a lower level of median income and a relatively more stable, industrial employment environment contributes to lower levels of originations—even during a period of falling rates.

However, such relationships or links are not always hard and fast. For example, La Crosse, Wis., is more like Duluth than the Twin Cities in terms of size, industrial makeup, income levels and population growth. Still, La Crosse's origination activity in 2002 rivaled that of the Twin Cities.

District metro areas also differ noticeably in the use of government-sponsored loan programs as a percentage of annual originations. According to HMDA data, these loans comprised roughly 5 percent of all originations in both the nation and the district in 2002. Two Montana metros, Billings and Great Falls, led the way with 16 percent and 13 percent, respectively, while La Crosse came in at a district-low 1 percent. According to Rude, formerly with the Montana Board of Housing, the high rates in Montana metros are not very surprising. She credits the Board—the state's official housing finance agency—for working closely with lenders in Montana communities to offer loans with below-market interest rates. These loans are often combined with down-payment assistance programs to give marginal home buyers the opportunity to realize their homeownership dreams.

"Lenders in both Billings and Great Falls do a fantastic job of working with the Montana Board, and the Board has done an exceptional job of marketing their programs to these communities," Rude said.

As with other mortgage activity, the refi rate in district states and metros exhibits some variability. According to a November 2003 report by SMR Research Corp. of Hackettstown, N.J., the rate of refinance in Minnesota and Wisconsin greatly outpaced other district states (see chart).

Aside from low interest rates, SMR President Stu Feldstein said via e-mail that refi rates are driven by multiple factors, including household debt levels and credit worthiness. People with higher mortgage debt will refinance more often, and as interest rates go down, people with good credit ratings tend to refinance more often than people with credit problems, according to Feldstein. Home type is also a consideration—mobile home dwellers seldom refinance because of lower debt levels, while single-family detached are most likely to refinance. Average income and education levels have also been shown to influence refi tendencies, he noted, and state laws and taxes "can have a huge impact on the refi rate" in particular regions.

Michael Anderson, director of homeownership programs at the North Dakota Housing Finance Agency, pointed out that varying homeownership rates between given communities in the same region may account for some of the refi differences among metros.

"In the state of North Dakota, the telling distinction between a city like Fargo-Moorhead and Bismarck is the homeownership rate. In Fargo-Moorhead, the rate is somewhere around 50 percent, in part because there are three four-year colleges in the area. For the rest of the state, the percentage is closer to 70 percent. So in a city like Fargo, you may find in a given year that a smaller percentage of origination activity will be refinancing," Anderson said.

Betting on the house

Low interest rates have also fueled a hot market in home equity loans, but not all district states were equally active.

The U.S. average for home equity debt per owner-occupied unit is about $6,950, according to 2003 data from SMR on outstanding home equity debt and 2002 census figures on owner occupancy. Minnesota and Wisconsin have higher levels, at $7,708 and $7,476, respectively. Between 2001 and 2003, these two states also registered substantial increases in total home equity debt—27 percent and 39 percent, respectively. At the other extreme, North Dakota's burden is only $1,656, and its total home equity debt load actually decreased from 2001 and 2003. South Dakota, with a relatively low debt load of $2,840 per unit, nonetheless saw total home equity debt rise by 20 percent. Montana lingered in the middle, with a unit average of $3,540 but debt growth of just 5 percent during this period.

Industry analysts say there's a link between the rates of owner occupancy, outstanding mortgages and home equity loans, and district states offer a useful anecdote. Wisconsin and particularly Minnesota rank high in owner occupancy, outstanding mortgages and home equity debt; North Dakota ranks low on all measures (see chart).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Summary File 3;

SMR Research Corp.

According to Feldstein, SMR's research models "show that people who have zero mortgage debt are far less likely to get a home equity loan than people who already have some mortgage debt. Those with zero mortgage debt tend to be quite old (average age is over 60), and there's a reason they don't have this debt—they don't want it or can't afford it."

North Dakota's Anderson noted that lower median home values may also explain why states like North Dakota register lower levels of home equity debt per unit. But he added that social factors may also shape North Dakota's low figure. "In North Dakota, I think you'll also find that people have more conservative credit habits."